Editor’s note: This article is part of the journalism collaboration “Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate.” Read more about this award-winning series at the end of this article.

It didn’t get as much press as Time’s “Person of the Year” selection of Donald Trump. But when Merriam-Webster Dictionary’s publisher chose “polarization” as the 2024 “word of the year,” he underscored a political issue that bedevils Bloomingtonians every day.

Party and ideological polarization is the tendency for each party and its supporters to become less diverse internally and more different from the views and social characteristics of the other party. So in recent decades we have seen the Democratic Party become more consistently liberal and moderate in its policies and the Republicans more consistently conservative to very conservative. In the mid-1900s, if someone told you that she was conservative, you probably wouldn’t be able to guess whether she considered herself to be a Republican or a Democrat; there were conservative Democrats (many of them here in Indiana) and liberal Republicans. Now, the policy differences between the two parties are much greater, and a “liberal Republican” is as likely to be found as a pig with wings.

At the same time, communities have become increasingly dominated by one party. In practice, this means that we get treated differently by our government depending on which party controls the community we live in. As various counties and even states become more homogeneously Democratic or Republican, their citizens cope with ever more left-wing or right-wing policies. Here in Monroe County, we get whiplash; Bloomington has become an ever-bluer enclave in the red sea of Indiana. So our city government produces liberal answers to political questions at the same time as our state government hands us more right-wing answers.

The Bloomington city council doesn’t just have a Democratic supermajority; it has no Republican members at all. Republicans are so accustomed to losing city council and mayoral elections that they find it hard even to recruit candidates. Yet in the Indiana state government, there is a Republican trifecta: the governor and a majority of both houses of the state legislature are Republican. In fact, Republican legislators have a supermajority, so the Democratic minority has almost no voice in legislating.

Inflaming strong emotions

What has caused this polarization? There are two main culprits and several other guilty parties. First, beginning half a century ago when national Republicans successfully wooed conservative white Southerners away from their traditional Democratic roots, by overturning the longtime Republican support for Blacks’ civil rights, both parties became more internally consistent in their views. The Democrats, long a mixture of strange bedfellows including conservative white southerners, urban workers, white ethnics, and Blacks and Latinos, thereby lost their conservative wing; that made the Democratic Party more consistently liberal and moderate. In turn, once those conservative white southerners switched parties, the Republicans became more consistently conservative and more committed to emphasizing so-called traditional values: opposition to gay rights, abortion, diversity initiatives, and “woke” policies. These anti-“woke,” anti-minority appeals helped Republicans cut into the traditional Democratic voting patterns of white ethnics and other urban workers.

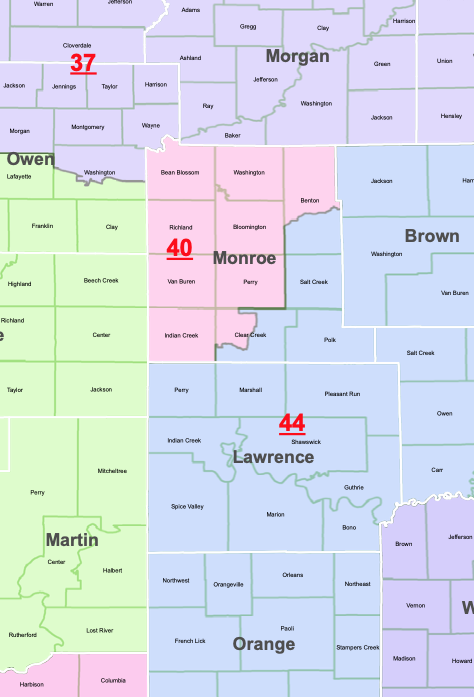

Gerrymandering has allowed Indiana Republican candidates to win about 80 percent of the state’s Senate seats by getting only about 58 percent of the state’s votes. Above, the Indiana Senate District map for south-central Indiana. | Source: Indiana General Assembly website

That shift in the parties’ coalitions was further entrenched by sophisticated gerrymandering methods. Increasingly one-party state legislatures used computer programs to rig the redrawing of legislative district lines. The party in power was now able to eke out the maximum number of state legislative and congressional districts that were winnable for their party. For example, in Indiana, although statewide Republican candidates typically win about 58 percent of the state’s votes (suggesting that state voters are about 58 percent Republican), about 80 percent of the state’s Senate seats are held by Republicans. That’s a level of gerrymandering that early U.S. politicians couldn’t have imagined in their wildest dreams.

Political scientists find that this polarization is accompanied by growing partisan hostility — called “affective” or “negative partisanship.” So we find in surveys that almost half of respondents say they wouldn’t date someone of the opposite political party, and even more say that the other party’s policies are a threat to the nation’s well-being. In a recent survey, three quarters of Republicans and 63 percent of Democrats said they consider members of the other party to be more immoral and dishonest than other Americans.

Inevitably, some political candidates learn that they can profit from further inflaming these strong emotions. Whenever anxiety levels mount, such as during the “Red Scare” at the end of World War I and the “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion” slogan of the early 1900s, some will seize the chance to demagogue and scapegoat some less-powerful segment of the population — and feel morally righteous in doing so. We are in the midst of widespread anxiety now: terrorism, a pandemic that has killed more than a million Americans, rapid social change, and the rise of social media in which algorithms steer users toward insult, outrage, and controversy in order to increase customer involvement.

Serious consequences of polarization

The resulting polarization makes life harder for our local election officials. They hear about election workers in various areas being publicly vilified and having their families threatened. In September, for instance, secretaries of state (the officials who oversee state elections) in at least six states received packages containing suspicious substances; the return address was the “US Traitor Elimination Army,” referring to the false claim that voter fraud was widespread in the 2020 election.

Nicole Browne, Monroe County clerk, counts provisional ballots at the Monroe County Election Board on November 18, 2022, in Bloomington. | Photo by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian

Nicole Browne, Monroe County clerk in charge of administering county elections, notes that it’s much harder to recruit volunteers under these circumstances. “Clerks and other election officials already struggle to recruit and retain quality workers when it comes to elections,” she says. “Polarization certainly doesn’t help.” She states with relief that “it is now a felony [in Indiana] to interfere with or intimidate a poll worker during elections. [But] it is unfortunate that this type of legislation is increasingly necessary, and I can certainly see it being directly attributed to polarized politics.”

Other groups working to ensure that elections are free and fair have similar frustrations. Debora Shaw, co-chair of the Voter Service Committee, League of Women Voters–Bloomington Monroe County, says that even the nonpartisan League has become tarred as partisan in this polarized atmosphere. Although in 2020, two-thirds of local Republican candidates responded to the League’s Voter Guide, telling prospective voters what they planned to do if elected, not a single Republican responded in 2024. Despite the League’s efforts to reach out to local Republicans, partisan distrust has prevailed. “I remember a time when candidates wanted to get their views out to as many potential voters as possible, so this choice to avoid communicating seems odd,” Shaw says. “Whether it results from partisan mistrust or the confidence of running unopposed, candidates who pass up opportunities to inform voters do them a disservice. As a community, we are deprived when decisions about our future are made with less information.”

[Editor’s note: On Saturday, January 25, the League of Women Voters is hosting a legislative update with Indiana Legislators. Go to the end of this article to see the League of Women Voters press release.]

Local party leaders and activists face the same dilemma. William Ellis, Monroe County Republican Party chair, states, “I do feel that it’s made my job harder as chair to get good candidates recruited and elected. Candidates, within Bloomington, are difficult to find because as soon as they say, ‘I’m running as a Republican,’ the first thing they have to do is answer [voters’] questions about Trump, it seems. It makes the job of talking about local issues harder.”

William Ellis, Monroe County Republican Party chair | Photo by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian for Limestone Post

That leaves the minority party in this and other areas less capable of speaking for the people it represents. Because Republicans have such a limited presence in Bloomington, fewer Republicans come to the polls because they feel their voice isn’t being heard, which produces fewer elected Republicans. Ellis notes that “Republicans are just not getting out to vote [in Monroe County] no matter what is done. In 2022 we had approximately 13,000 Republicans not vote. In 2024 it was 11,000. In 2024, this was in spite of door-knocking, thousands of calls being made, a mailer, etc. I am not 100 percent [sure] why Republicans aren’t voting, but I do have to think the polarization plays a part of it. As for talking about political issues, it’s almost impossible to do so without recriminations of some sort.”

The consequences of this polarization for you and me range from humorous to downright terrifying. Poll takers find, for instance, that a change in the party controlling the White House can even result in 180-degree shifts in feelings about how well the nation is doing economically. Many poll respondents — primarily Democrats — who said the economy was doing fine in 2016 discovered a few months later, after Donald Trump’s first election, that the same economy was doing poorly; a number of other respondents — mainly Republicans — who rated the economy as in dire straits in October 2024 suddenly found it to be very good just a month later, once Trump was reelected.

Other types of effects can be more serious. Even as straightforward a matter as the benefits of vaccines — one of the most important public health advances of the past century — has become fodder for partisan discord. Now that the memory of thousands of children and adults living their foreshortened lives in iron lungs has faded, we see increasing numbers of parents delaying vaccinating their kids against dread diseases such as polio, typhoid fever, and measles. So these long-vanquished scourges gain a new chance at life due to misinformation and confusion, caused in part by a desire for partisan gain.

“

Some political candidates will seize the chance to demagogue and scapegoat some less-powerful segment of the population — and feel morally righteous in doing so.

”

Because of polarization, some politicians are able to convince voters that some largely symbolic issues are genuine threats. Consider the “issue” of transgender individuals, in which some politicians evoke the image of hulking adolescent boys claiming to be girls to accost vulnerable young women in school bathrooms, rather than the tiny numbers of young people (estimates are that transgender individuals constitute half of one percent of the population) who deal with frequent bullying. From there, state legislatures can spend weeks riling up constituents about a symbolic threat, instead of addressing declining roads and bridges, needy educational systems, inadequately distributed health care, and rising prices.

Accepting that other views exist: ‘feel, felt, find’

Polarization is a community problem, and it demands a community solution. But the increase in partisan conflict has led many people to turn away from political activity altogether. Although voter turnout rates have increased, the recent “peak” in the 2020 presidential election voting was a paltry 67 percent. One in every three eligible Americans chooses not to get involved. Many Americans tune out political news because it has become so toxic to them. Yet it’s generally true that when the range of people involved in decisions widens, we get better decisions — and certainly more representative decisions — than those made by a few.

Debora Shaw, co-chair of the Voter Service Committee, League of Women Voters–Bloomington Monroe County | Photo by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian for Limestone Post

Disagreement is not the problem. Disagreement is inevitable in a democracy. As the major influence on the U.S. Constitution, James Madison pointed out people’s socioeconomic differences are a primary cause of differences in opinion. We may agree on very broad goals such as the need for a first-rate education system, but we don’t agree on whether we get there by raising teachers’ pay or by posting the Ten Commandments in classrooms, by strengthening teachers’ unions or by pulling books about gender and racial diversity from school libraries. Maintaining a democracy requires us to accept that other views exist that should be treated with respect.

It’s hard to maintain mutual respect when some Americans see other Americans as the spawn of the devil. When negotiation and compromise are seen as signs of weakness, then solving real-world problems becomes almost impossible. It helps to keep this in mind: Anyone who thinks that settling for half a loaf is a bad idea has never gone hungry.

Polarization is not all bad. In small doses, it gives us a shortcut for making the hard choices inevitable in any election. But writ large and combined with negative partisanship, it threatens to distort hard but manageable issues into battles of good versus evil. That’s not healthy for a democratic nation.

But there are alternatives. It’s harder to view “liberals” or “conservatives” as the spawn of the devil when you work individually with one of them on a community project or know them as a neighbor or a co-worker or a colleague in the local parent-teacher organization. Interpersonal contacts that focus on broader benefits go a long way toward humanizing people who would otherwise be the “other side.”

“

Because of polarization, some politicians are able to convince voters that some largely symbolic issues are genuine threats.

”

Here’s a way for you to reduce polarization one individual at a time. I learned it from a local political consultant, Tom Hirons, who described it as “feel, felt, find.” First, acknowledging that “I know how you feel” can establish a more sincere connection with the other person, without raising his or her defenses. Then: “I’ve felt that way myself at times.” Again, you create a link with the other person, helping them understand that you don’t consider them weird or ridiculous. Finally, “But I find that ….” Here’s where you present an alternative view of the other person’s concern, one that refers to your own experience and offers factual evidence that there’s another way of looking at the same concern.

Rachel Wahl writes in “Why you should talk to people you disagree with about politics” (The Conversation, December 3, 2024) that “… people rarely change their minds about political issues as a direct result of these discussions. But they frequently feel much better about the people with whom they disagree. When people sense that others are sincerely curious about what they think, asking calmly posed, respectful questions, they tend to drop their defenses. Instead of being argumentative in response to an aggressive question, they try to mirror the sincerity they perceive.” By asking why someone voted the way they did or why they feel the way they do about vaccines or transgender people, you become “more relatable, and often [your] intentions are revealed to be well-meaning — or even ethically sound.”

Not only can you offer them a different way of thinking about an issue, but you can also come to understand how their view could make sense, given their circumstances. In other words, don’t expect to change someone else’s mind. But in encouraging the other person to think about why he or she holds that view, and that a relatable person such as you can hold a different perspective, it’s possible that you may lead him or her to reexamine the issue.

Susan Davis, Democratic canvasser | Photo by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian for Limestone Post

These well-intentioned personal contacts are exactly what’s needed to help us see political opponents as people, not as enemies. For example, Susan Davis, who with her husband, Doug, canvassed for Democratic candidates in their Monroe County precinct prior to the 2024 election, delivered party literature to more than 400 homes. They focused on families likely to lean Democratic but met non-Democrats as well. Susan reports, “We only encountered three hostile owners. One said he hated Democrats. One just gently shut the door in my face. One ordered me off his property. But the overwhelming majority of Republicans were courteous when I asked if they were interested in receiving Democrat campaign literature.”

This suggests that polarization isn’t inevitable, even now. Ellis, too, tries to reduce the polarization by working with the group Braver Angels, set up to bridge the partisan divide and encourage greater civic trust.

Democracy is hard. It’s natural for us to assume that what tops our own personal agenda ought to top everyone else’s as well; if I believe that rescuing animals from shelters takes priority over other issues, then it’s natural to assume that mine is the correct view, that it’s widely shared, and that anyone who prefers to buy at pet stores is morally compromised.

Natural, but unlikely to lead to the kind of calm political discussion needed in a nation where there are almost 340 million different personal agendas. As former Indiana Congressman Lee Hamilton puts it, it’s much easier to decide which movie to watch when you’re the only person in front of the screen; the decision gets much more complicated when you’re hosting four other people who have different preferences.

Hard, but not at all impossible. Thomas Jefferson cautioned us that education is vital for protecting a democratic society. That means lifting our eyes to see that a community is composed of many divergent perspectives. It is not reasonable to expect a small business owner, who needs to feed her family and keep her employees, to hold the same views about prices and wages as those of someone working at a minimum wage job.

But we can disagree without hating one another. We can have religious faith, or any kind of deep devotion to a set of principles, without thinking we have the right to impose them on others. We’ve seen the results of hate again and again in our recent history; it dehumanizes people and permits us to disregard their views and even, in extreme cases, their right to exist. By considering that ours may not be the only valid ways of thinking, and by being willing to accept half a loaf without demanding every last crumb, we can go a long way toward protecting the institutions — elections, news media, disagreement without violence — that we are so lucky to have inherited. These institutions deserve no less than the effort of each one of us.

League of Women Voters to host legislative update with Indiana legislators

[Press release from the League of Women Voters]:

The public is invited to discuss developments in the current session of the Indiana General Assembly with legislators on Saturday, January 25, 2025, from 9:30 to 11:00 a.m., via Zoom.

All Indiana state lawmakers who represent any portion of Brown, Johnson, and Monroe counties have been invited to update constituents on recent developments in the General Assembly and to respond to questions from constituents. Senators Rod Bray, Cyndi Carrasco, Aaron Freeman, Eric Koch, Greg Walker, and Shelli Yoder and representatives Michelle Davis, Robb Greene, Craig Haggard, Dave Hall, Bob Heaton, Peggy Mayfield, and Matt Pierce have been invited.

Go to bit.ly/3V5WbeY to register and obtain your Zoom link. Questions about the event should be sent to [email protected]. Co-sponsors are the Leagues of Women Voters of Brown County, Johnson County, and Bloomington-Monroe County, and the Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce.

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And in April 2024, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

Limestone Post article by Brookelyn Lambright, Karl Templeton, and Brenna Polovina from the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism, published August 1, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

WFHB reports:

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 1), August 7, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 2), August 14, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 3), August 21, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 4), August 28, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, photography by Benedict Jones, published September 24, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

WFHB reports:

- Apprenticeships (Part 1), October 9, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 2), October 16, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 3), October 30, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

Limestone Post article by Haley Miller, published November 26, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

WFHB reports: