“Within the visiting, the trust required to become vulnerable is forged.”

—Megan Snook

Being a photojournalist and anthropologist, I have walked through life a voyeur, observing the cultures and landscapes that shape people. Beginning that journey as a film photographer, I have traveled the world documenting the lives of people from all walks of life. From stopping to have a cup of tea on the streets of Africa to calling the mares in from pasture in western Kansas to welcoming people into my Bloomington studio, I have learned that everyone has a story to tell, and nothing tells that story better than the eyes.

As the industrial revolution sped past, leading us into modern day capitalism, the old ways of doing things have seemingly disappeared. Trades requiring artistic expertise, patience, and practice have been exchanged for quicker processes that produce faster results. Photography has held such a fate. Digital photography and AI have eliminated much of the tangible artistry demanded by early photographers. Years-long apprenticeships have been traded for online courses. A photographer — once required to possess an artistic eye, a solid understanding of chemistry, and the instinctive grit required for navigating a life on the road — can now easily manipulate a photograph from the comfort of their desk chair.

A brief history

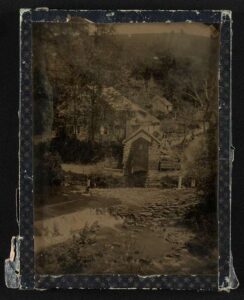

This 1858 photograph is one of the earliest tintypes and shows Thomas Livezey’s mill and house, alongside Wissahickon Creek in Glen Fern, Pennsylvania. | The Americana collection of Marian Sadtler Carson, Library of Congress

As the 19th century was an age of scientific advancement, ideas and technologies spread like wildfire in the photographic community. The tintype was born out of various attempts by great scientists and amateur chemists to improve earlier forms of photography.

Frederick Scott Archer, an Englishman, invented the wet plate collodion process in 1851. This process was an improvement upon the daguerreotype, which used a silver-plated copper sheet and was not financially attainable for most people. Archer coated glass plates in a viscous chemical compound known as collodion, which was then soaked in a silver nitrate bath, producing what were known as ambrotypes.

In 1853, a Frenchman by the name of Adolphe-Alexandre Martin presented an improvement upon the wet plate process to the Académie des Sciences in Paris. Martin’s process utilized a copper sheet or a piece of cardboard coated with black varnish, as opposed to glass sheets, making the photographs more portable and inexpensive.

After experimenting with Martin’s process, Hamilton Lanphere Smith discovered that baking varnish onto a thin iron sheet helped create an extremely durable and consistent product. In 1856, Smith patented his invention in the United States, and through the culmination of this transatlantic chain reaction, the tintype was born.

With the advent of the tintype, for the first time in history, the average person could have their likeness reproduced. Photographers began setting up studios and traveling to rural locations, making portraits of people who had likely never seen a camera. Operating out of covered wagons, photographers could now document historical events and landscapes, creating a record of visual history unlike anything that came before. Loved ones could now forever cherish images of the people they held most dear.

The process

Megan Snook with her tintype camera. Cameras used in tintype photography are often large-format field cameras that use plates measuring 4×5 or 8×10 inches. A tripod is used to steady the camera during the long exposure process. | Courtesy photo

It’s hard to imagine, in this modern day, that a process as cumbersome as the wet plate collodion technique could be considered revolutionary. The creation of a tintype begins with a metal sheet coated in a black varnish. This black surface is then coated with a chemical wet plate photographers refer to as “collodion,” because its main ingredient is raw collodion (a syrupy nitrocellulose solution). There are various recipes for collodion, each differing in their benefits, ranging from shelf life to sensitivity. These recipes have been passed down generationally and include names like “Old Workhorse” and “Old Dead Bride.” Generally, a collodion recipe is created by dissolving metal salts into ether and alcohol and combining them with raw collodion. That mixture is, in essence, a fast-drying glue that binds to the plate. The plate is then soaked in a bath of silver nitrate, where silver particles adhere to the collodion and make the plate sensitive to the light. One must work in the dark at this point, as any exposure to the light will ruin the plate. The plate is then transferred to a special light-tight carrier that fits into the back of the camera. The plate is now ready to be exposed.

Having prepared the sitters for their portrait and focusing the lens, the photographer takes the prepared plate to the camera and exposes it to light from the image being carried through the lens. The exposure time is much longer for the wet plate process as compared to a modern camera. Sunlight is valuable as a powerful light source because tintypes require an incredible amount of light. Many tintypists today use high wattage studio lights; however, this technology was not available during the mid-19th century.

After the photograph has been exposed, the plate is returned to the darkroom for development. It is essential not to overdevelop a tintype since it could easily be ruined. Consistency in development time is key: It lessens the likelihood of overdevelopment and eases troubleshooting if an issue arises. Once the image is developed, the effects of the development bath are stopped by washing the tintype in water. At this point, the image is no longer sensitive to the light. Next, the tintype is then transferred to a “fix tank” where excess silver halides are removed, and the image comes to life. Afterward, the tintype is washed thoroughly and dried.

The tintype is now extremely fragile — any slight graze could ruin the image, requiring one to start again. Varnishing is essential to the preservation of a tintype. Varnish is made by dissolving a resin known as gum sandarac in grain alcohol and lavender oil. Once the plate is coated in varnish, it is baked and then left to cure for up to two weeks. Now the process is complete and tintype is ready to be returned to the sitter.

“

Early forms of photography required not only an artist’s eye but also a solid understanding of chemistry and the instinctive grit required for navigating a life on the road.

”

Successfully navigating every step in the process is essential to a positive final result. Many variables are at play throughout the process, and any slight mistake could result in needing to remake the image. Temperature, humidity, light, the sitter’s ability to remain motionless, and the age of the chemistry (some of the chemistry must be properly aged for consistent results) are all factors that contribute to the outcome of the image. The ability to stay calm and troubleshoot every scenario is fundamental in successfully producing a quality tintype. The wet plate collodion process is extremely finicky and takes years of practice to perfect. The mistakes one makes are the greatest teachers in this undertaking. The lessons can be painful, meaning the artist is likely to never suffer them again.

Slow process, intentional life

Life as a documentary photographer was fast paced, and I found myself at the whim of whomever I was chronicling. Constantly, I was aware of any minute shifts in my surroundings and would jump into the wind at the notion of any new or exhilarating experience. Those subtle nuances seemed to continuously lead me to the next great photograph, and against all odds I refused to miss an opportunity. Home was wherever I was, for whatever amount of time I was there, and living out of a suitcase was my norm.

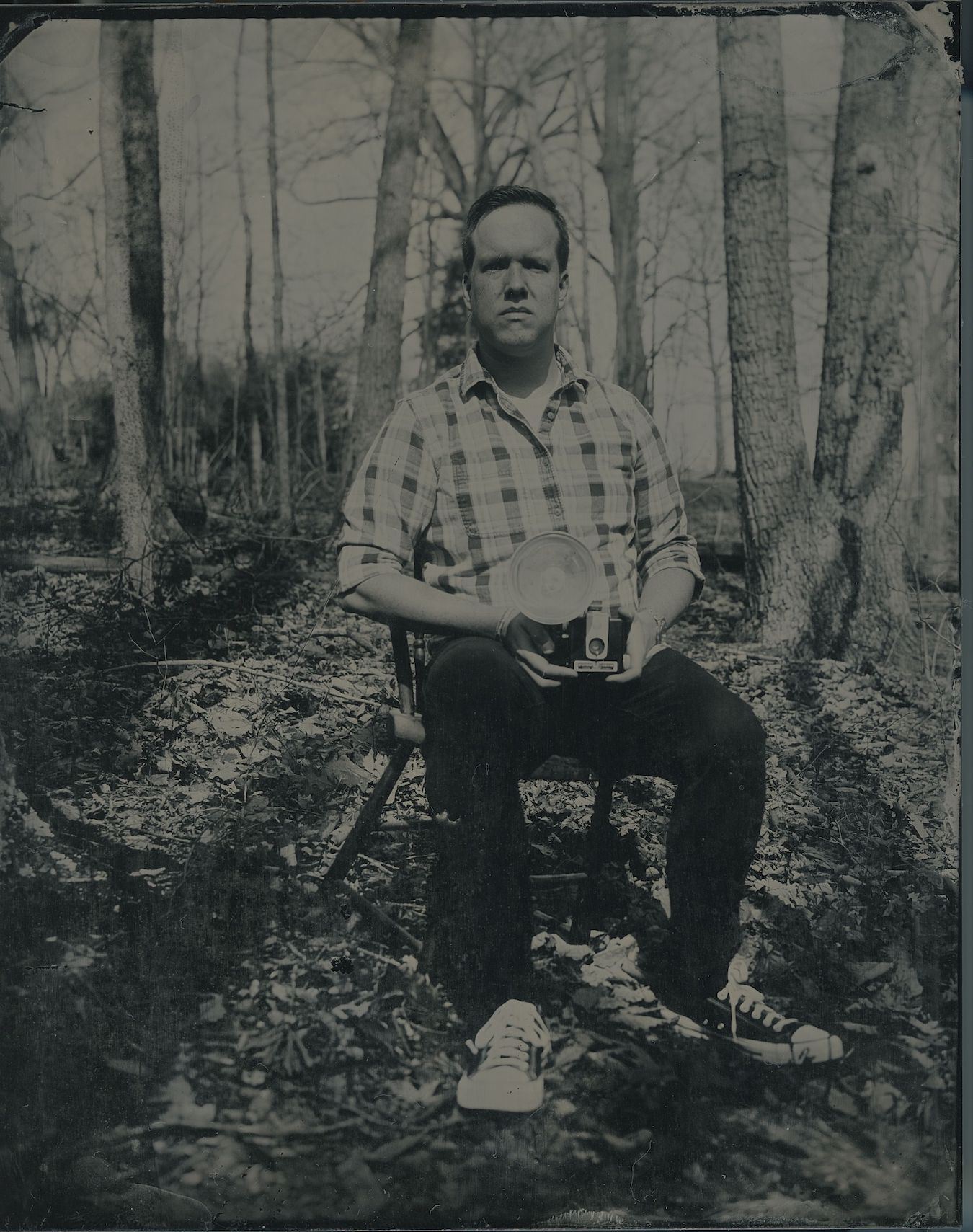

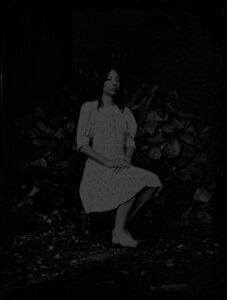

Megan Snook, Self-portrait. Bloomington, Indiana, Mother’s Day 2024

Seven years ago, I became a mother, and my way of life changed drastically. Motherhood forced me to slow down and remain still within my home and within myself. The days became gentle as I spent years observing my daughter’s growth and the constant flux the seasons brought to our tiny homestead, which had become the backdrop of our lives. Watching the endless change that can happen outside of a singular window nurtured an appreciation within me for the beauty that rests in any given moment, no matter how still that moment may be.

During these years, my desire to live a fast life deteriorated. I became committed to creating a life centered around the home and a way to raise my daughter among the trees, alongside continuing my work as a photographer. I yearned for a way to support my family that didn’t involve jumping into the rat race and consenting to having others raise my child.

My prayer was answered when I journeyed to West Virginia for a wet plate photography workshop in 2021. During that magical weekend, the path forward became clear. I was determined to document people through the lens of much slower times. The wet plate process is deliberate and grants the time that is essential for exchanging stories and perhaps a cup of tea, allowing subjects to become comfortable within themselves so they may be captured as they truly are.

Inviting people to my home studio has become one of the greatest joys of my life. Welcoming folks into my home allows them to become acquainted with me on a very intimate plane. Seeing the remnants of breakfast on our stove, petting our dogs, or telling me how they take their coffee somehow eases their desire to mask the true nature of their being. It lessens the intimidation of being viewed through the mechanical eye of a lens, a lens perhaps without empathy. Within the visiting, the trust required to become vulnerable is forged. It is within that space that an honest likeness can be constructed. It is within that moment that the eyes become willing to tell the wholeness of the story.

Becoming a tintypist has created a means for me to live an intentional existence. Constructing a livelihood within a structure that honors all the things that make life sweet has transformed my way of life. I believe it is within these thoughtful ways of existing that we can truly change the world, however small that change may be. Reviving the tintype has ignited within me an appreciation for a slow way of living. In keeping with the old ways, in keeping in time with the earth, I am better able to appreciate the things that are most precious in this life.

See more of Megan’s photography at ThePeople’sPortraiture.com and her Instagram page.

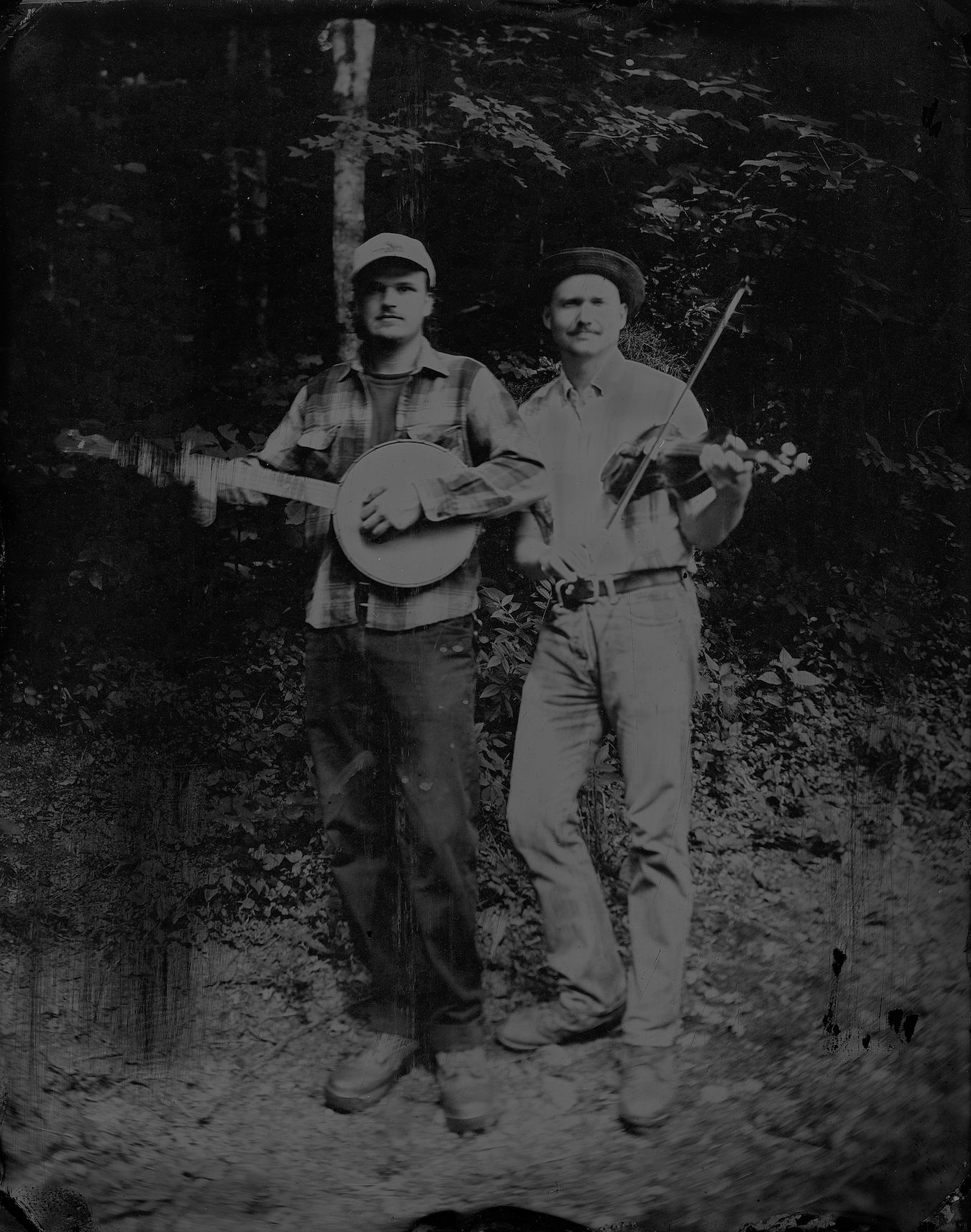

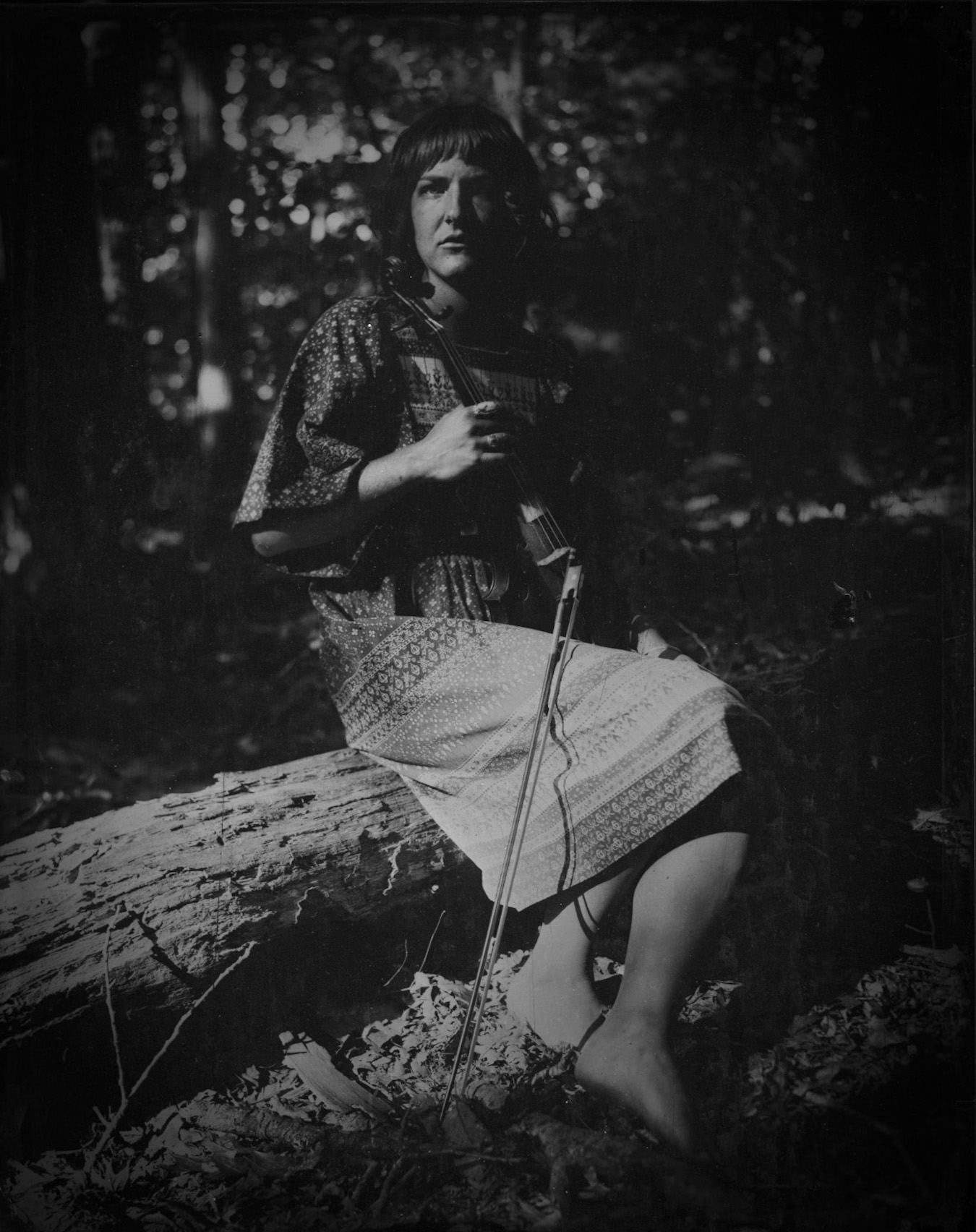

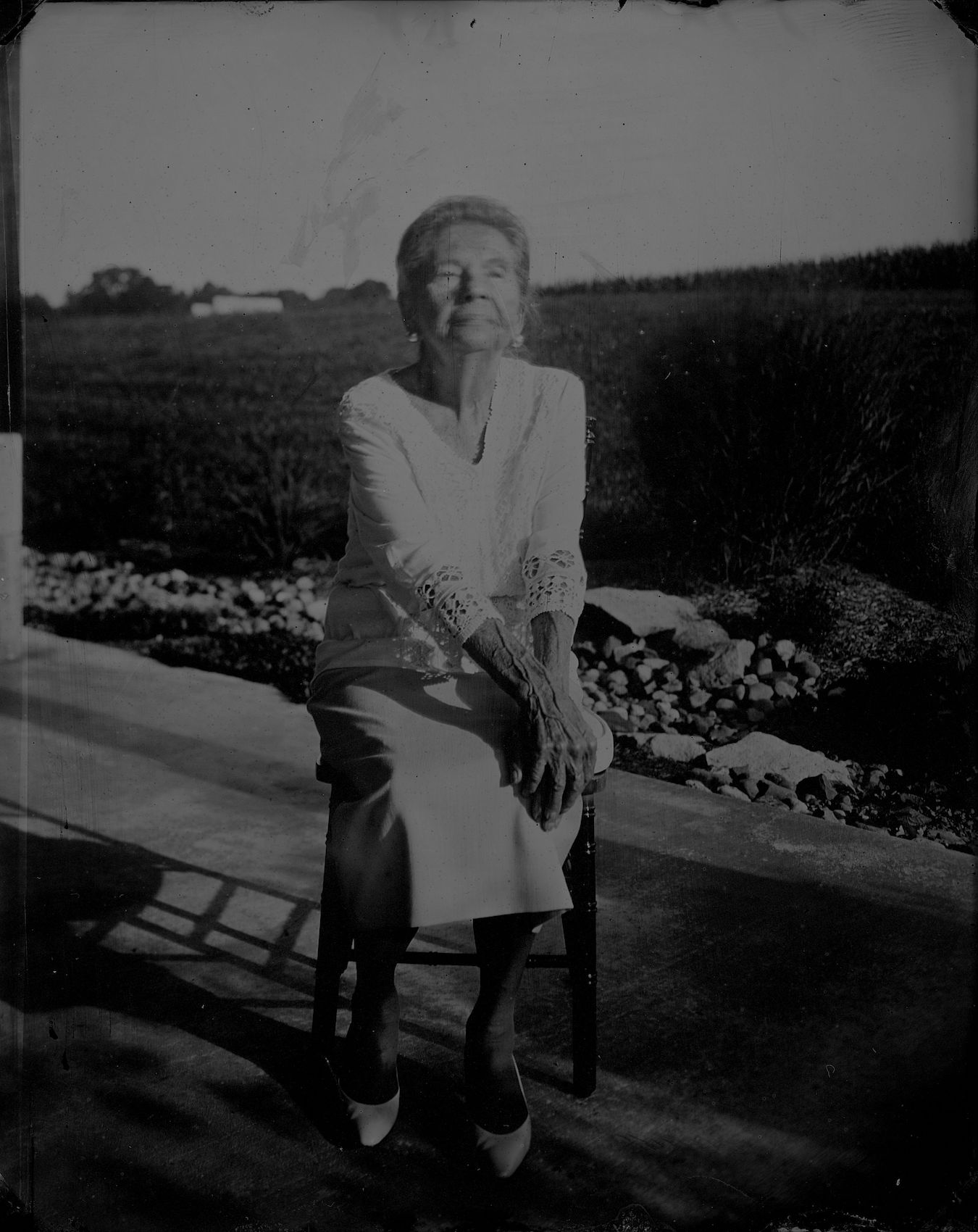

Tintypes by Megan Snook

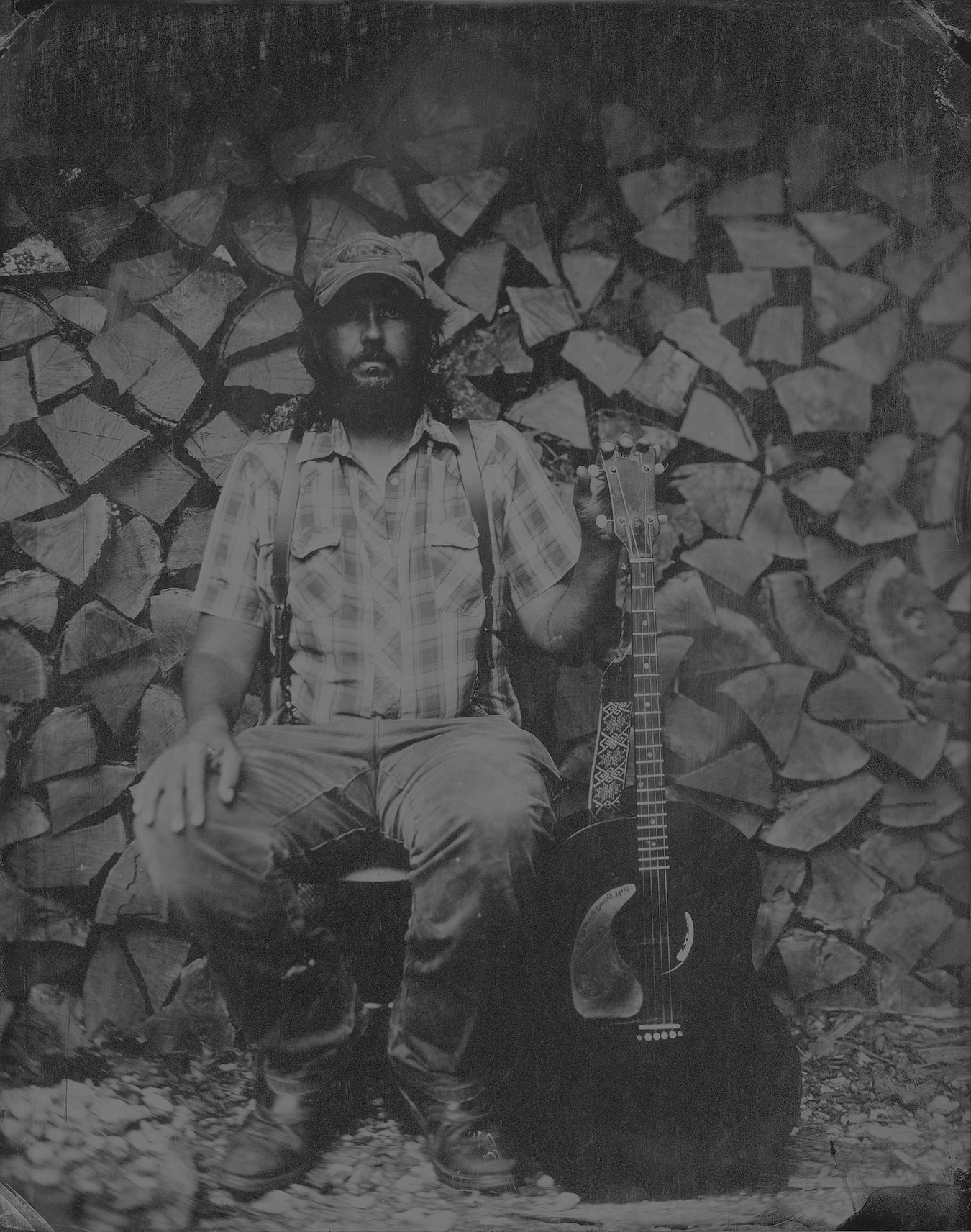

- Abe Partridge. Woodshed, Persimmon Ridge, Bloomington, Indiana, December 7, 2023

- The Alexanders. Chicken Coop, Persimmon Ridge, Bloomington, Indiana, May 20, 2023

- Donnie Parker with axe. Clay County, Kentucky, September 8, 2023

- Bedel and Hubbard. Elliot County, Kentucky, July 8, 2023

- Emilie Rose. Persimmon Ridge, Bloomington, Indiana, September 15, 2023

- Grandma Kay. Whippoorwill Hill, Bloomington, Indiana, August 26, 2023

- James Seaver. Persimmon Ridge, Bloomington, Indiana, March 10, 2023

- Johno Leeroy. Woodshed, Persimmon Ridge, Bloomington, Indiana, June 22, 2023

- Kay. Whippoorwill Hill, Bloomington, Indiana, August 26, 2023

- Linda Jean Stokley. Persimmon Ridge, Bloomington, Indiana, August 26, 2023

- Margo Price. Lexington, Kentucky, September 10, 2023

- Lila Simpson. Clay County, Kentucky, September 10, 2023

- Noelle Sosaya and lover. Cold Beer, New Mexico, August 12, 2023

- Stephanie Duckworth. Elliot County, Kentucky, July 8, 2023

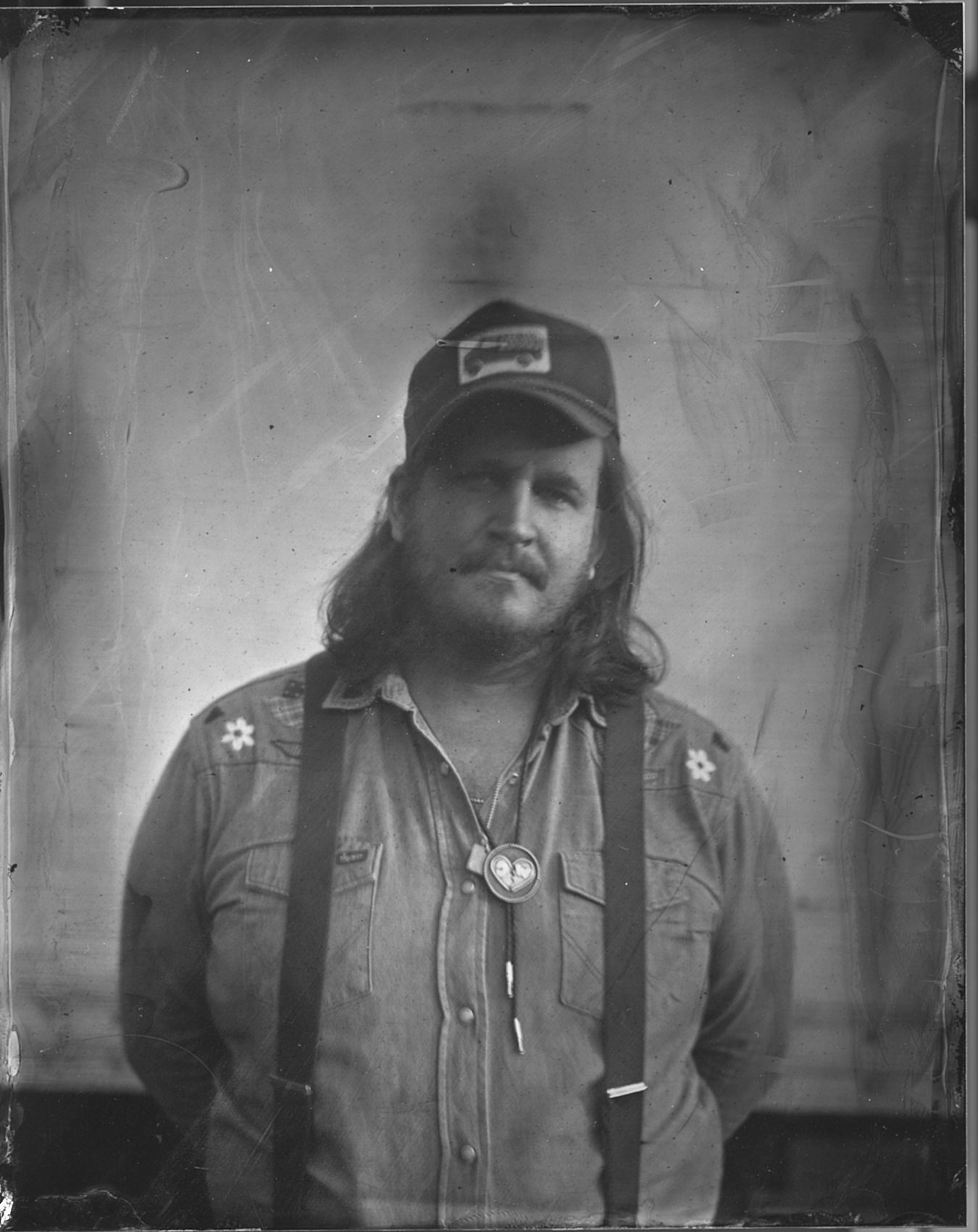

- Willi Carlisle. Indianapolis, Indiana, February 24, 2023

View more photo galleries on LP

Photo by Jeff Danielson

See the photography of Megan Snook, Matt Brookshire, and Jeff Danielson in an article by Erin Hollinden: “Three Local Photographers Share Motivations, Techniques, Photos”

“A Half-century Trail from Beanblossom Bottoms to the Colombian Amazon,” by Steven Higgs

“Antique Machinery Club Keeps Tractors — and History — Alive,” story by Dason Anderson, photos by Limestone Post

“On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest | Photo Essay,” by Steven Higgs

“The Murals of Bloomington — Photos and Trail Map,” photography and story by M.J. Bower

Adam Reynolds with his 4×5 field camera. | Limestone Post

Photography by Adam Reynolds, including photo essays on his three-part series, “‘Places, Things, People’ 4×5 Gallery”

“6 Things You Didn’t Know About the Jordan Greenhouses” (now called the Biology Building Greenhouses), article by Jen Hockney Bratton, photography by Lynae Sowinski

“Photographer Shoots Bloomington Street Scenes on Film,” photography by Justin Banks

“These New Photos Show Rooftop Is Inaccessible But Not Destroyed,” photography by Lynae Sowinski

“From Lake Monroe to the Milky Way, a Photographer’s Long Exposures,” photography by Nathan Clark