‘For me, the journey we’re about to embark on has been written on a map of dreams.’

—Wade Davis, anthropologist, ethnobotanist, former National Geographic Explorer in Residence

Aside from harboring soggy, wetland environments and providing refuge to rare and endangered plant and animal life crucial to their regions’ biodiversity, Monroe County’s Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve and Colombia’s Amacayacú National Park aren’t easily connected dots.

The two protected natural areas occupy latitudinally disparate landscapes three thousand miles apart. Beanblossom lies north of Ellettsville — in the temperate Midwestern United States. Amacayacú lies north of the Amazon River — west of the tropical Colombian city of Leticia, three hundred miles south of the equator, where Peru, Brazil, and Colombia meet in the world’s greatest jungle.

Beanblossom is 733 acres; Amacayacú is 1,629 square miles.

The connection is personal. Both preserves have occupied crucial coordinates along a half-century trail that I’ve blazed between them in my life as an environmental/nature photographer and writer.

In June, I will directly connect the two, when I pack up my gear after this Limestone Post photo study at Beanblossom and carry it on an expedition to Amacayacú in the Colombian Amazon for a memoir I’m working on called A Photographer’s Fifty-year Journey to the Amazon River.

To get my hiking legs back and re-hone my photo rhythms after a winter preoccupied with storylines and syntax, I spent six weeks hiking and photographing Beanblossom Bottoms, which has been identified as an ecologically unique and important wetland habitat by the Society of Wetland Scientists.

A half century of Amazon dreaming

The Amazon dot dates back fifty years to the mid-70s, when I traveled through Colombia on six surreal adventures buying and exporting handicrafts.

The author’s first contact with the Colombian rainforest was his purchase of 160 Amazon Indian baskets in 1976 in Bogotá. His plans at the time to visit the jungle region never materialized due to U.S. and Colombian authorities’ interests in his activities.

Steven C Imports’ signature products were handmade cotton wall hangings from the arts village of San Jacinto, which sits some 50 miles south of the Caribbean resort of Cartagena. Along the way, my partner, Hilario Martinez, and I discovered leather bags from the Andean foothill city of Bucaramanga.

My first and best Bloomington customers were Donna and Roger Hawley at the Rama House in the middle of the freshly built Dunkirk Square, and Larry and Hilde McConnaughy of Irish Lion fame, who owned a gift shop called Fields of Aiku where Siam House is today.

In 1976, the year after the Amacayacú National Park was established, I ordered 160 Amazon Indian baskets in Bogotá and made plans to fly to Leticia on my next trip. Mostly because of American and Colombian government interest in my activities, I shuttered the importing business in 1977.

I never made it to Leticia. I never photographed the Amazon.

Announcing Beanblossom Bottoms

The Beanblossom Bottoms dot dates to the Sycamore Land Trust’s formation in 1990, when I started cutting my journalistic wetlands chops as a staff writer at The Herald-Times.

I’ve long told folks that I wasn’t there when Sycamore was born. But I was the first person the parents called after the blessed event.

Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve, April 2024—Tom Zeller, a founding member of Sycamore Land Trust, was instrumental in establishing the Beanblossom Bottoms preserve. The advantage of land trusts, he said during a hike through three feet of water in April, is that their properties are protected forever.

The land trust was spawned at a 1990 meeting called by Tom Zeller, who was a board member of the Sassafras Audubon Society, which at the time was an activist group on the cutting edge of environmental protection.

After Sycamore was formed, Zeller called me at the H-T, and on February 16, 1991, I wrote a story announcing the land trust’s creation, under the headline “Group to guard green space.” The mission was clear and simple, founding Sycamore board member Lucille Bertuccio told me.

“The location and topography of Monroe County is something we all love and want to keep,” she said.

A year later I wrote a story headlined “Donation returns farmland to nature” about landowner Barbara Restle’s 80-acre contribution to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service along the Beanblossom Creek, which today is surrounded by the Sycamore nature preserve.

Gazing at her former farm field 32 years ago, Restle told me her mission was likewise clear and simple: “This belongs to Mother Nature.”

Returning to Colombia for Amazon exploring

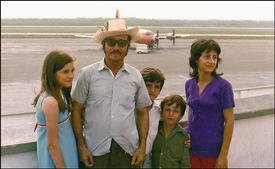

Barranquilla, Colombia, May 1974—The author’s journey to the world’s greatest river began in the mid-1970s, when he operated an importing business called Steven C. Imports with his Colombian partner Hilario Martinez. Surrounding him in this photo are four Martinez children (clockwise from the left): Estella, Patricia, Reinaldo, and Ricardo. | Courtesy photo

In an age when intercontinental communications were snail mail, I lost touch with mi familia Colombiana — Hilario, his wife Teresa, and their three daughters and three sons.

In the spring of 2023, I received a Facebook friend request from middle Martinez sister Luz, who was 14 the last time I saw her, 48 years ago. In October, I flew to Europe and spent three weeks with Estella, Luz, and younger sister Patricia in Austria and Spain.

While flying home, I decided to return to Colombia to see Teresa and brothers Marcos and Ricardo — and finally photograph the Amazon. As my oldest high school friend Michael asks, “If not now, when?”

On June 14, my family and I will fly to Barranquilla, Colombia, where Luz’s daughter Laura has an apartment in the hotel we will stay in. Luz will be there when we stop over again on our way home.

From there, we will fly to Leticia for a day before ferrying 40 miles upriver to the Amazon’s confluence with the Amacayacú River, from which we will float another two miles upstream to the Tikuna Indian village of San Martín de Amacayacú — population 500.

Barranquilla, Colombia, May 1974—After losing touch with his familia Colombiana for 48 years, Higgs reestablished his relationship with them when Luz Martinez (right) contacted the author on social media in spring 2023. In October last year, Higgs visited her and sister Patricia, who now live in Spain, shown here in 1974 with father Hilario and brothers Reinaldo and Ricardo.

We will stay at the Casa Gregorio, an ecolodge on the tributary, surrounded by the Amacayacú National Park.

Amazon training at Beanblossom Bottoms

Our Amazon adventure will be challenging for a 73-year-old with a backpack full of weighty, professional camera gear, a bad knee, and a couple of spinal issues.

Carrying my camera sling bag in Spain had caused severe discomfort, so I switched to the backpack, figuring that even weight distribution would help. When contemplating where to test this new approach, Beanblossom Bottoms was the only place that came to mind.

Beanblossom isn’t the Amazon. But it is a wetland environment that requires walking and photographing from sometimes slippery and submerged boardwalks.

To prepare for the jungle, I spent six weeks physically, visually, and photographically training at Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve.

Protecting Beanblossom Bottoms ‘forever’

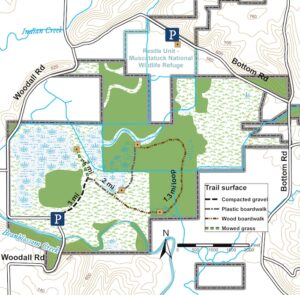

Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve, March 2024—While the Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve is only 733 acres and Colombia’s Amacayacú National Park — which the author will photograph in June — is 1,629 square miles, both are physically and photographically similar wetland environments with boardwalk trails.

Inviting Tom Zeller on a walk-and-talk about Beanblossom Bottoms was a no-brainer. And even though the road, parking lot, and trails were underwater following three days of mid-April, rainforest-like downpours, we slogged through flowing, knee-deep creek water to the benches at the boardwalk trailhead.

Zeller’s connection to my Beanblossom–Amazon trail predates his founding role with Sycamore. In a way, he and our friend John Blair down in Evansville checked the first dot.

I was selling cameras at Hazel’s Camera Center on Kirkwood Avenue in 1978, when Zeller walked in the door, a smile on his face, a stack of newspapers under his arm. He asked if he could leave a pile of the Ohio Valley Environment on our counter. OVE was a newspaper focused on the region’s environment, published by him and Blair, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer.

In fact, their activist style of environmental journalism has been the template for four books and thousands of newspaper, magazine, and online articles and columns I’ve written on the environment since my 1986 final masters project at the IU School of Journalism: Clearcutting the Hoosier National Forest: Professional Forestry or Panacea?”

***

As an inch of water unfalteringly curled around our boots on the typically above-water platform and bench, Zeller explained that Restle, a former Sassafras Audubon board president, initially offered her land to Sycamore. But she couldn’t wait for the new nonprofit to get its footing and donated her farm field to the U.S Fish & Wildlife Service as the Restle Unit of the Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge.

“We were two months old and didn’t know anything,” he said.

The land trust newbies were likewise “nervous Nellies” when considering the first piece of the Beanblossom preserve that they purchased. An eager seller gave them two years to raise $50,000 for what is now part of the site’s northwest corner.

“We were wringing our hands,” Zeller said. “Should we sign this contract? … Within six weeks, we had the $50,000.”

***

Zeller said the Beanblossom legacy left by Sassafras and Sycamore visionaries like George Heise, Mary Kay (Moody) Rothert, Lucille Bertuccio, Moira Wedekind, Dave Hudak, Hank Huffman, John Gallman, Ed and Lise Schools, and others will endure for eternity.

Deed restrictions as tools to protect nature eventually expire under Indiana law, he explained. Protections through “third, forever parties” like Sycamore last in perpetuity.

“The beauty of the land trust business is it’s forever,” he said. “… You can start with a soybean field, and in 200 years, it’s going to be a mature oak-hickory forest.”

Speaking more visionally, Zeller said there must be wild places like the Beanblossom Bottoms that are left for nature to evolve and change, places where humans can also seek refuge.

“This is as good a nature walk as you can find in Indiana,” he said. “It’s stunning.”

Encompassing ‘incredible diversity’

Dead and decaying trees at Beanblossom Bottoms provide critical habitat for a variety of birds and other wildlife. Bird species observed during a brief stop at the Robert Anthony Johnson observation deck in May 2024 included red-winged blackbird, pileated woodpecker, and tree swallow.

The Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve’s 733 acres are but a chunk of a larger area of Sycamore-protected wetland ecosystems called the Beanblossom Creek Conservation Area, which protects nearly 1,100 acres in the Beanblossom Creek Watershed in Brown and Monroe Counties.

This wildly meandering waterway drains 92 square miles of Indiana uplands and feeds the White River between Stinesville and Gosport, some 25 miles due west of its headwaters near Spearsville in northeastern Brown County.

Nearly two dozen endangered, protected, special concern, and notable species survive in the Beanblossom environs, among them native orchids, American bittern, American bald eagle, Henslow’s sparrow, Kirtland’s snake, Indiana bat, and cypress firefly.

The National Audubon Society has designated Beanblossom Bottoms a State Important Bird Area; the Society of Wetland Scientists has designated it a Wetland of Distinction.

In a 24-hour Sycamore event called the 2022 BioBlitz, more than 70 researchers observed 900-plus plant and animal species at the Bottoms.

“The limestone bedrock of this area provides for sinkholes and swamps, creating wetlands that support incredible biodiversity,” Sycamore says on its website.

Beanblossom’s significance in the broader picture

Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve, April 2024—During a hike in April, former Monroe County Naturalist Cathy Meyer said Indiana has lost more than 87 percent of its wetlands since the French explorer La Salle reached the state in 1679. Recent anti-wetlands legislation passed by the Indiana General Assembly will further deplete what is left.

I am not a naturalist. So I’ve long relied on experts like retired Monroe County Naturalist Cathy Meyer for definitive answers on matters such as species identification and, say, animal behavior. Indeed, she was a bit of a regular on nature tours I led through my business Natural Bloomington Ecotours & More between 2013 and 2018.

So I invited Meyer for a walk-and-talk over the entire 2.5-mile trail at Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve on a magnificent afternoon a week after my watery wade with Zeller. Our conversation began on the eagle observation deck, discussing the role wetlands like this one play in regional ecosystems and beyond.

“It’s pretty significant,” she explained, “because Indiana, as you know, has lost most of the wetlands that we once had. Eighty-seven percent have been destroyed.”

And with recent reductions in wetland protections by the Indiana General Assembly, she warned, “it’s going to happen at a more rapid pace.”

***

To illustrate Beanblossom’s significance in the broader conservation “puzzle,” Meyer said the primary water pollutant in Indiana is siltation in runoff from agriculture fields, construction sites, and other surface water sources.

“Every time we get a heavy rain, all that mud and silt is running into the water, and carrying with it nutrients like phosphates and nitrates that promote algae growth,” she said.

Wetlands in the Beanblossom Creek natural complex hold and absorb siltation that otherwise would flow west into the White River, thus improving water quality there — and downstream.

“In the bigger picture, that goes into the Wabash River, and that goes into the Ohio and down the Mississippi,” she said.

Eventually White River pollution reaches the Gulf of Mexico’s Dead Zone, an area roughly the size of six Monroe Counties — or the entire state of Delaware — where nutrients “trigger algae blooms that choke off oxygen in water and make it difficult, if not impossible, for marine life to survive,” The Nature Conservancy says.

“The Midwest is where all that fertilizer and sediment is coming from that’s causing that lack of oxygen in the Gulf of Mexico,” Meyer said.

And Beanblossom Bottoms is but one little piece of that continental pollution puzzle.

“If these tributaries can be cleaned up, it will have impacts farther downstream,” she said.

***

Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve, April 2024—Mayapples are among the 236 species of flora identified by the Consortium of Midwest Herbaria at Beanblossom Bottoms.

In addition to water storage, Beanblossom Bottoms provides critical support to wildlife species that exist only in wetland habitats, Meyer said. Among the endangered, threatened, and unique species there is an insect called the cypress firefly, which is known for its “unique flashing pattern.”

So named because of its affinity for swamps that support cypress trees, this species of beetle had previously been found in Indiana only at the Twin Swamps Nature Preserve, where the Wabash meets the Ohio River, in cypress swamp territory.

Cypress trees do not grow at Beanblossom Bottoms. Sycamore Land Trust, along with a researcher from Indianapolis Zoo, just received a grant to study the cypress firefly’s unusual presence outside a true cypress swamp.

Species like the red-headed woodpecker we saw at the Robert Anthony Johnson observation deck love the dead, standing trees that could not survive the deepening water levels, Meyer said. So do the pileated woodpecker and tree swallow we watched.

“It’s nesting habitat for bald eagles,” she said.

***

Echoing Zeller, Meyer said wetlands likewise offer solitude and recreation to humans who need it.

“People come to wetlands to hunt, fish, and, when there’s enough water, for kayaking,” she said.

None of those activities are allowed at Beanblossom, but pointing to her binoculars and my Nikon, Meyer said hiking, birding, and photography are popular there.

So is plant study, she added, citing two “really interesting plants” as examples — the cardinal flower and the purple fringeless orchid.

“There are a lot of plant enthusiasts who come out and look for those,” she said.

Amacayucú National Park: Connecting the final dot

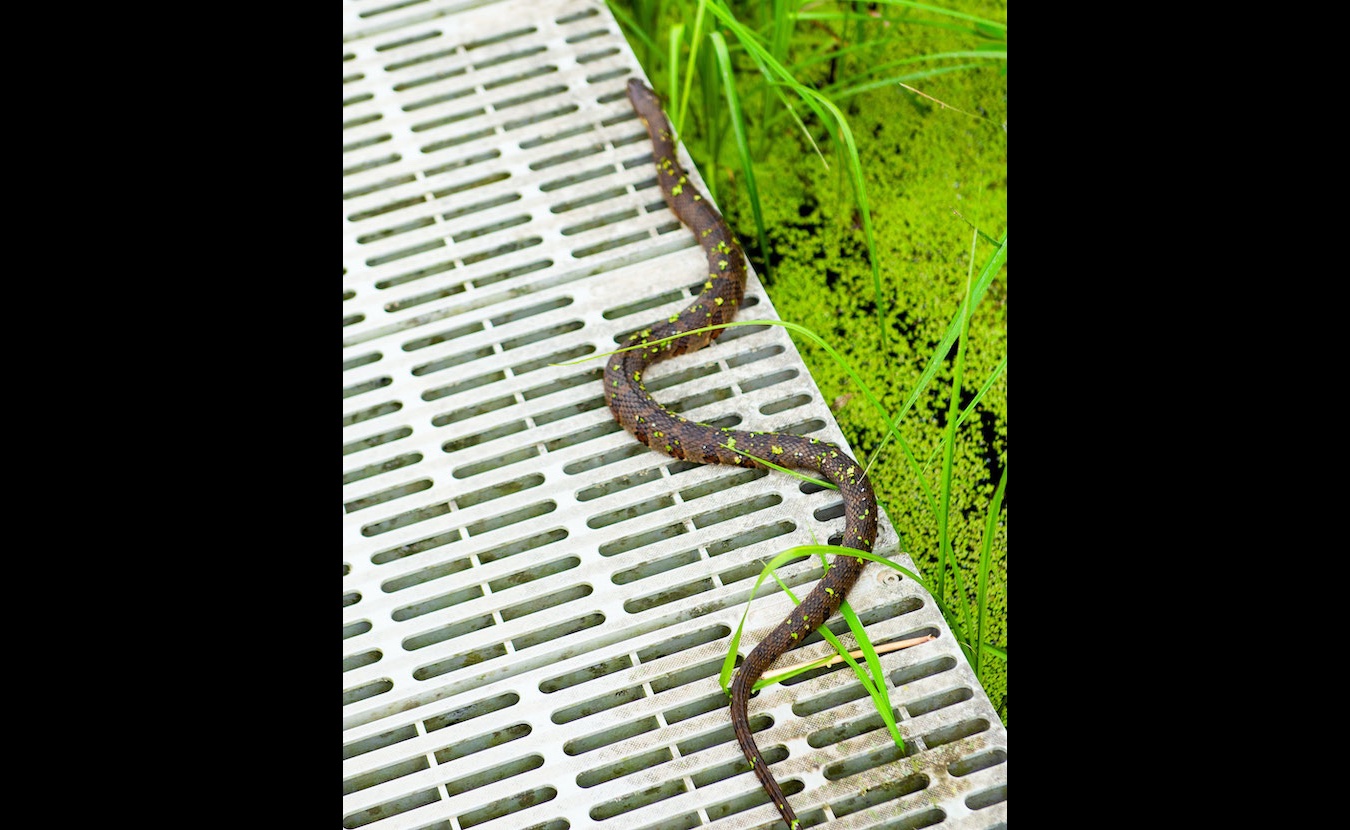

Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve, June 2015—Beanblossom Bottoms is not home to Amazonian giant river turtles, but it is to painted turtles and other reptiles, including the state endangered Kirtland’s snake.

A continent away from Beanblossom Bottoms, the Amazon River’s Amacayacú National Park awaits the final dot check.

Colombia’s first dedicated nature preserve, Amacayacú represents less than 1 percent of the country’s 270,000 square miles of Amazon Rainforest.

From Leticia, unbroken jungle extends six hundred miles north-northeast to the Venezuelan border and four hundred miles northwest to the Ecuadorian border. For perspective, Bloomington is six hundred miles from the U.S.–Canadian border at Lake Superior and four hundred miles from Kansas City.

Amacayacú National Park supports almost half the country’s mammals and more than a third of its bird species. It’s home to more than five thousand plant species and hosts the largest diversity of primates in the world.

The Gems Travel website calls Amacayacú an “ecotourism paradise.”

***

Eco-paradise, for sure. San Martín has no vehicles or roads.

But we’re spending only three days in the deep jungle because, well, the heat, humidity, and bugs will be intense. And we’re taking 11- and 19-year-olds to a place with no Wi-Fi.

From the ecolodge, we’ll travel with an English-speaking guide on community and nighttime jungle walks over Beanblossom-like boardwalks and take boat trips to the Maikuchiga Monkey Sanctuary and to Tarapoto Lake in search of the Amazon’s world-famous pink dolphins.

During our two days in Leticia, we’ll stay in a hotel — with pool and Wi-Fi — and explore small slices of the adjoining border areas in Peru and Brazil.

Granddaughter Raina and I may stay longer, maybe take a boat to Iquitos.

Or I may just return home to my local eco-paradise, Beanblossom Bottoms.

Beanblossom Bottoms Nature Preserve, March 2014—Raised, wooden boardwalks over water, like this one at Beanblossom Bottoms, are common in the Colombian Amazon. The author re-honed his wetland photography techniques at Beanblossom for his trip to the jungle in June.

Read More about Indiana’s Wetlands

What’s at Stake in the Debate Over Indiana’s Wetlands?” Article and photography by Anne Kibbler, which is part of the award-winning series “Deep Dive: WFHB & Limestone Post Investigate.”

And read more Higgs

“On Saving the Deam Wilderness and Hoosier National Forest” | Photo essay by Steven Higgs

“New Legislation Would Double Size of Deam Wilderness,” by Steven Higgs