These are the stories of three local photographers in different phases of their lives and careers. Matt Brookshire — grooving bass player whose professional life is in transition — snaps mostly landscapes and is still learning technical tools. Megan Snook — entrepreneur, anthropologist, and journalist — has made tintype photography her business. Jeff Danielson — soccer player, hiker, and former restaurateur — photographs mostly birds and nature and has developed expertise in both shooting and editing. And all three started photography when they were young, have remarkable backgrounds, make their homes in Monroe County, and seek to reveal what’s unique and meaningful in their subjects. They shared their motivations, techniques, and images for this special Limestone Post online exhibit.

“I’ve learned that I will take 600 or 700 pictures of one thing, and in the end, most often, the first or second shot is the best.” —Matt Brookshire

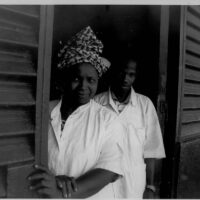

“I enjoy observing people and understanding from where they came and how that has led them to be the people that they are. What was their culture and their landscape? How did all of these things influence them? That’s what I want to give them when I make their portrait.” —Megan Snook

“Weather and difficult conditions don’t bother me at all. They simply add to the challenge, and overcoming the challenges is a large part of the enjoyment. Weather, equipment, and time are all part of the fun.” —Jeff Danielson

Matt Brookshire

“In Indiana, what’s beautiful about it is subtle,” said Matt Brookshire. “What is it that makes me want to get out of my truck and run into a field? Indiana has this compelling thing that I want to try to capture. … Indiana needs a champion.”

At 54, Brookshire is honing his craft in search of “sunsets, sunrises, golden hours, and fog” near his Unionville home. He now makes Lake Lemon his primary focus and snaps a lot in Brown County, the Morgan-Monroe State Forest, the Deam Wilderness Area, Lanam Ridge, and the town of Beanblossom.

For his 16th birthday, his father gave him a Minolta 35mm camera. He took his first photos with that Minolta at his uncle’s cabin on Greasy Creek Road in Brown County. He recalls his dad saying, “Most of your best pictures are taken very close to your home.”

Another favorite site was “the Arketex abandoned factory down our street in Brazil [Indiana],” Brookshire said. “It was a photographer’s dream to me. Everything looked like album covers.”

Record-album covers influenced Brookshire heavily. In them he found photographers “working to make interesting pictures that would go with the songs. And as a kid, I’d stare at each one for an hour — however long the album was — and I think I was training my eye.”

He was raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, and Brazil, Indiana, where his family had lots of artwork on the walls and a big book of album covers designed by Hipgnosis, a photography and design collective based in London.

Griffy Walk, “The boardwalk that surrounds Griffy Lake in the fall with a little bit of fog on the water.” | Photo by Matt Brookshire

Brookshire attended photography classes at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, where he learned darkroom processing. But still, most of his photos were developed remotely and commercially. He soon learned how frustrating it was to work with film that you had to take to the local pharmacy to be sent off to be developed, wait two weeks to get back the pictures, and find that only 15 percent were any good. Since digital photography allows him to see instantly and adjust settings as he goes, he sees possibilities for photos around every turn.

“I’ve learned that I will take 600 or 700 pictures of one thing,” Brookshire said, “and in the end, most often, the first or second shot is the best.” He added, “I’m getting better at being prepared.”

Brookshire now uses two Nikon cameras — a D3200 and a D810. “The D810 feels like a tank,” he said. “Quite a step up in size and weight. Even when it snaps a shot, it sounds deeper.” He alternates between standard and telephoto lenses. All of his gear was gifted to him.

He uses Photoshop and different editing tools, including phone apps. He adjusts lighting fairly often, if managing light during the shoot didn’t produce the desired effect. “I really enjoy cropping the most,” he said. “Getting things centered and closer really brings out the composition I see.” He also sometimes uses editing tools to “create wild-looking images, adding things, or using double exposure.”

One thing he finds challenging is “the constant need to store, save, and sort images,” transferring shots to hard drives and cataloging them in folders.

Brookshire is known to many as a talented bass player. He frequents blues jams at the Port Hole Inn and has played with Atom Heart Mother, Lexi Len and the Strangers, the Below Zero Blues Band, and others. He said, “A lot of people have seen me onstage as a bass player and have now started to see me becoming a photographer. It’s fun to have people in the community who know me as both.”

After showing his work at the gallery in the John Waldron Arts Center in 2015, Brookshire provided photos to be displayed at Lennie’s, the former Talkers Tap Room, and elsewhere. He put out calendars of his own work the last three years. Next he dreams of publishing a book of photography.

For his day job, Brookshire works at Big Woods Pizza in Nashville. His long career started with factory work in electronic manufacturing — a helpful background for collecting lots of guitars and music gear. In 2023, he had been working in the mental health field for eight years and was ready for a “reset” that allowed him to have more time for photography, so he landed happily at Big Woods.

How has Brookshire evolved over the years as a photographer? “I’m less driven by what the customer wants and more what I want to see,” he said. “I tend to like the darker stuff — dock-in-fog shot, scary Stephen King novel, Black Sabbath album cover stuff.”

Matt Brookshire Gallery

Click thumbnails for enlarged photos | Captions by the photographer

- Crows in the cornfield — I had been looking for more side roads that would possibly have a group of crows flocking. There was just a bit of fog to add to the mood. The sound they were making made me pause as not to get too close. The fall colors and recently plowed field gave me what I was looking for.

- Sunrise on Lake Lemon, Monroe County, Indiana — The air was thick with smoke from forest fires. When the sun was cresting the horizon, the edges were so sharply defined. The scene was so dynamic and mysterious. I set my tripod up to get the clearest shot I could.

- Lake Lemon — I went to the lake looking for the perfect scary fog picture. There was so much that brought that feeling like seeing the cover of a mystery novel. Once I got out of my car and turned around, the dock stood out the most. I didn’t see the depth of the faces until later.

- Tunnel Road tunnel — The tunnel this morning was perfect. It is very close to my home and I can walk to it. The fog was thick and I had a feeling it would bring about what I could see in my mind as the shot I wanted. I thought that it would enhance the feeling by giving it a black and white filter.

- Fall scape — This was taken in Brown County at a friend’s pond. I ran the picture through a paint app then flipped it. My friend’s pond is off Bear Creek Road. The reflection in the pond under the shade of the trees is peaceful.

- Calf in snow — I looked out my window and could see that the snow was going down thick. I grabbed my camera and made my way to the farm in my neighborhood. The calf in the field was staring at me as if they weren’t happy about it. There were other cows close by but I cropped it to enhance the feeling. I was happy a small amount of their breath came out in the shot.

- The half moon — I took this in my backyard. I like shooting the moon anytime, not just the full moon. I had been getting better at learning to set the timer to eliminate shake to get maximum detail on the surface. Tunnel Road, Unionville, Indiana

- Mt. Gilead Cemetery — I have spent hours taking pictures of this beautiful place. The tree, the unique graves, the church, the wall, the tiger lilies, the train, and when the moon is out or there is some fog. How old is that tree?

- Woolery Mill sky — This is a double exposure of circular lantern lights hanging from the ceiling at the Woolery Mill in Bloomington. Adding the sky later. After putting them together, I noticed how the disco ball began to look like an eye.

- Grey barn on Tunnel Road, Unionville, Indiana — I had been waiting for the right morning for this scene. The barn stood out boldly against the thick fog. I wanted to give the feeling that something was around the corner or off out in the field. I imagined how it would have looked in the morning ready for its purpose to the farmer.

- Singing Tree — I had driven by this tree so many times trying to get a better look. I knew one day when the light was right I would stop for a picture. The tree was on a curve so it was difficult to really look at it. It stood out to me and I tried to capture it the way it would me driving by. The tree is on State Road 45 near the entrance to the Trevlac nature preserve.

- The Richardson Farm — Close to my home is this scene. When the elements are right, it’s in view from my front yard. There was so much going on with the weather. It had just stormed and the sun was coming back out.

- Tunnel Road — I was driving up and down the road I live on trying to get a good shot of the morning fog with the sunrise. This tree stood out and the angle was just right to get the rays shining through the limbs. I was happy that even the leaves falling in the shadow came out. I could hear them landing around me.

- Harvest Moon — This was taken from my driveway. It was still dark out when I began shooting. I followed it down through the trees as the color became very ominous in the sky. The sun was just beginning to rise. Tunnel Road, Unionville, Indiana

Megan Snook

The People’s Portraiture is a photography studio that provides each customer with a varnished tintype of their image, as well as a digital scan, but also more than that. “My goal as a tintype photographer,” said proprietor Megan Snook, “is to produce an image that is true to their soul, to their being, that they’ll cherish the rest of their lives.”

A tintype is a photograph made by creating a direct positive image on a thin sheet of metal, coated with lacquer, and used as the support for the photographic emulsion. Tintypists captured images during the Civil War and were skilled portraitists into the 1900s. Now Snook is bringing the fine art form into our present.

Megan Snook with her tintype camera. | Courtesy photo

Snook, 33, is a history buff, an anthropologist, a journalist, and also a purist. “In 1850, they did not have electricity or high-powered strobe lights required to do modern tintyping that other people are doing [today],” she explained. “I solely use natural light, so all of my work is either right next to a window or outside. So my home studio consists of my woods.”

She offers private sessions at her home and also works from her mobile darkroom, a Toyota 4Runner in which she has traveled around the country taking and selling tintypes at festivals and events. She was recently in the desert of New Mexico and the mountains of eastern Kentucky. She harks back to when tintypists traveled around in covered wagons, plying this same trade. “There’s a lot of grit that’s involved,” she said.

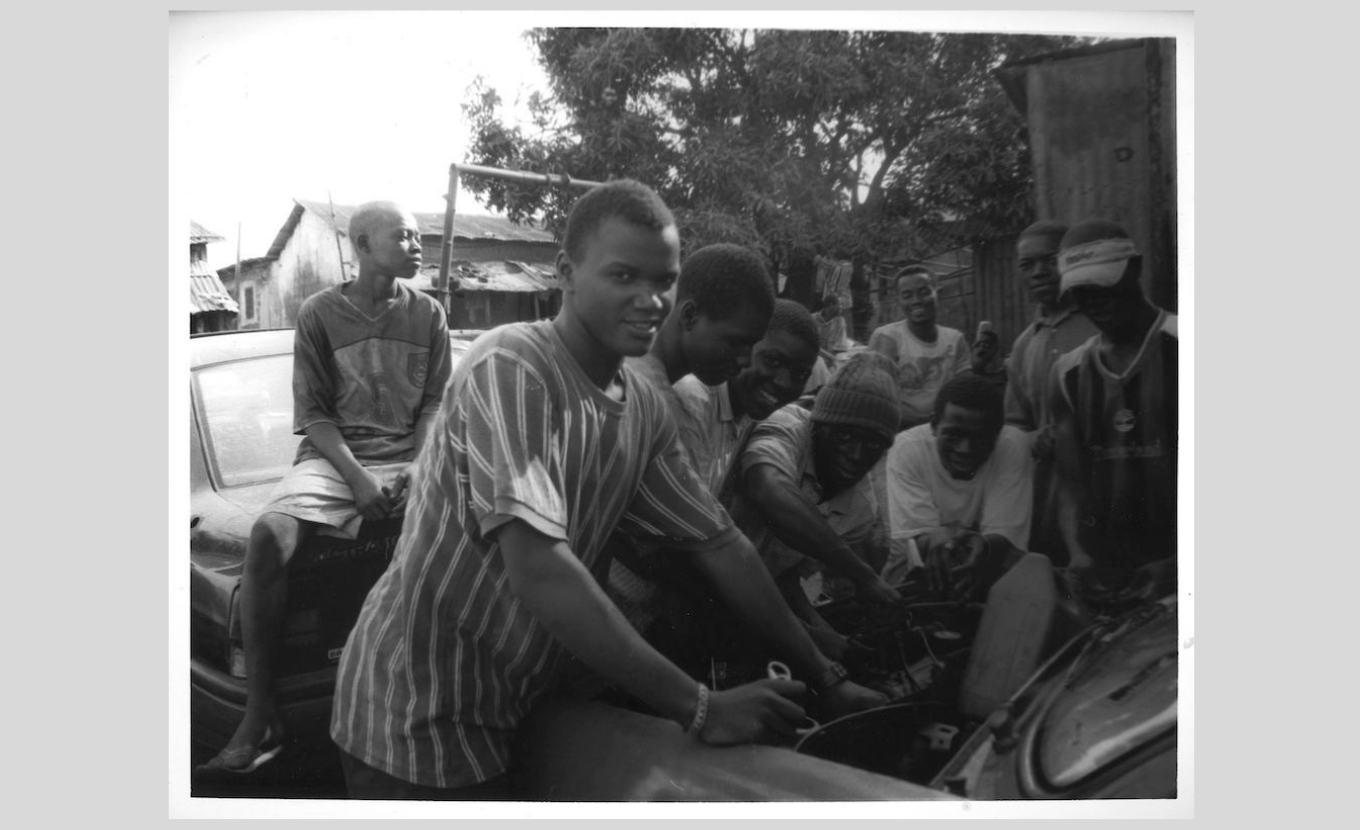

Grit is something Snook has shown in spades. Having parents in the military, she lived many places growing up, including Kansas, California, West Africa, and Bloomington (where she attended Bloomington High School South). She left Bloomington for California, where she did documentary photography, capturing the travels and travails of homeless musicians. She went to Guinea in West Africa and photographed people and places impacted by female genital mutilation. Also in Guinea, she documented how average people made money — mechanics, beauticians, vendors. The political climate was very dangerous. She was present during a military coup d’état in 2008. Throughout all of this, she held a variety of jobs, from teaching social studies and working in the U.S. embassy in Conakry, Guinea, to working at Ben and Jerry’s on Haight Street in San Francisco. She is a self-described Renaissance woman.

Snook started taking photos as a 5-year-old, with a Barbie camera that came with one of the dolls. Later, she used a Leica M4 Rangefinder 35mm, as well as an old Pentax, which was gifted to her and has become her favorite. Her tintype camera is a reproduction made in Vermont in 1983, called Endzone 6. She got it in 2021. It functions and looks exactly as a camera looked in the 19th century.

She got hooked on taking tintypes after taking a long break from photography. Starting in 2009, Snook transitioned from life on the road to more stability. She had a daughter, built a house on a ridge north of Bloomington, planted gardens, and raised chickens. As the pandemic was winding down in 2021, a friend took her to a tintype workshop in Pawpaw, West Virginia. “This is how I reengaged with my craft,” said Snook. “After having two very polarized existences — living in a country where guns are going off and people are getting tortured and then living in the serene woods — tintyping helped me transition back into photography.”

One of the more difficult parts of tintyping is the process of getting — and affording — everything you need. “You have to source all the chemistry and buy specialized equipment that very few people make,” explained Snook. For example, she soaks every plate in silver nitrate in a specialized tank to make the plate sensitive to the light. She sources raw chemicals, such as ether, ammonium bromide, cadmium bromide, potassium iodide, and more, testing different companies’ products and finally finding the ones that produce the results she wants. She mixes them in her home darkroom — a slow and dangerous task, considering the high toxicity levels.

“A limitation,” Snook said, “is that you’ve got only one shot.” Preparing the tintype for exposure can take ten minutes, then something can go wrong with the chemicals. Or the person can move during the exposure, which might take one to fifteen seconds, depending on the amount of light present. “It’s difficult getting people to sit still,” she said. “There are so many variables — the humidity, the temperature, the dust, the wind. Everything kind of adds its little magic to it. Nothing is ever going to be the same.”

She started The People’s Portraiture in January 2023. The name comes from the average, working people in the 19th century who couldn’t afford to have their portraits painted or taken with a daguerreotype camera, an elite precursor to the tintype camera. Tintypes became the common folks’ portraiture, producing the kind of object a spouse puts on the fireplace mantel after a partner passes — which is exactly what Snook hopes happens with hers. She wants each portrait “to be an incredibly cherished object for them that really speaks to who they are.”

Snook described her earlier life as running, moving all the time, and being bombarded by intense situations. Tintyping, in contrast, is about being still and calm, she said. “This process has really helped me be very meticulous and calm and patient and slow down. I love that it’s a slow process and it’s complicated, but it makes you stop and do each step. That’s like a metaphor for my life.”

Megan Snook Gallery

Captions by the photographer

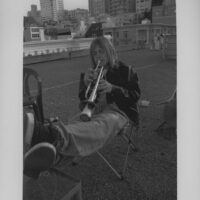

- Jazzman James, San Francisco, California, 2008, Gelatin Silver Print.

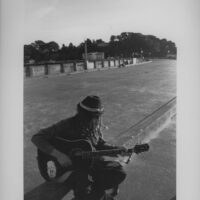

- Stinky Pete Irving, San Francisco, California, 2008, Gelatin Silver Print.

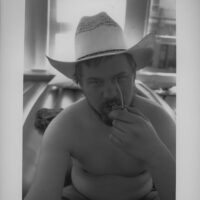

- Cowboy Zack, San Francisco, California, 2008, Gelatin Silver Print.

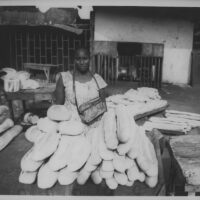

- La Porteuse de Pain (The Bread Peddler), Conakry, Guinea, 2008, Gelatin Silver Print. Woman sells bread to make a living on the streets of Conakry.

- Guinee Games, Conakry, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. Man sells lottery tickets out of a corrugated tin shack.

- Le Mécanicien Automobile (The Mechanics), Conakry, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. Young men learn the art of being a mechanic in a small trade school.

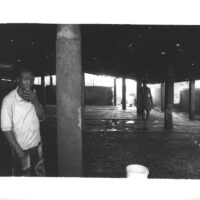

- l’Abattoir, (Slaughterhouse), Conakry, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. Men clean up after a day’s work.

- Cornes de Vache (Cow Horns), Conakry, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. The unused parts of cattle are sorted into piles by the river, where they will remain.

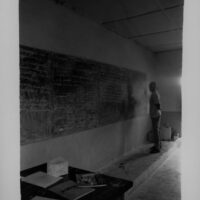

- Le Professeur, Kankan, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. A man teaches young children in a small schoolhouse.

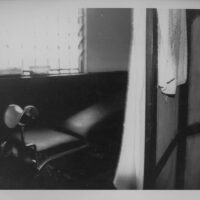

- La Table d’Opération (The Operation Table), N’Zerekore, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. An operation table used to repair fistulas. A fistula is a complication that results from Female Genital Mutilation, known in Guinea as L’excision.

- Les Fantômes de N’Zao (The Ghosts of N’Zao), N’Zao, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. Young boy stands outside of Hope Medical Clinic.

- Les Femmes qui ont Récupéré (Women in Recovery), N’Zerekore, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. Women celebrate their recovery after suffering fistulas due to Female Genital Mutilation. Women are often ousted from their village when they become ill after FGM, as their family believes them to be cursed. These women found their way to a fistula clinic which teaches women a trade as a means to make a living, as their family will rarely accept them back.

- Infirmière de L’excision (Nurse of Excision), N’Zerekore, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. Nurses who operate a fistula clinic.

- École de Beauté (Beauty School), Conakry, Guinea, 2009, Gelatin Silver Print. A young woman learns cosmetology at small beauty school.

- Self Portrait, Bloomington, Indiana, 2023.

Jeff Danielson

“I always firmly disagreed with accepted logic in many areas, and photography is no different,” said Jeff Danielson. “Figuring things out for oneself should be a huge part of the pleasure of photography.”

Never one to like sitting still, at 74 years old Danielson hikes, plays soccer, and rows long distances in his faithful kayak, Stumpy, from which he photographs regularly. He has amassed an enormous portfolio of photos of birds and nature. He has given talks for the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, which has used his photos, as well as for the Bloomington Photography Club.

Danielson’s favorite locations to shoot include Yellowwood State Forest, Brown County State Park, Lake Monroe, Goose Pond Fish & Wildlife Area, Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge, and Brownstown in Jackson County — where he has seen the biggest flock of sandhill cranes anywhere. Twenty years ago, he could have Yellowwood all to himself on weekdays, he said. “Now, like everyplace else, it’s getting crowded any old time.” Danielson travels to impressive places, like Cataract Falls in Owen County, saying, “My whole schtick has always been to show people what they have in their surroundings — things they are often unaware of.”

Stillwater Marsh, “Only possible at first light, as it started to beat through the mist.” | Photo by Jeff Danielson

He eased into photography over many years and then accelerated rapidly when digital arrived. At 9 years old, he prided himself on being able to guess the correct speed and aperture settings on his dad’s camera. He was raised in both the U.S. (St. Paul, Minnesota, and Philadelphia) and Great Britain (Wales, England, and Scotland). Danielson got degrees in art history and ancient Greek from Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, and he was working on a doctorate in classical archaeology at Indiana University when he defied accepted logic, quit, and started the local restaurant the Runcible Spoon on East 6th Street, near the IU campus.

Danielson owned “the Spoon” from 1976 to 2001. There, he photographed lots of candids of people, sometimes resorting to trickery like holding the camera at his waist and guessing the angle. He thought “sticking a camera in someone’s face was a poor way to see the real ‘them.’”

In his teens, Danielson used a Canon half-frame camera (which creates two images for each frame of film), and after college he got a Canon AE-1 with a 300mm lens. Later, he got his first Olympus digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) camera to facilitate zooming in on his son playing college soccer in Minnesota. Then, while hiking and watching birds from his home, he discovered the lens’ utility at capturing birds.

This led to his first one-man show at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater, in 2005. That show was all birds, but he quickly added any form of nature to his repertoire. Since then, he has had one-man shows in Carmel, Indiana, at By Hand Gallery in Bloomington, and at the Spears Gallery and Ferrer Gallery in Nashville, Indiana.

Before he went digital, Danielson usually photographed people and places. And he considered expenses for film and developing carefully. He did not use a darkroom to develop his own shots, mostly because he was concerned about effects of the chemicals. After he went digital, he could make limitless attempts to get a good shot. “Failure no longer cost a fortune,” he said.

Danielson stuck with Olympus equipment over the years, finding it lighter than Nikons and Canons — “important when sitting in a kayak, pointing a camera at a bird up in a tree for forty minutes waiting for it to take off,” he said. Now he uses an Olympus OM-D E-M1 Mark II and carries a second Olympus E-M1. His current bird lens is Olympus’s fixed f/4 600mm. Always carrying two cameras is essential to Danielson’s success, being ready for anything, he said.

Burst mode, also called continuous shooting mode or sports mode, when several photos are captured in quick succession, “is really excellent for critters,” said Danielson, “particularly when they’re moving quickly. The number of great shots I get now is vastly greater thanks to burst and a very good and flexible autofocus system.”

Danielson loves editing his photos, saying, “I’ve experimented with high dynamic range photography and found it unsatisfying. I’ve got editing methods of my own that recreate the scene more to my liking.” Those include a combination of Photoshop CS6 and Olympus and other AI. He said, “Particularly with nature photography, there are many variables … that go into ‘creating’ what I thought I actually saw. Just yesterday I stumbled on and reworked a shot I’d always loved from 2007. … The software back then — and/or my abilities with it — precluded getting it to look anything like what I saw and loved at the time. Now it’s working.”

“I don’t like to learn from anyone else,” said Danielson, “so I try to avoid giving too much advice to others as well, but one thing I have told people is to never throw anything away. They may see it differently in fifteen years, or they may simply be able to do something with it in fifteen years that makes it what they originally intended.”

See more on Danielson’s Facebook page.

Jeff Danielson Gallery

Captions by the photographer

- This is the last known photo of [Bald Eagle] C43. I took it 10/18/2018. She was the oldest bald eagle ever known to be on Monroe Lake, but I didn’t know that when getting the shot, because reading the tag on her leg required a lot of luck and magnification. I followed her for an hour and then sat in my kayak with camera pointed almost straight up (she was at the top a tall tree) for forty minutes waiting for a takeoff shot. Not sure I could have done it with a much heavier camera. And I could have sat in a blind for twenty years without ever seeing her.

- Read the signs and stay on the move. I was about to give up on sandhill cranes that day at Brownstown, but I saw three flying away and figured I may as well see where they were headed. This is what I found after a ten-minute drive — the Medora round barn with hundreds of sandhills landing around it. This happened one day only. They never returned there, and the barn is now demolished.

- TAKE THE SHOT. I hiked past this spot on Yellowwood hundreds of times after this but never found conditions even remotely similar to this Monet layout. Light, vegetation, and water height never came together in this way again. And I love the shot. If I’d waited for another day….

- I often disagree with the commonly accepted advice circulated by photographers. One such is that it’s a waste of time going out in the middle of the day. Yes, morning and evening light can be great, but some of my favorite shots were only possible in the middle of the day. This is an example. Salt Creek would have been completely dark if the sun angle was low. As it was, there were bits of bright sunlight surrounded by wonderful dark shadows. From my kayak, I managed to catch this cormorant in the perfect moment that only existed in the middle of the day.

- ALWAYS carry both cameras. Here I was walking the dogs while it was snowing, expecting to use the short lens. Wrong. Monroe Lake shore.

- It’s about the sky in a given setting — not just the sky. Stillwater Marsh.

- You Never Know What You’ll Find, but a forty-minute drive on a dark and snowy day got me my only family group sandhill shot ever. An all-time favorite of mine, which would have been quite ordinary on a day with great light.

- Again, both cameras. I was looking for fall color (short lens) at Yellowwood State Forest, when this guy swam by. The only time I’ve seen a swimming deer there.

- “Weather and difficult conditions don’t bother me at all. They simply add to the challenge, and overcoming the challenges is a large part of the enjoyment. Weather, equipment, and time are all part of the fun.”

- “I have trouble sitting still, so while I recognize the (occasional) value of sitting in a blind, I do it as little as possible. My hiking taught me that you really do never know what’s around the next corner, and surprisingly often it’s something really cool that I never would have seen sitting in a blind.”

- “With landscapes, I take varying versions one shot at a time. Quite often what becomes an important variable only becomes obvious later on the computer screen. And in a rapidly changing light situation in particular, multiple shots are a necessity.”

- Dramatic light at midday. Emerging from deep shade into full sunlight.

- The sandhills were settling for the night. I had to figure which of their spots would give me the silhouettes I wanted. Brownstown.

- Sometimes it’s the small things, like turkey tails in January. And again — I had both cameras while walking the dogs in our valley behind the house.

- “This one is the iconic (maybe) choice as an example of the usefulness of burst. Catching the wing-tip in the water can take many more years without it.”

Find more photography and photographers in Limestone Post’s photography archives.

![This is the last known photo of [Bald Eagle] C43. I took it 10/18/2018. She was the oldest bald eagle ever known to be on Monroe Lake, but I didn’t know that when getting the shot, because reading the tag on her leg required a lot of luck and magnification. I followed her for an hour and then sat in my kayak with camera pointed almost straight up (she was at the top a tall tree) for forty minutes waiting for a takeoff shot. Not sure I could have done it with a much heavier camera. And I could have sat in a blind for twenty years without ever seeing her.](https://limestonepostmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Danielson-A2-copy-200x200.jpg)