[Editor’s note: This is the third article in a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post. You can read more about the collaboration at the end of this article. The first two articles were written by journalist Steve Hinnefeld, who reported in February on housing problems in Monroe County and in March on possible solutions, with photography by Jim Krause.]

[Editor’s note: This is the third article in a series called “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate,” a collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post. You can read more about the collaboration at the end of this article. The first two articles were written by journalist Steve Hinnefeld, who reported in February on housing problems in Monroe County and in March on possible solutions, with photography by Jim Krause.]

Since 1999, the opioid epidemic has devastated counties, towns, and cities across the United States and Indiana, forcing them to reboot prevention, treatment, and harm reduction services that were mostly depleted. These cities, towns, and counties seek to recover those costs from the opioid manufacturers and distributors who fueled the epidemic. The first settlement distribution from opioid distributors has been released, and communities are in line to collect.

Future payouts of the national Opioid Distributor Settlement

The first settlement dollars, $26 billion, come from opioid distributors AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, McKesson, and manufacturer Johnson & Johnson. The settlement dispenses $21 billion to states’ coffers over eighteen years. The Johnson & Johnson payment of $5 billion will be disseminated over nine years.

So far, Monroe County and the city of Bloomington have received two payments each, in 2022 and 2023, for the opioid distributors settlement. (top) Monroe County Health Services Building on West 7th Street; (bottom) Bloomington City Hall and Fernandez Plaza. | Photos by Benedict Jones

Opioid tort lawsuits date back to the 2000s. Initially, families brought cases, and failed class action suits followed those. It wasn’t until the government began bringing cases that distributors, manufacturers, and pharmacies succumbed to the inevitability of their coming losses.

Based on state nuisance, fraud, and unjust enrichment theories, most of those lawsuits became multi-district litigations, meaning that they included multiple districts throughout the United States as litigants. The irony in all this? The glaring omission of personal liability in settlement documents by those who led these practices. This is an aspect that particularly rankles family members of overdose victims.

According to the analysis Public Health Value of Opioid Litigation by Rebecca L. Haffajee, acting assistant secretary for planning and evaluation at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), public health and tort litigation objectives served by this litigation (1) filled the gap in pharmaceutical opioid and addictive substance federal regulations, (2) highlighted the failure of legislatures and all government agency levels to prevent addiction and opioid harms, and (3) demonstrated the failure of these companies to self-regulate to ensure the safe use of their products.

In her analysis, Haffajee asserts that these tort settlements will “infuse much-needed money, behavior changes, and public accountability for prescription opioids and related harms.” How it will evolve, though, remains to be seen.

Still, Douglas Huntsinger, executive director of NextLevel Recovery Indiana, asserts that the best way to approach the distribution of opioid settlements is to keep it local. “Solutions are best and most often best handled at a local level,” he says.

Additional settlements are coming. While the total national settlement dollars are significant, an estimated $54 billion, many hope the opioid settlements will change behavior and reorient the approach to substance use disorder and mental health for the long term.

The pharmacy suppliers settlement with CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart will release about $13.8 billion nationally. Bloomington and Monroe County are settlement participants. | Photo by Benedict Jones

The pharmacy suppliers settlement with CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart will release approximately $13.8 billion. For Indiana, “It looks like that will be about $404 million,” Huntsinger says. “The Walmart settlement, $60 million, is a one-time payment to Indiana, but the rest of the settlement will pay out between seven and fifteen years.” The CVS and Walmart settlement documents list Bloomington and Monroe County as settlement participants.

Settlements involving Purdue Pharma for approximately $5.5 to $6 billion are now enmeshed in unresolved bankruptcy proceedings. Those with Mallinckrodt ($1.7 billion), AbbieVie Allergen ($2.4 billion), Teva ($4.3 billion), and Endo ($450 million) are also pending. With the settlements totaling $54 billion, and comparing this to the estimated cost of the opioid epidemic in 2020 alone — $1.5 trillion with over 2.7 million fatalities — one has to ask: Is it sufficient? Is it just?

Indiana, Monroe County, and Bloomington settlements

Indiana filed their first lawsuits against opioid pharmaceutical manufacturers in 2018. At that time, an Indiana University study found that Indiana had sustained $43.3 billion in cumulative economic damage from 2003 to 2017. The study further anticipated that 2018 monetary damages would exceed $4 billion with continuing damages. From the current distributor’s settlement, Indiana has received $507 million.

The settlement mechanics are complicated. For Indiana to participate in the distributor’s settlement and to avoid using the default allocation suggestions by a bipartisan committee of state attorneys general, the state was required to accept one of three agreed formats: (1) a state-subdivision agreement in which a state reached a settlement agreement with the subdivisions (counties, cities, and towns) about allocation, distribution, and use of funds, (2) a statutory trust to receive funds and allocate to the state’s abatement accounts, and (3) an allocation statute, a state law that governs allocations and distributions.

Indiana opted for the third format, an allocation statute. House Bill 1193, now articulated in Indiana Code 4-6-15-4, laid out state agency involvement and metrics for distribution.

Each state’s share of the settlement was determined by the bipartisan committee by using existing data to determine how much each state and subdivision would receive. They examined the number of people with opioid use disorder reported to the National Survey on Drug Use. The county-level and national mortality data reported by HHS and the National Center for Health Statistics were used. Finally, the number of overdose deaths and the number of opioids shipped to a location, as collected through the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) ARCOS database, was also included.

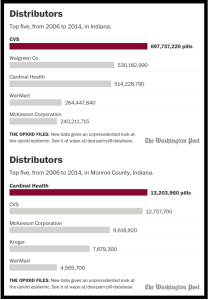

The Indiana Opioid Dashboard shows that Monroe County had 35 overdose deaths in 2022 and dispensed 130.9 opioid prescriptions per 1,000 population. In Indiana, data from ARCOS (Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System) show 2.8 billion pain pills dispensed between 2006 and 2014, with CVS alone distributing nearly 700 million pills, as reported by The Washington Post.

Top five distributors of pain pills from 2006 to 2014. (top) In Indiana, 2.8 billion prescription pain pills were dispensed from 2006 to 2014. (bottom) In Monroe County, 51.8 million prescription pain pills were dispensed, enough for 42 pills per person per year. | Source: U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s ARCOS data. Graphic by The Washington Post, used with permission.

In Monroe County, 51 million prescription pain pills were dispensed, enough for 42 pills per year for every person in the county. The biggest distributor, Cardinal Health, IU Health’s pharmacy distributor, dispensed 13.2 million prescription pain pills from 2006 to 2014. Compared to the $4.6 billion that Cardinal Health paid in the settlement, they recently reported $47.1 billion in fourth quarter earnings for fiscal year 2022. The company also claimed a tax loss of $974 million as a “net loss carryback,” a tax cut provision holdover from the coronavirus epidemic bailout.

Counties, cities, and towns (subdivisions) could opt in or opt out and pursue their own litigation. To opt in, cities, towns, and counties were required to accept the rules the Indiana statute laid out and allocations designated by the law.

Some subdivisions, like Bloomington, initially opted out in June 2021 to pursue their own litigation. According to Beth Cate, corporation counsel for the city of Bloomington, the initial reason for opting out was that the city believed the 50–50 distribution between the state and the subdivisions under the 2021 version of the code was inequitable to state subdivisions.

But in 2022, the Indiana legislature amended the opt-in deadlines and the initial allocation distribution between Indiana and the subdivisions to 30–70 percent, which incentivized additional subdivision participation. As a result, some of those subdivisions that had opted out opted back in, as Bloomington did in March 2022. By opting in, subdivisions surrendered any individual lawsuits against opioid distributors. Currently, 648 cities, towns, and counties across the state have opted in to the settlement.

For this first settlement, Monroe County and Bloomington have received two payments for 2022 and 2023, equaling approximately $635,000 and $531,000 respectively. Total amounts expected over eighteen years for Monroe County are $2.9 million and Bloomington $2.1 million, with attorneys’ fees included.

Douglas Huntsinger, executive director of NextLevel Recovery Indiana, says solutions funded by opioid settlement money “are best and most often best handled at a local level.” | Courtesy photo

The Town of Ellettsville will receive $172,261. According to Ellettsville’s Clerk-Treasurer Sandra Hash, they have not spent any money to date and will not pool their settlement funds with Monroe County or Bloomington. The Indiana Attorney General’s website lists all payments.

Under the 2022 amended version, Indiana Code 4-6-15-4, the 30–70 percent metric is broken down in the following manner: 15 percent of the funds are unrestricted use funds for subdivisions and the state. For instance, the state or a subdivision can opt to use their 15 percent to pay for anything that is non-opioid related.

The settlement agreement requires that 70 percent be spent on future opioid abatement measures. In Indiana, it is broken down as 35–35 percent. The 35 percent is restricted to payments for future opioid abatement programs and services throughout the state, distributed by the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA), and found in the Distributor Settlement Agreement in Exhibit E, List of Opioid Remediation Uses.

Counties, cities, and towns were allocated another 35 percent for future opioid abatement, as also seen in Exhibit E. As part of the negotiated settlement documents, Exhibit E acts as a guideline for states on how to spend settlement monies towards future opioid abatement measures.

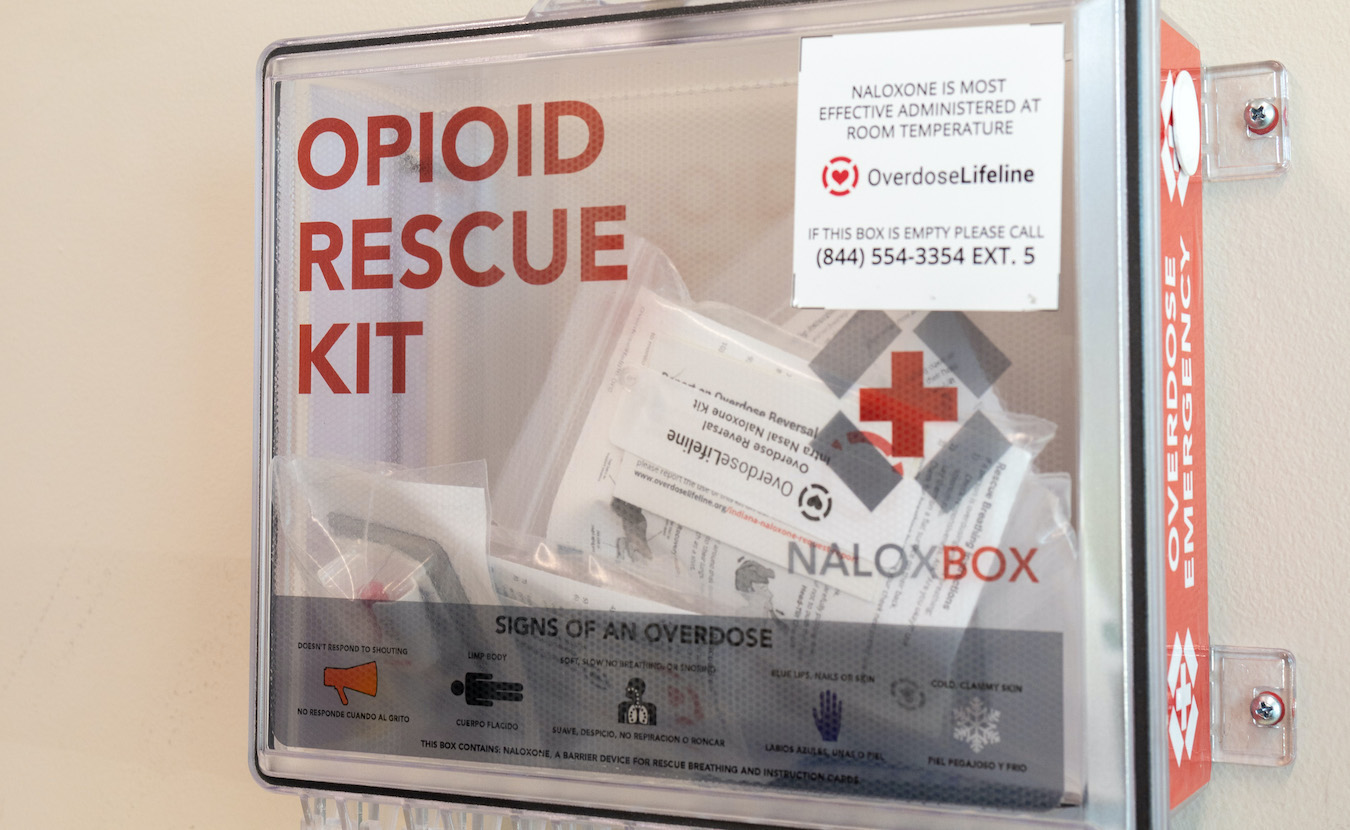

Subdivisions can use that money to pay for a syringe exchange program, naloxone supply boxes, or naloxone vending machines. For instance, a syringe exchange program allows substance use disorder users to exchange dirty needles for clean needles.

The Monroe County Health Department contracts with the Indiana Recovery Alliance to provide these services. According to Nick Voyles, Indiana Recovery Alliance executive director, they’ve given out more than 200,000 syringes since the syringe exchange programs started in 2016.

On March 14, 2023, the program received an additional $25,000 grant from the Syringe Services Fund of the Health Foundation of Greater Indianapolis to support that program. It supplied an additional 265,000 syringes.

But during an April 4 Bloomington city council meeting, Eric Spoonmore, president of the Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce, questioned how many syringes are in the public and if “we may have a glut of syringes.” Spoonmore raised the issue of public safety and the burden on law enforcement and EMT services of having used syringes in public places. City council did not address his concerns.

Indiana funds 430 NaloxBox units statewide. Stocked with naloxone, they are installed in public places to help reverse overdoses. The NaloxBox above is in the front entry of the IU Health Center, 600 N. Eagleson Ave., which is open 24/7. | Photos by Benedict Jones

Indiana funds 430 NaloxBox units statewide. They are stocked with naloxone (also known by the brand name Narcan), which can reverse overdoses, and are installed in public places. Recently, Gov. Eric Holcomb announced the first naloxone vending machine in St. Joseph County, the first of a planned nineteen machines around the state.

Lastly, all subdivisions have received two years of settlement monies for 2022 and 2023. They must complete annual reporting requirements to the state on how they used the settlement monies. “Settlement administrators have yet to provide these requirements,” says Huntsinger. “That’s one of the reasons why I think it is best that communities stick to the spirit of Exhibit E.” However, how they are supposed to do this is still up in the air.

Indiana too must report its spending to the taxpayers, and they have yet to publicly commit to reporting to the public how those monies have been spent by the subdivisions and by the state. According to NPR, Colorado created a public dashboard to show how funds were spent, and New Hampshire is posting their reports online. But how Indiana will publicly report how the money is spent has not been decided. “We have been in several discussions with other states, including Colorado, to identify best practices as we determine Indiana’s method of sharing reports with the public,” says Huntsinger.

David Bottorff, executive director of the Association of Indiana Counties, says a law proposed in the Indiana General Assembly would give subdivisions more leeway when using settlement monies. | Courtesy photo

According to David Bottorff, executive director of the Association of Indiana Counties, a proposed Indiana General Assembly law would give subdivisions more leeway when using settlement monies. Now referred to the Indiana Senate Appropriations Committee, HB 1208 would allow subdivisions to assign or transfer all or part of their payment to another city, county, or town to benefit both communities. They can also sell the right to receive a distribution. This means that if Stinesville, for example, wanted to assign its portion of the settlement monies to Monroe County for joint services, it could under this new proposed law.

“Some counties may want to hold onto that money for a little while and build up a cash reserve, so when they start a program, they have cash in hand,” says Bottorff. “A small town could [also] say, ‘We’re just going to go ahead and assign our benefits over to the county because of the small amount of money we’re going to receive over eighteen years.”

Master Tobacco Settlement Agreement

Why an Exhibit E? The settlement negotiators, a bipartisan group of 14 state attorneys general, worked to ensure opioid funds would be utilized for opioid services and programs to abate future opioid problems. The opioid settlements are often compared to the 1998 Master Tobacco Settlement Agreement (MTSA). In that agreement, less than 3 percent of the $246 billion settlement monies, spread over the first 25 years, was spent on tobacco prevention and cessation.

As reported in the journal Health Affairs, the difference between the opioid settlement agreement and the MTSA is that the opioid settlement prescribes restricted uses for the settlement monies, i.e., Exhibit E, whereas the MTSA did not. Pursuant to the MTSA settlement agreements, states had no requirement to use the proceeds for specific tobacco-related public health reasons, even though payments continue as long as cigarettes are sold in the U.S. In fact, in one state, they used the MTSA proceeds to reimburse tobacco farmers.

While the two settlements are vastly different, these learned lessons were folded into the opioid settlement agreements, hoping that such monies reduced future harm.

NextLevel Recovery Matching Grant

How will Indiana distribute the monies that they received? Recently, they used $25 million toward the FSSA’s NextLevel Recovery Matching Grant (NLRG) program where counties, cities, and towns could apply for a matching grant. For this grant, a subdivision’s opioid settlement money, funds from the federal American Rescue Plan Act, local general funds, private contributions, or philanthropy dollars could be pledged toward the grant. Shelby Thomas at NextLevel Recovery Indiana says they have received 72 applications totaling more than $93 million.

Monroe County Commissioner Penny Githens prepared the plan for the NextLevel Matching Grant for Bloomington and Monroe County. | Photo by Kristina Simmonds of White Birch Photography

Monroe County Commissioner Penny Githens prepared the grant plan for Bloomington and Monroe County. The grant requested more than $1 million in opioid services, including a harm reduction van for the Indiana Recovery Alliance, three crisis specialists, a transport sedan for Centerstone, various naloxone kits and boxes, and other harm reduction supplies. Cook Medical has also pledged $50,000 toward matching funds on the grant. The county has committed $335,000 toward the grant and an additional $50,000 for an NLRG grant submitted by Amethyst House. The awards will be announced on May 1.

The city will match that request with $100,000 of the opioid settlement monies received, says Beverly Calender-Anderson, director of the city’s community and family resources department (CFRD). That money will come from opioid settlement monies.

In addition, as per the city council meeting on April 4, 2023, the city approved an appropriation of $391,906 of opioid settlement funds for the following: $70,500 to supplement the CFRD’s Downtown Outreach Grant program, a housing program that addresses the increasing numbers of those experiencing homelessness and substance use disorder. A total of $221,406 will remain in the city budget for additional grants to community organizations that service those with substance use disorder and mental health issues.

Beverly Calender-Anderson is director of Bloomington’s community and family resources department and a member of the county’s Substance Use Disorder Awareness Commission. | Photo by Benedict Jones

What to do with the opioid settlement money and who should get it is the big question. First, for Monroe County and Bloomington alone, $5 million spread over eighteen years will never compensate for the expenses the city and county have encountered. So how should it be distributed within the county and Bloomington and who should be making these decisions?

While subdivisions have had sufficient warning that the settlement was coming, few counties proactively contacted substance use disorder and mental health providers, conducted a needs assessment, or established allocation metrics and rules. Why not?

“I think they wanted to wait until they received the first check,” says Bottorff. “We’ve been telling them for some time that some of it has been agreed to and that the distribution was forthcoming, but [it wasn’t] until the county started to receive that check in the hand, or payment in their account, did they feel comfortable about moving forward then starting to build.”

What other Indiana counties and cities are doing

Still, Huntsinger and Bottorff have been talking to counties, cities, and towns throughout the state for months through conferences and meetings, encouraging them to meet with stakeholders and ask what they need.

“Cities and towns within the county need to work together on how this will be spent,” Bottorff says, “because after you divide it out among 92 counties over eighteen years, if you don’t work cooperatively, you’re not going to get the biggest return on the investment.”

Opioid settlement money could help buy another van for the Indiana Recovery Alliance, as well as a transport sedan for Centerstone, naloxone kits and boxes, and other harm reduction supplies. | Photo by Benedict Jones

Some subdivisions are doing that. In Clinton County and its county seat, Frankfort, northwest of Indianapolis, local officials created a committee to conduct a needs assessment and align with Exhibit E.

According to Jordan Brewer, a Clinton County commissioner, their needs assessment looked at community demographics, specifically underserved and at-risk populations, existing services, and service gaps and barriers in the county.

“An opioid settlement committee was established by ordinance so that the group of representatives would be established for the life of the funding,” says Brewer. “We also established MOUs [memorandums of understanding] that will be signed annually from each department or entity that receives funding.”

Their key priority, however, was ensuring that individuals working on these issues in their community had input on how the committee could serve Clinton County residents.

Huntington County in northern Indiana has also formed a five-person oversight board with city and county representatives, a public health officer, a justice system official, and a person with a history of addiction.

“We wanted to ensure that there is representation from different backgrounds to ensure that we are thinking about the problem of substance abuse holistically,” says Dr. Matt Pflieger, Huntington County’s public health officer. “We also want to ensure a very transparent, efficient, and evidence-based process to get the money to organizations doing good work in our community.”

Huntington County, Huntington, and Warren have pooled their monies and placed them in a Community Foundation of Huntington endowment fund. “We are focused on granting money based on the attorney general’s guidelines, but specifically for prevention programs, groups involved in intervention of active drug use, and groups working in treatment,” says Pflieger.

In nearby Allen County, a ten-member coalition worked on a NextLevel Recovery Indiana Matching Grant. YWCA Northeast Executive Director Paula Hughes-Schuh was a coalition member. They have a residential crisis shelter for domestic violence survivors and a residential treatment center for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment.

This ten-member coalition included representatives of the Bowen Center Health Clinic, Parkview Behavioral Health, Lutheran Foundation, LSSI Works, Project ME, Recovery Café, a school care team, Connect Allen County, Purdue Fort Wayne, and YWCA Northeast. And while Allen County will not use the coalition to determine the distribution of settlement monies beyond the grant, Hughes-Schuh believes there is always room to collaborate better.

“If we don’t receive this grant, we might approach our units of local government in Allen County about supporting elements of this [coalition],” says Hughes-Schuh. “It’s building patterns that are just beneficial for the community.”

“

The irony in all this? The glaring omission of personal liability in settlement documents by those who led these practices.

”

While Monroe County and Bloomington were considering pooling their settlement monies and did pool their monies for the NLRG, conversations with stakeholders about how to spend the money overall have yet to happen, and conversations on the matching grant occurred with only a few select providers. Whether the county and city will be awarded the grant will be known on May 1.

As for spending on the remaining portions of the settlement monies or creating a committee/coalition that will address spending, according to Calender-Anderson, the city’s community and family resources’ director, “We haven’t talked to anybody.”

Few Indiana counties have proactively contacted mental health providers and organizations that address substance use disorder, conducted a needs assessment, or established allocation metrics and rules with regard to the settlement monies. | Photo by Benedict Jones

Bloomington city council member Isabel Piedmont-Smith confirms this. “I have not, and I don’t know of any council members who have had meetings with stakeholders, specifically on this topic.”

Even though it hasn’t happened to date, Piedmont-Smith believes it’s worth a try. “I think it would be a great idea to have a committee strategy on using these funds,” says Piedmont-Smith. “The committee certainly could include people from city government and county government and stakeholders, either service providers or people with mental health and addiction treatment specializations. I think it would be a very good idea, [though] I haven’t heard of any such thing happening.”

From a county perspective, Commissioner Githens says that she does talk to different SUD providers, though the extent to which she has specifically talked about how to spend current opioid settlement dollars is unclear.

There are existing mechanisms to do this. Calender-Anderson and Githens wonder if it is time for another opioid summit in Bloomington, something they have done in previous years. These opioid summits included various SUD and mental health service providers and stakeholders in day-long discussions. Still, it’s unclear if they will meet with stakeholders even though other counties have already made those plans and are moving forward.

The county Substance Use Disorder Awareness Commission (SUDAC) is a possible place for facilitating these conversations, says Calender-Anderson. She sits on that committee along with Githens, Voyles, and others. “I think that it would be a good role for them,” she says.

According to Githens, SUDAC is starting to plan an SUD summit for September 2024, which may involve other providers.

“I feel like we’re just getting started on this but have, on the city and county side, a lot of committed service providers,” says Calender-Anderson. “We needed to wait until we knew how much money was coming down and what it could be used for.”

What providers think

For some SUD and mental health service providers, it’s been challenging, though, to find out information about the settlement monies and what’s happening. Local providers are ready to talk, and their most basic request is simply to have more information about what is happening.

Jackie Daniels, director of clinical development at the Indiana Center for Recovery, says, “I wish that our process was really transparent.” | Photo by Benedict Jones

“I’ve read about [opioid settlements] at a national and state level, but I’m not quite sure who’s going to be the decision maker in Monroe County about the money,” says Jackie Daniels, director of clinical development at Indiana Center for Recovery. “I wish that our process was really transparent, and I’m curious what Monroe County’s process will be to determine how to best use the funds locally.”

She’s not alone. Centerstone’s vice president of adult services, Linda Grove-Paul, recently spoke with Doug Huntsinger, who explained numerous settlement points to her, she says. Even after talking to Huntsinger, Grove-Paul wonders what’s happening in her own county.

“If they don’t start to really align with what are our priorities in our community and talk to stakeholders, talk to providers, I mean, it’s really just a gap analysis, right? I think you need to have the grassroots people coming together and saying what we have. What do we need?”

Evidence-based harm reduction strategies

Still, how do Bloomington and Monroe County ensure that the allocation of settlement monies is equitable and fair, a condition Indiana has expressly required. “From my prior work experience looking at settlements and how they get distributed,” says Beth Cate, the city’s corporation counsel, “there’s a tension between identifying a lot of folks who would be worthy recipients of that money and not wanting to effectively dribble out the money in small quantities across such a vast landscape so that it doesn’t have any impact.” They are still in the early stages of decision, she says.

According to the website for NextLevel Recovery Indiana, the state identifies five guiding principles from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health to ensure the proper use of opioid settlement monies. Those guiding principles are:

- Spend the money to save lives

- Use evidence to guide spending

- Invest in youth prevention

- Focus on racial equity

- Develop a fair and transparent process for deciding where to spend the funds.

So when subdivisions opted into the settlement, they agreed to follow these principles. Language regarding transparency, evidence-based stakeholder input, and community investment are peppered throughout.

Linda Grove-Paul, Centerstone’s vice president of adult services, says, “I think you need to have the grassroots people coming together and saying what we have. What do we need?” | Photo by Benedict Jones

Providers believe that funding evidence-based practices is essential. “What we can do is put the money into evidence-based harm reduction strategies that show results or recovery,” says Voyles.

What are evidence-based harm reduction strategies? Research has shown that harm reduction strategies like clean syringes, medication-assisted treatments like methadone and buprenorphine, and fentanyl strips (which test the drug being used to see if it contains fentanyl) reduce overdose deaths. These are strategies that have worked consistently within the SUD community, reports the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

As identified in the John Hopkins guiding principles, developing a fair and transparent process for deciding where to spend the funds is critical to insure equitable and fair allocation. For Clinton County, a needs assessment helped ensure allocations were fair and equitable.

Mapping resources, gap analysis, metrics, or a rubric for allocation decision making will also help ensure fairness. The workgroup for the Monroe County Health Department’s Substance Use and Mental Health (SUMH) Community Health Improvement Plan has been working on these issues since July 2022.

This workgroup is developing an overall community health improvement plan for Monroe County that addresses the health needs of the county as a whole. Typically, these plans are done every three to five years in a municipality. The workgroup includes a number of SUD providers as well as the city and county administrations, Bloomington Police Department, Area 10 Agency on Aging, IU Health organizations, and others. Amy Meek leads the SUMH team.

They are currently in the process of mapping the current addiction and recovery resources and touch points by using the Taking Action Against Substance Use in Communities program fostered by Purdue University Extension.

“This process will help us to further identity gaps and needs to be shared with our elected officials to support possible utilization for opioid funding,” says Melanie Vehslage, senior community health specialist with the Monroe County Health Department. The workgroup has provided feedback to the county commissioner and county council members who, says Vehslage, have “direct control over the funding.”

Although Calender-Anderson is not aware of this group and its work, she is interested in what they are doing because, she says, “the results of the group may factor into how future opioid settlement funds are spend depending on what they find.”

As for the development of a rubric or a metric for ensuring equitable funding, she says, “It would be a really good idea for us to do that because [payments] go over eighteen years, and most of us are not going to be here in these positions eighteen years from now.”

Since 1999, states and communities have tried to keep up with the raging wave that’s the opioid epidemic. Even now, synthetic opioids like fentanyl and new drugs like xylazine (a veterinary tranquilizer) are driving up overdose rates, and even old favorites like methamphetamines are still on the streets and being mixed with fentanyl. These drugs can reduce the effectiveness of current harm-reduction methods like methadone or buprenorphine, making it harder to recover from addiction. With these increasing pressures, the temptation is that communities may use opioid settlement monies to turn to more stopgap measures instead of longer-term solutions.

But to providers, what matters is the long-term picture and efforts to solve infrastructure health problems. “I think that we have to start thinking foundationally,” says Julia Compton, executive director of Indiana Center for Recovery. “We need housing and jobs for people in early recovery so they can plan to care for themselves and their families. We deal with this stuff daily. We deal with the fallout with the families when someone relapses or someone relapses and passes away. I would really like to have a voice in some of this.”

Resources

Monroe County Health Department–Overdose Prevention and Naloxone

Indiana Center for Recovery

Bloomington Indiana Detox

Bloomington–Monroe County Substance Use Disorder and Recovery Resource Guide

Indiana Naloxone Boxes and Distribution Centers

Centerstone

Naloxone Boxes

overdoselifeline.org/naloxone-indiana-distribution/

Monroe County

Stride Center, 312 N. Morton St., Bloomington, IN 47404 | Photo by Benedict Jones

Indiana Recovery Alliance

118 S. Rogers St.

Bloomington, IN 47404

Kinser Flats

1610 N. Kinser Pike

Bloomington, IN 47404

Middle Path Collective

908 E. Sherwood Hills Dr., Sunny Slopes

Bloomington, IN 47401

Monroe County Correctional Center

301 N. College Ave.

Bloomington, IN 47404

Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard

1100 W. Allen St.

Bloomington, IN 47403

Peer Run Recovery Center

817 W. 1st St.

Bloomington, IN 47403

Recovery Engagement Center

221 N. Rogers St.

Bloomington, IN 47404

Stride Center

312 N. Morton St.

Bloomington, IN 47404

Brown County

Do Something Inc.

153 E. Gould St.

Nashville, IN 47448

Launch House

153 E. Gould St.

Nashville, IN 47448

St. David’s Episcopal Church

11 W. State Road 45

Beanblossom, IN 46160

Owen County

Centerstone

35 Bob Babbs Dr.

Spencer, IN 47460

Owen County Health Department

751 E. Franklin St.

Spencer, IN 46760

Spencer Lions Club

9 N. Main St.

Spencer, IN 47460

Greene County

Family Life Center of Greene County

2093 W. State Road 54

Bloomfield, IN 47424

Lawrence County

Centerstone

1315 Hillside Rd.

Bedford, IN 47421

Oolitic Fire Department

5 Hoosier Ave.

Oolitic, IN 47451

Momentum Community Church

1403 R St.

Bedford, IN 47421

Recovery Engagement Center

1129 16th St.

Bedford, IN 47421

Tabernacle of Praise Church

1381 US Highway 50

Bedford, IN 47421

Morgan County

Centerstone

952 S. Main St.

Martinsville, IN 46151

First Christian Church

89 S. Main St.

Martinsville, IN 46151

Jackson County

Beauty From Ashes

303 Pennsylvania Ave.

Crothersville, IN 47229

Johnson County

Johnson County Public Library Trafalgar Branch

424 S. Tower Dr.

Trafalgar, IN 46184

Clay County

Cataract Lakeside Grocery Store

10710 Boat Dock Rd.

Poland, IN 47868

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate

The award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB and Limestone Post Investigate” is a journalism collaboration between WFHB Community Radio’s Local News Department and Limestone Post Magazine. Deep Dive debuted in February 2023 as a year-long series, made possible by a grant from the Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County. The Community Foundation also helped secure a grant from the Knight Foundation to extend the series for another year.

In the series, Limestone Post publishes an in-depth article about once a month on a consequential community issue, such as housing, health, or the environment, and WFHB covers related topics on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. during its local news broadcast.

In 2023, Deep Dive was chosen by the Institute for Nonprofit News as a finalist for “Journalism Collaboration of the Year” in the Nonprofit News Awards held in Philadelphia. And this year, the series brought home seven awards from the “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest by the Society of Professional Journalists. Read more about the awards.

Here are all of the the Deep Dive articles and broadcasts so far:

Housing Crisis

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published February 15, 2023:

Deep Dive: Struggling with Housing Supply, Stability, and Subsidies, Part 1

WFHB reports:

Steve Hinnefeld won 1st place for “Non-Deadline Story or Series” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for parts 1 and 2 of this housing series. The staff of WFHB won 2nd place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” for its programs “Deep Dive: Housing Crisis.”

Housing Crisis Solutions

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published March 15, 2023 | photography by Jim Krause

‘No Silver Bullet’: Advocates, Officials Use Many Tactics on Housing Woes

WFHB reports:

Opioid Settlement Fund Investigations

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published April 12, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

How Will Opioid Settlement Monies Be Spent — and Who Decides?

WFHB reports:

IU Tree Inventory

Limestone Post article by Laurie D. Borman, published May 17, 2023 | photography by Jeremy Hogan

Trees Do More Than Add ‘Charm’ to IU Campus

WFHB reports:

Indiana Power Grid

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, published June 21, 2023 | photography by Benedict Jones

The Power Struggle in Indiana’s Changing Energy Landscape

Rebecca Hill won 1st place for “Medical or Science Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Lake Monroe Survival

Limestone Post article by Michale G. Glab, published August 16, 2023 | photography by Anna Powell Denton

How Healthy Is Lake Monroe — and How Long Will It Survive?

Michael G. Glab won 3rd place for “Business or Consumer Affairs Reporting” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Indiana Lawmakers Attack Public Schools

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, published September 13, 2023 | photography by Garrett Ann Walters

Local Parents, Educators Face ‘Attack’ on Public Schools from Indiana Lawmakers

WFHB reports:

On Saving the Deam Wilderness

Limestone Post photo essay by Steven Higgs, published October 18, 2023

On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay

Steven Higgs won 2nd place for “Multiple Picture Group” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this photo essay.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 1

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photography by Olivia Bianco, published December 18, 2023

One Emergency from Catastrophe: Who Struggles with Food Insecurity?

Christina Avery and Haley Miller won 1st place for “Coverage of Social Justice Issues” in the Indiana Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists “Best in Indiana” Journalism Contest for this article.

WFHB reports:

Food Insecurity, Part 2

Limestone Post article by Christina Avery and Haley Miller, photos by Olivia Bianco, published March 13, 2024

‘Patchwork’ of Aid for Food Insecurity Doesn’t Address Its Cause

WFHB report:

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands

Limestone Post article and photos by Anne Kibbler, published May 15, 2024

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?

WFHB reports:

- Wetlands (Part 1), May 22, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 2), May 29, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 3), June 7, 2024

- Wetlands (Part 4), June 12, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

Limestone Post article by by Brookelyn Lambright, Karl Templeton, and Brenna Polovina from the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism, published August 1, 2024

Resilience Amid Hardship: Refugees Find Challenges, Opportunities in Bloomington

WFHB reports:

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 1), August 7, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 2), August 14, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 3), August 21, 2024

- Refuge in Indiana (Part 4), August 28, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

Limestone Post article by Steve Hinnefeld, photography by Benedict Jones, published September 24, 2024

Apprenticeships Work for Some High School Students But Not All

WFHB reports:

- Apprenticeships (Part 1), October 9, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 2), October 16, 2024

- Apprenticeships (Part 3), October 30, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

Limestone Post article by Haley Miller, published November 26, 2024

Goal of BPD and Social Support Team Is ‘To Help People’

WFHB reports:

- Police and Social Work, January 29, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 2), February 5, 2025

- Police and Social Work (Part 3), February 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

Limestone Post article by Marjorie Hershey, photos by Jeremy Hogan/The Bloomingtonian, published January 26, 2025

Political Polarization Hurts Communities — What Can Be Done?

WFHB reports:

- Political Polarization, (Part 1), March 19, 2025

- Political Polarization, (Part 2), March 27, 2025

- Political Polarization, (Part 3), April 2, 2025

Mental Health Issues Are Increasing Dramatically Among Hoosier Youth

Limestone Post article by Rebecca Hill, photography by Benedict Jones, published April 3, 2025

Mental Health Issues Are Increasing Dramatically Among Hoosier Youth

WFHB reports: