Several shootings at a local park. A gun found in a student’s bag. A call to 911 about gunfire at a local football game. As a community, Bloomington is not immune from gun violence. In fact, according to Captain Scott Oldham of the Bloomington Police Department (BPD), Bloomington is far from quiet when it comes to gun violence. “Bloomington has turned out to be a place where we have more than our share of violence,” Oldham says. Each incident presents the possibility of a mass shooting in a community where no one wants to believe that it could happen here. Mass shootings are not an urban problem. Some have happened in communities smaller than Bloomington.

So, many in Bloomington are asking what people in similar communities have asked themselves: If it’s no longer a question of “if,” but “when,” how can it be prevented?

Answering this question is difficult without considering how society copes with these traumatic events now. Since the shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado in 1999, the focus on prevention has been from a law-enforcement perspective. Now experts, armed with more information, believe the focus should come from the public-health sphere. But managing gun violence from a public-health sphere means that you must have data and information to guide the path to actual prevention. Data such as how many school counselors or social workers at our local schools serve students? Do police officers or school resource officers on school grounds really prevent guns in book bags?

The basic question now: How prepared are our schools with respect to what experts say is the “Value of Student Support Services versus a Law Enforcement Presence in Schools”?

To understand why we are so behind from a public health perspective, we must understand just how much the efforts have been hampered by a sheer lack of research on gun violence, why gun violence happens, and how it proliferates.

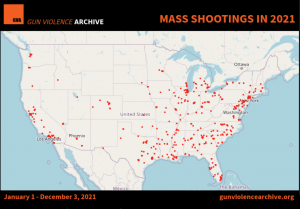

The Gun Violence Archive defines a mass shooting as a minimum of four victims shot, either injured or killed, not including the shooter. The archive says Indiana has experienced 31 mass shootings in the past three years. | Source: Gun Violence Archive

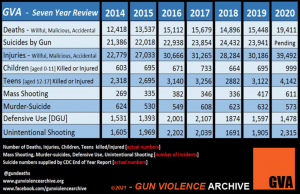

The Gun Violence Archive (GVA), an independent and nonprofit data collection and research group, says that 2021 is our deadliest year in two decades. Some attribute it to the violence inbred in American society. Others conclude that unimpeded access to firearms is the problem. But politics have kept us from a comprehensive understanding of mass shootings. Since the 1996 Dickey Amendment, virtually no research except that funded by private foundations has been done to study the impact of mass shootings and gun violence.

In 1996, U.S. Rep. Jay Dickey (R-AR) and the National Rifle Association’s lobby inserted an amendment into a federal government omnibus spending bill. This amendment barred the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from funding efforts to advocate and promote gun control. The chilling effect was immediate. Federal research funds were heavily restricted, and this ultimately log-jammed any research on gun violence.

When gun violence continued, Dickey had regrets. In 2012 he co-authored a Washington Post op-ed addressing the attempts to suppress comprehensive gun research. “We must learn what we can do to save lives,” he wrote. “It is like the answer to the question, ‘When is the best time to plant a tree?’ The best time to start was twenty years ago; the second-best time is now.”

Since then, federal gun-violence research dollars have increased, with $12.5 million going to both the CDC and the National Institutes of Health, and then a second round of approval in the 2021 fiscal year was granted. For 2022, President Biden has requested an additional $50 million to go to the CDC and NIH for research. For Katherine Schweit, a former FBI agent and author of Stop the Killing: How to End the Mass Shooting Crisis, having these additional research dollars is critical for understanding why gun violence continues.

Katherine Schweit is a former FBI agent and member of a gun-violence task force created by former President Obama and headed by then-Vice President Joe Biden. | Courtesy photo

Schweit was a member of the task force created by President Obama after the 2012 mass shooting at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. Headed by then-Vice President Joe Biden, the task force pursued legislative action, increased gun violence research, and implemented 23 presidential executive measures designed to curb gun violence.

“After Sandy Hook, I got tagged to be on the vice president’s White House team, and the lack of data was a problem,” says Schweit. “I felt that it was incumbent that the FBI do the research.” Now, she says, because of FBI research and that done by organizations such as National Institute of Justice, Everytown for Gun Safety, and Say Something, Do Something, “we have a much better picture of who these shooters are and when they will strike and why.”

Researchers Jill Peterson, Ph.D., and James Densley, Ph.D., echo her sentiments. Authors of The Violence Project: How to Stop a Mass Shooting Epidemic, these two researchers created a database on mass shooters, including more than 150 data points of life history for more than 170 shooters. Researchers, law enforcement, and the media now depend on this data. In creating the database, Peterson and Densely also interviewed multiple mass shooting perpetrators who were still alive, their families, the victims of their crimes, first responders, and research experts. They found data-driven evidence that could lead to real solutions for understanding and addressing the issue of mass shooting.

Preparation and prevention vs. security only

Using data-driven evidence and evidentiary-based solutions, researchers can now examine mass shooting through the prism of a public health approach. “When I think about a public health response, I think about a response that is data-driven,” says Densley. “It is a response rooted in research and evidence. It is reflective, so there is a continuous improvement.”

With a public health approach, says Densley, the current narrative of gun violence will change from a more single-minded approach, such as security only, to a more holistic approach, such as preparation and prevention.

A public health approach requires these four actions: (1) define and monitor the gun violence problem and implement interventions to prevent it, (2) identify the risk and protective factors, (3) test effectiveness of those interventions, and (4) assure widespread adoption of the most effective interventions. It is a holistic approach, says Densley, to solving this crisis.

But since Columbine, the focus has been on security and safety through a law-enforcement response and security-system approach. While focusing on these elements is still and will continue to be essential, addressing the problem as a public health crisis is crucial. In changing that narrative, as Densley suggests, a public health approach helps us understand the why and how of these events. We are at an inflection point where we can begin to implement guardrail prevention based on intervention and preparation to support existing security systems.

Jody Madeira agrees. A professor at the Indiana University Maurer School of Law and a member of Moms Demand Action for Indiana, a group that fights for gun safety, Madeira teaches gun violence from the perspective of a public health crisis. “People’s lives are cut short like they are with obesity or heart conditions,” she says. One the of the strongest arguments for treating gun violence as a public health issue, she says, is that you can apply epidemiology to it: “Epidemiology for gun violence says that we are going to track certain populations, the distribution of [gun violence], and control.”

Source: Gun Violence Archive

Let’s look at what has happened thus far. According to GVA, more than 40,000 gun-violence deaths occurred in the U.S. in 2021 through November, and we’ve experienced 652 mass shootings. (The 611 mass shootings in 2020 were a 47 percent increase over 2019, which itself saw a 25 percent increase over the previous 5-year average of 334 mass shootings.) In Indiana’s 9th Congressional District, we have experienced 160 deaths to gun violence since 2013. Thoughts and prayers aside, the increasing number of shootings is now, unfortunately, part of our social fabric as a nation.

What has become clear is that mass shootings occur with increasing frequency and are more deadly. But, often, counting the numbers depends on the definition used by the counting organization. According to the Rand Corporation, no standard definition for a mass shooting exists. Data used vary from researcher to media outlet to law enforcement agency. For instance, the Gun Violence Archive defines a mass shooting as a minimum of four victims shot, either injured or killed, not including the shooter.

The FBI does not define mass shooting at all, though they define an active shooting as an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a populated area. In fact, using a threshold of deaths at four is entirely arbitrary. As a result of varying definitions, the number of mass shootings as calculated on an annual basis differs depending on the definition. But the fact remains, mass shootings have become immersed in our cultural fabric and society has become inured to them. They have quite simply, says Densley, “become part of our daily lives.”

In their book ‘The Violence Project: How to Stop a Mass Shooting Epidemic,’ researchers Jill Peterson (left) and James Densley outline several key patterns about mass shooters: They often experienced abuse or exposure to violence at an early age, often at the hands of their parents; parent suicide was common; and domestic violence and severe bullying by classmates were also predictors. | Courtesy photos

Since Columbine, law enforcement and security in the aftermath of a mass shooting have become the main focus. According to a 2018 Washington Post article, school security is a $2.7 billion business. As a nation, we have spent money on locked doors, cameras, bullet-proof whiteboards, transparent backpacks, facial recognition software, warning systems, metal detectors, and active shooter response training. But the big question is, do they really prevent mass shootings?

According to Everytown for Gun Safety, more than 95 percent of American schools have trained for and conducted active shooter drills, even though limited proof exists that suggests they work, and, in fact, evidence exists that they may be traumatizing for the mental health of children, teachers, and even parents with increases in anxiety, depression, and stress.

As for metal detectors, the evidence is similar. In the 2015-2016 school year, the WestEd Justice & Prevention Research Center reported that only 4.5 percent of schools used random metal detectors in schools despite the fact that, since the 1980s, schools had been regularly installing metal detectors as a security measure. They found that while “metal detectors may provide a visible response to concerns about school safety, there is little evidence to support their effectiveness at preventing school shootings or successfully detecting weapons at schools.” The U.S. now has a generation of students who have grown up with lockdown drills, active shooter drills, and metal detectors for active shooting situations.

It could happen anywhere

But mass shootings don’t occur only in schools. In their book, Peterson and Densley say that because 28 percent of all mass shootings occur in offices, factories, and other places of business, insurance companies may encourage or even mandate security training for the workplace. Despite this, not all businesses believe that it is necessary, even though Professional Safety, a journal by the American Society of Safety Professionals, estimates the cost of workplace violence to be $130 billion annually.

Dwight Frost, vice president and security branch director of Vantage Point Consulting: ‘The majority of businesses are not prepared, and yes, it is a large cost to do realistic training, especially with a high turnover rate that some businesses incur.’

Dwight Frost, vice president and security branch director of Vantage Point Consulting based in Indianapolis, says some businesses spend less than $2,500 on preparation. Some pay zero. “Many businesses add secure doors and cameras to entrances and call it good,” says Frost. “[This is] far short of what needs to happen to prepare for a mass shooting.”

Most businesses consider themselves to be a minimal risk for a mass shooting, says Schweit, and some companies believe that if you can’t make any money on security, why spend money on it. The FedEx shooting in Indianapolis in April proved that any business is at risk, even with security measures like metal detectors and security turnstiles in place. The FedEx shooter, a former FedEx employee, killed nine people and injured seven others, some outside the building in the parking lot.

But has the FedEx shooting motivated more businesses to up their security and intervention? “No,” says Frost. “The majority of businesses are not prepared, and yes, it is a large cost to do realistic training, especially with a high turnover rate that some businesses incur.” Businesses, like schools, must do the same training every year to be effective, he says. “I equate this to learning to do a fire drill as a child.”

Does security alone prevent a mass shooting? No. But preparedness does, says the BPD’s Oldham. “Preparedness is a key factor for deterrence,” he says. “Preparedness does two things. By being prepared, you have taken action and heightened awareness to be prepared.”

Early intervention as a way to prevent violence

In every public safety situation, our fight-or-flight response is to turn to law enforcement and a physical-safety response. That is just natural. Sure, security and security training are necessary components to manage a mass shooting. But if we’ve spent our way to increased security, why haven’t mass shootings stopped?

According to Schweit, even with all this increased security, mass shootings still occur, on average, every two weeks. The question becomes, is it time to examine the possible root cause of mass shootings, and if so, how?

To get to this point, we must, says Peterson, discuss prevention on three levels: in our individual lives, with our institutions, and on a societal level.

“To prevent violence, you must first understand the pathway to violence,” Peterson says.

‘The Violence Project’ examines evidence-based strategies to stop mass shootings. Authors Peterson and Densley used first-person accounts from the perpetrators, the people who knew them, shooting survivors, victims’ families, first responders, and leading experts.

As Peterson and Densley lay out in The Violence Project, to start with, we must understand mass shooters are individuals who have had trauma in their lives and are in crisis. They may be suicidal. They may be leaking their plans to others on the off chance that someone will stop them. They are becoming radicalized online. All these things, says Peterson, are indications of the road they have chosen to go down. What you have to do, she says, is “build prevention and intervention at each of those points along the road.”

In their research and interviews with perpetrators, Densley and Peterson outline several key patterns in their book. One was that 60 percent of mass shooters experienced adverse childhood experiences such as abuse or exposure to violence at an early age, and often at the hands of their parents. Parent suicide was common. Physical abuse, domestic violence, and severe bullying by classmates were also predictors.

Furthermore, 80 percent of all mass shooters reached what Peterson and Densley labeled “an identifiable crisis point” in the days, weeks, or months before the shooting. Some stressors — financial strain, a job-related matter, a fight with a girlfriend, or marital problems — pushed them over the edge.

Some shooters collected grievances like boys collect baseball cards. In her book Stop the Killing, Schweit calls these potential shooters “grievance collectors,” people who believe their only solution left is violence.

“A mass shooting is about showing [their] grievance to the world in this awful way and getting people talking about it and witnessing it,” Peterson says.

Another pattern was that prospective mass shooters might turn to previous mass shooters, study their behavior, and even identify with them because they are uncertain or suicidal. Often those models originate from the 1999 Columbine shootings.

Lastly — and this is why various legal and legislative avenues of security, such as red flag laws, background checks, gun safety regulations, or permit-to-purchase laws, are so important — mass shooters must have an opportunity to carry out the shooting that they have envisioned and planned. They must have access to people and places that represent their grievances. They must have ready access to firearms. In fact, 80 percent of school shooters obtained their weapons at home from family members, as was allegedly the case in the recent school shooting at Oxford High School in Michigan.

Where can most of these patterns be identified? Believe it or not, at school. School is a critical component to intervention, says Peterson. “In studying the lives of perpetrators who didn’t have family members who were on top of things, or didn’t have communities of people for support, we saw time and time again that they do go to school,” says Peterson.

In many cases, schools use a threat assessment team or a crisis intervention team (the terms are used interchangeably). It’s an interdisciplinary team to assess and resolve non-emergency, potentially threatening future scenarios. According to researchers at the U.S. Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center, these teams are critical for early intervention into potential problems.

Threat assessment teams as a means of deterrence

In its 2021 report Averting Targeted School Violence, the U.S. Secret Service defines threat assessment as “best practice for preventing targeted school violence.” The goal is to help a student have a positive outcome for the student and community.

A threat assessment identifies when a student and/or adult has a grievance that might escalate to violence and how a threat assessment team can intervene to provide that student or adult with services that can de-escalate the situation not only for the present but for the future. Threat assessment teams can be adapted for use in businesses, places of worship, and other organizations.

In her book ‘Stop the Killing,’ Schweit calls some potential shooters “grievance collectors,” people who believe their only solution left is violence.

According to the 2018 Secret Service report Enhancing School Safety Using Threat Assessment Models, threat assessment teams evaluate and resolve non-emergency situations. An interdisciplinary team meets regularly with parameters developed for evaluating these types of concerns.

The key findings of the report Averting Targeted School Violence found that targeted school violence can be preventable when concerning behaviors are identified and reported. Concerning behaviors may include a sudden change in appearance, mental health issues, talk of or plans for violence or suicide, withdrawal from peers, reckless behaviors, fascination with firearms or an escalation in target practice or weapons training, and sudden changes in social media conduct and other activities. The school intervenes before legal consequences are necessary.

Peers, other students, teachers, and coaches are best positioned to identify these signs and report the concerning behavior. The role of a parent is also critical. Sometimes, the school resource officer may be involved, especially if the goal is to keep students out of the criminal justice system. A school resource officer, or SRO, is generally a trained law enforcement officer tasked with safety and crime prevention in schools or a school district.

The critical aspect of a threat assessment/crisis intervention team, according to Schweit, is to have broad representation within the team so they can evaluate behaviors as a whole, helping them gauge whether or not this is a bigger or lesser problem over time.

“If you put together a team only during an emergency, they have no perspective,” says Schweit. “The team needs people who have the ability to affect change and who can take care of someone who is under duress.” Plus, these efforts take time and continuing attention, says Schweit, because you may have a student who needs to be managed in school over several years to make sure that they get on the right path.

Like any grasp for solutions, threat assessment teams are not without controversy. Some opponents argue that threat assessment teams entrench law enforcement protocols with school safety. Others claim that threat assessment teams are merely a Band-Aid on a refusal to address what some see as the real problem — mass proliferation of guns in the U.S. On the other hand, proponents say that, done correctly, threat assessment with interdisciplinary teams that include mental health expertise, established procedures, and training can be a tool to identify and get the help needed for a student in crisis. But they add, as with any attempt to solve a serious problem, a multifaceted approach is often necessary, so threat assessment teams alone are not a panacea to solving gun violence.

For organizations wanting to form a threat assessment team, Peterson and Densley have created a website, the Off-Ramp Project, which provides resources, training, and sample policies for anyone looking to train on threat assessment/crisis intervention teams. It also includes references to regional services.

Threat assessment teams at local schools

DeeDee Dayhoff, assistant dean for Student Services and Concerns at IU: ‘We try to encourage anyone with a concern about a student to fill out the Care Referral.’ | Photo by Chris Howell

At Indiana University, if a student exhibits concerning behaviors, the IU Division of Student Affairs Care Team works closely with its Threat Assessment Team and the Indiana University Police Department, says DeeDee Dayhoff, assistant dean for Student Services and Concerns. Meeting weekly, they act on student and faculty observations or anonymous reports of students who may need mental health services through their Care Referral System. “We try to encourage anyone with a concern about a student to fill out the Care Referral,” says Dayhoff. “There are certainly situations in which faculty, staff, and others will call to consult first and talk through their concerns as it might be in a more urgent situation.”

If a student is an imminent safety threat or a victim of a crime, then IUPD gets involved. “We do welfare checks on students through IUPD with referrals from the Division of Student Affairs,” says Deputy Chief Shannon Bunger. “There is always someone there that can help.”

The Richland-Bean Blossom Community School Corporation relies on an internal team to identify students who may need support. The team identifies needs and follows up with students. “We do have an internal team at each building that meets to discuss the needs of children who have been referred by staff,” says Matt Irwin, the business manager at RBBCSC. “That consists of our director of Student Services, counselors, school psychologists, building administration, and other staff members.” If there is a safety concern, an administrator will discuss it immediately with parents, Irwin says. The school district also has an internal threat assessment team.

Indiana University Police Department Deputy Chief Shannon Bunger: ‘We do welfare checks on students through IUPD with referrals from the Division of Student Affairs.’

Like Richland-Bean Blossom, the Monroe County Community School Corporation (MCCSC) has a similar committee, which it calls a “safety committee,” and every school building has its own safety committee. These committees comprise representatives from MCCSC, state and local law enforcement, fire department, emergency management, IU Health, public health, juvenile probation, and mental health agencies.

The value of See Something, Say Something

In the FBI’s A Study of the Pre-Attack Behaviors of Active Shooters in the United States, researchers found that 56 percent of the time, shooters leaked to a third party their intentions to commit violence. For those shooters 17 years old and younger, 88 percent leaked information about their plans. In the recent Columbine copycat plan in Florida, the two middle schoolers repeatedly expressed their intent in classes, the cafeteria, and Zoom meetings to conduct a school shooting. And The Associated Press reports that, hours before the shooting at Oxford High School in Michigan, the shooter’s parents were called to the school “for behavior in the classroom that was concerning.”

Having a system that allows reporting of concerning behaviors is a critical mechanism in early intervention actions for a threat assessment team. But Schweit says members of the community — students, parents, and others — need to play their part. People need to be trained on what to look for and whom to call with their concerns. “For five years, I have worked on supporting local law enforcement’s ability to respond,” says Schweit. “But now I think that responsibility is more with the community.” The problem, says Schweit: Most people don’t report.

In the FBI’s A Study of the Pre-Attack Behaviors of Active Shooters in the United States, researchers found that 56 percent of the time, shooters leaked to a third party their intentions to commit violence. For those shooters 17 years old and younger, 88 percent leaked information about their plans.

As much as 80 percent of the time, people know about a concerning behavior but still don’t report it because they second-guess their reasons, Schweit says. They don’t want to be a tattletale or to believe that the person could do anything wrong. A trusted reporting procedure makes it easier to “see something, say something” anonymously, while protecting the privacy of the person reporting. Making it simpler to report and making it anonymous help facilitate prevention.

IU’s Care Referral System and Indiana K-12 schools’ Safe2Say Something (originally developed by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the national nonprofit Sandy Hook Promise) support those efforts. These systems, especially with text messaging, allow students and others to make anonymous reports about behaviors. IU’s Dayhoff is encouraged. “The Care Team has seen a steady increase in referrals over the last several years, almost 3,000 for spring 2021.”

Putting the onus on the community to keep their community safe is a critical deterrence mechanism, says Schweit. “About 40 percent of people in mass shootings commit suicide. If you would stop a friend or a family member from committing suicide by making a call to an employer, pastor, or police officer, why wouldn’t you make that call to save somebody from doing something that might kill that person and others who are innocent?”

Student support services versus a law enforcement presence in schools

One of the challenges of delivering mental health services to students identified with concerning behaviors is that often those services are not available. When Indiana approved $19 million in state grants for the third year in a row for school security, only $642,000 was allocated for student- and parent-support services. The rest was earmarked for security.

According to the recent report Cops and No Counselors from the American Civil Liberties Union, more than 80 percent of youth who need mental health services couldn’t get those services in their communities because the services are inadequate. So, 70 to 80 percent of students turn to schools for help even though help may not be there.

The report also includes the following data:

- 1.7 million students attend schools with a police officer for security but no school counselors.

- Three million students attend schools that have a police officer but no school nurses.

- Six million students attend schools that have a police officer but no school psychologist.

- Finally, ten million students attend a school that has a police officer but no social workers.

Sadly, these numbers fail to meet even the barest minimum. Over 90 percent of public schools failed to meet professional standards for counselors, school psychologists, and social workers. The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250 students to one counselor. But in Indiana, the balance is 532 students to one counselor. The proportion for MCCSC schools is higher, using 2020-2021 enrollment numbers: 1 counselor to 588 students.

For MCCSC social workers, the ratio is also 588 students to one social worker when the recommended ratio is 250 to 1. MCCSC employs seven school psychologists with a ratio of 1,597 students to 1 school psychologist, when the recommended ratio is 500:1. Improving these ratios has been something MCCSC has been working on, says Kelby Turnmail, communications officer at MCCSC. “Over the last few years, MCCSC has increased our school social workers, school psychologists, counselors, and mental health support staff in the buildings,” Turnmail says.

They also used funds from a Lilly Endowment grant to focus on students’ social emotional learning. “Our team does a fantastic job building relationships with our students as a part of their social emotional learning and are there to help with any questions or concerns they may have,” says Turnmail.

Yet, on the flip side, since 1998, the U.S. has spent over $1 billion to increase police presence in schools. The National Association for School Resource Officers (NASRO) estimates that approximately all K-12 schools have about 14,000 to 20,000 school resource officers, based on U.S. Department of Justice information and NASRO training data.

And the question: Do they help? Well, the answer is mixed.

A 2021 California Law Review article, “The End of School Policing,” examined the question and found that few studies assess the effectiveness of school policing. Plus, whether an SRO makes students feel safe is often dependent on the student and their experiences with police, trauma, or violence; those students are often disproportionately Black and brown students who may have a different perception of law enforcement.

Whether a school resource officer adds to the safety of the school is often dependent on the training they have had. The president of the Indiana School Resource Officer Association, Chase Lyday, is a full-time SRO for Avon School District near Indianapolis. He has long advocated that Indiana should mandate NASRO training program for SROs in the state.

Chase Lyday, president of the Indiana School Resource Officer Association: ‘Understanding brain development and special needs means that an SRO can respond more appropriately to know how to physically intervene or speak or even to know when to back up and give the student space.’

In Indiana, a school resource officer is defined under Indiana Code as an individual who has completed minimum law enforcement training requirements and received at least 40 hours of training through the Indiana law enforcement training board, NASRO, or another SRO training program. An Indiana SRO must be assigned to one or more school corporations, protect against outside threats to the physical safety of students, prevent unauthorized access to school property, and secure the school against violence and natural disasters; they must also be employed by a law enforcement agency or appointed as a police reserve officer. Lyday estimates about 800 certified SROs currently work in the state.

But training methods are mixed in Indiana schools. Some schools, says Lyday, hire off-duty police officers who have no extra training about serving within a school environment. Lyday estimates that 2,000 to 2,500 police officers don’t have the training to work with schools. “That is not a model that we suggest using,” says Lyday. “They don’t fit my definition of an SRO. They don’t fit the state statute definition, and they don’t fit the federal definition.”

According to Lyday, if schools are going to have an SRO onsite, they must mentor students, educate staff and students, and be well-trained to deal with students in an educational setting. MCCSC’s school resource officer and security guards often serve as a resource to students, says Turnmail. “MCCSC has several well-trained school safety specialists throughout the corporation. They often serve as a resource that our students turn to when they have concerns for another student’s well-being or when they have concerns about school safety.”

Lyday says all SROs should undergo the 40-hour basic training program as advocated by NASRO. It covers the foundations of school resource officers, serving special-needs students, trauma-informed care, understanding trauma and violence effects, the adolescent brain and brain development, and many other aspects.

An SRO must understand the context in which they are making decisions to avoid escalating a situation, says Lyday. “Understanding brain development and special needs means that an SRO can respond more appropriately to know how to physically intervene or speak or even to know when to back up and give the student space.”

Despite all these proactive measures, we may still not be able to stop mass shootings in our lifetime. But with deterrence and preventive methods like threat assessment teams, reporting systems, and even well-trained SROs, experts say there is a chance at turning the tide. Gun violence is a problem that impacts each of us, which makes it a public health crisis in need of a public health approach.

As a long-time law enforcement officer, Schweit knows this well. “By the time that I interact with a person with a gun, the solution is quite different potentially than if we had tried to prevent that person from picking up a gun in the first place. Prevention is something, I think, that as a country we have not taken responsibility for on an individual basis.” But we have to start trying, says Schweit, because we can prevent mass shootings only if our society accepts the responsibility for preventing them.

Support Nonprofit News!

Limestone Post cannot publish this kind of in-depth, public-service journalism without the support of our readers. Would you consider a donation? Now through December 31, 2021, your monthly or one-time donation up to $1,000 will be matched by NewsMatch. Every donation helps! Thank you for supporting nonprofit journalism!

—Ron Eid, Limestone Post publisher