Editor’s note: This article is part of the journalism collaboration “Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate.” Read more about this award-winning series at the end of this article.

On a cool March morning in northwestern Monroe County, a half-dozen Sycamore Land Trust volunteers worked steadily in the mudflat around a still, shallow pool of water, firming in plugs of sedges, bulrushes, and other native wetland plants. At the far side of the pond, a greater yellowlegs, a shorebird on its way from South America to Canada for summer breeding, picked its way along the water’s edge. That was just the start. By late April, land trust employees had identified river otters, beavers, frog eggs, crawdad burrows, a half-dozen migratory shorebirds and waterfowl, numerous nesting birds, and an endangered snake — all in a habitat established only six months earlier.

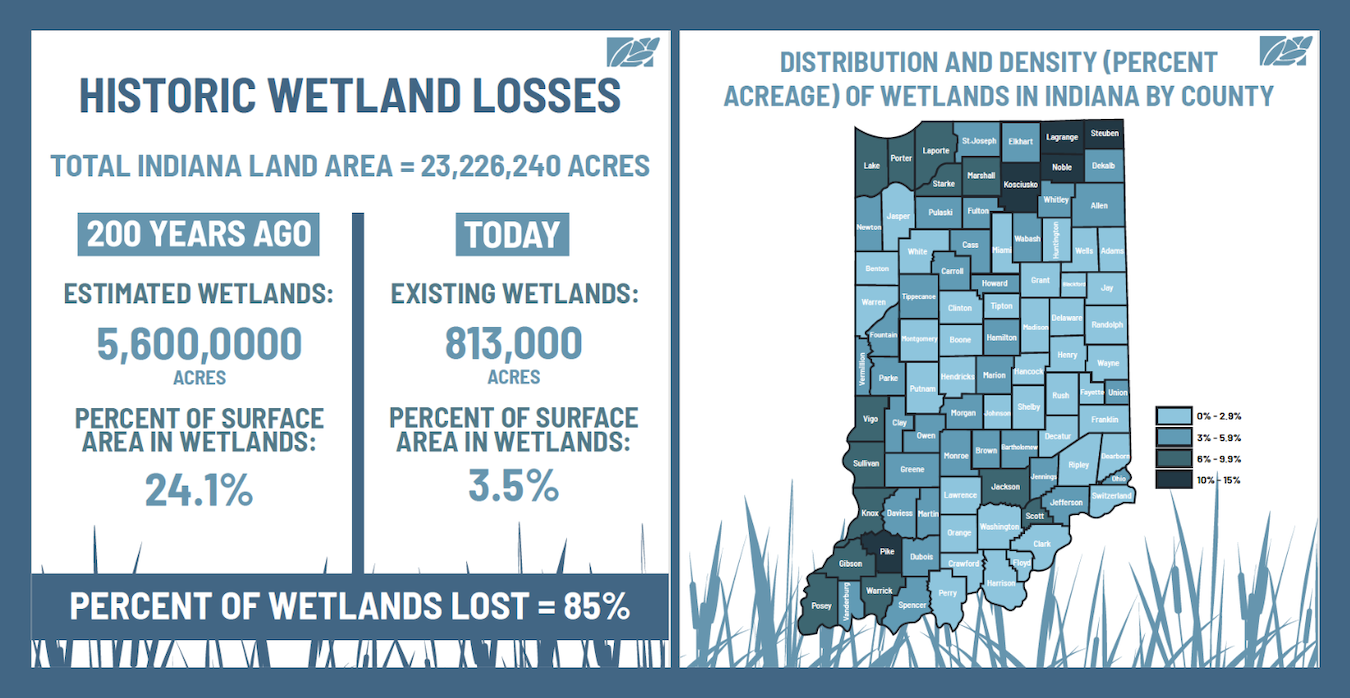

The work at Sam Shine Foundation Preserve to restore almost 650 acres of former farm fields to their original wetland state is a drop in the bucket considering the enormous loss of Indiana’s wetlands to agriculture and development in the last 200 years. In the late 18th century, 24 percent of the state — more than 5.5 million acres — was covered in wetlands. Today, only 813,000 acres of wetland, or 3.5 percent of the state, remain. In other words, Indiana has lost 85 percent of its wetland habitats — the fourth highest proportion in the country. And it stands to lose more.

Indiana legislators have passed measures in the past three years that significantly roll back wetland protections. Above, the Indiana Statehouse in Indianapolis. | Limestone Post

In the last four years, federal and state legislators have passed measures that significantly roll back wetland protections. In Indiana, which until recently had relatively strong wetland preservation laws, the issue has played out broadly as a conflict between two camps.

On one side are environmentalists and others who argue wetlands must be preserved because of the critical functions they provide, including flood prevention, water purification, and carbon sequestration, as well as a specialized habitat for specific plants and animals.

On the other side are property owners and developers who say the state’s wetland regulations are confusing, complicated, and costly to navigate, driving up construction prices and hampering growth. Being able to build on wetlands, they say, will help address the state’s housing shortage and make homes more affordable.

In between are myriad questions, about issues ranging from the impact of the shifting climate on flood zones to the widely acknowledged complexities of the state’s wetland classification system.

“The bottom line is that wetlands in Indiana have lost most of their protection in just the recent few years, and without some changes at the state level, we will see accelerated wetland loss,” said Dr. Indra Frank, who retired April 30 as water policy director for the Hoosier Environmental Council. “Now the question becomes, ‘What does it mean to have accelerated wetland loss? What are the implications?’ And that takes us back to ‘What do wetlands do, and if we’ve lost them, what functions are we losing?’”

Source: Indiana Department of Natural Resources | Graphic by Melanie Roberts for the Indiana Environmental Reporter

Federal and state laws lead to wetland loss

In 2007, on the edge of Priest Lake in the northern tip of Idaho, Michael and Chantell Sackett began filling a construction site with gravel to prepare it for the house they planned to build. The lot was found to contain a federally protected wetland, and the Sacketts soon found themselves embroiled in a legal tussle with the Environmental Protection Agency. The case wound its way to the top of the judicial system, ending in 2023 in a 5–4 U.S. Supreme Court decision in favor of the Sacketts.

Dr. Indra Frank, water policy director for the Hoosier Environmental Council | Courtesy photo

The decision upended a pivotal definition under the Clean Water Act of what are known as protected “waters of the United States,” commonly referred to as WOTUS. When the act was passed in 1972, it was understood that WOTUS included not just bodies of water connected by rivers and streams but also wetlands, ponds, and other water sources that might not be linked directly on the surface but that still composed part of an overarching aquatic ecosystem.

The Sackett decision determined that “isolated wetlands” — those that didn’t connect on the surface to another body of federally protected water — no longer qualified for protection under the Clean Water Act.

Even before Sackett, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife report to Congress covering the years 2009–2019 noted accelerating losses of wetlands nationwide.

“This report indicates that wetland loss rates have increased by 50 percent over the last decade and continue to disproportionally impact vegetated wetlands such as marshes and swamps,” Deb Haaland, secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior, wrote in the introduction to the report, which was released this year. “Approximately 670,000 acres of vegetated wetlands, an area greater than the land extent of Rhode Island, disappeared between 2009 and 2019.”

But the Sackett decision opened the door for further relaxation of the rules, and for legislatures around the country to decide how they would oversee previously protected terrain. In response, several states decided to strengthen their wetland protection laws. Indiana went in the other direction.

“Here in Indiana, we went from about 80 percent of our wetlands having protection under the Clean Water Act to 20 percent,” Frank said.

In fact, until recently, Indiana’s laws governing isolated wetlands were more protective than those of many other states. A 2003 law established a classification system for wetlands based on their quality, ranging from Class I for the lowest quality to Class III for the highest. The law required permits for building on all classes of wetlands and required property owners or developers to pay for mitigation, or installation of new wetlands, to replace those lost to construction.

In 2021, Senate Enrolled Act 389 determined a permit was no longer required to develop on Class I wetlands, and it exempted most Class II wetlands from mitigation requirements. Then in 2024, despite recommendations to the contrary from the Indiana Wetlands Taskforce created to review regulations after the passage of SEA 389, lawmakers passed HEA 1383, further loosening wetland restrictions.

The bill exempts some Class II wetlands from permitting requirements, while downgrading some Class III areas to Class II. The law took effect the moment it was signed by Gov. Eric Holcomb on February 12.

Barry Sneed, public information officer for the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM), sent this statement to Limestone Post about the bill:

“HEA 1383 recognizes changes in federal law that removed a significant amount of wetlands from federal regulation. Specifically, the law revises definitions for Class III wetlands preserving protections for Indiana’s most rare and ecologically important wetlands. Class III wetlands such as circumneutral bog, cypress swamp, dune and swale, panne, sinkhole pond, sinkhole swamp, and sand flat are especially unique and extremely difficult to replace.

“HEA 1383 maintains requirements for wetland creation and replacement when certain types of wetlands are impacted, but also provides additional incentives for developers to offset wetland impacts by preserving and/or restoring existing wetlands.”

Sneed referred further questions to members of the Indiana General Assembly.

Indiana state Sen. Shelli Yoder, D-Bloomington, who has been outspoken in opposition to the recent wetland bills, said Indiana had done a “phenomenal job” protecting wetlands through its classification system, but had done away with many of those protections in just four years.

“

Working around certain small pockets of wetland sometimes can make a project unfeasible because of mitigation costs and/or you simply can’t develop on that property.

”

—Rick Wajda

Not only are wetlands now more vulnerable to loss, Yoder said, it also will be harder to determine how many will be lost in the future. Before 2021, according to IDEM, Indiana had about 25,000 acres of Class III wetlands. With no state inventory available, it’s impossible to say how many acres will remain now that some of those Class III sites are being downgraded to Class II.

Also, until recently, IDEM could track wetland loss by the number of development permits issued. With Class I already exempt and much of Class II soon to be exempt from the permitting process, “it will be very difficult to know how much of our wetland loss will occur, because we won’t have that tracking mechanism,” Yoder said.

What exactly is a wetland?

The boardwalk at Sycamore Land Trust’s Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve. | Photo by Anne Kibbler

If you stroll along the boardwalk at Sycamore Land Trust’s Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve or visit the Indiana Department of Natural Resources’ Stillwater Marsh–Northfork Waterfowl Resting Area, both in Monroe County, it’s pretty clear that what you’re looking at is a wetland.

At Beanblossom Bottoms, the boardwalk is elevated above boggy terrain and stretches of standing water, filled with wetland plants, amphibians, reptiles, and birds attracted to the unique habitat. Stillwater–Northfork, a combination of marshland and open water, is a haven for migrating birds, as well as year-round species such as the great blue heron.

But not all wetlands are so easily identified. A wetland can be a patch in a farm field or a city lot next to a stream. Various tools such as aerial surveys paint broad brush strokes, picking out areas that might have poor drainage, but they can’t as easily identify individual sites. The only way to know for sure is for a wetland scientist to survey the land up close.

Rachele Baker, president and founder of Little River Consultants and treasurer and founding member of the Indiana Wetlands Association, has 30 years of experience working in natural resources. As a certified professional wetland scientist, she is called in for consultation when property owners or developers want to build on land that might be a wetland. In Bloomington, for example, she consulted with Indiana University on the renovation of its golf course, which lies in the watershed for Griffy Lake.

Baker starts her assessments by looking at aerial photography. Indiana has a wetland map that is part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Wetlands Inventory, based on an aerial survey conducted between 1980 and 1987. It maps just over 3,300 acres of wetland in Monroe County. But Baker said the inventory is of limited use because of its age and the quality of the photography.

Rachele Baker, president and founder of Little River Consultants and treasurer and founding member of the Indiana Wetlands Association | Courtesy photo

She uses more recent aerial photography of the state, taken in 2005, as well as Google Earth and the federal Web Soil Survey to narrow down what may or may not be a wetland. After that, she goes to the site to collect data on topography, the plant community, soil type, and amount of water in the soil, looking for clues that confirm whether the area is indeed a wetland.

For sites that she determines fall under federal jurisdiction, she sends her opinion to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which helps regulate WOTUS, to see if they agree. For sites under state jurisdiction, she fills out a worksheet to determine the classification and sends that recommendation to IDEM.

“That’s where some of the stickiness has started to happen,” Baker said.

Because of overlapping definitions in the 2021 law, it’s been possible for the consultant and the state agency to disagree on the classification, yet for both to be right.

“If you went to the worksheet, you could make it come out either way,” Baker said.

“They revised those definitions this past session and didn’t make it any better,” she said. “It’s still as difficult to tell as ever. There are no clear lines between the classes. You can get an endless loop of not agreeing on what class it is, and there’s no way to prove who’s right, because you both are, according to the definitions.”

Yoder introduced an amendment to HEA 1383 this spring, trying to clarify the language and use federal definitions rather than the state’s classification system.

A great blue heron at Stillwater Marsh–Northfork Waterfowl Resting Area at Monroe Lake | Photo by Anne Kibbler

“Existing state wetland classifications involve cumbersome rules and subjective standards that are confusing for regulators, advocates, landowners, and developers,” she said. “My proposed amendment would have streamlined these classification standards, ensuring faster, easier, and more consistent wetland permitting in Indiana while improving wetland protections.”

The amendment didn’t get a hearing.

Baker hopes Yoder’s proposal will be reintroduced next year. In the meantime, she worries that the new rules are chipping away at protections, and that losing even the smallest wetlands will have a significant impact.

“That’s where we’re going to have the big loss,” Baker said. “It’s the little pockets in all the farm fields that now are going to be paved over and filled in, and it’ll be a housing addition. That’s a lot of depressional storage for flooding and groundwater recharge that we’re losing, one little pocket at a time, but it all adds up.”

The value of wetlands

In a state covering 23 million acres, the loss of 261 acres might seem insignificant. That’s the amount of wetlands the Hoosier Environmental Council estimates were lost from 2021 to 2023, the first two years after Class I exemptions went into effect.

But the work of wetlands is hard to replicate, Frank and others say. Wetlands have been referred to variously as sponges or kidneys, soaking up and neutralizing pollutants, purifying excess water during times of rainfall, slowing the release of water, preventing erosion in the aftermath of flooding, and storing water that supplies wells and streams, especially important in times of drought.

Protecting wetlands means protecting unique habitat for countless plants, amphibians, birds, and reptiles, such as this turtle at Beanblossom Bottoms. | Photo by Anne Kibbler

“Also, with wetland preservation and the storage of stormwater that wetlands provide, it can mean a reduction in the amount of built stormwater infrastructure, and that can be a savings for our local communities,” Frank said. In Bloomington, the city has spent about $26 million in the last 24 years to improve its stormwater management system in the wake of significant downtown flooding.

An acre of wetland is estimated to hold 1 million to 1.5 million gallons of water, Frank said. So when the state lost 261 acres, that amounted to the loss of 261 million to 390 million gallons of water storage.

To put a dollar value on that loss, Frank suggested looking at what it might cost to build infrastructure to store 261 million gallons of water. She pointed to the DigIndy Tunnel System, a two-decades-long, 28-mile tunnel project in Indianapolis scheduled for completion in 2025. The 20-foot-diameter tunnels are built 250 feet down in limestone and dolomite rock, with the purpose of storing about 250 million gallons of sewage and wastewater overflow after rainfall — which otherwise would go straight into the White River — and diverting it to a treatment plant in Southport. The project cost $2 billion.

Comparing that 250 million gallon tunnel system with the estimated 261 million gallons of water storage lost to wetland development, “I’m arguing that in the first two years after SEA 389, the state lost $2 billion worth of stormwater storage,” Frank said.

Indiana state Sen. Shelli Yoder | Limestone Post

In another calculation, an Indiana Department of Natural Resources wetland fact sheet from 2021 estimates the state’s 800,000 acres of wetland provide $1.8 billion in water storage, $850 million in erosion prevention, and 81 million acres of cropland runoff purification each year. In 2016, Indiana’s wetlands also helped attract anglers who spent more than $1.6 billion on fishing-related expenditures, as well as photographers and wildlife observers who spent $2.5 billion, and hunters who contributed $533,000 to conservation through license and waterfowl stamp purchases.

Chris Craft, Janet Duey Professor of Rural Land Policy at Indiana University’s O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, says when it comes to the value of wetlands, a lot of landowners want to know its monetary worth.

“Biodiversity is important, but it’s hard to put a dollar value on that,” said Craft, who has been studying wetlands for more than thirty years. “People want to see dollars and cents — ‘What am I getting by having this wetland on my landscape?’”

In a 2017 study of wetlands in the St. John’s River watershed in Florida, Craft and his colleagues estimated the economic value of the wetlands’ nitrogen and phosphorus filtering functions by comparing the cost of removing the same amount of those pollutants in a wastewater treatment plant.

“It was in the hundreds of millions to billions of dollars” each for the phosphorus and nitrogen, Craft said.

Craft said that 20 years ago, he would have cited water quality as the biggest economic benefit of wetlands. Now, with increased flooding caused by climate change, it’s hydrologic storage.

The Indiana Climate Change Impacts Assessment, published by Purdue University in 2018, found average annual rainfall in Indiana has increased by 5.6 inches since 1895, with more frequent heavy rainfalls that could lead to flooding. Heavy rain events are expected to continue to increase in severity and frequency.

“Flood control has become a lot bigger issue,” Craft said. “You see the insurance companies bailing out places where there’s climate risk, be it wild fires or hurricanes or just river flooding. I’m not an economist, but I think a dollar value can be put on that, and I’m pretty sure these insurance company actuaries are doing that.”

In Indiana, liability for property in areas with increasing natural disasters is a topic familiar to Yoder.

“I was having a conversation with insurers who were saying they cannot afford to insure homes in some of the places where they’re seeing consistent and increasing natural disasters,” she said. “That is something we as Hoosiers and legislators need to be mindful of and working on. We need an adaptation plan and a mitigation plan. Developing [on] our wetlands is the wrong direction.”

Wetland biodiversity

When Sycamore Land Trust acquired the Sam Shine Foundation Preserve, the farm fields had been largely stripped of trees. As on thousands of acres all over Indiana, clay drainage tiles — which are actually pipes — had been installed to siphon away excess water. The land was then planted in row crops, mostly corn and soybeans.

John Lawrence, director of Sycamore Land Trust | Courtesy photo

Once the drainage tiles were removed and the shallow ponds were excavated, wildlife soon appeared. On a visit in late April, land trust director John Lawrence identified ringneck ducks, blue-winged teal, mallards, northern shovelers, and two types of sandpiper. He also heard the call of a sora, a marsh bird he described as looking like “a tiny black chicken,” and saw an endangered Kirtland’s snake.

Nationally, almost 35 percent of rare and endangered animal species depend on wetlands for survival, and in Indiana, more than 60 animal species and more than 120 plant species that are endangered, threatened, or rare make their home in wetlands, according to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources.

Clay drainage tiles removed from the Sam Shine Foundation Preserve. | Photo by Anne Kibbler

Although entities like federal and state governments have set aside land such as the Hoosier National Forest or Brown County State Park for preservation, land trusts take care of valuable habitats that otherwise would have seen no protection, Lawrence said.

Sycamore belongs to the Indiana Land Protection Alliance, whose member groups oversee more than 176,000 acres of land around the state. Sycamore itself protects about 11,000 acres in south-central Indiana.

Chris Fox, the trust’s land stewardship director, said it’s easy to be discouraged. But every patch of ground counts, he said, noting that property owners next to Sam Shine, influenced by the new preserve, are now creating a wetland on their own land.

“It’s really exciting to see that if you build something and you do it in the right place and in the right way, things respond really quickly,” Fox said. “It verifies why wetlands are so important, because they are biological hotspots, and probably also the habitat is in such short supply that things just can’t wait to get in there.”

Fox said a lot of people look at wetlands and see only problems — soggy areas that need to be drained, full of mud and mosquitoes. Even species that are not “charismatic” play a role, feeding birds and other animals.

“You can’t put a value on the services provided by the animals that maintain the ecosystem,” Fox said.

Chris Fox, land stewardship director of Sycamore Land Trust, seen here drilling holes for planting. | Courtesy photo

He uses the analogy of a tapestry to describe the interconnection among plant and animal species in wetlands. “If you snip one thing, and it may seem like this really small thread, it starts to unravel. The more we study things, the more we realize we just don’t know very much about how ecosystems work.”

On Sycamore Land Trust properties, staff have identified the endangered Kirtland’s snake and the cyprus firefly. The latter was discovered for the first time in Mississippi less than ten years ago. It’s been seen in only two places in Indiana, including Beanblossom Bottoms.

A single species of firefly may seem insignificant, Fox said, but other species could depend on it for pollination or food, with others in turn depending on them.

He’s also seen firsthand the critical role beavers have played in the transformation of Sycamore Land Trust’s preserves. Beaver dams can reduce flooding downstream and increase biodiversity in wetlands.

Lawrence agrees that every acre of land that can be preserved can make a difference.

“Even relatively small patches of habitat are very important,” he said. “There are so few wetlands in Indiana compared to what was here historically. Whatever one feels about changes in legislation, the simple fact is that with less government protection, there will be more wetlands converted to other uses, so it’s all the more important to protect and preserve what we can.”

A solution to the housing crisis?

Imagine you’re planning to build a group of houses on a piece of undeveloped land. You call in a wetland scientist to survey the site, and you discover that dotted around the property are a few small patches — maybe a tenth of an acre each — that qualify as wetlands. Before the passage of HEA 1383, those isolated wetlands might have required expensive testing and mitigation, or possibly the scrapping of the whole project, said Rick Wajda, CEO of the Indiana Builders Association (IBA).

“Sometimes you can work around them, but sometimes you can’t,” said Wajda. “There are only so many ways to lay out a subdivision and make sure you have enough lots there to be able to build out the project at a price Hoosiers can afford. Working around certain small pockets of wetland sometimes can make a project unfeasible because of mitigation costs and/or you simply can’t develop on that property.”

Rick Wajda, CEO of the Indiana Builders Association | Courtesy photo

Development is at the crux of the recent tightening of state and federal laws. The Indiana Builders Association cited support for revised wetland classifications as one of its two top priorities for the 2024 session.

Wajda said the association believes the new system streamlines the classification process and makes it easier for property owners to understand where they can and can’t build. He hopes the new legislation can help solve Indiana’s housing shortage by opening up land that previously would not have been developed because it contained some low-quality wetlands.

The association, which worked with wetland scientists during its evaluation of the legislation, supports the preservation of the state’s highest quality wetlands, Wajda said.

“In Indiana, we’re taking a hybrid approach to that to say, ‘Yes, there are some high quality, rare wetlands that should be protected if at all possible,’ but also realizing we have a need for housing, we have a need for economic development in our state.”

Yoder discussed HB1383 with the IBA and acknowledged the appeal of its position during an affordable housing crisis, but she disagreed with its logic.

“To really address the housing crisis, developing our wetlands is a counterproductive place to start because its going to take so much attention, so much money, and it’s so expensive on the back end,” she said.

Removing wetlands that naturally soaked up floods and retained water for use during droughts also could lead to expensive problems in the future, she said. And developers’ argument that building more expensive housing will trigger a trickle-down effect leading to more affordable housing down the line is a misconception.

“I think that’s how HB1383 gets passed, but I don’t expect it to result in bringing down housing prices whatsoever,” she said.

Craft, of IU’s O’Neill School, agrees.

“From a development point of view, I don’t see the existence of isolated wetlands in Indiana as a big detriment to homebuilders, even though they said there is,” he said.

Chris Craft, professor at Indiana University’s O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs | Courtesy photo

Craft reiterated what he said in March on the O’Neill School’s podcast, “O’Neill Speaks,” when he referenced the business community’s allusion to “soaring” home prices.

“I said, ‘Whoever said that was disingenuous at best and dishonest at worst,’” he said. “Wetlands aren’t responsible for high house prices. Let’s blame it on supply chain issues, the higher cost of everything. It’s not because wetlands are being overprotected.”

There are other reasons for not developing housing on wetlands, according to a 2022 letter from the HEC’s Frank to the Indiana Wetlands Task Force.

“Since 96.5 percent or more of Indiana’s land is not wetland, there appears to be ample space for construction on ground that is not wetland,” Frank wrote. “Also, construction in wetlands is discouraged since it leads to cracked foundations and problems with seepage and mold.

“While environmental deregulation may provide short-term savings to a particular developer on a particular site, it could also create more widespread negative impacts. Loss of wetlands increases the risk of flooding downstream, which hurts the overall economy of the state, as well as hurting the housing supply through flood damage.”

Mitigation also is problematic, Frank wrote. She cited past studies that found some wetlands created to mitigate loss to construction were built improperly or not at all. And often mitigation sites are so far from the destroyed wetland that they will not benefit the original site.

Yoder is frustrated by the idea that if you build housing on a wetland, you can simply replace it with another wetland somewhere more convenient. The replacement wetlands are likely to be inferior, she said, and they cost money.

“That is not a conservation mindset,” she said.

“

Because of overlapping definitions in the 2021 law, it’s been possible for the consultant and the state agency to disagree on the classification [of a wetland], yet for both to be right.

”

—Rachele Baker

Yoder is concerned, too, about separate legislation passed in the spring, also intended to combat the housing shortage but also, she believes, with the potential to harm the environment.

The bill, HEA 1108, sets a statewide maximum slope percentage at 25 percent on which structures can be built, unless the site in question is within the watershed area of a reservoir that provides drinking water. Until now, Monroe County has limited construction to slopes of no more than 12 percent to 15 percent, depending on designated areas, largely because of its hilly terrain and limestone topography. The local ordinance is intended to prevent erosion and also to prevent problems with septic systems on steep slopes.

Indiana state Rep. Dave Hall | Courtesy photo

The bill was authored by Rep. Dave Hall, R-Norman, who represents Brown County and parts of Monroe and Jackson counties. Hall, a farmer and the owner of Dave Hall Crop Insurance, noted that he voted against both SEA 389 and HEA 1383, siding with those who wanted to keep stricter wetland protections.

“Monroe County faces a housing shortage made worse by overly restrictive local building ordinances, like slope restrictions, which no other county has in place,” Hall said in a statement to Limestone Post. “This shortage is driving up home prices and forcing residents to leave the county for more affordable options. House Enrolled Act 1108 aims to strike a balance between land use rights and responsible development while restoring control exactly where it should be — with landowners. Any added cost is not the county’s concern, only between landowners and home builders.”

The bill was backed by the Bloomington Economic Development Corp. and the Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce.

In an interview with Indiana Public Media, Monroe County Planning Department Director Jackie Jelen said the new regulation likely will increase workloads and costs for the department, and lead to increased costs for taxpayers.

Yoder, too, finds the new slope law problematic. Many homeowners in Monroe County and around the state rely on septic systems instead of municipal sewer hookups because of cost, location or other circumstances, she said. She is concerned that increasing development on steeper slopes might lead to the need for more septic systems, which can fail and can be expensive to maintain.

“Unfortunately, failing septic systems are a contributor to poor water quality in our creeks and streams,” she said. “Indiana does not track septic systems in the state, nor does the state track the integrity of such systems. So, increasing the reliance on septic systems increases the use of wastewater systems that are difficult to manage when it comes to public health.”

“

Construction in wetlands is discouraged since it leads to cracked foundations and problems with seepage and mold.

”

—Indra Frank

Hall said any septic issues stemming from the new law would be addressed by the county health department.

“Issues with erosion or runoff would more than likely be a civil issue,” he said. “Indiana’s other 91 counties have operated without any restrictions on the basis of slope, and this law does not apply to watershed areas or drinking water sources.”

But Yoder said there should be concern about the impact of every watershed, not just those connected to a reservoir, which she described as “a carveout” in HB 1108 meant to protect water quality in Lake Monroe.

“Every Hoosier deserves access to a quality environment, safe drinking water, and affordable housing,” she said. “Thoughtful and sustainable development can promote all these goals.”

The future of wetlands

In the wake of Sackett and recent Indiana wetland laws, there is some room for optimism.

The Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers pledged to work within the limits of federal law to help state, tribal, and local partners safeguard their waters.

And on Earth Day in April, the White House announced The America the Beautiful Freshwater Challenge, an effort to conserve U.S. waters and wetlands in the wake of Sackett.

Indra Frank acknowledges the presidential election in November could have a significant impact on the future of wetlands, noting that if Donald Trump is elected, any effort in Congress to establish better protection for wetlands most likely would fail.

But at the state level, despite what she described as a “very sobering” legislative session this spring, she sees some glimmers of hope.

One is that there was bipartisan opposition to HEA 1383. Two Republican representatives and eight senators voted against the bill.

Wetland resident red admiral butterfly. | Photo by Anne Kibbler

Another positive development, Frank and Yoder said, is the passage of SEA 246, authored by Yoder and Republicans Sue Glick and Blake Doriot. The bill allows property owners to have parcels as small as a half acre classified as a wildland and to apply for a corresponding tax break. The law previously applied only to property of 10 acres or more.

Once designated as a wildland, the property must be protected as is, or it could even be turned into wetlands. The bill passed unanimously in the Senate and received only two no votes in the House.

“SEA 246 is a positive step forward to help encourage the protection and rehabilitation of our wetlands — what we’ve lost and what we want to protect,” Yoder said.

Yoder said she will continue to make wetlands a priority for future sessions. And there are indications public sentiment in Indiana favors her stance.

In her 2022 letter to the Indiana Wetlands Taskforce, Frank cited numerous instances of public support for wetland protection. They included a letter to Gov. Holcomb with more than 110 signatures from a broad range of organizations; a 2020 poll in which 78 percent of respondents said protecting Indiana’s environment should be a priority; and a 2021 poll showing 94 percent of respondents supported wetland protections.

Frank is heartened, too, by public and government responses to a plan to divert 100 million gallons of water a day from Tippecanoe County to Lebanon, Indiana, to support a planned 9,000-acre manufacturing and research-and-development site.

As a result of opposition to the project, known as the LEAP Research and Innovation District, Gov. Eric Holcomb ordered the Indiana Finance Authority to study the water supply in north central Indiana. He recently expanded the purview of the study to include all headwaters of the Wabash River.

Frank hopes the discussion will draw more attention to the importance of the water supply and to the role of wetlands in storing and purifying water.

“Indiana has had the luxury of taking its water largely for granted,” Frank said. “But not all parts of the state have ready access to indefinite amounts of water. Hopefully, the discussions around water supply and areas that need more water than they actually have will help to highlight the importance that wetlands can play.”

Nationally, almost 35 percent of rare and endangered animal species depend on wetlands for survival, and, according to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, in Indiana more than 60 animal species and more than 120 plant species that are endangered, threatened, or rare, make their home in wetlands. Above (l-r): widow skimmer dragonfly, a green frog, and a common watersnake, all found in Monroe County wetlands. | Photos by Anne Kibbler

Editor’s note: The author recently began volunteering in the Sycamore Land Trust native plant nursery and helped with plantings at Sam Shine Foundation Preserve.

Want more about the local environment? Check out these Deep Dives:

- “On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest,” a photo essay by Steven Higgs

- “How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?” by Michael G. Glab, photography by Anna Powell Denton

- “The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape,” by Rebecca Hill, photography by Benedict Jones

- “Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus,” by Laurie D. Borman, photography by Jeremy Hogan

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

Limestone Post article by by Brookelyn Lambright, Karl Templeton, and Brenna Polovina from the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism, published August 1, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

WFHB reports:

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 1), August 7, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 2), August 14, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 3), August 21, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 4), August 28, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, photography by Benedict Jones, published September 24, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

WFHB reports:

- Apprenticeships (Part 1), October 9, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 2), October 16, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 3), October 30, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

Limestone Post article by Haley Miller, published November 26, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

WFHB reports:

- Police and Social Work, January 29, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 2), February 5, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 3), February 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

Limestone Post article by Marjorie Hershey, photos by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian, published January 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

WFHB reports:

- Political Polarization, (Part 1), March 19, 2025

- Political Polarization, (Part 2), March 27, 2025

- Political Polarization, (Part 3), April 2, 2025

Mental Health Issues Are Increasing Dramatically Among Hoosier Youth

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, photography by Benedict Jones, published April 3, 2025

Mental Health Issues Are Increasing Dramatically Among Hoosier Youth

WFHB reports: