Editor’s note: This article is part of the journalism collaboration “Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate.” Read more about this award-winning series at the end of this article.

As the senior mental health professional at the Bloomington Police Department, Melissa Stone feels she has more freedom to get people the resources they need than at any job she’s held before.

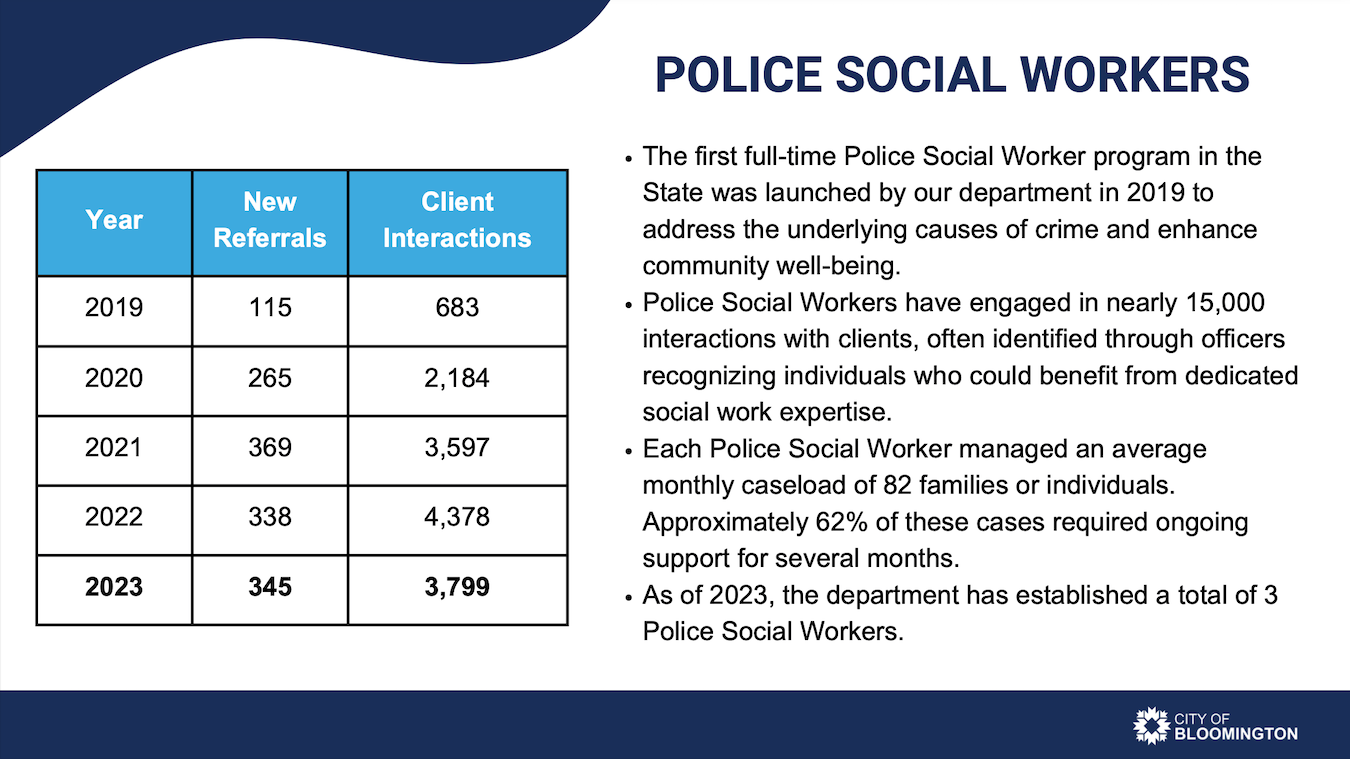

Stone is a member of the department’s Police Social Support Services team, previously called the Police Social Worker program, that was created in 2019 to address the high volume of 911 calls that often require mental-health or social-work services rather than an emergency response.

Melissa Stone is the senior mental health professional at the Bloomington Police Department. | Limestone Post

In 2023, the team served nearly 1,000 individuals and families, responding to domestic violence, suicide, homelessness, and drug abuse calls to provide crisis support and connect clients to social services. Team members work with local organizations such as Centerstone in a mutual referral system, sometimes delivering services more efficiently or creatively than independent mental healthcare professionals or social workers might.

Stone remembers one client who was going to be evicted from her apartment. When Stone visited, she noticed the client had a little dog with a cast on one of its legs, a cast that needed to be changed weekly. Stone worked with a downtown resource officer to not only find the client a new place to live but also transport the dog to the vet every Monday.

“So whenever we’re sitting there taking care of her, taking care of her dog, making sure that she’s getting this stuff that she needed — I think that was one of those moments where it’s like, yeah, this is different than any other job I’ve ever done,” Stone said.

The community’s response to the program has been largely positive, but some still wrestle with the idea of a collaboration between police officers and in-house social workers and whether the two professions with alternate views of justice — criminal versus social — should cooperate. Criticism comes mostly from those who would prefer to see the city divest from the police.

BPD Chief Michael Diekhoff doesn’t agree it’s that complicated. Both fields, he said, exist to help people.

“I don’t understand when people get upset with the fact that we have them [mental health workers],” Diekhoff said, “when in the end all of our missions should be to help people and make sure that they’re taken care of.”

Social services team reduces 911 calls, provides mental health support

In BPD’s social support services model, police officers respond to emergency calls and assess the scene. If they determine the scene is safe, a department mental health professional will arrive to connect the client to resources and provide short-term intervention therapy if needed.

Stone’s team typically sees 70 to 80 clients a month, she said. In addition to working with clients from emergency dispatches, they also get referrals from community partners.

“Whenever we show up and talk to people, we’re figuring out, what services have you had before?” Stone said. “What is the gap that you need [addressed]?”

The social support presence in the police department has helped reduce the number of repeat 911 callers, Stone and Diekhoff said. In one case, a resident in need of home healthcare had called 50 times, including ambulance and fire calls, in two months. After Stone’s team connected the resident to home healthcare services, calls from the same person dropped to zero.

“We want to get it to where people don’t need to call 911 in the first place,” Stone said.

Stephanie Whitehead is a criminal justice professor at Indiana University East. | Courtesy photo

In addition to easing the strain on police department resources, social workers benefit vulnerable people in crisis situations, said Stephanie Whitehead, a criminal justice professor at Indiana University East. They are trained to de-escalate, she said, and they can ensure the police don’t “go in assuming the worst.”

“Letting people know exactly what’s available, what’s an option in that moment, can really calm the situation and make it effective,” Whitehead said.

Diekhoff said the program helps BPD earn trust with the community. People know they have a mental health contact within the department ready to support, he said.

“If we can show up on a scene and we can let people know that we have mental health professionals that work for us, the hope is that that will de-escalate situations,” Diekhoff said.

The BPD social support workers also partner with local organizations such as Adult Protective Services and Centerstone. In the partnership with Centerstone — a nonprofit health system that operates the Stride Resource Center for people in transition from hospitals and jails in addition to other support services — they often refer clients to one another.

Centerstone crisis team lead Jennifer Scott said she is highly supportive of the program and has witnessed how it helps provide continuity of care for those who are struggling.

“Whatever that crisis entails, if it’s mental health or substance or something else, like a tragic death or loss, we can partner together and wrap support around the people involved,” Scott said. “It’s just been amazing.”

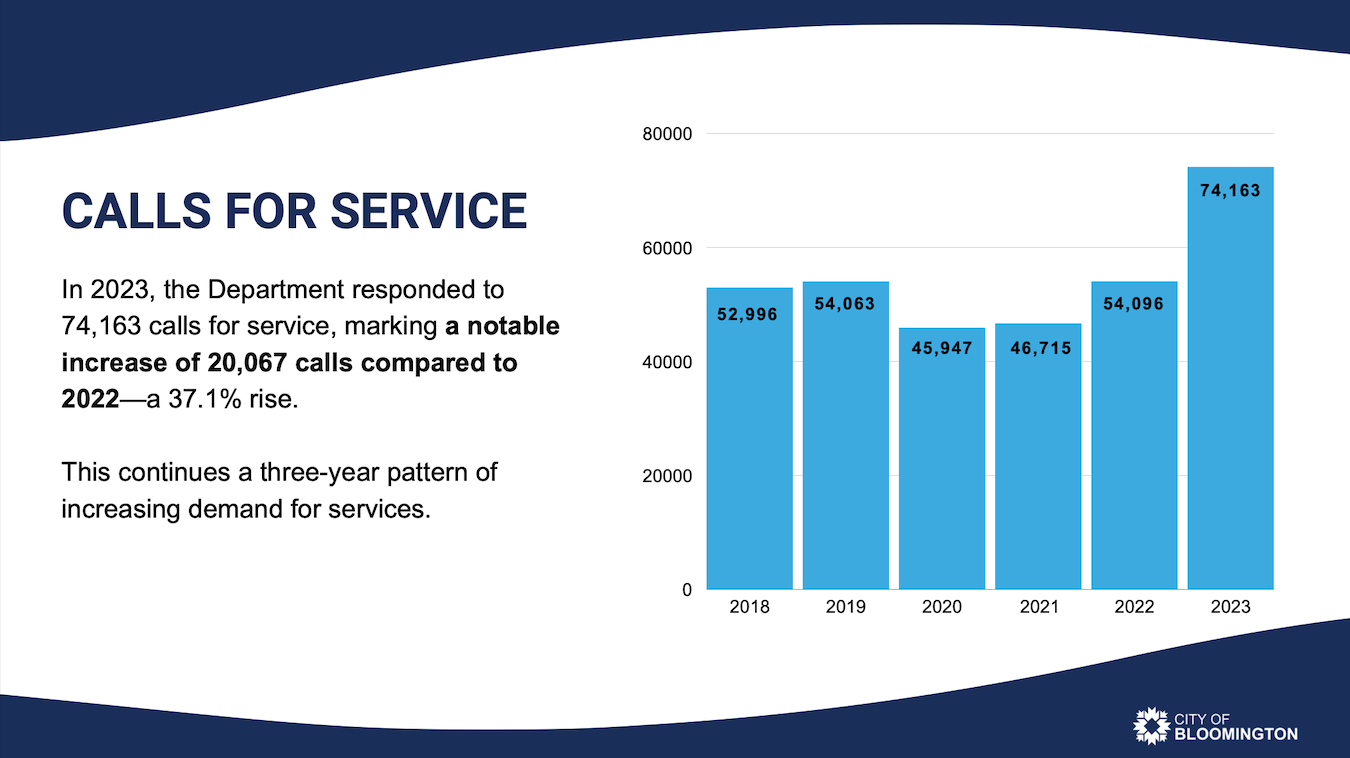

BPD State of Public Safety 2024 Annual Report

Some distrustful of police collaboration

[Editor’s note: “Anna” requested her name be changed for her safety.]

Anna’s boyfriend, now husband, was drunk one night. He beat her up.

First, uniformed police officers showed up, then the social support services team. Anna felt judged by them, she said. In her recollection, they wanted her to help send her boyfriend to prison, something she didn’t want and couldn’t afford. She relied on her boyfriend for transportation as well as care for her chronic medical issues.

She said she didn’t feel she could trust the mental health workers because they were affiliated with the police department. It was hard not to feel intimidated, she said. She felt she was the one treated like she had done something wrong.

Because of client confidentiality, the department would not confirm or deny if Anna was a client, but in general, Stone said in an email to Limestone Post, “there would never be a time” that the mental health team makes decisions on arrests in a domestic violence situation. She added that in those cases, the team works to ensure other needs of the victim are met.

Anna has been critical of the program since that experience and said she would rather the social support services team operate independently of the police, a setup she believes would allow them to be more objective.

“I think they should be a neutral third party, as opposed to someone who is advocating for one side or the other,” Anna said.

BPD’s mental health professionals work closely with local organizations such as Centerstone’s Stride Resource Center on North Morton Street. | Limestone Post

On the question of independence, Stone said that while police officers and the department’s mental health professionals work together, they have separate jobs and stay in their lanes.

“As licensed professionals, we are state-mandated to follow our professional code of ethics, and our officers know and understand how that plays a role in all interactions,” Stone said in an email.

The belief that mental health professionals should not be tied to police departments is frequently encountered in the social work field and shared by some Bloomington residents. In 2020, over 150 people signed a petition against the 2021 city budget that allocated funding for two additional BPD social workers, as reported by BSquare Bulletin.

“Many vulnerable community members lack trust in the police,” the letter reads. “There is greater trust and openness to help provided by social workers, social services, and community care that is provided outside of and independent from the police.”

The petitioners argued the same funding could be used to address Bloomington’s affordable housing shortage, food insecurity, and other social challenges.

Academic critics of police–social work programs often say social workers should be fundamentally anti-carceral and not collaborate with law enforcement. Stone has encountered that criticism from her peers in the field.

She said after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, some social workers implied it was unethical for her to work in a police department. But the social support services team does everything it can to ensure ethical practice, she said, including keeping files separate and confidential from police officers.

In addition, she feels the criticism is unfair because social workers, counselors, therapists, and mental health professionals often navigate systems with inequities, such as hospitals and schools. The fact that injustice exists doesn’t mean social workers should avoid those places, Stone said.

“If you put social workers within systems that appear to be broken, you can improve internally as well as externally what’s going on with that,” she said.

‘It’s going to continue to grow’

Police social work programs exist throughout Indiana, including in Valparaiso, Terre Haute, and Carmel. Diekhoff said BPD has served as a model for other cities.

Bloomington Chief of Police Michael Diekhoff | Limestone Post

“We kind of are a go-to agency,” Diekhoff said. “People who are implementing these programs reach out to us to get advice, feedback, things like that, on how they can set up their own program.”

His best advice is to make sure the first hire is a good fit. At BPD, mental health professionals work closely with officers, both in the field and at the station. They offer mental health training and promote officer wellness.

“We respond to a lot of crazy stuff, and it takes a toll on a person,” Diekhoff said. “If we can have in-house people — that the officers know, trust, deal with on a daily basis — help them if they’re struggling with issues, then that’s a win.”

Stone said she has watched programs similar to the Police Social Support Services team become increasingly popular since she started with BPD in 2019. She’s consulted with departments around the country and in Canada and the Bahamas. To her, it’s clear there’s a desire for mental health professionals in law enforcement.

“Law enforcement agencies are seeing a need to have some sort of mental health person as a resource easily accessible to them,” Stone said. “I think it’s going to continue to grow where it’s going to be ideally standard, and probably quite standard eventually, to have that in place.”

BPD State of Public Safety 2024 Annual Report

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

Limestone Post article by Brookelyn Lambright, Karl Templeton, and Brenna Polovina from the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism, published August 1, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

WFHB reports:

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 1), August 7, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 2), August 14, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 3), August 21, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 4), August 28, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, photography by Benedict Jones, published September 24, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

WFHB reports:

- Apprenticeships (Part 1), October 9, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 2), October 16, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 3), October 30, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

Limestone Post article by Haley Miller, published November 26, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

WFHB reports:

- Police and Social Work, January 29, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 2), February 5, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 3), February 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

Limestone Post article by Marjorie Hershey, photos by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian, published January 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

WFHB reports: