The mortgage payment ate away at what was left of Jessica’s budget for the month. She had four children at home in Spencer, Indiana, and they needed to eat, but the money just wasn’t there, and her family didn’t qualify for government assistance.

She asked her sister and father for extra food. Her fiancé scoured his brother’s freezer, hoping to find spare meat.

“It was a horrible feeling,” said Jessica (whose name has been changed to protect her privacy). “We have our cars and we have our house, and here we are not being able to feed our family.”

Not every month is like this. Some months, with meticulous budgeting, they can feed the kids and pay the mortgage, utilities, childcare, and insurance bills.

But one accident — one slip up — sends them over the edge. With limited or uncertain access to food, Jessica’s family, like millions of others around the country, is considered food insecure.

“If someone is out there in my situation, they know,” Jessica said. “They’re working as hard as they can, they’re trying to get as many hours as they can, they’re paying their bills, and they’re still not making it.”

Current approaches to food insecurity

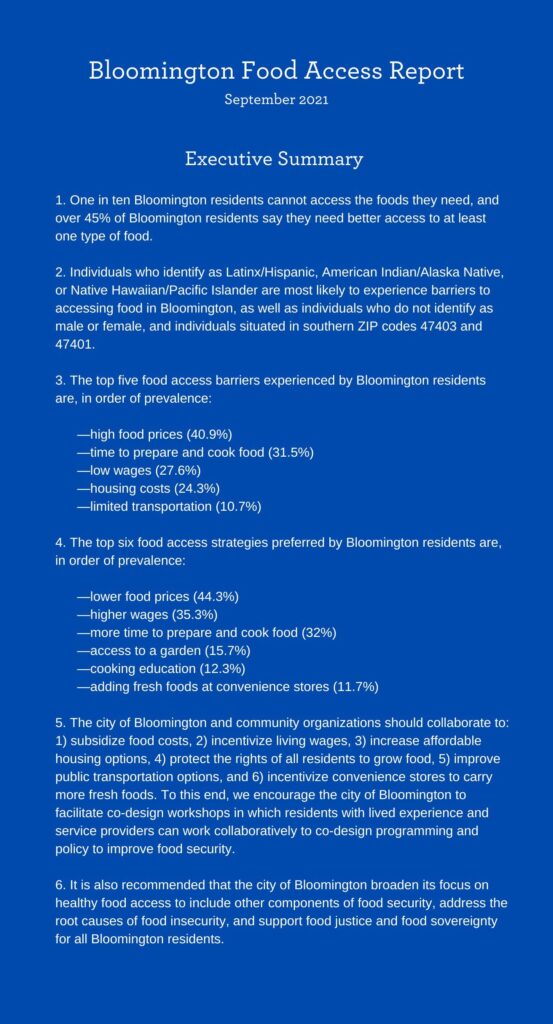

In 2022, 17 million households in the United States experienced food insecurity at some point during the year. In Monroe County, one out of ten Bloomington residents struggles with reliable access to food, according to the Bloomington Food Access Report published in 2021. Based on a survey of community members, the report concluded that “the first clear recommendation to the city of Bloomington and community organizations is to subsidize food costs for low-income households and incentivize living wages throughout Bloomington.”

Implementation of the report’s recommendations appears to have stalled (a topic to be explored in part 3 of this series), but in the meantime, local agencies continue to help residents find access to free or subsidized healthy food.

Randy Rogers, president and CEO of United Way of South Central Indiana | Courtesy photo

Randy Rogers, president and CEO of United Way of South Central Indiana, said food insecurity is ultimately an economic problem. The organization covers Monroe, Owen, Greene, Lawrence, and Orange counties and parts of Brown County and works to connect people to community partners offering the resources they may need to overcome poverty or near poverty. While food insecurity is often discussed in terms of food availability, that doesn’t tell the whole story, Rogers said.

“Food is available if you can afford it,” he said. “We can talk about food insecurity, but if you can’t find it, you can’t afford it, you don’t have a car to get to it, you have to pay your rent, and you’re making a decision — Do I eat or do I pay my rent or do I pay my light bill? — that’s an economic problem.”

Rogers said 23 percent of residents in south-central Indiana are living in poverty, and 46 percent are living one accident or catastrophe away from it.

“There are people who have jobs,” Rogers said. “They’re doing everything they can to make ends meet on a month-to-month, week-to-week basis, but they are one unfortunate incident away from having to make a decision about hunger or rent, take their [children to] childcare, or whatever the case may be. It’s just that ripple effect that causes these challenges for individuals.”

The approach to combating food insecurity is often not holistic, said Angela Babb, a postdoctoral assistant research scientist and food geographer at IU’s Ostrom Workshop. She said more needs to be done to address inadequate wages, unfair job expectations, and job shortages.

“It’s kind of addressing the symptoms of poverty or one symptom of poverty without looking at poverty as the root and how poverty is caused,” Babb said. “We tend to ask in our society why people are going hungry, when we need to ask why people are experiencing poverty.”

Angela Babb, an assistant research scientist and food geographer at the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University | Courtesy photo

Local resources like Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard, Hoosier Hills Food Bank, and the Community Kitchen of Monroe County, and state programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, help alleviate food insecurity in Indiana, but experts and frontline workers call the system patchwork and a temporary solution.

For struggling families, the barriers to qualifying for benefits under programs like SNAP are complex, especially for people who work part-time or temporary jobs or jobs with inconsistent hours. Some people even decline promotions or extra hours because they fear losing eligibility.

“Depending on when they apply, it can look like they have worked more or less hours in the last couple of weeks than they have on average,” Babb said. “It’s one of those administrative barriers that costs a lot in administrative barriers for the state, and then ends up preventing people from being able to access SNAP benefits.”

Jessica, who works as a housekeeper at an inn, faces some of the problems described by Babb in qualifying for SNAP. With her fiancé working as a mechanic and delivering pizza a couple nights a week, they technically make too much to meet the program’s requirements.

She said she would have to quit her job for them to be eligible, but she likes to work and doesn’t want to leave the inn until she has no other choice.

“I don’t want to sit at home,” Jessica said. “I like my job, I like working, I like making money, I like helping out my fiancé, I like helping out my family. It shouldn’t have to come down to me having to quit my job just to qualify for some food stamps.”

The Ostrom Workshop Program in Food and Agrarian Systems studies “the social dimensions of food sustainability including culture, equity, and justice in food provisioning from local to global.” | Photo by Olivia Bianco

Babb recently finished a research project in which she advocates for changes to SNAP policy. These include the asset test — which limits households to a maximum of $5,000 in assets to be eligible — as well as the able-bodied test, which restricts non-disabled adults without children to three months of SNAP in a 36-month period unless they work 20 hours per week.

Even those who receive SNAP benefits don’t always receive enough to get adequate nutrition with rising food costs, Babb said. And it takes more than food not only to live but thrive.

“People need financial assistance for other things, like housing and healthcare, and all these competing expenses with food. Just providing money for food isn’t the answer to ending poverty.”

The Indiana legislature has made moves in recent years to address poverty and food insecurity. Last year, the Senate passed a bill to simplify SNAP renewal for seniors and people with disabilities, and the state is taking part in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s new summer food-stamp program, which will offer families $40 each summer month along with offering group meal services and home-delivered meals.

Indiana State Senator Shelli Yoder, D-Bloomington, said she is also working with Feeding America and the Indiana Department of Education to eliminate asset testing within the SNAP process for families with school-aged children.

“We want Hoosiers to be able to save money,” Yoder said. “We don’t want them to [say], ‘If I save some money, it’s going to actually harm my kids from accessing food.’ So it’s trying to strike that balance, and we’ve been working administratively to make that change.”

Universal basic income

Some communities have begun addressing poverty directly, through the implementation of universal basic income programs. UBI temporarily provides an unconditional minimum income, usually a few hundred dollars per month, for citizens impacted by poverty.

Unlike other government programs, UBI programs do not require pre-approval or tests, and do not limit what the money can be used for. Basic income programs have been shown to improve mental health, get people on track to employment, and improve financial and housing stability.

Sheila Kennedy, professor emerita of law and public policy at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis | Courtesy photo

“The few pilot projects that have been done about a UBI demonstrate that poor people are more productive [and] there’s less crime,” said Sheila Kennedy, professor emerita of law and public policy at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI, soon to be IU Indianapolis). “The benefits are immense.”

Some experts also have suggested a universal basic income as a way to stop food insecurity at the source.

Cities in more than 40 U.S. states have rolled out pilot UBI programs through private or state funding in communities facing the most income inequality and unemployment, including Gary, Indiana.

Kennedy has written in support of UBI on her blog and in her 2019 book Living Together. She said a UBI would be part of a new social contract in line with the founding ideals of the Constitution.

“We like to talk about liberty and freedom,” Kennedy said in an interview with Limestone Post. “Nobody who gets up every morning and worries about sustenance is genuinely free.”

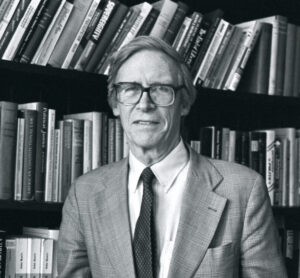

Philosopher John Rawls proposed that leaders organize society as though they were behind a “veil of ignorance” that prevented them from knowing their own and others’ economic, political, or social status.

Philosopher John Rawls | Photo by Jane Reed/Harvard University, used by permission

If everyone were ignorant of their own situation, Rawls argued, they would fight for the most equitable policies to guarantee they would not be disadvantaged when the veil was lifted.

Kennedy used a similar thought experiment in advocating for a UBI. She said a UBI would be a natural policy choice if society were rebuilt from scratch.

“If we were beginning anew, and starting society without all of the accumulated beliefs and cultures that we have, what would make the most sense?” Kennedy said. “What would best contribute to human flourishing? A basic income would be a huge part of that.”

Kennedy said she envisions paying for a UBI through an increase in taxes, especially on very wealthy households. However, she said a basic income would reduce the need for existing welfare programs and therefore be far less costly than many people assume.

“By and large, it would replace what is a very inadequate and patchwork system with a universal system,” Kennedy said. “It would probably save us a lot of money.”

UBI in Indiana

In Indiana, the city of Gary — which has been reported to be one of the poorest cities in the state — rolled out a yearlong guaranteed income pilot program in May 2021, the first of its kind in Indiana. The Guaranteed Income Validation Effort, or G.I.V.E., distributed $500 a month to 125 citizens for 12 months. Recipients were chosen from a survey sent out across the city, and only had to be 18 years or older with a yearly income of less than $35,000.

The pilot program — funded by Gary Mayor Jerome Prince, the organization Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, and other organizations and donors — also offered financial literacy classes and information about educational opportunities at IU Northwest. The program ended in 2022, but director Burgess Peoples said G.I.V.E. still offers financial classes and workshops in an effort to expand the program’s reach and keep participants on track.

“There were so many different things that we were able to tap into that residents in this particular city, the city of Gary, did not know existed,” Peoples said.

In Gary specifically, food disparity is the biggest problem, Peoples said — fresh produce and other healthy food are often not available at affordable prices, leaving many people to rely on shopping for fried and sugary foods. She said she often sees families with multiple children struggling to afford food because they make too much money to meet SNAP eligibility — even if the parents work relatively low-paying jobs.

“You fill up your tank with all the bad stuff,” Peoples said. “You can go to any other community and you’ll find a whole section on vegan food or healthy choices. You don’t get that in some of the communities that are impoverished.”

The G.I.V.E. program allowed recipients the extra money they needed to do things like pay bills, get their cars fixed, and repair their homes. Multiple people started their own small businesses by using the extra money to buy supplies, Peoples said. Others became new homeowners, and senior citizens in the program could purchase essential medications without worrying how they would make rent.

Crimson Cupboard at Campus View Apartments is run by volunteers to help students with food insecurity in Bloomington. | Photo by Olivia Bianco

The success of programs like G.IV.E. begs the question of how such an effort might be established in communities like Bloomington.

The city has made a small foray into a similar kind of initiative by instituting an ordinance that mandates a minimum wage of $15.29 an hour for full-time city employees. Babb, of the Ostrom Workshop, says this could be a stepping stone to a universal income program.

Kennedy said implementing a UBI in Bloomington would require deep research into what worked and didn’t work in the pilot programs from recent years.

“You go out and you say, ‘Which cities have initiated a pilot program of this sort?’” Kennedy said. “‘Which ones have worked out well? What were the obstacles they encountered? What were the political arguments pro and con?’ And then you take that information and you build your own proposal around it.”

Kennedy said that although the problem is largely economic, the lack of widespread political support presents a significant challenge to starting basic income programs. A cultural bias against welfare makes it difficult to market the idea of a UBI, she said.

“We have people screaming ‘socialism’ whenever government does something that has been demonstrated the government can do more efficiently and less expensively,” she said.

In her view, the best way to popularize a UBI would be to emphasize the fact that it is universal and not limited to a particular group. She said the accessibility of Medicare and Social Security explains why Americans generally oppose cuts to those programs.

“The reason is that those are universal programs,” Kennedy said. “Everybody pays into them, and everybody who lives long enough benefits.”

Indiana State Senator Shelli Yoder | Courtesy photo

Yoder, the state senator from Bloomington, said she would like to see the Indiana legislature form a committee during the 2024 interim session to study the feasibility of universal basic income.

“Too often, the supermajority makes decisions solely based on the cost on the front end without thinking ‘big picture’ of the cost,” she said.

Yoder pointed to school bus drivers and childcare workers as examples of jobs that fill essential needs but are not paid adequate wages.

“You could go on and on and on where these are integral jobs, but they just simply don’t pay enough to pay the bills,” Yoder said. “We as a state could look at that and say, ‘Okay, how much would it cost? What would it look like?’”

Peoples, the director of the UBI pilot program in Gary, said she thinks more cities across the state should develop similar programs to G.I.V.E. to help communities struggling with poverty.

“We are giving them a hand out of every public program that has been keeping the foot on their neck for the past decade,” Peoples said. “You have people in your community who do not want to live in poverty. How about giving them a hand up? Invest in people.”

Jessica said even a little government assistance would ease the burden on her family.

“I’m not asking for a thousand dollars like a lot of people get,” she said. “One hundred fifty, two hundred dollars a month would help out our family a lot.”

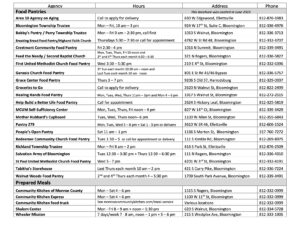

List of Food Pantries and other sources

Prepared by Hoosier Hills Food Bank.

Find food in Brown, Lawrence, Martin, Owen, and Orange counties, y en español: hhfoodbank.org/find-food/.

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024