[Editor’s note: This is the first article in a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. In this year-long series, every month or so Limestone Post will publish an in-depth article on a consequential community issue, and on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. WFHB will cover related topics during its local news broadcast. This article, by journalist Steve Hinnefeld, is part 1 of 2 on housing in Monroe County.]

[Editor’s note: This is the first article in a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. In this year-long series, every month or so Limestone Post will publish an in-depth article on a consequential community issue, and on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. WFHB will cover related topics during its local news broadcast. This article, by journalist Steve Hinnefeld, is part 1 of 2 on housing in Monroe County.]

Ingrid Davenport loved living in her rented two-bedroom townhouse at the modest Bloomington complex called The Arch. The rent was affordable — $816 a month including utilities — and there was room for her and her two young children. She hoped to stay a long time.

But six months after she moved in, managers posted a notice that tenants would have to vacate. The property had been sold, and the buildings would be razed to make room for new, higher-priced apartments, most of them targeted to Indiana University students.

The Arch, an affordable rental community on the city’s north side, was razed to make room for the construction of these higher-priced student apartments with “resort-style amenities.” | Photo by Jason Vest

“I was heartbroken,” the single mother says. “I was devastated. I was like, what am I going to do?”

It’s a quintessential renting experience in Bloomington, where housing is scarce, expensive, and tilted to the college market. With inflation and growth driving up prices, some tenants are seeing their rents rise dramatically. Many simply can’t find a place, at least not one they can afford.

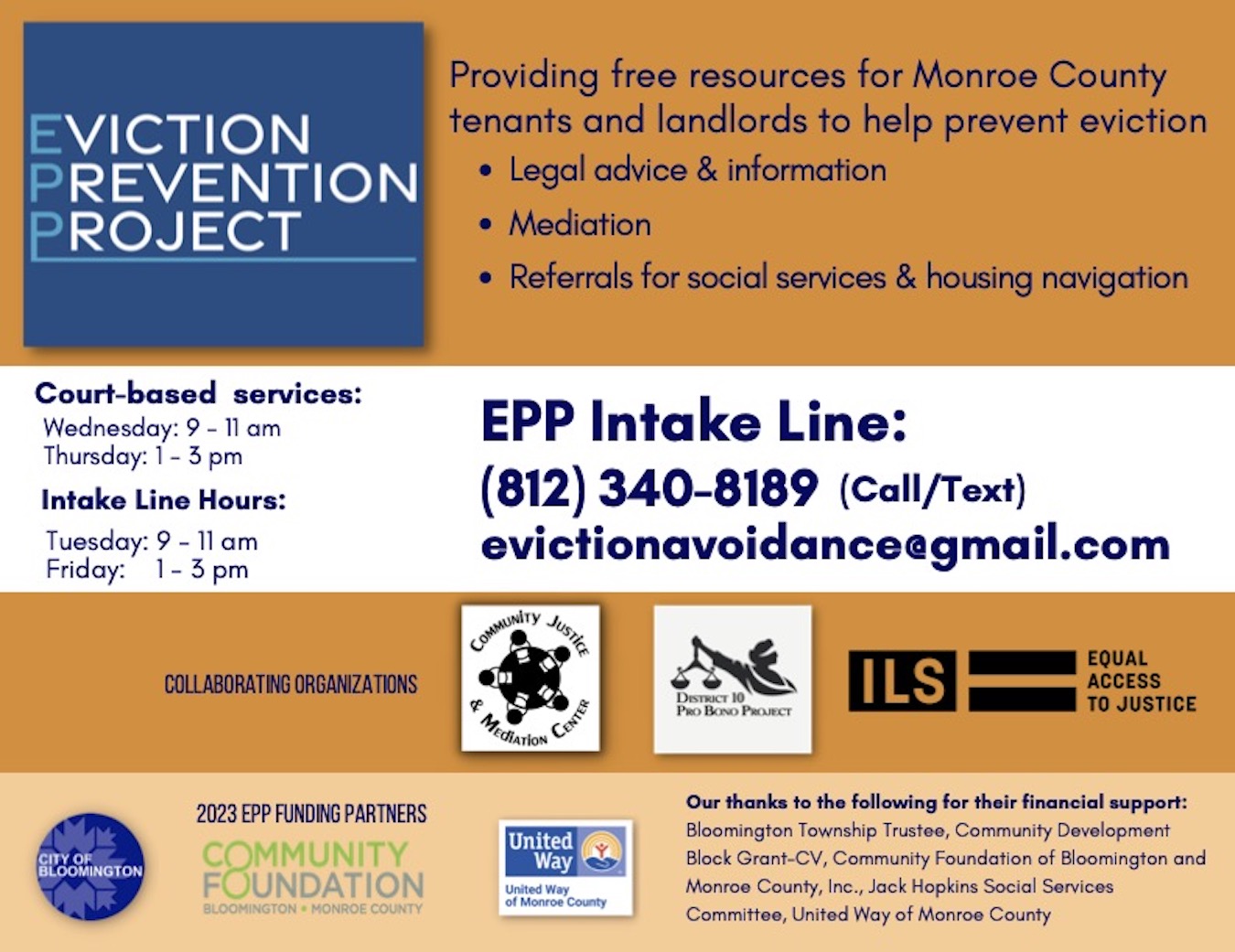

“The places that are getting built, they’re not affordable,” says Tonda Radewan, coordinator of the Eviction Prevention Project in Monroe County. “I talk to people who grew up here, and they can’t live in their hometown because they can’t afford it.”

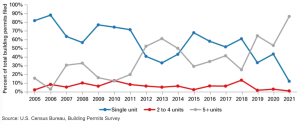

Experts and data agree that Bloomington and Monroe County lack sufficient housing. Building permit records suggest house and apartment construction was slow to recover from the Great Recession. From 2009 to 2019, the county added only 4,715 housing units, according to StatsIndiana. About half of those were single-family homes; fewer were apartments in buildings with five or more units.

“The 2010s just kind of put us behind the eight-ball,” says Carol Rogers, co-director of the Indiana Business Research Center at the Indiana University Kelley School of Business. “There was not as much appetite for building housing after the housing bubble and the recession.”

More recently, there has been a surge in construction of large apartment buildings, not only in Bloomington but across the state, driven by fast-rising rents. But some of those developments have replaced affordable complexes, like The Arch. Most have been targeted to the high end of the market.

A 2022 study by the National Low Income Housing Coalition found that Monroe County had only 16 affordable and available homes for every 100 extremely low-income rental households, the third-worst figure in Indiana. And 88 percent of extremely low-income households spent more than half their income on housing.

Davenport, who works as a server and bartender, says she was given barely two months to vacate. The owners refunded her damage deposit and added about $1,000 for terminating the lease, she says, but that would not cover a deposit and advance rent for a new apartment. And anyway, there was almost nothing on the market at the midpoint of Bloomington’s summer-to-summer leasing season.

Tonda Radewan, in the Charlotte Zietlow Justice Center, is a coordinator of the Eviction Prevention Project in Monroe County. | Limestone Post

She moved her belongings into storage and moved into a house with friends. “But I want my own place, my own place with the kids,” she says. “I look every single day, through Zillow, through Craigslist, on Facebook. And everything is like $1,000 and up.”

And going higher. Courtney Stewart was stunned to learn recently that the monthly rent will increase from $1,200 to $1,600 this summer for the two-bedroom bungalow that she rents in the Prospect Hill neighborhood. The property manager blamed higher property taxes.

“As much as I don’t want to move again, I have to,” Stewart says. “I will not pay that much money to live here. It’s not worth it and I can’t afford it.”

A Bloomington native and a longtime renter who leads an Indiana University asthma education and prevention program, Stewart says she’s had good and bad landlords, but this is the first time she’s been hit with such a rent increase. She says it’s demoralizing.

“I know things change,” she says. “That’s fine, prices rise. But $400 per month in one year? I want to be able to live where I’m from. To do so safely and affordably. I want to have my life here.”

Emily Morgan was hit with a surprise rent increase that’s twice what Stewart faces. In January, she and her partner were told rent for their near southside house would rise from $1,040 to $1,840 a month. The rationale: The owners had formed a limited liability company, so rents were going up.

Emily Morgan, outside of her neighborhood coffee shop, is moving out of Monroe County because the rent on the house she and her partner lived in for ten years on the southside of Bloomington increased by $800, or 77 percent, per month. | Limestone Post

“I was shocked, honestly,” says Morgan, who has lived in the house for about ten years.

She recently left her job as residential program manager at the Bloomington disabilities support nonprofit Stone Belt, where she had worked for 14 years. She’s now a full-time IU student, finishing degrees in art and psychology with hopes of being an art therapist.

“We were no longer a two-income household,” she says. “I’m in school, and money is tighter than it’s ever been in my life.”

Fortunately, she and her partner will be able to rent an apartment that his sister owns in Brown County. It’s affordable, but they will lose the convenience of being close to IU and an easy commute from his job in Bedford. Morgan says the experience sends a message that the rental market is designed for someone else, primarily for college students whose families are paying.

“It just tells me that there’s no room for local people, I guess,” she says. “Unless, of course, you make a bunch of money.”

Struggling with supply, stability, and subsidies

Urban planner Shane Phillips writes in The Affordable City that housing challenges come down to the “three S’s”: supply, stability, and subsidies. Bloomington and Monroe County struggle with all three.

Stability means people should have protection from unsafe housing and exploitative leases. Bloomington provides some of that through a city government program to register rental units and inspect them once every three to five years, with additional inspections in response to complaints. It covers only rental units inside city limits, however.

Indiana law, meanwhile, limits renters’ rights and preempts many local actions on housing. Local governments can’t, for example, restrict rent increases, adopt inclusionary zoning that requires developers to build affordable units, or force landlords to accept government vouchers as payment for rent.

Subsidies are needed because the market, on its own, won’t provide adequate housing for low-income families and individuals, Phillips writes. Subsidies are available locally through federal housing choice vouchers for tenants and tax credits for developers and apartment owners. But they don’t come close to covering the need, for a variety of reasons, officials say.

But it’s the lack of supply that gets the most attention from public officials and housing advocates.

“Supply is a big thing,” says Deborah Myerson, a planning and housing policy consultant who lives in Bloomington. “You can’t do anything without supply.”

“What’s challenging in Bloomington is the scarcity,” says Radewan of the Eviction Prevention Project. “What’s challenging is the market, and that places that used to be $800 have become $1,200.”

‘I talk to people who grew up here, and they can’t live in their hometown because they can’t afford it.’

—Tonda Radewan, coordinator of the Eviction Prevention Project in Monroe County

Official data are limited on rental housing occupancy rates. But Mark Figg, co-owner of Kirkwood Property Management and a former board member of the Monroe County Apartment Association, says market studies by lenders consistently find rates “in the high 90s to 100 percent, which is basically no vacancies.” As for his company’s 100-plus rental units, he says, “We haven’t had a vacancy, a single vacancy, since 2013.”

Figg says local government restrictions on growth and red tape for developers have made it difficult to meet the growing demand for residential building. As an example, he says, he has been trying for a year to get the city to sign off on his plan to build a duplex in a northside neighborhood. While zoning allows the duplex, his petition to the Board of Zoning Appeals has been delayed several times, most recently when the board didn’t have a quorum.

He credits the current city administration and the 2020 Bloomington Unified Development Ordinance with allowing greater density and more student housing near downtown, but he says the community has a long way to go to catch up.

“As the university grows, as the population grows, we need more housing units,” Figg says. “It’s basic math. If you let the market do what it wanted to do, we would have more vacancies and less rent growth and better market characteristics for tenants.”

Figg concedes that families may be at a disadvantage when competing for rental housing with university students. “If you can spend the money to go to IU, you’ve got enough to pay a decent rent,” he says. “And you probably didn’t grow up in a shabby apartment.”

Residential building permits filed by type of structure. | Graph by Indiana Business Research Center

It’s hard to say how many Monroe County renters are students, but many are. Of IU Bloomington’s 47,000 students, only about one-third live on campus. Among the rest, some live with their parents and some commute from nearby communities. Some, certainly, have parents who can spring for “luxury” apartments at $1,000 per bedroom and up.

But some students do struggle with housing costs, points out Lane Fulton, who holds a master’s degree in public management from IU and has been volunteering as a mediator in Monroe County’s eviction court. Describing many struggles with the property management company that managed a house he rented several years ago, he says tenants often experience “leasing trauma.”

“With everything going up in price, trying to find affordable housing has been mentally taxing and draining, to say the least, for those around me,” he says.

Chase Techentin directs the New Hope for Families emergency shelter in Bloomington and works to help families transition from homelessness to stable housing. He says increasing the housing supply is important.

“The number of units we can look for on a given day is low,” he says. “Even the twelve families in the shelter are competing for one or two units that are available” on a given day.

The Bloomington Housing Authority, which locally administers the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s federal housing choice voucher program, has 1,666 vouchers to award, and nearly all of them are in use. Another 1,500 people are on a waiting list, which is now closed. B-Line Heights (pictured), an affordable rental housing project on North Rogers Street, has 34 units. | Limestone Post

Although New Hope claims an 80 percent success rate in securing homes for families, it’s not quick or easy. “Many families do four or five applications before getting an apartment,” Techentin says. “Some families have done as many as 20 or 30 applications.”

He cites research showing that housing supply and affordability are directly tied to family stability and wellbeing. For example, a study funded by the real estate firm Zillow found that homelessness increased sharply in communities where households pay more than 32 percent of their income for housing.

“Really, increasing the simple number of leases that are available would make a huge difference in the rate of homelessness in our community,” Techentin says.

It’s an example of how housing issues are “all intertwined,” says Mary Morgan, director of housing security for Heading Home of South Central Indiana, a regional initiative aimed at making homelessness “rare, brief and nonrepeating.” Morgan (no relation to Emily Morgan) says she has been surprised at how complex the issue is, with issues of poverty, employment, housing supply, affordability, and other factors overlapping and affecting each other.

Subsidies don’t fill the gap

For families seeking affordable housing, it can help to have a federal housing choice voucher, also known as a Section 8 voucher, which can be available to people who make less than half the area median income. With a voucher, a family pays no more than 30 percent of its income for rent and utilities and the government pays the rest, up to a “fair market” limit set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In 2023, the fair market rent for a two-bedroom unit in Bloomington is $1,124 a month.

But securing a voucher can be challenging for those who qualify by income. The Bloomington Housing Authority, which administers the program locally, has 1,666 vouchers to award, and nearly all of them are in use. Another 1,500 people are on a waiting list, which is now closed.

The list typically opens every 12 to 18 months, usually for just a few weeks, and it can take months to years to reach the top, depending on a renter’s preference points for veteran status, disability, homelessness, or domestic violence, and other circumstances. And getting a voucher doesn’t guarantee housing.

“If they get the voucher, there are definitely challenges to being able to find a place, an affordable place,” says Daniel Harmon, voucher program manager for the housing authority. “Right now, only 61 percent of voucher recipients are successful at being able to lease with that voucher.”

A study funded by the real estate firm Zillow found that homelessness increased sharply in communities where households pay more than 32 percent of their income for housing.

Aside from the difficulty of finding a suitable place where rent is within HUD guidelines, voucher recipients may have trouble finding someone who will rent to them. Background checks are common, and some renters will be tripped up by a previous eviction filing or criminal charge.

Some landlords won’t accept vouchers. Maybe they have had a problem with a Section 8 tenant in the past. Or maybe they’ve heard stories about people who skip rent or trash an apartment.

“I think there’s definitely misconceptions from the landlord’s point of view: that they are bad tenants, they are not going to pay their rent, they’re going to destroy the unit,” Harmon says.

Adds Kate Gazunis, the housing authority’s executive director: “A landlord may have four showings that day, and two of them are voucher holders and two of them are market rate. And he has no issue with any of them. But who can pay the deposit?”

Home buyers are challenged, too

(top) John Zody, director of the city of Bloomington’s Housing and Neighborhood Development department. (bottom) Ron Walker, vice president of CFC Properties. | Limestone Post

Bloomington is a renter town by Indiana standards. Around the state, 71 percent of residences are owner-occupied, census data says. In Monroe County, it’s 58 percent. In Bloomington, two-thirds of residences are rentals, says John Zody, director of the city’s Housing and Neighborhood Development (HAND) department.

Home ownership is a goal for many people, but there, too, Bloomington is a tough market. The median price of homes sold in the county in 2022 was $295,000, well above the Indiana median of $235,000 and one of the highest figures in the state, according to Indiana Association of Realtors data. Home prices have begun dropping, but interest rates are up. Mortgage payments remain expensive.

Wendi Goodlett, president and CEO of Habitat for Humanity of Monroe County, says the cost of building homes has risen, challenging the organization’s work of building decent, affordable homes in partnership with qualifying families. While Habitat relies largely on volunteer labor, Goodlett says, other costs have gone up. Land that’s suitable for development is expensive in Monroe County. Inflation and supply chain problems have driven up the cost of building materials. Skilled labor, which Habitat hires for plumbing, electrical, and drywall work, is more costly. The cost of infrastructure — utilities, curbs and sidewalks, streetlights and trees — adds $50,000 to the cost of building a house.

Some local builders of single-family homes have gone out of business, and others are staying away from building affordable housing. “It’s much more efficient and less challenging for them to build high-end custom homes on large lots,” Goodlett says.

For the families that are accepted into Habitat’s home-building partnerships, there’s urgency to move on from the instability of the low-income rental market. “We see the conditions they’re living in and what they’re paying for those conditions, and it’s disheartening,” Goodlett says.

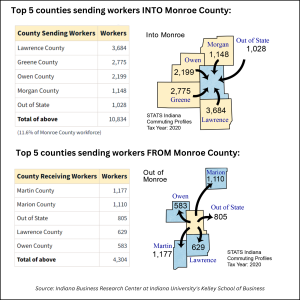

Bloomington-based Cook Medical is responding to the lack of housing by building affordable homes to sell to its employees: but not in Monroe County. They’re in Owen County, where it’s easier to build no-frills developments. Although most Cook Indiana employees work in Monroe County, half of them live outside of the county, says Ron Walker, vice president of CFC Properties, Cook’s real estate arm.

Commuting to work

Overall, more than 10,000 workers commute to Monroe County, many coming from Lawrence County, where the median home price last year was $170,000, or Greene County, where it was $161,000. Driving 30 minutes or more each way has its downsides: a longer workday and more time away from home, wear and tear on the family car, etc. But for many, it’s the only option.

Walker, a former president of the Bloomington Economic Development Corp., says the lack of housing is a problem for employers and an economic development barrier for Monroe County. “There’s kind of a corny phrase: ‘Housing is where jobs sleep at night,’” he says.

Walker, a former president of the Bloomington Economic Development Corp., says the lack of housing is a problem for employers and an economic development barrier for Monroe County. “There’s kind of a corny phrase: ‘Housing is where jobs sleep at night,’” he says.

If the situation is a problem for employers, it hits much harder for people who can’t afford to live and work in Monroe County. For service-sector employees, factory workers, graduate students, and others, housing — both rental and owner-occupied — is increasingly out of reach.

Courtney Stewart, who plans to leave her leased house because of a rent hike of $400 per month, is looking into buying a home. But even though she has a stable, professional job, excellent credit, and a master’s degree, a bank would approve her for no more than a $150,000 mortgage.

“I am looking at purchasing a condo, maybe, because that’s all I could afford,” she says.

Ingrid Davenport, who lost her apartment when The Arch was razed, would love to own a home to share with her 7-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter, but that prospect seems far away.

Emily Morgan, who is moving rather than pay a monthly $800 rent increase, can’t think seriously about home-buying while a full-time student.

“I really don’t know that I would ever be able to own a home, and I’m in my 40s,” she says.

Zody, director of the city’s HAND department, says his primary wish for the housing situation would be to “just get more of it,” at all levels. When people call his office desperate for a decent place to live, he wishes he could always direct them to something that works.

“At the end of the day,” he says, “this is about individual people who need places to live.”

Flyer distributed by the Eviction Prevention Project

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024