Editor’s note: This is the fifth article in a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. Deep Dive has been chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the 2023 Nonprofit News Awards.

Indiana is in the throes of an energy transition, on the cusp of figuring out a resilient and reliable energy palette to meet climate change impacts now upon the state. Playing their part with their aggressive 2018 Sustainability Action Plan, and now their collaboration with Nashville and Columbus with Project 46, Bloomington and Monroe County are part of that transition.

What happens in energy is primarily the domain of the state and national government, as well as private utility and energy companies. | Photo by Benedict Jones

Still, with energy management there is only so much a city and county can do. What happens in energy is primarily the domain of the state and national government as well as private utility and energy companies. They determine the speed and type of renewables utilized and the laws to facilitate those changes. In the end, climate change and extreme weather outcomes drive it all. While some counties are trying to influence what happens locally, those efforts ultimately go only so far.

To understand Indiana energy, one must understand how energy is evolving in the U.S. and how it is interconnected. The context of what’s happening throughout the United States on its grid is critical. Now, with some transmission lines more than 30 years old and about 65 percent of circuit breakers more than 35 years old, the U.S. grid is aging and fraying.

The question becomes, can the grid withstand the integration of new energy sources like wind and solar, the increasing pressures of severe weather, transmission congestion, and cyberattacks to the grid. (The bond credit rating service Moody’s says utilities and hospitals are the industries with the greatest risk of cyberattacks.) This is the question that is keeping energy experts, utilities, and state and federal governments up at night.

A ‘patchwork of operators’

In the U.S., power originates from three separate power grids, the Eastern Interconnected Grid, which runs east of the Rocky Mountains; a Western Interconnected Grid, which runs west of the Rocky Mountains, and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT). U.S. power grids comprise 360,000 transmission lines stretching 160,000 miles, including more than 7,300 power plants for more than 145 million business and residential customers.

Generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity are the spokes of energy, though reliability, resilience, and capacity within these grids are necessary for dependable and consistent power. Without them, power doesn’t get to the consumer.

A complicated system, the U.S. grid is a network of wires that traverse the continent and connect with regional private operators who then transmit and distribute power. Some call the grid “a patchwork of operators with competing interests,” meaning that companies producing energy from solar, wind, coal, and natural gas all compete among themselves to provide power to the U.S.

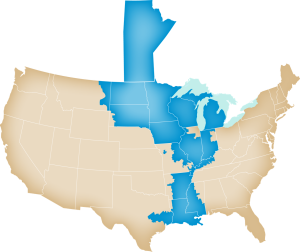

Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) is one of nine independent regional transmission organizations that transmit energy in the U.S. It covers part of Canada and all or part of fifteen states, including most of Indiana. MISO ensures that power is transmitted via power lines to residential homes, businesses, universities, and anyone who needs power. | Map by Kaceyageorge via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Seventy percent of the privately owned grid is more than 25 years old, meaning U.S. power is constantly at risk due to a weakening and congested grid. A congested grid means transmission capabilities are risky and insufficient to meet consumers’ growing needs, exposing the grid to cyberattacks and ever-more-frequent extreme weather.

Right now, that power originates from 19 percent coal, 20 percent renewables (wind, solar, biomass, hydro, and geothermal), 40 percent natural gas, and 20 percent nuclear. Within the three U.S. power grids, nine independent regional transmission organizations (RTOs) transmit energy. The Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) covers fifteen states, including most of Indiana. MISO ensures that power is transmitted via power lines to residential homes, businesses, universities, and anyone who needs power.

Within the U.S. grid and RTO areas are almost 3,000 electric distribution companies, or utilities. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) classifies utilities into three different types of ownership: investor-owned, cooperatives, and publicly owned or managed utilities. For example, South Central Indiana REMC is a cooperative, whereas Duke Energy is an investor-owned utility. Paoli Light and Water Department is municipally (or publicly) owned utility.

Approximately 42 million people in rural communities get power from rural cooperatives, a public utility born of the 1930s New Deal by President Franklin Roosevelt. The same deal created the Tennessee Valley Authority, a primary U.S. power source today.

Old and new power transmission poles in downtown Bloomington. Jeff Danielson, vice president of advocacy for the Clean Grid Alliance, said, “It’s time for Americans to think about our grid as an interstate superhighway and build it so we can move power around.” But now, he said, “our grid is like a balkanized country.” | Photo by Benedict Jones

Because the U.S. power grid and RTOs are privately owned, there is a tendency to think of the overall power scheme as operating independently. But in reality, Roosevelt’s New Deal system no longer works. The U.S. power needs are more significant now. States get power from other states. Energy can be stored for the future. The entire system is interconnected and interdependent in many ways.

“We should think about it like Dwight Eisenhower did when he created the interstate highway system,” said Jeff Danielson, vice president of advocacy for the Clean Grid Alliance, a nonprofit public-interest advocacy organization that focuses on expanding the North American grid. Danielson says the new grid is a “shared responsibility.”

“[Interstates] can move people and products throughout the country very efficiently,” said Danielson. “It’s time for Americans to think about our grid as an interstate superhighway and build it so we can move power around.” But right now, said Danielson, “our grid is like a balkanized country.”

With the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), $397 billion earmarked for reducing energy costs and accelerating the energy infrastructure incentivizes growth on all energy fronts. No longer is the U.S. relying only on coal-fired plants to provide power. It’s diversifying and building through a competitive bid process to increase clean energy, battery storage, and other innovations.

“It’s the largest infrastructure investment in American history,” said Danielson. “The infrastructure build-out will rival [19th century] railroad development.”

Those dollars are now reaching Indiana. “So for the next ten years, the duration of IRA tax credits, companies will be competing against each other to build what is one of the largest infrastructure build-outs in American industry,” said Danielson.

Indiana’s energy landscape

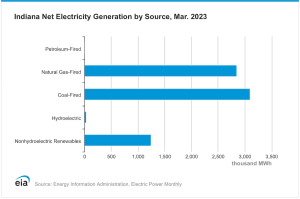

Regulated by the Indiana Energy Regulatory Commission (IERC) and the Indiana General Assembly (IGA), Indiana’s primary energy sources are coal, natural gas, and a growing renewables market.

Indiana State Representative Matt Pierce (District 61) participated with eleven other Hoosier legislators on the 21st Century Energy Policy Development Task Force to evaluate energy efficiency efforts, energy investment districts, stranded utility assets, and other energy issues. | Photo by Benedict Jones

In 2019, the IGA appointed the 21st Century Energy Policy Development Task Force to evaluate energy efficiency efforts, energy investment districts, stranded utility assets, and other energy issues. State Representative Matt Pierce (District 61) participated, along with eleven other legislators, four Democrats and eight Republicans.

In October 2022, they issued their report for the IERC to follow, basing Indiana energy policy on five pillars: reliability, resilience, stability, affordability, and environmental sustainability.

“On one level, that’s the broadest policy provision out there,” said Piece. “But really, the question is, what will IERC do with that? Will they change their analysis to include all those, or is it just a bill on the shelf?” Pierce wasn’t sure what would happen.

Since the 1960s, Indiana has been a coal-fueled state. As of July 2022, 34 coal-fueled power plants dominate the state, the highest number in the U.S. According to an energy profile analysis by EIA, Indiana is the fifth largest producer of bituminous coal (the most abundant type of coal) and the eighth largest producer overall, even though the coal mined in Indiana does not meet the state’s demand.

Thus far, 5,200 megawatts of coal-fueled capacity have been retired since 2010. The EIA defines capacity as “the maximum level of electric power that a power plant can supply at a specific point in time under certain conditions.” Another 4,800 megawatts are expected to be retired in the next decade, with the fifth largest power plant, Merom Generating Station in Sullivan County, retiring this year. For comparison’s sake, New York City uses 11,000 megawatt-hours of energy per day; one megawatt is needed to power 100 homes.

In February 2022, Hallador Energy reported that it had acquired Merom. According to the EIA, Indiana’s coal-fired electricity generation continues declining, from 90 percent generation in 2010 to 58 percent generation of total energy capacity in 2021.

Phasing out coal

Coal plants are expensive to run, but they stand to get increasingly expensive with the EPA’s power plant rules that were proposed on May 11. The rules create new carbon pollution standards, such as carbon capture or storage technology, to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emitted to the environment. According to a recent article from The Conversation, only a handful of plants use this technology to capture and transport carbon to oil fields for enhanced oil recovery.

AES Indiana converted its Eagle Valley plant in Martinsville from coal to natural gas, but, according to WFYI, the site could be sending water contaminated with coal ash into the White River. | Photo by Benedict Jones

Adding to the cost is the price of building new infrastructure to transport CO2, although U.S. Department of Energy loan programs and IRA tax credits may offset some of these costs. At this time, however, all these things have yet to be in place across the U.S. to help meet Biden’s 2035 goals of 100 percent carbon-free electricity and net zero emissions by 2050.

The economic impact of retiring these plants is huge. Based on a report by the Indiana University Public Policy Institute, the statewide direct economic impact of closing four plants — Schahfer, Michigan City, Petersburg, and Rockport coal-fueled plants — “may affect as many as 652 jobs, $77.5 million in employee compensation, and $354 million in GDP. The economic ripple effects may affect an additional 1,732 jobs, $98.4 million in employee compensation, and $184.7 million in state GDP.” Job loss and stakeholder wages and benefits are often difficult to recover for communities but can be influenced by tough labor markets or jobs available in other regions near retired utility plants.

Despite this, according to the Indianapolis Star, four of the five investor-owned utilities operating in Indiana — CenterPoint Energy, NIPSCO, AEP (dba Indiana Michigan Power), AES Indiana (formerly Indianapolis Power & Light), and Vectren — have announced plans to phase out coal by 2030. Duke Energy is the only utility planning to continue burning coal beyond 2030.

“All in all, MISO’s Future Planning Scenarios currently anticipates approximately 42,000 megawatts of coal generation to retire by 2042,” said Brandon Morris, communications advisor for MISO.

Because of Indiana’s continued reliance on coal, the EIA ranks it the 8th highest state for greenhouse gas emissions, emitting 154.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into Indiana’s skyline.

“

Seventy percent of the privately owned grid is more than 25 years old, meaning U.S. power is constantly at risk due to a weakening and congested grid.

”

Because of coal plant retirements, utilities and other large companies are changing the energy landscape in Indiana. “It is important to have a diverse set of generation sources across our footprint so we can leverage different forms of generation at different times,” said Morris. “As the grid transforms, this will be further magnified.”

“The utilities now are moving to renewable energy, and we are hearing from many manufacturers like big auto manufacturers and Eli Lilly people saying they want a zero-carbon footprint,” said Pierce. “Utilities want to go to renewables, so we [Indiana legislators] have to manage this transition to renewables.”

Baseload power

The Indiana legislature has mixed attitudes toward the transition to renewables. On the one hand, there are advocates of baseload power, the idea that Indiana should develop its power base and not depend on power obtained from other states to provided the needed energy.

“It’s an old-school way to think about utility and energy service,” said Kerwin Olson, executive director of Citizens Action Coalition, based in Indianapolis. “That’s the old Edison Pearl Street station model where a baseload power plant delivers electricity over long stretches of transmission lines.”

Kerwin Olson, executive director of Citizens Action Coalition, based in Indianapolis, says baseload power is “an old-school way to think about utility and energy service.” | Photo by Benedict Jones

Indiana is not doing a good job with that model of baseload power, said Olson.

Pierce agrees. Here, the current legislative attitude on baseload power is that “we can’t be held hostage to some nuclear power plants in Illinois and what they might charge us or rely on intermittent winds from South Dakota,” said Pierce. “We have to have our stuff.” But the general trend of sharing resources and having power available at all times, according to Pierce, democratizes power and increases reliability. “You can put together a very robust, resilient system that way,” he said.

Other attitudes are that renewable energy is just not reliable. Wind doesn’t blow when it’s needed. The sun doesn’t always shine when it’s needed. Or too much wind or solar energy is cultivated and then goes to waste. Skeptics of renewables, Pierce said, “love to point to California, and say, ‘They’re the king of renewables and look at them. They got brownouts and blackouts and all kinds of mayhem.’” Right now, acceptance of renewables is being pushed mainly by power utilities, said Pierce.

“On the ground, the Indiana House is a microcosm of the polarization we see across the country,” said Olson. “There is not the general hatred of renewable energy that many people think exists.” Still, said Olson, legislators are concerned and skeptical about renewables’ reliability, land use, and coal plant retirements.

Ultimately, the fact that utilities are driving the movement toward renewable energy makes it easier for the legislature, said Olson, because “all fifty statehouses across the country are bought and paid for by the electric and gas investors on utilities, so whatever they say goes.

“When the utilities are driving these changes,” said Olson, “it makes it easier for conservative venues like Indiana to accept a necessary transition to renewables.”

Dormant commerce clause

Recent actions at this year’s legislative session show the willingness to let utilities make those calls. Gov. Eric Holcomb recently signed HB 1420, giving Indiana utility companies the right of first refusal to build, own, and operate new transmission lines in their service area.

Olson said legislators in the Indiana Statehouse (above) are concerned and skeptical about renewables and coal plant retirements. But, he said, because utilities are driving the movement toward renewable energy, “it makes it easier for conservative venues like Indiana to accept a necessary transition to renewables.” | Photo by Benedict Jones

Twelve years ago, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission passed a rule eliminating cross-border project rights. Initially, utilities had the right of first refusal for transmission within their territory. While HB 1420 does require competitive bidding when a subcontractor is used for construction portions of the project, utilities retain a right to first refusal, something CenterPoint Energy supported.

“We believe it is reasonable for Indiana-based utilities to be best positioned to build transmission that integrates with existing equipment,” said Erin Merris, senior communications specialist for CenterPoint Energy. “The legislature added consumer protection to the bill by requiring utilities, to the extent commercially practicable, to use competitive bid engineering procurement and construction contract and by providing for online review of the project by IERC during construction.”

Critics like Olson at Citizens Action Coalition disagree, saying that when competitive bidding is open to all companies — not just to utilities — innovation increases and consumer costs are lowered. Within MISO’s jurisdiction, six states, including Indiana, carry this right-of-first-refusal law.

But these rulings remain in flux. An August 2022 decision by the 5th Circuit Court in Texas condemned the right to first refusal for the Texas power grid, ERCOT, as a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s dormant commerce clause. (According to Lawshelf.com, the clause says “states cannot discriminate against interstate commerce nor can they unduly burden interstate commerce.”) This means that Texas, in creating a right to first refusal, violated the commerce clause despite the fact that Congress had never created regulations for that particular situation. The U.S. Supreme Court now has the case on its docket.

“Iowa too just ruled their right of first refusal was unconstitutional under their state constitution,” said Pierce. “They had some pretty harsh things to say about it initially.” Pierce believes that eventually the federal government and Congress may in the future pass a statute that will deal with this issue.

Natural gas and nuclear power

Indiana’s primary energy footprint includes coal, wind, solar, and natural gas.

The EIA states that Indiana is one of the nation’s top consuming states of natural gas. Though it doesn’t have significant reserves, according to EIA’s energy profile for the state, Indiana does produce some natural gas, with a 4 billion cubic feet output of natural gas in 2020, smaller than .04 percent of the U.S. total. The rest of Indiana’s supply comes from interstate pipelines that snake across the state, mostly in east-central Indiana.

One result of baseload power attitudes is that utilities are now building natural gas plants. CenterPoint Energy is building two new natural gas plants and a pipeline near Evansville, investing more than $76 million and upgrading 115 miles of pipeline.

CenterPoint Energy is building two new natural gas plants and a pipeline near Evansville, Indiana, investing more than $76 million and upgrading 115 miles of pipeline. Shown here is CenterPoint Energy’s natural gas station in northern Monroe County. | Photo by Benedict Jones

The Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission (IURC) approved the construction of two natural gas combustion turbines for the project. “The bare steel and cast-iron infrastructure will be replaced with new industry-graded plastic,” said Merris of CenterPoint Energy. Plus, CenterPoint is also upgrading existing pipelines. “Since 2008, nearly one thousand miles of natural gas pipelines have been replaced in Indiana, which has reduced leak calls and natural gas emissions from the distribution system,” she said.

By building new natural gas plants, said Pierce, “the idea seems to be that coal may be going away, but to replace it and to preserve baseload power, natural gas needs to take its place.” But the problem is that natural gas is responsible for 33 percent of U.S. methane emissions and 4 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. It’s not “clean” energy. So, ten to fifteen years down the road, Pierce contends, the government may “really crank down on carbon emissions,” making these expensive natural gas plants obsolete, a possibility given Biden’s ambitious goals.

According to the EIA, Indiana does not have nuclear power. However, in 2022, Gov. Holcomb signed Senate Bill 271, which directed the IURC to create rules for construction and lease for small modular nuclear reactors.

Recently Duke Energy and Purdue University conducted a feasibility study on the possibility of using small modular nuclear reactors as an option to reach zero carbon emissions at Purdue University. At this time, according to the feasibility study’s interim report, no decision to build a nuclear plant has been made.

Small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) can be built in a factory and shipped to a location for generating nuclear energy. They typically produce up to 300 megawatts of clean energy and have been supported by the Indiana legislature. They are, however, vigorously opposed by the Citizens Action Coalition. The nuclear industry, said Olson, “have half this country convinced that nuclear power is essential to address climate change, even though they’ve delivered nothing in the last thirty years.”

Thus far, production on SMRs has been slow, and regulatory approval from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission is a lengthy and ponderous process. At present, there are no SMRs built in the US at this time.

Fighting wind and solar in Indiana

Renewables like wind and solar are rapidly developing in the state. Hydropower, solar, and wind projects accounted for 20 percent of electricity generation in 2021 and will increase by 24 percent this year. A Ball State University study found that lower-cost and cleaner-energy options will grow as coal plants retire, especially as they become cheaper. In addition, IRA dollars and tax credits are fueling growth in these areas.

EIA’s 2023 Annual Energy Outlook projects that solar and wind will generate most of the electricity in the U.S. by 2050.

In Indiana, the Solar Energy Industries Association ranks Indiana 19th in the U.S. for total installed solar capacity, with just under 1,641 megawatts, enough to power 194,474 homes.

The Indianapolis International Airport has the largest solar farm of any airport in the world, generating enough electricity to power 3,200 average homes. | Photo by Benedict Jones

Indiana currently hosts eight projects with 1.4 gigawatts solar power capacity and 2.3 gigawatts of wind turbine power. CenterPoint Energy has five projects in various stages of development, plus a wind generation project still awaiting IURC approval, said Merris. By 2030, they expect more than 80 percent of their electricity will be wind and solar.

Overall, 91 solar companies operate in Indiana, with the state’s solar market valued at $1.9 billion.

The Environmental and Energy Study Institute found that wind, solar, hydropower, biomass (energy from animal and plant refuse), and geothermal projects brought 504,600 jobs to the U.S. Wind energy jobs were the only sector not to decrease in jobs in 2021, whereas coal plant production lost jobs.

Brandon D. Morris, communications advisor for Midcontinent Independent System Operator, says having a diverse set of generation sources is important “so we can leverage different forms of generation at different times.” | Courtesy photo

A report published by Clean Jobs Midwest says jobs in clean energy and clean transportation grew in Indiana by almost 7 percent — or 86,215 job — in 2021, including 89 percent lost during the COVID-19 pandemic that were regained. Wind projects deliver $1.9 billion to local and state tax revenues and land lease payments with farmers yearly, as reported by American Clean Power.

According to MISO’s Response to the Reliability Imperative, updated in 2023, aging coal resources now mean that other resources like wind and solar must ramp up to avoid a reliability issue in MISO’s service areas.

But renewable energy fights an uphill battle in Indiana due to increasing debates across the Midwest about the growth of renewables. While farmers overwhelmingly support wind and solar projects, some Indiana counties are against these measures.

For some farmers, leasing their farmland to renewable companies has been a lifeline, helping to recover costs incurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, severe weather, and rising expenses due to inflation and the Trump administration’s trade war with China. Farmers typically enter into a lease or an easement agreement to put wind turbines on their land. Initial lease terms are 25 years but can go up to 50 years. Royalty payment per turbine can vary from $6,000 to $8,500, based on gross revenue per turbine. According to Wind Watch, a wind turbine needs approximately sixty acres for airflow buffer, although only 3 percent is used for the turbine equipment.

Federal incentives for farmers

In May 2023, UPI reported that the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced $10.7 billion for rural communities to develop affordable clean energy. Earmarked for rural electrical cooperatives, renewable energy companies, and electric utilities, the grants and loans will be available through the USDA’s Empowering Rural America program and Powering Affordable Clean Energy program.

Often the complaint about large wind and solar farms now is that they take up too much farm acreage, thus destroying, as some rural farming advocates say, the nostalgia of rural farming.

Some people complain that nausea, headaches, and other symptoms result from “wind farm syndrome,” a condition that, according to a Finnish study, doesn’t exist. Meadow Lake Wind Farm (above), in Benton and White counties in northwestern Indiana, will produce enough electricity to power 203,000 homes. | Photo by Raed Mansour, CC BY 2.0

But other county residents’ objections have been based on visual impact and noise, while other debates are ideological. Still others are concerned about property value impacts. Some complain that nausea, headaches, and other symptoms result from “wind farm syndrome,” a condition that, according to a Finnish study, doesn’t exist. These complaints are manifesting throughout the country and not just in Indiana. Some complaints were grounded in disinformation from groups with ties to the fossil fuel companies.

Local zoning laws influence where and how counties can build renewable projects. According to Tamara Ogle, community development regional educator at Purdue Extension, 54 of Indiana’s 92 counties have commercial solar energy regulations, 52 have commercial wind regulations, and eight ban wind projects in any zoning district. To date, Monroe County and Bloomington have not objected to such projects.

“Commercial solar is relatively new in Indiana, and with that comes many questions or concerns from community members and neighbors,” said Ogle.

The Indiana General Assembly has tried to take action to deal with county resentment toward renewables. In 2021, legislators introduced HB 1381, legislation that would have overruled county ordinances and create statewide standards for wind and solar placement farther from homes and other businesses.

But the bill received significant pushback from the counties and ultimately failed. A subsequent bill, SB 411, was passed in March 2022 that established voluntary default standards for wind and solar projects where county compliance designates the county as a “solar energy ready community.”

“The number one challenge in Indiana is that you have local counties who have either passed moratoriums or effective bans [on wind and solar projects],” said Danielson of Clean Grid Alliance. “We are trying to do everything we can to work with local communities to reverse some of those decisions, which we believe were not evidenced based.” Danielson believes if these decisions can’t be reversed, Indiana will not be able to meet its energy goals.

“The number one challenge in Indiana is that you have local counties who have either passed moratoriums or effective bans [on wind and solar projects],” said Danielson of Clean Grid Alliance. “We are trying to do everything we can to work with local communities to reverse some of those decisions, which we believe were not evidenced based.” Danielson believes if these decisions can’t be reversed, Indiana will not be able to meet its energy goals.

As for consumers interested in generating their own energy, Indiana is not a consumer-friendly state. Hoosiers pay an average of $127 monthly for their energy bill, whereas Illinois consumers pay $96 per month and Ohio consumers pay $112 per month.

A 2017 law, SB 309, phases out net metering, which subtracted excess power generated by solar panels owned by consumers toward a their utility bill. Olson is optimistic, saying, “We can create better policies that would encourage and incentivize” consumer involvement, but for now, “net metering is dead.”

With renewable energy the fastest growing segment in energy, storing energy becomes necessary. Battery storage technology can solve power intermittency problems by storing extra energy produced by wind and solar projects.

Storage technologies, especially lithium-ion batteries, are becoming more efficient and economically viable. The EIA predicts that U.S. battery storage capacity will increase significantly in 2023, and from 2023 to 2025 they expect to add another 20.9 gigawatts, powering nearly 16 million homes for one hour depending on their size, number of occupants, and number of appliances running.

In Monroe County and Bloomington

Monroe County and Bloomington are both doing their part to influence the progress that Indiana is making toward combating climate change. In 2018, Bloomington created the Sustainability Action Plan that covers electrifying city buses and attempts to reduce energy for city government buildings as well as other attributes.

A power substation in Bloomington. | Photo by Benedict Jones

Right now, according to Shawn Miya, Bloomington’s assistant director of sustainability, the municipality has 29 solar panels installed at Dillman Road Wastewater Treatment Plant and smaller systems on rooftops at parking garages and community centers.

In 2016, the Monroe County Planning Department issued the study “GIS Analysis of Solar Energy Potential in Monroe County,” which concluded that nearly three-quarters of the county could accommodate solar panels. As a result, the solar tech company Solarzentrum has proposed a solar panel farm on 15 to 20 acres, but no site has been identified to date. In a plan endorsed by the Monroe County commissioners, Hoosier Energy installed a solar farm in Ellettsville.

According to Tammy Behrman, assistant director of the Monroe County Planning Department, Monroe County has not had any inquiries for solar farms in the last two years. A solar farm is defined under Monroe County Zoning Ordinances as “a commercial facility that converts sunlight into electricity, whether by photovoltaics or other conversion technology, for the primary purpose of wholesale sales of generated electricity.”

In an email, Monroe County Councilmember Cheryl Munson stated that several years ago, the closed-but-managed landfill north of Bloomington, an area managed by Monroe County Solid Waste Management District, was once considered for a solar farm. As board chair of the District, Munson wrote, “I contacted Duke [Energy] and they were not interested at the time.”

While Duke Energy has no solar or wind projects in Monroe County or Bloomington, a 17-megawatt solar plant at Crane Naval Base became operational in February 2017, and a battery storage capacity of 4.95 megawatts became operational in December 2020.

The impact of extreme weather

Extreme weather across the U.S. has impacted an already fragile grid. Last summer, MISO reported capacity shortfalls for the 2022 summer months and into 2023. In the North American Electrical Reliability Corporation’s 2022 Summer Reliability Assessment, the National Energy Regulatory Commission went so far as to label MISO as a “high-risk” category for potential power outages.

For the 2023 summer, the Federal Regulatory Commission released its annual summer energy market and reliability report, which predicted temperatures are likely to be 50 to 70 percent higher than average temperatures for June through September in most of the U.S. While all regions will have sufficient generating resources with increased solar and wind generation and battery capacity, MISO may face acute energy shortfalls only if extreme weather occurs.

But the future doesn’t look promising. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), anticipated impacts from El Niño and continued greenhouse gas emissions may push the world’s climate beyond the 1.5°C warming limit set by the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. El Niño occurs when surface waters warm in the Pacific Ocean and disrupt atmospheric circulation, which can create extreme weather patterns like strong storm systems, rain, and flooding. The WMO believes that there is a 66 percent chance of exceeding that threshold for at least one year between 2023 and 2027. Exceeding this limit could result in extended heatwaves, intense storm systems, and wildfires.

In May 2023, the WMO reported that the world would soon see this 1.5°C warming earlier than expected. The previous year’s report stated a 50 percent chance of warming. This may be another hot year, and 2024 may be warmer than 2023.

“

“We are hearing from many manufacturers saying they want a zero-carbon footprint.” —Indiana State Rep. Matt Pierce

”

In Indiana, First Street Foundation predicted that the state is part of an “Extreme Heat Belt” that forms along the Mississippi River. An extreme heat belt is a region expected to see days above 125° Fahrenheit. According to the report, Indiana can expect to see increases in hot weather over the next 30 years, and counties like Martin and Posey can expect much hotter temperatures, 104.5°F, for extended periods. Monroe County will also see increased hot weather.

As energy changes so must state, county, and local governments change their approach on how to deal with these changes. Climate change is rapidly forcing that issue and as a result, maintaining a transitionary position is no longer feasible.

While energy policy is and will continue to be, for the time being, the prerogative of the federal and state government, counties like Monroe County can make their assessments and begin by educating their community as to why it is important to be prepared especially for extreme weather events.

But states must understand that diversifying energy sources to include renewables and interconnecting those sources increases reliability as well as resilience. Clean energy economics means, Danielson believes, that Indiana should hook to the grid as if it were entering onto a highway entrance ramp. To do this, federal and state governments, RTOs, and utilities must begin to imagine a grid on a larger scale — as one that not only connects states and local communities to energy but one that connects the nation as a whole to it. Without that interstate, society’s chances of surviving climate change may be impossible.

A solar farm transmission station in Indianapolis. | Photo by Benedict Jones

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024