What do babies know? For most of modern history, the expert consensus was: not much. Most scholars of child development would have agreed with philosopher and psychologist William James, who wrote in the late 19th century that for babies, the world is “one great blooming, buzzing confusion.”

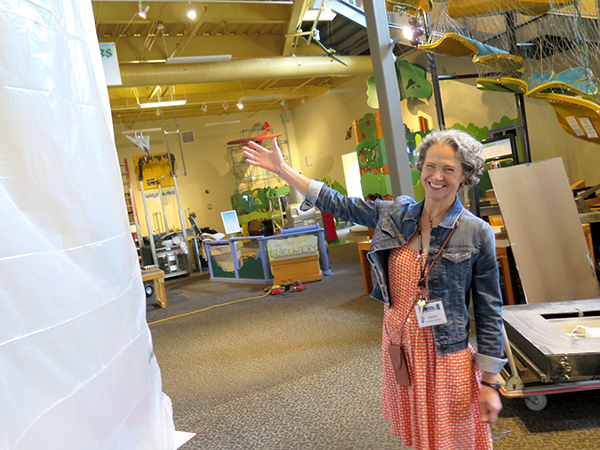

Local scientists have teamed up with the staff at WonderLab to create exhibits and activities tailor-made for the museum’s youngest patrons. Executive Director Karen Jepson-Innes shows some of the construction of the coming Science Sprouts Place. | Limestone Post

But that view underwent a major shift a few decades ago, when psychologists started taking a greater interest in infant development and, through cleverly designed experiments, discovered that very young children were capable of much more than was previously thought. Some of these pioneers in infant development research happen to be right here in Bloomington, in the Department of Brain and Psychological Sciences at Indiana University.

Now, directors at WonderLab, Bloomington’s award-winning children’s science museum, are taking advantage of the local expertise on early development to design “Science Sprouts Place,” a section of the museum tailor-made for its youngest patrons, from zero to three years old. “We don’t just want people to learn science,” says Emmy Brockman, WonderLab’s education director, “we want science to inform everything we do.”

IU psychology’s Linda Smith (top) and Emily Fyfe work in infant development. | Courtesy photos

The science of infant learning

In the late ’70s, Linda Smith joined the psychology faculty at IU and quickly set to work transforming our understanding of how infants think and learn. Some of her biggest contributions have been in the field of language development, where her work has shown how it is that children learn words so easily. For example, she and her collaborators found that children as young as two years old have a “shape bias” — when they hear an object labeled with a new word, they generalize that word to other objects of the same shape. This is a great strategy for learning early words, many of which refer to discrete objects.

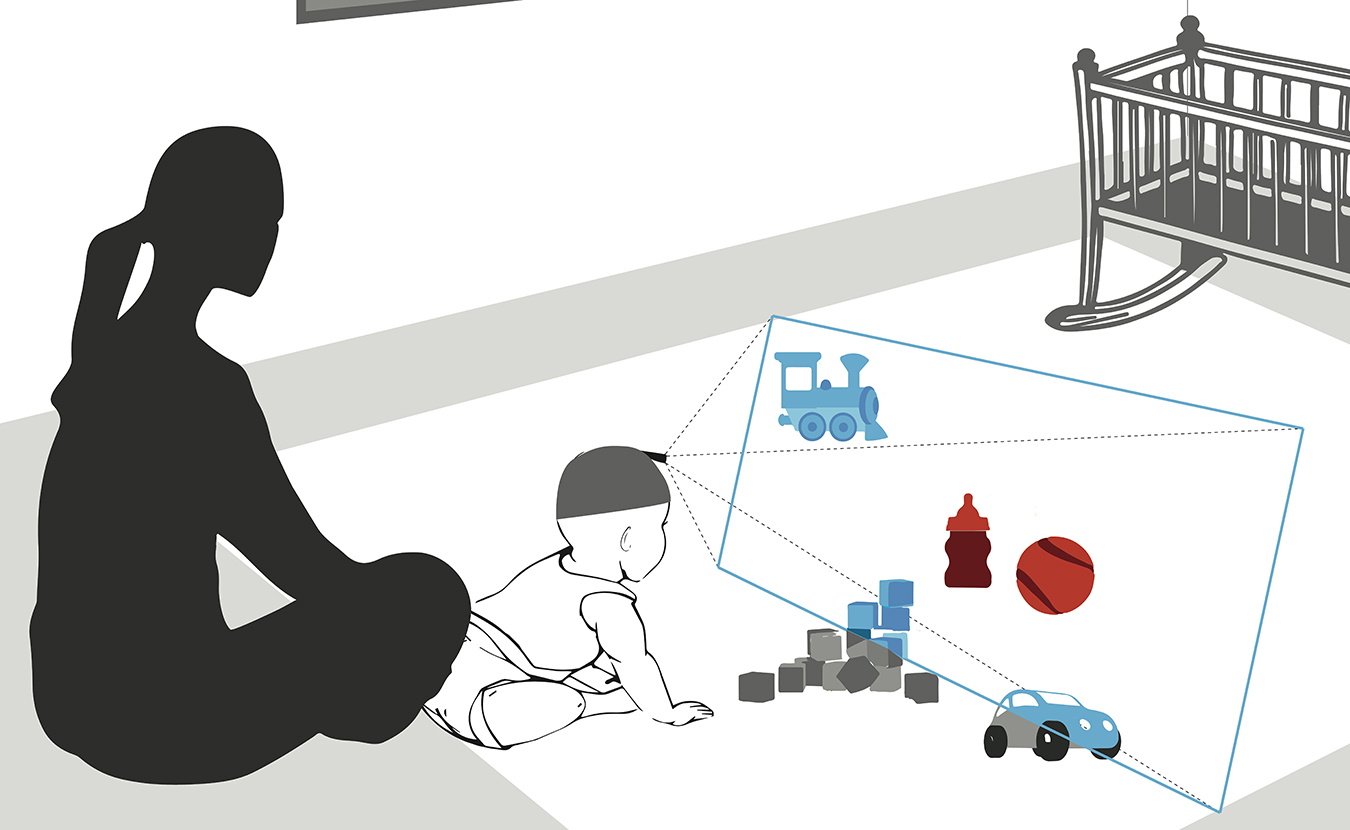

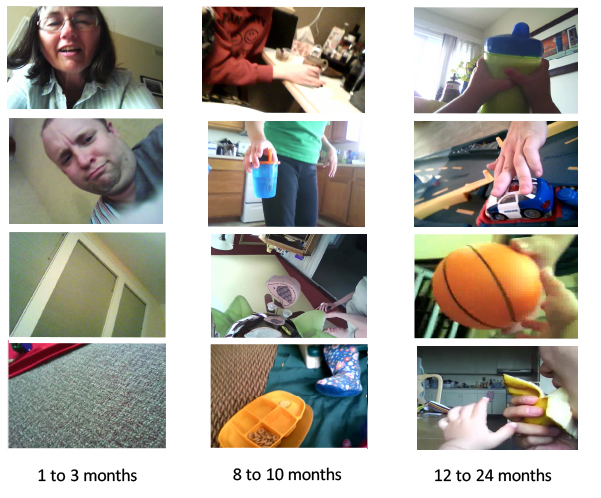

Over the course of her career, Smith has worked to provide an even more detailed picture of how infants learn. In the past few years, she and collaborators at IU and elsewhere have been conducting studies in which infants wear head-mounted cameras, offering a “baby’s-eye view” of the world. Turns out, infants see things very differently from adults — their view is often dominated by a single object, whereas adults tend to have multiple objects in view. This way of seeing the world facilitates learning, Smith believes, explaining why, for example, studies have found that babies are so skilled at learning faces. “One experience with you, and they’ve got you,” she says.

Emily Fyfe, a more recent addition to the IU psychology faculty, studies how children think about and solve math problems. Although her work focuses on kids ages four and up, it draws heavily on findings from younger children. “There’s tons of research showing very young kids know a lot about math concepts,” she says. She gives the example of the well-documented finding that infants as young as nine months can do a kind of basic arithmetic: If they see a single object, followed by a screen going up and a hand adding a second identical object behind the screen, they expect two objects to be there when the screen comes down. If they see only one object, they’re surprised. (Babies show surprise by looking longer at an unexpected event than at an expected one.)

Infants’ prodigious learning capacity has led Smith to make the bold pronouncement that “babies are on the cutting edge of artificial intelligence.” Designers of artificial intelligence (AI) devices — from digital personal assistants like Siri to smart cars to fraud-detection apps — have a lot to learn from babies, she argues.

The new WonderLab exhibits will use research done by IU scientists, such as Smith’s study of infant line of sight. | Images courtesy of Linda Smith

“[These devices] are given a massive amount of data,” she explains, “but if anything novel happens, they don’t know what to do.” Babies, in contrast, “are not trained on everything”; other than caregivers occasionally pointing out something interesting, they receive very little instruction about the world, she says. What’s more, the information infants get is “very local,” Smith says. Take the category of cups. Babies mostly see their own sippy cup, maybe their caregiver’s coffee cup, and one or two others. And yet, with this limited amount of data, she says, they easily learn the concept of “cup,” even applying the word to instances they’ve never seen before. “It’s a smarter, more flexible, more innovative system [than AI],” Smith says.

From the psych lab to the science museum

All the accumulated wisdom about early development has been indispensable to directors at WonderLab, who are working to create a space in the museum specifically for children zero to three. As Brockman explains, the decision to focus on this age group came after she and her colleagues noticed more and more infants and toddlers visiting the museum in the past few years.

To respond to the needs of this group, Brockman started a weekly “Science Sprouts” class a couple of years ago. The class filled up so quickly she added two more — but directors felt it still wasn’t enough. “We realized we need more than a class,” she says. “We need a space. We need something here every time people come that speaks to the unique developmental needs of kids ages zero to three.”

WonderLab is currently working on a space dedicated to children ages zero to three, with new exhibits scheduled to open in the fall of 2019. | Limestone Post

Realizing they had an invaluable resource right in their own backyard, WonderLab directors formed an advisory council of IU child development experts, including Fyfe and Bennett Bertenthal, whose work focuses on infants’ perceptual and motor development. Over the past year, the group met regularly to talk about research on infant cognition and to consider ways of applying it to the museum’s new space.

WonderLab’s Education Director Emmy Brockman says, “We want science to inform everything we do.” | Courtesy photo

They also enlisted the services of Mindsplash, a museum consultation organization, to help with the design process. The plan, Brockman says, is to transform one of the current rooms in the museum into a space dedicated to children three and younger. “It’ll be an immersive environment that’ll have a whole bunch of different kinds of experiences,” including activities related to language, motor skills, and cause-and-effect, says Brockman. The exhibit space, called Science Sprouts Place, is slated to open in the fall of 2019.

Recommendations from IU experts are already being incorporated into fundamental design elements. For example, the space will be separate from the rest of the museum, Brockman says, a decision that Bertenthal endorses: “You don’t want them to be scared off by loud noises and bigger children,” he explains. “You want a quiet, safe environment where parents are close enough that children can check in with them.”

Another point emphasized by IU psychologists, Brockman says, is that infants learn in social contexts. “That’s something we can make happen,” she says. They are considering different ways to promote social interaction, such as by limiting supplies so that children engaged in the same activity are encouraged to share and compromise.

Fyfe’s descriptions of children’s early sequencing abilities have led directors to think about ways they can draw on and encourage these skills. Ideas range from the simple, such as using rugs with checkered patterns rather than solid colors, to the more complex — designing activities that prompt children to create patterns based on multiple dimensions at once, such as shape and color.

IU’s Bennett Bertenthal is one of the scientists on WonderLab’s advisory committee. His work focuses on infants’ perceptual and motor development. | Courtesy photo

Why zero to three matters

IU psychologists say focusing on such young children is important, and not just because they’re a substantial part of the museum’s clientele. The period from birth to three is one of “extreme plasticity,” says Bertenthal, referring to the brain’s ability to be molded by experiences.

Because of this plasticity, Smith says, very young children especially benefit from being in an enriching environment. This has important implications for children who lag behind in their development, she says — whether it’s their ability to learn words, focus their attention, or control their impulses. While genes explain some of the differences in the rate at which kids develop, she acknowledges, the environment does too — and that’s where places like WonderLab can help. Although she did not consult on the Science Sprouts project, she is excited about its possibilities: “If the community comes together and gives these kids similar kinds of experiences, they can help level the playing field.”

Fyfe agrees: “It’s probably the most rewarding thing we can do with the research we conduct.”

Turns out, the answer to the question “What do babies know?” is a whole lot more interesting — and promising — than William James thought.