Editor’s note: This is the fourth article in a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. Deep Dive has been chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the 2023 Nonprofit News Awards.

“If man is not to live by bread alone, what is better worth doing well than the planting of trees?” —Frederick Law Olmsted

“To live among the trees without knowing anything about them is much like living in a foreign country among people whose names you do not know and whose language you do not understand.” —Paul Weatherwax

The branches of the giant bur oak spread high over the sidewalk and arch above the lower steps of the Indiana Memorial Union on East Seventh Street just north of Campus River. Even the acorns are huge, the biggest of all North American oaks. The tree is significant: quite possibly the oldest tree on the Indiana University Bloomington campus. Possibly, because until it dies and is cut down so the rings of the trunk can be counted, it’s a bit of a guessing game. Current best guess by IU’s Landscape Coordinator Mike Girvin is somewhere north of 180 years old.

There are a lot of big trees on the IU campus, of more than 12,700 trees that have been GIS plotted and measured for diameter at breast height (DBH) in inches, but the bur oak is special at 58 1/2 DBH. It was there when IU bought the property in 1883.

“It’s now getting a lot of care,” says Girvin. “We’ve done sonic tomography on it, which is basically an MRI of the tree. That tells us how much of the inner wood is solid, if there’s some punky inner wood, and the general interior condition of the tree.” He says the big oak is doing okay and gets nutritional and fungal treatments on a routine basis, and he is looking into bracing some of the larger limbs.

The aging bur oak in front of the Indiana Memorial Union is “getting a lot of care,” says Mike Girvin, landscape coordinator at Indiana University. | Photo by Jeremy Hogan

Aside from the practical and climactic value of trees, such as reducing carbon in the atmosphere, serving as windbreaks, reducing street noise, shading buildings (and thus reducing energy costs), supporting birds and other wildlife, trees have an emotional value to humans. According to a research study by British scholars George MacKerron and Susana Mourato, there is a positive link between well-being and exposure to green or natural environments in daily life.

One of Girvin’s favorite trees on campus is this one he’s standing near, a sassafras tree measuring 41 inches diameter at breast height, by the outdoor pool on East 17th Street near Fee Lane. | Photo by Jeremy Hogan

And the older trees on the IU campus can be quite inspiring. There’s the giant, multi-branching beech tree on East 7th Street by the tennis courts behind Wright Quad. One of Girvin’s favorite trees is a sassafras tree by the outdoor pool on East 17th Street near Fee Lane. “Normally, these trees are spindly and small, but this one is 41 inches in DBH,” he says. “It’s not a state champion by any stretch, but it is a big sassafras.”

Another common, yet uncommon, tree Girvin points out is a tulip poplar behind Read Quad. The tulip poplar is Indiana’s state tree, has a leaf shaped like a tulip, and big, showy flowers in the spring. “It’s close to 60 inches in diameter and has a beautiful root flare and trunk flare,” he says. “I think it’s one of the most striking examples of a tulip.”

Dunn’s Woods does have a number of large trees, too, but it was actually very lightly wooded when IU bought 20 acres of property from Moses Fell Dunn in 1883 for $6,000. The first IU groundskeeper dug up trees from the surrounding countryside and planted them in Dunn’s Woods, which is how it got forested, says Girvin. Some of IU’s trees were dug up and transplanted from IU-owned Griffy Woods, and you can still see big concave impressions at Griffy where the trees were removed. In 2011, a big rain and windstorm took down trees throughout the campus, heavily hitting Dunn’s Woods. The university does not cut down trees there, though, and only moves them if they fall and obstruct a pathway.

Every autumn, some students discover the sweet, soft paw-paw fruit from several trees in the glade beside Bryan House, built in 1923 for IU’s tenth president, William Lowe Bryan, and his wife, Charlotte Lowe Bryan. In spring, the paw-paws produce maroon flowers and sprout up to 12-inch-long oblong leaves that turn yellow in the fall.

Tree maps and inventories

The first tree map for IU was created in 1939 by the Olmsted Brothers, sons of the famous landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, co-designer New York City’s Central Park. Over the years, the university hired landscape architects to envision paths and the expanding campus, says IU historian and professor James Capshew. In 1915, Indianapolis landscape architect George Kessler suggested putting some buildings in Dunn’s Woods. His idea was quickly quashed by President Bryan, as well as others who had come to love the wooded area. Other attempts over the years to build there were similarly stopped, with the exception of the Kirkwood Observatory.

Working on the IU tree survey fostered Hannah Gregory’s love of trees. Here she’s in front of one of the ginkgo trees planted in 1896 outside of Maxwell Hall. | Photo by Jeremy Hogan

In 2016, Sustain IU and Landscape Services commissioned a digital map, which is updated every three years. One of the 2019 tree-monitoring technicians for the project was Hannah Gregory, who is a tree and GIS technician for Landscape Services and an ISA certified arborist. Working on the tree survey fostered Gregory’s love of trees.

“I just fell in love with all the different species and learning how to identify condition issues,” says Gregory, who received her degree from the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA) in 2019. She is now a certified arborist and does urban forestry research for the Environmental Resilience Institute at IU. “The original tree inventory began because landscape services wanted to assess the level of damage from emerald ash borer,” says Gregory. “It had started as an inventory of all the ash trees on campus and then they just expanded it out from there.”

Now, says Girvin, there are about 400 to 500 ash trees left and the university gives treatments as needed for about 130 ash trees, one of which is 70 inches in DBH.

Other notable trees include a pair of ginkgos between Maxwell Hall and Kirkwood Hall that were planted in 1896, says Capshew. The ginkgos are both female trees, but when their fan-shaped leaves are crushed underfoot, they produce a smelly odor. Only the ginkgo female tree leaves create this smell.

(left) Closeup of the leaves of a ginkgo tree. (right) A female ginkgo tree next to Maxwell Hall. | Photos by Jeremy Hogan

Tangible and intangible value of trees

Oblong leaf of the paw-paw | Limestone Post

How much is a tree worth? In strictly carbon-capture and lowered heating-and-cooling costs, the thousands of trees on IU’s campus are worth close to $1,000,000, according to Girvin. But according to a recent higher ed survey of students choosing colleges, the way a campus looks — such as IU’s limestone buildings surrounded by woods — ranks among the top ten reasons for picking a school. Though IU ranks consistently high in that category, it’s hard to put a true dollar value on Bloomington’s wooded campus.

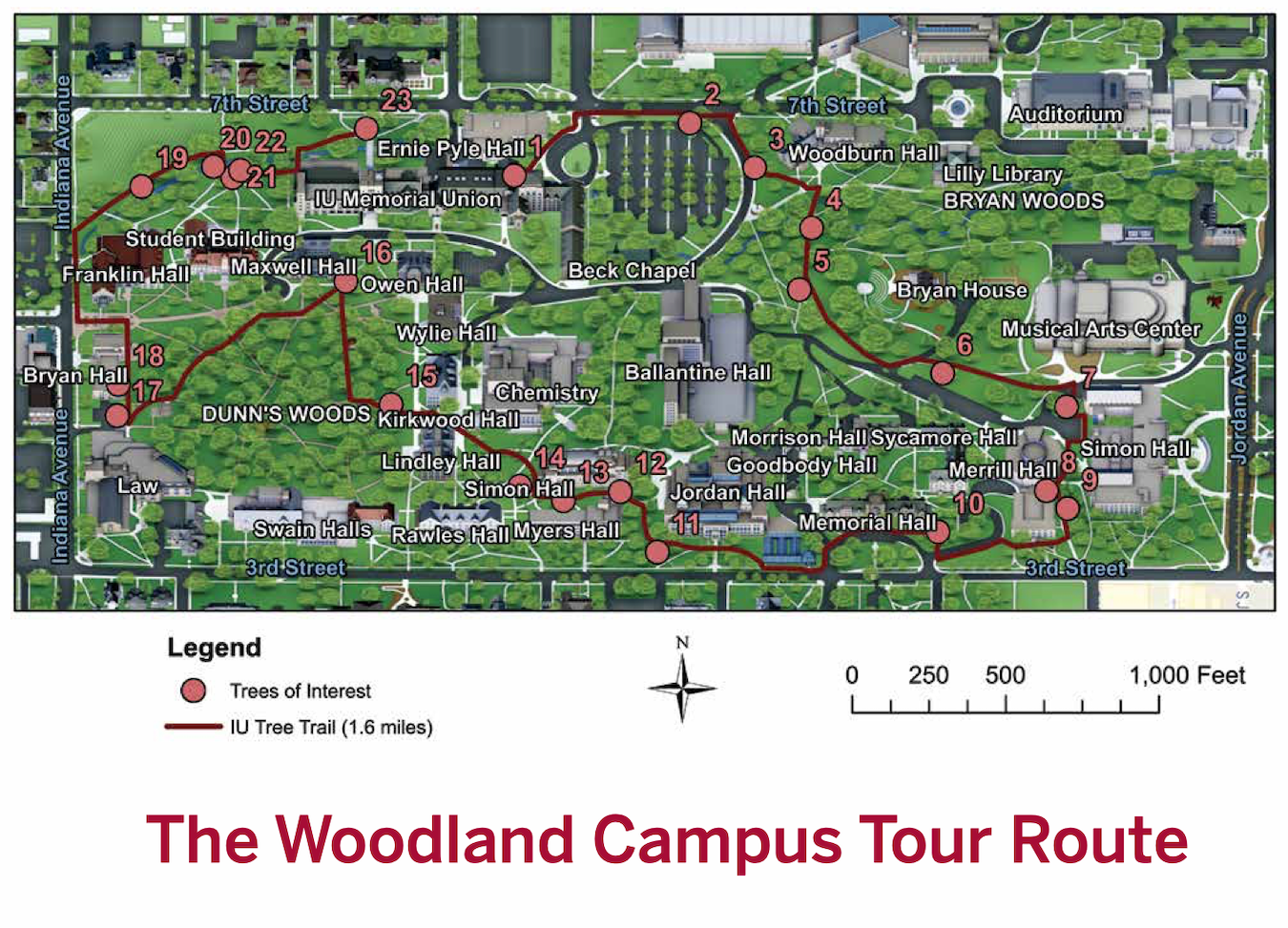

“Trees provide so many ecosystems services like helping shade our homes to decreasing the cost of energy [to heat and cool buildings],” says Sarah Mincey, clinical associate professor in SPEA and a co-author of “The Woodland Campus,” a brochure that includes a historic walking guide to IU trees. She updated and developed the tour and history guide from a 1960 publication by Paul Weatherwax, an IU botanist and faculty member until 1959 and professor emeritus until his death in 1976. “Something that provides so much to us and yet is so unknown to most of us is distressing to me,” Mincey says. “If you don’t know something well, then it’s vulnerable. My motivation is to help people learn about the trees that are around them and the benefits that those trees are providing us.”

As a result, Mincey helped create the GPS-aided walking tour people can access on their phones to identify some of the common species, as well as unique trees, including Mincey’s favorite, a grove of bald cypress trees between Franklin Hall and Dunn Meadow, along the Campus River. Bald cypress grow well in wet areas, and the collection of them here represent to Mincey the university as well — growing and helping each other.

Sarah Mincey, clinical associate professor in the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, co-authored the brochure “The Woodland Campus,” which includes a historic walking guide to IU trees.

Before these measurements and technologies existed, a series of IU leaders encouraged preserving, planting, and maintaining the campus canopy. The first buildings were constructed of limestone at the edge of Dunn’s Woods in what is called the Old Crescent.

Herman B Wells, IU’s 11th president, was a proponent of keeping green spaces throughout the campus. | Photo by Harris & Ewing, 1938, courtesy of IU Archives

Botany professor David Mottier and a committee began planting native trees and shrubs in the early 1900s. Capshew notes that the university registrar at the time, John Cravens, stated in the 1915 Alumni Quarterly that Mottier should be commended.

“As a result, Indiana University has one of the most beautiful campuses in the country,” Cravens wrote. “Its hollows, hills, and level places, primeval forests and recently planted trees, make the campus very attractive. There is a charm about the campus that stays with one through his entire life. When a person has once been on the campus of Indiana University he is forever afterwards enthusiastic about its many entrancing features.”

Today the IU Bloomington campus spreads out over nearly 2,000 acres, much of it purchased during Herman B Wells tenure, from 137 acres in 1937 to 1,700 acres in 1961 when he retired as IU’s 11th president. Wells was a proponent of keeping green spaces throughout the campus as it grew, according to Capshew.

In Paul Weatherwax’s brochure, Wells wrote of the beauty revealed through each season and the need for “breathing space” in the face of increasing urbanization. Paying tribute to earlier conservationists, he states:

To cut a tree unnecessarily has long been an act of treason against our heritage and the loyalty, love, and effort of our predecessors who have preserved it for us.

Older than old growth

While the bur oak is IU’s oldest living tree, there are a few fossilized trees and tree-size plant fossils on campus worth investigating. First is a fossilized stump about 154 inches in circumference (not DBH) brought from a coal mine in Dugger, Indiana, by David Dilcher, professor emeritus of biology and geology, and some IU maintenance workers. Polly Root Sturgeon, education outreach coordinator for Indiana Geological and Water Survey, says it’s of the genus Sigillaria and is approximately 300 million years old.

This fossilized stump northeast of Myers Hall was brought from a coal mine in Dugger, Indiana. It’s of the genus Sigillaria and is approximately 300 million years old. | Photo by Jeremy Hogan

“It used to be located in the grassy area outside of the Jordan Hall greenhouse [now the Biology Building Greenhouse] but was moved to a round, planter-like enclosure northeast of Myers Hall by biology department staff,” Sturgeon says. “It’s my understanding that it was moved when a biology staff member learned about the fossil on one of my campus walking tours, took interest, and got the department to protect it more.” Passersby often take small rocks around the stump and make little rock cairns on top of it.

A collection of fossilized tree trunks that once stood outside Owen Hall are arranged in a plot of land behind the Geology Building, near Luddy Hall. When the fossils were outside Owen, a sign read:

Indiana petrified wood, 300,000,000 years old, Callixyon newberryi, Devonian Age, Clark Co., Ind. An evergreen tree floated into the sea from nearby land buried in the New Albany Black Shale and replaced molecule by molecule by silica from ground water.

From ancient trees around the state to the 300 to 400 new trees planted annually on IU’s Bloomington campus that hopefully will survive the ever-warming temperatures of southern Indiana, the university tree canopy has been maintained and even expanded. It may mean some favorites, such as Norway spruce and other trees better suited to colder temperatures, may not survive.

A collection of fossilized tree trunks are arranged in a plot of land behind the Geology Building, near Luddy Hall. | Photo by Jeremy Hogan

“With these warmer winters and wet springs and all that, we’ve seen a lot more fungal diseases and insect infestations,” Girvin says. “A lot of these trees forty years ago could ward these situations off, but now it creates a lot of climate stress and we see a decline in a lot of our large trees.”

As spring warms up, students unfurl double hammocks and strap them to trees alongside the Campus River or behind Forest Quad, snuggling together. Others walk quietly hand in hand through Dunn’s Woods, a tradition that students of the 1880s and 1890s called practicing “campustry,” or romance in the trees while skipping class.

Girvin is all for the hammocking habit. “Anything that gets them outside and just enjoying the outdoor world of Indiana University is a good thing,” he says.

[Correction: An earlier version of this article stated Hannah Gregory’s title as executive director of CanopyBloomington, but she recently left that staff position and now works as a consultant for the nonprofit.]

(left) Dunn’s Woods, (right) Paw-paw patch next to Bryan House. | Limestone Post

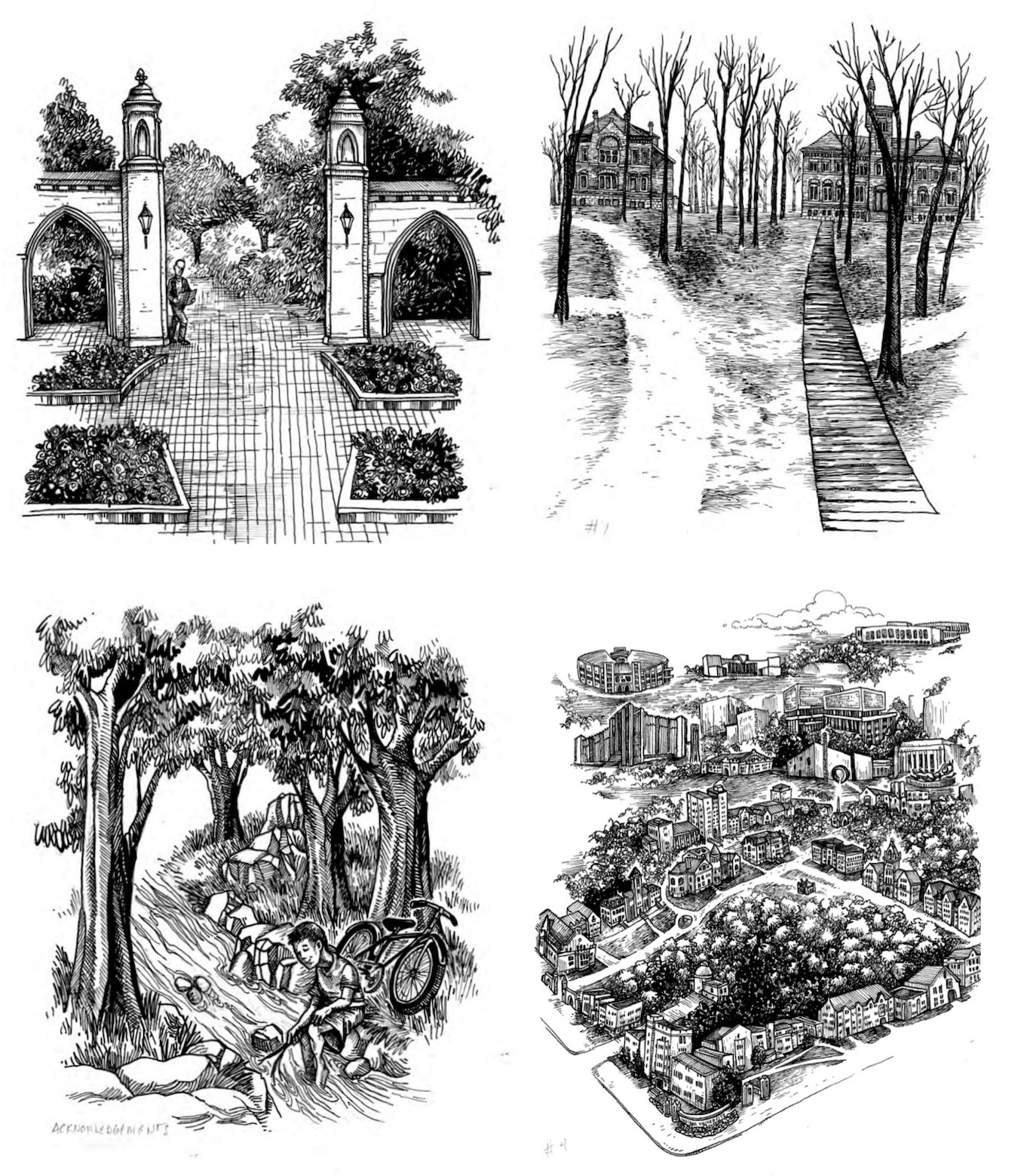

Campus illustrations by Joe Lee

Campus illustrations by Joe Lee for an upcoming book by IU historian and professor James Capshew. (clockwise from top left) Sample Gates, Owen Hall and Wylie Hall (original buildings), Dunn’s Woods and environs, and the Campus River. | Reprinted courtesy of James Capshew

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

Limestone Post article by by Brookelyn Lambright, Karl Templeton, and Brenna Polovina from the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism, published August 1, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

WFHB reports:

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 1), August 7, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 2), August 14, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 3), August 21, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 4), August 28, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, photography by Benedict Jones, published September 24, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

WFHB reports:

- Apprenticeships (Part 1), October 9, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 2), October 16, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 3), October 30, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

Limestone Post article by Haley Miller, published November 26, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

WFHB reports:

- Police and Social Work, January 29, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 2), February 5, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 3), February 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

Limestone Post article by Marjorie Hershey, photos by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian, published January 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

WFHB reports:

- Political Polarization, (Part 1), March 19, 2025

- Political Polarization, (Part 2), March 27, 2025

- Political Polarization, (Part 3), April 2, 2025

Mental Health Issues Are Increasing Dramatically Among Hoosier Youth

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, photography by Benedict Jones, published April 3, 2025

Mental Health Issues Are Increasing Dramatically Among Hoosier Youth

WFHB reports: