[Editor’s note: This is part 2 of a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post. You can read more about the collaboration at the end of this article. In part 1, published in February, Steve Hinnefeld reported on housing problems in Monroe County. Below, he looks at the various initiatives by housing advocates and officials to address those problems.]

[Editor’s note: This is part 2 of a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post. You can read more about the collaboration at the end of this article. In part 1, published in February, Steve Hinnefeld reported on housing problems in Monroe County. Below, he looks at the various initiatives by housing advocates and officials to address those problems.]

Jolene and Cornelius Wright hoped to buy a house in Bloomington where they could enjoy retirement, but it wasn’t looking promising. Semiretired and working part time, they couldn’t find anything that matched their budget.

“Trying to find housing wasn’t the problem. Trying to find affordable housing was huge,” Cornelius says, echoing a common complaint about the high-priced local real estate market.

Then a friend suggested they look into Habitat for Humanity. They knew about the organization but thought they wouldn’t qualify. But they applied, were accepted, and began work on their required 250 hours each of “sweat equity” building homes with others.

Later this month, work will start on their two-bedroom, one-bath house. It’s adjacent to RCA Community Park, in the 69-unit Osage Place neighborhood that Habitat is developing on the city’s south side.

“We’re very excited,” Jolene says. “When we got our lot offer, we went out there and took our picture: our first picture where the Habitat house will be.”

Founded in 1988, Habitat for Humanity of Monroe County has built more than 220 homes and housed more than 815 people, more than half of them children. It keeps its simple but high-quality homes affordable by relying on volunteer labor and donated materials and land, and by providing generous mortgages. New Habitat homes have been selling for around $200,000, compared to the area median price of $275,000.

Workers build a house in the Osage Place neighborhood, adjacent to RCA Community Park. Since 1988, Habitat for Humanity of Monroe County has built more than 220 homes and housed more than 815 people, more than half of them children. | Photo by Jim Krause

For people who can put in the required time and labor and can afford modest loan payments, Habitat provides a welcome path to home ownership. But it’s only a small part of what’s needed to meet the need for affordable housing in Monroe County.

“There’s not a silver bullet,” says Habitat Executive Director Wendi Goodlett. “It’s going to take lot of different angles to chip away at this huge problem that we’ve created.”

Fortunately, other angles are being pursued. A community land trust will take a new approach to home ownership. The city-driven Hopewell project, at the former IU Health Bloomington Hospital site, will add up to 1,000 housing units, many of them affordable. Zoning incentives for developers are creating hundreds of affordable and medium-priced rental units.

Two realities

But housing costs in Bloomington and Monroe County remain among the highest in Indiana. Citizens differ on how to promote affordability, with development plans generating heated debate. Advocates and employers say there’s a clear need for more housing, but not everyone sees it.

“There is this sense that we’re living in two realities,” says Mary Morgan, director of housing security for Heading Home of South Central Indiana, a regional initiative to address homelessness. “And I don’t know how we get past that.”

Work will start soon on Cornelius and Jolene Wright’s new home in the Osage Place neighborhood. | Photo by Jim Krause

The Wrights have seen the challenges firsthand. Cornelius, 68, and Jolene, 70, met in the San Francisco area and married 40 years ago. With young children, they left California, in part because of high housing costs, and moved to Jolene’s native Bloomington.

Cornelius worked for the IU Alumni Association, and she worked for Head Start and later for the Monroe County Community School Corporation. They owned a house but sold it — “a big mistake,” he says. They separated briefly, reunited, and moved into a mobile home, thinking it would be affordable. But lot fees kept rising, and the mobile home park hasn’t felt like a community.

With his income from working part time at Boys & Girls Clubs of Bloomington and hers as coordinator of the Area 10 Agency on Aging’s Endwright East senior center at College Mall, they will be able to manage payments for their zero-interest mortgage. And they have enjoyed working on other Habitat houses.

“I think it’s exciting,” Jolene says, “working on building a house and learning how to do those things. I’ve done framing and siding and a lot of that. I’ve learned a lot.”

They also recognize many people their age struggle to find housing they can afford. “At Area 10, people come in all the time, and they ask about housing: ‘Where’s the affordable housing for seniors?’” Jolene says. “And there really are very few options.”

Holding land in trust

In a land trust, “the homeowner is just buying the home, not the land,” says Nathan Ferreira, director of real estate development at the Bloomington Housing Authority. Ferreira is shown here at a land trust established by Summit Hill Community Development Corp., a nonprofit created by the housing authority. | Photo by Jim Krause

Options could be coming via a land trust established by Summit Hill Community Development Corp., a nonprofit created by the Bloomington Housing Authority.

“Essentially, we’re opening home ownership to a whole part of the population that otherwise may not be able to afford a home because prices are so high,” says Nathan Ferreira, director of real estate development at the housing authority.

In a land trust project, the homebuyer can own the house, but the trust will own the property that it’s built on. In the case of a $200,000 home where the land is 20 percent of the value, “the homeowner is just buying the home, not the land, so their price is $160,000,” Ferreira says.

If the house increases in value and is resold, the land trust gains the appreciation of the land price and uses it to keep the home affordable for its next owner. The land trust will use 99-year ground leases or restrictive deed covenants to ensure that future sales are to low-income households.

Summit Hill’s first housing project will be developing 45 single-family homes on Bloomington’s north side. It’s adjacent to Atlas on 17th, a new student-oriented apartment development with streets named for Colorado ski resorts. Lafayette, Indiana-based developer Trinitas Ventures donated the “build-ready” lots, with streets and utilities provided, on 7.5 acres, as a condition of zoning approval.

Ferreira says some of the homes will be built by Habitat for Humanity, using its volunteer-labor model, and some by Clear Creek Homes, a Bloomington builder of affordable modular homes. Buyers will have to meet income qualifications and complete homeowner classes offered by Habitat or the Bloomington Housing and Neighborhood Development department.

“We hope to have builders here and break ground by April,” Ferreira says, looking across the property while a grader shifts soil into a suitable contour.

Supply, subsidies, and incentives

Mayor John Hamilton says creating more affordable housing has been a priority since he took office seven years ago. Bloomington is one of the most expensive housing markets in the state, he notes. As housing prices rise, many people struggle to be able to afford to live in the city.

Mayor John Hamilton says creating more affordable housing has been a priority since he took office seven years ago. | Courtesy photo

“If we lose the ability for teachers, public employees, our basic work force, middle class folks … if they can’t live in the city, it’s really damaging, I think,” he says.

He doesn’t want Bloomington to go the way of coastal cities where housing prices are out of reach. Cities like San Francisco and New York may look successful, he says, “but they’re not. They don’t work for so many people who work in the city and want to be in the city and get priced out.”

Hamilton says there are two paths to affordability: supply and subsidies. “Those are both important,” he says. “If you try to do one without the other, you’re not going to be successful.”

City records show the housing supply has grown by more than 5,600 units since 2016. Many of those have been high-end student apartments, but the number also includes about 1,400 affordable units, Hamilton says.

Affordable for whom? The term means a household won’t spend more than 30 percent of its after-tax income on housing. Some affordable units are set aside for low-income households that make less than 80 percent of the area median income, which is about $85,000 for a four-person household. Some are for very low-income households that make less than half the area median income. Others are “workforce housing” for those who make between 80 and 120 percent of the median.

Bloomington leverages affordability with zoning incentives. Developers can get a break on zoning — a little more density or an extra floor on an apartment building — if they include affordable units or contribute to the city’s affordable housing fund. The fund has collected about $4 million and dispensed about $1.5 million in grants and loans since 2017 to help pay for low-income housing and infrastructure.

The 45 lots donated for the land trust project are one example. Another is the 100-unit Annex apartments at 3rd and Grant streets, where 15 percent of units are designated low-income or workforce housing. Trinitas’s Latimer Square apartments at the former east-side K-mart site doesn’t include affordable units but replaces an empty store and vacant parking lot with housing and some green space.

Hamilton says it’s inevitable that Bloomington and the surrounding area will keep growing and will need more housing. “Our area will grow,” he says. “Crane [naval center], jobs, IU. A dynamic economy will be attractive, and we have a wonderful quality of life. People want to live here.”

Fifteen percent of the 100-unit Annex apartments, which are still under construction at East 3rd and South Grant streets, are designated low-income or workforce housing. | Limestone Post

Incentives for landlords

In addition to zoning incentives, some developers get subsidies for building affordable housing through the competitive low-income housing tax credit program. There are also subsidies for renters, via the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) housing choice voucher program.

But the waiting list for rental vouchers is long, and getting one is no guarantee of finding housing. The Bloomington Housing Authority, which runs the program, says many landlords don’t accept vouchers. They may think low-income renters are risky, or they may worry about HUD regulations.

To help, the housing authority has created a landlord risk mitigation fund, starting with more than $300,000 from several sources, including city and county government. It will reimburse landlords up to $2,000 in costs they incur from renting to low-income tenants, such as property damage and missed rent. Up to 160 low-income renters can be covered by the program, says Leon Gordon, the housing authority’s administrative director.

“We’re getting ready to implement it,” Gordon says. “We’re doing outreach now to community partners and landlords to explain how the program works. Then we will begin inviting renters.”

Housing advocates say it’s crucial to recognize the role that landlords and property managers play in providing safe, affordable housing. Heading Home of South Central Indiana is working on a video to promote the program.

“We need to do a better job of supporting landlords, and there are some good landlords out there,” says Morgan with Heading Home.

A landlord-friendly legislature

Indiana laws, however, are notoriously friendly to landlords. Indiana is one of only five states where tenants can’t withhold rent to force necessary repairs. The state’s eviction rates are some of the highest in the U.S.

Indiana is one of only five states where tenants can’t withhold rent to force necessary repairs. State Senator Fady Qaddoura has written legislation to change that but legislators have kept it from passing. | Courtesy photo

In 2022 and again this year, Sen. Fady Qaddoura, D-Indianapolis, authored legislation to strengthen tenants’ rights, but Republicans kept it from passing as written, both times. A law approved in 2021, over the veto of Gov. Eric Holcomb, pre-empts local ordinances that regulate landlord-tenant relations.

“It is a long-held principle in the Indiana Statehouse that we don’t do anything around housing,” Rabbi Aaron Spiegel of the Greater Indianapolis Multifaith Alliance recently told WFYI.

Lawmakers did convene a task force on housing issues last year, and it recommended a range of policies aimed at boosting home-building. One suggestion, for a state-run revolving loan program to help communities fund infrastructure for housing development, became legislation that has been approved by the House and sent to the Senate. But legislators haven’t yet decided on funding for the program. Also, 70 percent of the loans would have to go cities with fewer than 50,000 people. Ellettsville could qualify, but Bloomington and Monroe County would compete with large cities for the other 30 percent.

A potentially helpful measure, creating a new 50 percent state tax credit for contributions to affordable housing organizations, was approved by the Senate and sent to the House, where it was assigned to the Ways and Means Committee and is awaiting a hearing.

“That would be huge for us,” says Goodlett, the Habitat for Humanity director. “If somebody got a 50 percent tax credit? It would be a great incentive for them to support affordable housing.”

But Hamilton, the Bloomington mayor, isn’t optimistic about help from the state. “We have to chart our own destiny,” he says. “We have the capacity to do it.”

High hopes for Hopewell

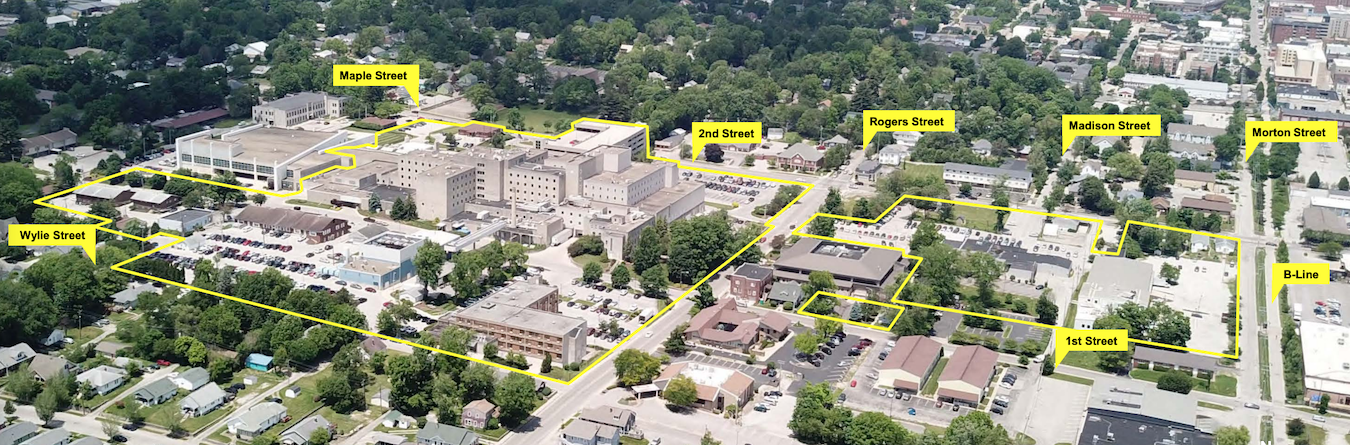

Artist renderings of the Hopewell project, as included in the Bloomington Hospital Redevelopment Master Plan Report, January 2021. Hopewell will be developed on the former site of IU Health Bloomington Hospital.

The most ambitious government-driven housing initiative in Bloomington is the planned conversion of the former site of the IU Health Bloomington Hospital to a new community called Hopewell.

The city announced in 2018 that it would buy the 24-acre property for $6.5 million. With an attractive location near downtown and adjacent to the B-Line Trail, it will be developed with up to 1,000 housing units and some commercial and retail properties. The plan is that many will be affordable rentals or owner-occupied homes.

“The big decision we made about Hopewell was to buy the land,” Hamilton says. “That’s a huge opportunity for us to have control over what happens.”

In addition, the city will spend millions of dollars installing roads, utilities, and other infrastructure. A $1.8 million grant under Indiana’s Regional Economic Acceleration and Development Initiative will help pay for street construction. A 2020 master plan for the site, created by the architecture and planning firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill after multiple community-input sessions, envisions a mix of commercial space and housing types, an east-west greenway, a new street grid and ample public space.

According to the plan, the site will include some single-family houses and town homes, but most of the housing will be multifamily. It describes a range of about 600 to 1,000 housing units, including hundreds of units of workforce housing and others for lower-income residents.

“We’re very focused on affordability,” Hamilton says. “How do we have the full mix, the full range of people living at Hopewell, from market-rate to low-income housing tax credits?”

Making and keeping the housing affordable may be challenging, given the appeal of the location and its amenities. Hamilton says affordability can be maintained with lease agreements and deed restrictions.

“It’s a deep belief of mine that once we get an affordable unit, don’t lose it,” he says.

Hamilton says the city’s initial ownership of Hopewell will let it guide development to benefit the public. It can insist on sustainable design features, attractive and high-quality buildings, substantial green space, and more. But not everyone is a fan of the city’s role.

“I would rather have it be done by the private market,” says Mark Figg, co-owner of Kirkwood Property Management and a former board member of the Monroe County Apartment Association. “It would be faster and less expensive. The Hamilton administration has decided to be a developer, and I’m not a proponent of that.”

Looking north at the former Bloomington Hospital site, where the Hopewell project is to be developed. | Source: Bloomington Hospital Redevelopment Master Plan Report, January 2021

Missing in the middle

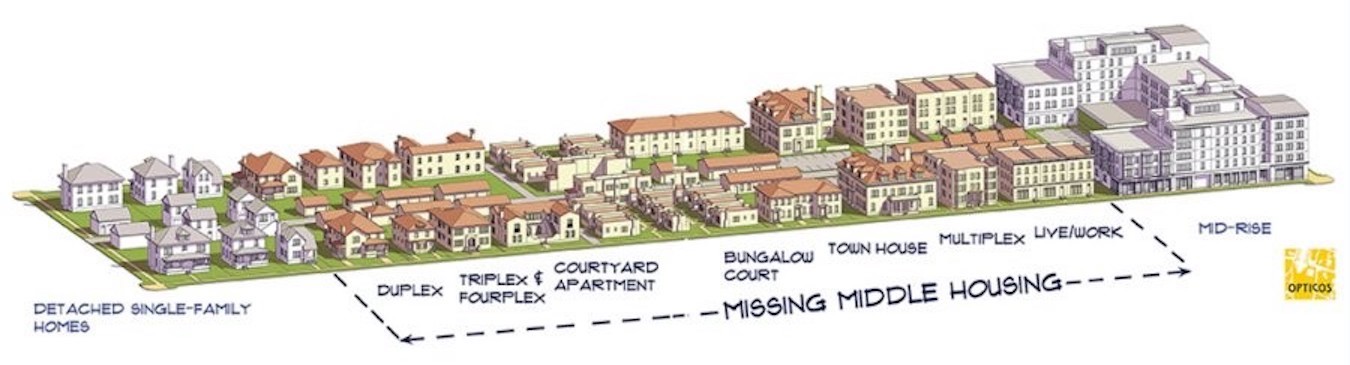

One way to get more housing is to change zoning rules to allow duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes in neighborhoods of single-family homes — what planners call missing middle housing.

But when the Hamilton administration suggested more such density in a revision of Bloomington’s Unified Development Ordinance, there was a prompt reaction. Signs popped up across the city: “Mayor Hamilton, we didn’t elect you to destroy our neighborhoods.”

Ultimately, in 2021, the city council voted to allow duplexes in single-family zones, but with limits: They would require conditional use permits from the planning department, no more than 15 per year could be approved, and they couldn’t be closer to each other than 150 feet.

Deborah Myerson, a planning consultant and housing advocate, says a lot of different tactics are needed to address the housing problem, “and not any one thing is going to do what’s needed.” | Courtesy photo

Hamilton argues that adding duplexes will make housing more affordable. If two units can occupy one lot, it only makes sense that each can cost less, he says. But critics insist it will drive up real estate costs because a developer or investor can make more money by turning a lot or house into two rentals.

Deborah Myerson, a planning consultant and housing advocate, is a fan of missing middle housing but doesn’t see it as the only solution to local housing problems. “There’s a lot of different tactics we need, and not any one thing is going to do what’s needed,” she says.

Some opponents of duplexes suggested they would be occupied by college students whose lifestyle would detract from neighborhood qualities. Myerson isn’t swayed.

“One, students live in our community and not all students have a wealthy family,” she says. “It’s important to recognize there are students with housing needs. Two, some of the quality-of-life issues that come up, they’re not about if it’s a rental, but are we enforcing noise control, are we enforcing trash?”

Myerson argues that well-designed duplexes can fit seamlessly into single-family neighborhoods, including near downtown and the IU campus, and she grounds her argument in themes of equity and inclusiveness. Prices may go up, she says, “but it’s not because duplexes are going in. It’s because there’s some prime real estate that’s close to where people want to live. And I don’t think only people who can afford single family homes ought to be able to live in those neighborhoods.”

It’s been nearly two years since city code was changed to allow duplexes in single-family zones. Through 2022, the city had received four requests for duplex permits. Only one has been approved.

“This is not exclusively about missing middle, but what kind of housing do we need and why, and what can we agree on?” Myerson says. “That’s a point of contention right now.”

“Missing Middle Housing” represents the middle scale of buildings between single-family homes and large apartment or condo buildings. Many housing advocates say that allowing duplexes in single-family zones can make housing more affordable in a community, but the debate has been contentious. | Illustration courtesy Opticos Design

Too dense for the county

What kind of housing is needed is a point of contention not just in the city. Tom Wininger, a third-generation local builder, says he was ready to start work on 95 detached single-family homes south of Bloomington when a county official suggested he look into building affordable workforce housing. “That put the idea in my head,” he says.

Working with an architect, he converted the proposal, called Southern Meadows, to a plan for 190 owner-occupied, paired patio homes on the same site, using mostly the same housing footprint. “At the time, I thought I could sell each side for under $250,000,” he says.

In March at the Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce’s Governor’s Luncheon, Cook Group President Pete Yonkman said he was stunned during a 2021 Monroe County Plan Commission hearing when some people suggested there’s no lack of housing in the community. | Photo by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian

He lined up letters of support from business officials, including leaders at the Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce and the Bloomington Economic Development Corp. Pete Yonkman, president of Cook Group and Cook Medical, spoke in favor at a public hearing in April 2021.

The Monroe County Plan Commission voted 5–4 for the plan, but the county commissioners rejected it, reasoning it was too dense for the county. They also turned down two other proposals for housing in the same area after sometimes contentious hearings and debates.

“It’s like getting hit in the head,” Wininger says. “I thought I was doing it — I know I was doing it — for all the right reasons.”

Commissioner President Penny Githens said in an interview with WFHB News that county officials felt an obligation to people who had bought or built houses in less developed areas.

“People want to live in less congested areas, so they have bought a home or a farm in a non-urban part of the county,” she says. “They chose that. Are we going to deprive them of that by pushing development out further and further?”

She adds that homes are, in fact, being built in Monroe County and outside of Bloomington, especially in the Ellettsville area. But she says too much development could be harmful, causing flooding, stressing roads and infrastructure, and straining the capacity of Lake Monroe to provide water.

“I personally, and this is just me, I don’t want to see unchecked growth,” she says. “I’m not anti-growth. … But I think we have to be very careful about what we do with our growth.”

Wininger went back to the previous plan of building single-family, detached houses. And they are selling, sometimes for over $500,000. He’s also building affordable paired homes, but not in Monroe County. They are in southern Greene County, near the Naval Surface Warfare Center at Crane and an $84 million microelectronics campus being built at the WestGate@Crane Technology Park.

Yonkman suggested the commissioners’ rejection of Wininger’s paired-homes plan was a missed opportunity to provide affordable housing, which Cook Group employees identify as a top priority. At a Chamber of Commerce luncheon in March 2023, Yonkman said he was stunned, at the plan commission hearing in 2021, when some people suggested there’s no lack of housing, that it’s “a myth perpetrated by the Realtors.”

“How can we expect to deal with the real needs of our community if we, as leaders, can’t even agree on what the needs are?” he said.

Building for zero homelessness

Bloomington and Monroe County officials often disagree, but both city and county provide financial support for access to housing. Both have supported Habitat for Humanity and New Hope for Families, which provides shelter and services for families facing housing insecurity. And they joined forces in late 2021 to commit $5 million for Heading Home of South Central Indiana.

Heading Home grew out of a working group on homelessness convened by United Way of Monroe County and the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. From the start, it has focused on housing as a key factor for making homelessness “rare, brief and nonrecurring.”

Mary Morgan, director of housing security for Heading Home of South Central Indiana, says the group is focused on making homelessness “rare, brief and nonrecurring.” | Photo by Jim Krause

“What Heading Home has acknowledged is, there needs to be a focus on the entirety of the system and on the region,” says Morgan, director of housing security for Heading Home. She says there are many reasons that people become homeless, but a key factor is that they can’t find housing that they qualify for and can afford.

Heading Home embraces a philosophy called Housing First. “It’s not housing only,” Morgan says, “but it’s recognizing the primacy of housing in relation to health care, mental health, substance abuse, and all the other issues that it’s hard to address if you don’t know where you’re staying.”

The small Heading Home staff have been busy. They became the first group in Indiana to join Built for Zero, a national coalition working to end homelessness. They’ve focused intently on helping homeless veterans, worked on a resource for finding rental homes, and produced public engagement tools.

“But honestly, I think lot of what we’re doing is relationship building,” Morgan says, “both within the Monroe County area but, more importantly, within the region.”

Heading Home serves Monroe and five surrounding counties, and it has made connections and collaborated with service agencies and shelters in Bedford, Martinsville, and Greene County, where housing may be less expensive but services for unhoused people are sparse.

Collaboration and celebration

In Monroe County, Morgan says, there often seem to be competing visions of what the community needs. “Some people want a Bloomington and Monroe County as it was two decades ago, not the way it is now,” she says. “We are not going to be able to flip a switch and go back to a nostalgic Bloomington.”

But she is optimistic about the collaboration taking place around housing — across different counties and among public officials, nonprofit organizations, social service agencies and advocates — and by the difficult and even heroic work that organizations and individuals are doing to keep people housed.

“We’ve gotten better at celebrating the work that’s been done,” Morgan says, especially work done by people working on homelessness and directly helping residents who are unhoused. “Because, honestly, for people who are frontline workers, it’s really hard.”

Cornelius and Jolene Wright. | Photo by Jim Krause

Creating policies and programs that promote affordable housing can be hard, too. Yet there’s a lot being done: a thriving Habitat organization, a new land trust, efforts to make the most of zoning incentives and housing subsidies, the first glimmer of the new Hopewell neighborhood, and more.

Maybe that’s something to celebrate as well. Certainly, we can welcome progress when families and individuals find a safe and stable place to live. All the more so when it’s their own home.

For Jolene and Cornelius Wright, looking forward to starting work on their own Habitat house as they build homes with other families, the experience is about more than having a roof over their heads. It’s also about being part of a community.

“We have that wonderful opportunity,” Cornelius says, “as our home is being built, to meet and interact with our neighbors before we ever become neighbors.”

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

Limestone Post article by by Brookelyn Lambright, Karl Templeton, and Brenna Polovina from the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism, published August 1, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

WFHB reports:

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 1), August 7, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 2), August 14, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 3), August 21, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 4), August 28, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, photography by Benedict Jones, published September 24, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

WFHB reports:

- Apprenticeships (Part 1), October 9, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 2), October 16, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 3), October 30, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

Limestone Post article by Haley Miller, published November 26, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

WFHB reports:

- Police and Social Work, January 29, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 2), February 5, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 3), February 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

Limestone Post article by Marjorie Hershey, photos by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian, published January 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

WFHB reports:

- Political Polarization, (Part 1), March 19, 2025

- Political Polarization, (Part 2), March 27, 2025

- Political Polarization, (Part 3), April 2, 2025

Mental Health Issues Are Increasing Dramatically Among Hoosier Youth

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, photography by Benedict Jones, published April 3, 2025

Mental Health Issues Are Increasing Dramatically Among Hoosier Youth

WFHB reports: