[Publisher’s note: This article by Jim Allison on proportional representation is part of Limestone Post’s coverage for Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative of news outlets to report on threats democracy is facing in the U.S. — at the local, state, and national levels. More about Democracy Day, and more of our coverage, are at the end of this article.]

Bill: Hey, Jack.

Jack: Hey, Bill. What’s new?

Bill: Say, Jack, have you bought any gas lately?

Jack: Gasoline? No. Not lately. Why?

Bill: Well, this morning I pulled up at my usual pump, and guess what? The attendant said the price of my gas would depend on what party I had voted for.

Jack: No way! There ought to be a law!

Bill: That’s the trouble. There is a law. The state just passed a law saying that from now on, one party’s voters would pay four dollars a gallon, and the others would pay six!

This is pure fantasy, of course, when it comes to the price of gasoline. But it is not far from the truth when it comes to Indiana’s elections for Congress and the state legislature. If you were to delve into the question of how many seats your vote “buys” in the U.S. House of Representatives, the Indiana Senate, or the Indiana House of Representatives, surely the answer should not depend on what party you voted for. Isn’t that what we mean by the “one-person, one-vote rule,” by the “equal protection” clause of the 14th Amendment, by “small d” democracy? Every person’s vote counts the same as any other person’s vote?

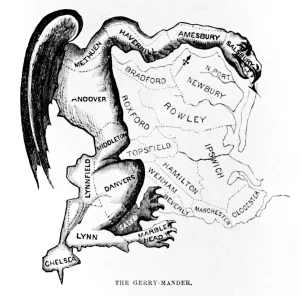

The term “gerrymander” comes from this 1812 Gilbert Stuart cartoon of a Massachusetts electoral district twisted beyond reason. Political parties gerrymander voting districts to guarantee their voters carry more weight per capita than the opponent’s voters.

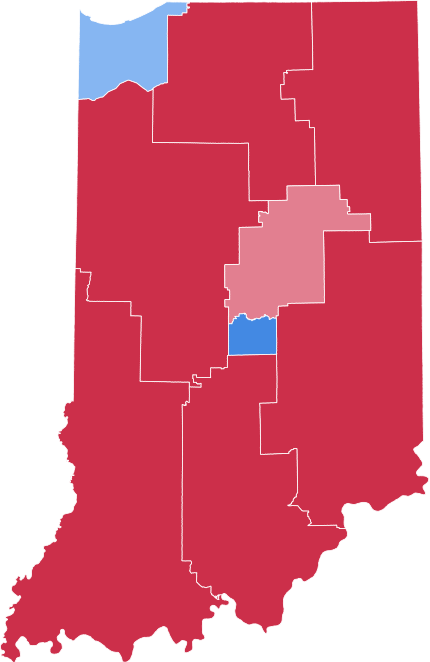

Of course. But in the redistricting done in 2011 and 2021, our state legislature violated those principles by means of partisan gerrymanders: three new district election maps drawn to guarantee that one party’s voters carried more weight per capita than the opponent party’s voters. That is why Indiana’s nine delegates to the U.S. House of Representatives now comprise seven members of one party and only two of the other. This means that about 55 percent of Hoosier voters have been picking about 78 percent of our representatives in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Had proportional representation held sway, the split would not be 7–2, but 5–4. Similar violations of one person, one vote are apparent in the two houses of our bicameral state legislature. And they are nothing new. In Indiana’s 1982 midterm elections for the state legislature, Democrats won 52 percent of the popular vote but won only 36 percent of the seats in the state senate and 43 percent in the house.

Some readers might like to see our gerrymanders for themselves. That’s what I had in mind in 2019, when I googled the Indiana Secretary of State for the official election results of our 2018 elections. I used those numbers to calculate for each major party its proportion of the popular vote and its corresponding proportion of seats won in the state legislature and Congress.

In each of those three elections, I found the same pattern reported by Nick Seabrook in his book One Person, One Vote: A Surprising History of Gerrymandering in America (Pantheon, 2022). Additional tests persuaded me that each of those three partisan differences was statistically significant: On average, one party’s voters carried significantly more weight per capita than the other party’s voters in the selection of our legislators. This is not one person, one vote. This is somebody’s vote counts more than somebody else’s vote.

What might we do to equalize the value of our votes? Perhaps the first step is to understand who got them so far out of whack.

Due largely to election districts gerrymandered by a group of Indiana legislators, since 2012 Republicans have been elected to seven of the nine Indiana seats in the U.S. House of Representatives — 78 percent — while receiving only 55 percent of the votes. This practice continues despite Article 2, Section 1, of the Indiana Constitution requiring “All elections shall be free and equal.”

In Indiana, a group of state legislators are responsible for the three district election maps drawn after the national census every 10 years: one for Congress, and two for our bicameral state legislature. Both major parties figure in this process, but the majority party holds the upper hand. And the way to give your party’s voters more weight per capita than the other party’s voters is to pack a relatively large number of the other party’s voters into a relatively small number of districts. As a result, the other party will score relatively big wins, but few of them, while your party scores smaller wins but lots of them. That is how the party that controls the drawing of the maps can win more legislative seats per capita than the opposition, in violation of the one-person, one-vote rule.

Partisan gerrymanders harm many individual voters by diluting their votes, but they harm more widely by making elections less truly competitive. When people catch on that the game is rigged, why should they bother to vote? Guaranteed a safe seat, why should your “representative” pay any attention to you? This is no way to run a representative government.

In Indiana, both major parties have engaged in this kind of partisan gerrymandering at one time or another. But with the advent of computer technology and the help of hired experts, the practice has grown to alarming proportions. An extreme example is Wisconsin, where less than half of the popular vote has been seating a supermajority of the legislature. In Indiana the big change happened in 2011, when our maps produced big partisan gerrymanders that were replicated in 2021.

So, those who oppose partisan gerrymanders should let their representatives know that they strongly favor reform of the three current maps for Congress and the state legislature. Some states, such as North Carolina, have already been ordered by state courts to reform their 2021 maps. The situation in that state is volatile, and may remain so for some time. But we should let our representatives know that a good-faith effort toward reform would not go unrewarded.

Another promising avenue is the ranked-choice voting method pioneered by election experts in Maine, Alaska, and many major cities, but that is a topic for another article.

No citizen moved to join this struggle against the partisan gerrymander needs to work alone. There are plenty of nonpartisan organizations that would welcome your help. To name just three: Common Cause Indiana, All IN For Democracy, and League of Women Voters of Indiana.

Visit the Indiana Voter Portal at indianavoters.in.gov to register to vote, check your voter status, vote by mail, find your polling location, and more.

When all is said and done, it’s up to us to make good on Article 2, Section 1, of our state Constitution: “All elections shall be free and equal.” Right now, Indiana’s gerrymandered elections for Congress and the state legislature are far from equal.

We would never tolerate such treatment at the gas pump. Why do we tolerate it at the ballot box?

Democracy Day

Limestone Post is participating in Democracy Day, September 15 , a nationwide collaborative of news outlets that are reporting on threats democracy is facing in the U.S. — at the local, state, and national levels. The goal of Democracy Day, which coincides with the United Nations’ International Day of Democracy, is to draw attention to this crisis and provide citizens with the context and information they need to fight ongoing anti-democratic actions and policies.

Limestone Post is participating in Democracy Day, September 15 , a nationwide collaborative of news outlets that are reporting on threats democracy is facing in the U.S. — at the local, state, and national levels. The goal of Democracy Day, which coincides with the United Nations’ International Day of Democracy, is to draw attention to this crisis and provide citizens with the context and information they need to fight ongoing anti-democratic actions and policies.

This series also supports Limestone Post’s focus on solutions journalism: rigorous, evidence-based reporting that looks at efforts to solve problems. Solutions journalism does not just report on problems; rather, it focuses on how people are responding to problems. And it ensures readers have access to the information and tools needed to build an equitable and sustainable community.

Read more of Limestone Post’s coverage for Democracy Day:

Sheila Kennedy: Civic Literacy Is ‘Critical’ to a Functioning Democracy

Sheila Kennedy: Civic Literacy Is ‘Critical’ to a Functioning Democracy

by Sheila Suess Kennedy

Sheila Suess Kennedy, Emerita Professor of Law and Public Policy, says that when people don’t understand the most basic premises of our legal system, our public discourse is impoverished and ultimately unproductive. “Unfortunately,” she writes, “that civic knowledge is in very short supply.” Click here to read the article.

Voting Guide by League of Women Voters of Bloomington-Monroe County

Voting Guide by League of Women Voters of Bloomington-Monroe County

by Debora Shaw

The League of Women Voters of Bloomington-Monroe County has created this quick-reference guide on voter registration, voting by mail, and various voting requirements. This is the first in a series of articles on civic engagement produced by LWV for Limestone Post. Click here to read the guide.

How Redistricting Congressional Districts Can Undermine Majority Rule

How Redistricting Congressional Districts Can Undermine Majority Rule

by Marjorie Hershey

“In a democracy, voters choose their political leaders. In a democracy that permits gerrymandering, elected leaders choose their voters.” Marjorie Hershey, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Indiana University, wrote this in an article for “The Conversation,” an independent news organization. She has updated the article for Limestone Post. Click here to read her article on redistricting.