Editor’s note: This is part of a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. Read more about the collaboration at the end of this deep dive into the Hoosier National Forest.

‘In Wildness is the Preservation of the World.’

So said two of the most influential muses in my 40-year career as an environmental journalist, photographer, and author. In 1854, Henry David Thoreau said it in Walden. Eliot Porter, the Ansel Adams of color nature photography, used it as the title for his masterful 1962 monogram, which is recognized as the first coffee-table book ever published.

Thoreau’s sentiment has likewise been shared by Southern Indiana preservationists I’ve given voice to throughout my career and laid the foundation for the Charles C. Deam Wilderness Area’s establishment as the state’s only permanently protected wild area in 1982.

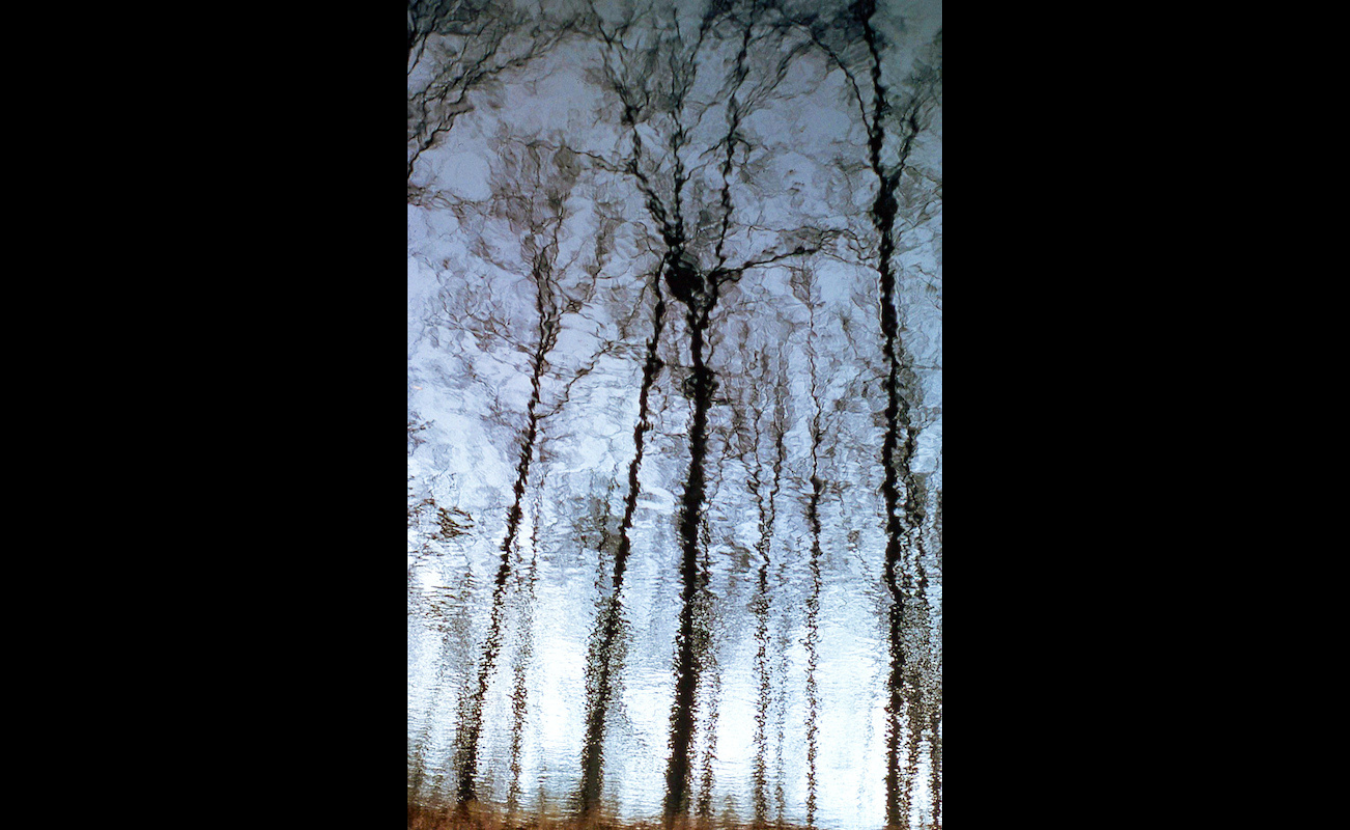

Terrill Ridge Pond, March 2016, Digital image | As part of the land’s restoration that began in the 1950s, the Roosevelt-era Civilian Conservation Corps built wildlife ponds like this one just north of the Brown–Monroe County line. It sits on a spur off the 3.8-mile, in-and-out Sycamore Trail, whose trailhead is located at the Hickory Ridge Lookout Tower.

It’s also a proposition I’ve contemplated since I began exploring and researching the Hoosier National Forest in 1975, seven years before the Deam was established. My 1986 final master’s project at the IU School of Journalism was titled Clearcutting the Hoosier National Forest: Professional Forestry or Panacea? In 2020, I wrote an as-yet unpublished coffee-table book for IU Press called Rewilding Southern Indiana: The Hoosier National Forest.

What’s achingly clear 169 years post-Walden is that Thoreau’s salvation declaration is self-evident today. When humans self-destruct, the world will return to wildness, from which life will evolve again.

The question today isn’t whether a tiny patch of undisturbed Southern Indiana forestland will save the world in the Thoreauvian sense. It’s whether the Deam’s nearly 13,000 acres are enough to help save the humans who need it now — how to prevent them from loving it to death.

So, when discussion turned to a Limestone Post project on the Hoosier National Forest, I naturally gravitated toward wildness for the first focus.

Besides, the Deam is the place where my half century of Hoosier National Forest exploration began.

And, in what can only be described as an instance of divine intervention — serendipity at least — we learned through the reporting process that U.S. Sen. Mike Braun was introducing legislation that more than triples Hoosier National land around the Deam that will be managed to promote activities like hiking, horseback riding, and camping and to protect water quality in Lake Monroe.

At a September 30 Indiana Forest Alliance (IFA) meeting in Brown County, Braun’s chief of staff, Josh Kelley, unveiled details to add 15,300 acres to the 12,953-acre Deam and to designate another surrounding 29,000 acres as the Benjamin Harrison National Recreation Area. (Braun was scheduled to personally attend the IFA meeting but was forced to stay in Washington due to the threatened government shutdown.)

Click here for a map of the proposed expansion area.

Click here for an article by Steven Higgs on the new legislation.

A half century connecting with the Deam’s wildness

Seven years before Congress established the Deam, I unwittingly shot my first photo of today’s wilderness from the bow of a motorboat captained by my old Eagle Scout buddy Tim Hoffman on a rain-swollen Lake Monroe in May 1975.

Charles C. Deam Wilderness boundary from Lake Monroe, May 1975, Photocopied B&W print | The present-day Deam’s northern boundary provided the backdrop to this photo of a dead tree submerged by a swollen Lake Monroe just off the Peninsula Trail in May 1975.

My 40-year journalistic career informally began in 1980 when my wife said I needed to get out of the apartment and go to a Sierra Club meeting or something. Jeff Stant of the Uplands Group Sierra Club recruited me to become the group’s newsletter editor amid the last phase of the seven-year struggle to establish the Deam Wilderness.

The first of my lifetime of career-oriented public-presentation engagements was a wilderness slideshow celebration titled “A Photographic Journey Through the Deam Wilderness” at a July 1983 Uplands Group meeting in Ballentine Hall on the Indiana University campus.

That presentation and an updated version in April 1984 at the Monroe County Public Library were drawn from 32 rolls of color slides captured during a multipart trek along the then-26-mile (+/-) Hickory Ridge Hiking Trail between April 1982 and June 1985.

The Deam: Indiana’s first federally protected wilderness

The Indiana struggle to establish a protected wilderness on the Hoosier began with the Eastern Wilderness Areas Act of 1975. Congress mandated the U.S. Forest Service identify roadless areas in national forests east of the Mississippi River for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Flier from Charles C. Deam Wilderness Slideshow, July 1983, presented on the Indiana University campus to a monthly meeting of the Uplands Group Sierra Club.

A 15,000-acre Forest Service proposal was countered by an IU-based Indiana Public Interest Research Group (INPIRG) proposal for a 32,000-acre Nebo Ridge Wilderness Area, which included most of today’s Deam and other undisturbed areas like Nebo to the north and east.

Seven years of heated debate between preservationists, landowners, and various other interested groups resulted in the nearly 13,000-acre Deam’s creation on the southeast shore of Lake Monroe in 1982 as Indiana’s first and only federally protected wilderness.

Preservationists failed to achieve permanent wilderness designation for Nebo, Porter Hollow, Bad Hollow, Panther Creek, Browning Mountain, and other wild areas across the Salt Creek Valley on the lake’s north shore. But those backcountry areas did receive improved protection in a historic, 1992 revision of the Hoosier’s management plan that protected 60 percent of the forest from commercial logging.

Named after Indiana’s first state forester, the Deam’s federal wilderness designation means that its timber will never be logged, that roads will never be built, that off-road vehicle trails will never be allowed, that the Deam’s evolution will be left to natural forces — in perpetuity.

Browning Mountain is not protected wilderness, but it is a roadless area just up the Salt Creek Valley in Brown County that would become part of the new wilderness area under pending legislation introduced by U.S. Sen. Mike Braun, with support from the Indiana Forest Alliance. It is within eyeshot of the Hickory Ridge Lookout Tower and was included in some preservationist proposals in the early days of the struggle for an Indiana wilderness.

The Deam region’s unforgiving landscape

Even before Braun’s announcement, the Deam and adjacent wild areas like Nebo made up one of the largest stands of mature, deciduous hardwood forest in Indiana. Its narrow, flat-top ridges and steep, V-shaped creek ravines lie in the Salt Creek Valley in Monroe, Brown, Jackson, and Lawrence counties. The biodiversity website iNaturalist documents more than 300 life forms on the Deam, categorized as animals, fungi, plants, and protozoans.

Grubb Ridge Trail, July 1982, Digitized Kodachrome slide | The Indiana Department of Natural Resources designates the eastern box turtle as a Species of Special Concern in Indiana. Box turtles are long-living, slowly maturing reptiles that produce few offspring and have high mortality rates due to accidents on roads.

Like all the Southern Indiana hills, the Deam’s landscape was formed by thousands of years of Ice Age–melt erosion — not by glaciers stopping at Martinsville. Due to the rugged topography, it was among the last tracts of land in the state to be settled.

Like the rest of the Hoosier National — and most of Southern Indiana’s public forests — the Deam in the 19th century was heavily settled. At the peak, its boundaries hosted a community of some 80 small farms connected by 60 miles of road.

But timber proved to be the unforgiving landscape’s only source of sustenance for the settlers. After ecological devastation wrought by a half century of unsustainable clearcutting, Indiana led the nation in timber production in 1890. The once-abundant deer, turkey, and other wildlife vanished soon thereafter.

The impoverished landowners fled en masse, leaving local counties with drastically shrinking tax rolls and denuded hillsides that eroded into the Salt Creek’s North, Middle, and South Forks. When the federal government offered to buy the impoverished topography for inclusion in the nascent National Forest System, restore the landscape, and develop logging and tourist industries around its natural resources, the state and counties leapt at the opportunity.

The Indiana General Assembly passed legislation in 1935 allowing creation of the Benjamin Harrison National Forest, which became the Hoosier National Forest when it was established in 1951.

From Walden to a popular outdoor destination

The Hoosier National was established the year I was born. My lifelong explorations began 24 years later, when I was two years graduated from IU, three after I got my first 35mm camera.

In 1975, I lived alone with my Nikon and darkroom in a five-room, Walden-esque shack by the Scenic View Restaurant with a lake trail 30 feet from my back door. The kitchen table, with its panoramic, kitchen-window view of Monroe and its magnificent, wooded watershed, sat a half mile from three different Hoosier National boundary lines.

Before the nearly 13,000-acre Deam Wilderness was established, preservationists worried it was too small and at risk of being loved to death. The Deam is located within a 3-hour drive of more than 5 million people in Indianapolis, Louisville, Cincinnati, and Evansville. Pending legislation in Congress would more than double the Deam’s size and add another 29,000 acres of nearby, protected wildlands in a new Benjamin Harrison National Recreation Area.

In that hovel on Knightridge Road, 7.5 miles north of today’s Deam sign at State Road 446 and Tower Ridge Road, I discovered Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and Eliot Porter. There I began living a photographer’s life. A month after the spring 1975 boat trip, Tim, my Irish Setter Shannon, my Nikon, and I backpacked in and camped on the Patton Cave Trail above the cave’s opening.

Those mid-1970s, pre-internet Deam explorations occurred at a time when only a handful of hardcore outdoor lovers knew anything of the area’s unique sylvan beauty and natural composition.

A half century later, more than 40,000 IU students and 5 million-plus people in Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Louisville, and Evansville live between 20 minutes and 2.5 hours from the Deam.

The Hickory Ridge Trail from my younger days has been expanded to 36 miles of marked trails through Terrill Ridge, Grubb Ridge, and Cope Hollow. In spring and fall, the trailhead parking lots overflow onto Tower Ridge Road.

The Hickory Ridge Lookout Tower on the Deam’s border offers one of the most magnificent nature views east of the Mississippi.

Backpack camping is allowed throughout the forest, as is horseback riding.

Loving the Deam to death

In my 2016 IU Press book, A Guide to Natural Areas of Southern Indiana, I echo concerns expressed during the pre-Deam years over the wilderness being “loved to death.” And due to overuse, the Forest Service has indeed been forced to impose some restrictions on its use. Group sizes are limited to ten persons, for example. Camping is limited around trails and water resources. Geocaching is prohibited. So is parking on Tower Ridge Road.

But the Deam is off limits to the Forest Service’s contemporary fixation on clearcutting, burning, and spraying the forest in the name of “ecological restoration,” as evidenced by raging controversies over management plans for Houston South and Buffalo Springs.

Thanks to the vision of Bloomington wilderness advocates like Jeff Stant, Hank Huffman, Al Strickholm, and countless others four decades ago, Indiana’s only protected wilderness will remain safe from the chainsaws, drip torches, and herbicide sprayers and available 24/7 for nature lovers to explore and enjoy.

And now, after a four-decade-plus career advocating for Indiana wildness, Jeff Stant and Indiana’s passionate corps of forest defenders have revived the dream of an expanded wilderness in the Hoosier National.

And not only is Nebo Ridge now proposed for wilderness designation, but an area almost twice the size of the original 1970s-era INPIRG proposal would be managed to protect water quality, recreation, and other natural values.

Forty-one years was a long wait, but the Deam now could become what it always should have been.

Books by Steven Higgs

Books by Bloomington-based writer and photographer Steven Higgs include “A Guide to Natural Areas of Southern Indiana” (2016) and “A Guide to Natural Areas of Northern Indiana” (2019), available at IU Press.

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024

![[Photo Gallery: 20 photos]: Legislation recently introduced by Sen. Mike Braun would double the size of the Charles C. Deam Wilderness Area by Lake Monroe and convert another 29,000 acres of Hoosier National Forest into the Benjamin Harrison National Recreation Area. This photo was taken from the Hickory Ridge Lookout Tower, which stands 133 steps above the Deam’s Terrill Ridge, a thousand feet above sea level. Built in 1939 to identify forest fires, the tower is a popular destination due to its magnificent 360-degree view of the Southern Indiana forest. | All photography in the gallery above by Steven Higgs](https://limestonepostmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/feature-1-1.jpeg)