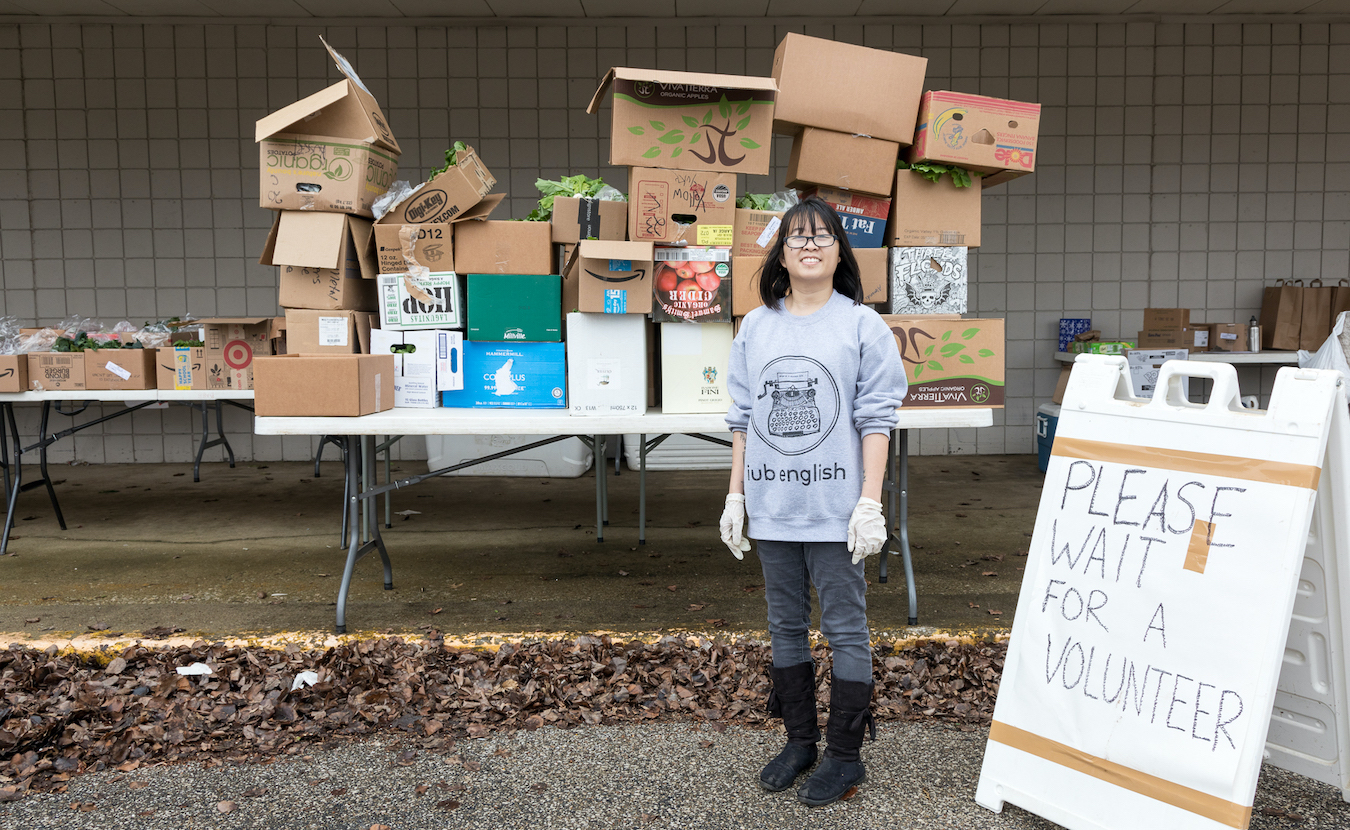

Chilly air, gray skies, and coronavirus worries did not dampen the buzz of the People’s Market launch on the morning of March 21. Gloved volunteers, bundled up in puffy coats and DIY face masks, loaded cardboard boxes of leafy greens, brown eggs, and seeded bread into the trunks of cars filing through the parking lot of the shuttered Kmart on East 3rd Street. Customers had preordered their selections online, avoiding the need for cash exchanges and direct physical contact.

On that Saturday, the People’s Market debuted a farmers market framework unprecedented in Bloomington and Indiana as a whole. As a champion of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), the People’s Market coordinates the selling and distribution of foodstuffs directly from purveyors to nearby consumers. It’s run as a cooperative of growers, small business vendors, and organizers who vow to hew to the “highest standards for valuing diversity and inclusion.” As highlighted on its website, “We strive to build equity, create relationships, cultivate liberation, and ensure access to local food, art, and education.”

People’s Market launched on March 21 in Bloomington as a cooperative of growers, small business vendors, and organizers to focus on food justice and mutual aid.

Its ambition foregrounds two related forms of political activity that aim to overturn existing patterns in our society that reproduce deep-seated race and class divides.

The first is food justice. Social scientists Alison Alkon and Julian Agyeman describe food justice as an approach embraced by African American communities and other people of color to “provide food for themselves while imagining new ecological and social relationships.” LaDonna Redmond and other food justice advocates call attention to the long-running connections between the production, distribution, and consumption of food and systematic race and class inequalities. The New York City–based organization Just Food underscores that food justice prioritizes “the power, health, and wealth of marginalized peoples.”

The second activity is mutual aid. Seattle-based progressive network Big Door Brigade offers a useful definition:

Mutual aid is when people get together to meet each other’s basic survival needs with a shared understanding that the systems we live under are not going to meet our needs and we can do it together RIGHT NOW! Mutual aid projects are a form of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions, not just through symbolic acts or putting pressure on their representatives in government, but by actually building new social relations that are more survivable.

Crucially, mutual aid volunteer efforts aim to solve problems that are created, worsened, or ignored by corporations and politicians.

With the People’s Market rollout, the ongoing Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market saga has taken an unexpected turn in the face of the COVID-19 emergency. Objections by anti-racist activists to the presence of neo-Nazi vendors at the city-run market escalated last summer. Following the arrest of one protester on July 27, Mayor John Hamilton famously shut down the usually bustling Saturday morning marketplace for two weeks. He cited as his rationale the “rising tension at the market and information identifying risks of specific individuals with connections to past white nationalist violence.” In its absence, Bloomingfoods Co-op pulled together a temporary market across town in the same Kmart parking lot adjacent to the co-op’s east-side location.

Bloomingfoods Co-op pulled together a temporary market at its east-side location last summer after Mayor John Hamilton shut down the Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market for two weeks in August.

In that moment, No Space for Hate, one of the main groups leading the call to ban white supremacy from the city-run market, quickly spearheaded “Fundraiser for Farms and Food Pantries” via the GoFundMe platform. With the collected monies, No Space for Hate began buying produce from “vendors adversely affected by reduced market sales” and donated it to area food pantries Community Kitchen, Pantry 279, and Shalom Community Center. By March 2020, No Space for Hate had collected $5,654.

To kickstart the double-sided drive, No Space for Hate consulted with Mallory Rickbeil, a local anti-hunger advocate. Several years ago, Rickbeil and Dustin Rathgeber, a local organic farmer (now deceased), began tackling an ongoing problem for Linton, Indiana’s farmers market: how to keep it going by attracting and retaining seasonal vendors as insurance against up-and-down marketgoer attendance. At the time, Rickbeil served as a community wellness coordinator covering Greene, Owen, and Clay counties for the Purdue Extension Nutrition Education Program. As part of her position, she had been collaborating with food pantries to provide unsold farmers market produce to area residents. Growers voluntarily donated “ten percent or whatever they could write off,” she says. “After a while, it felt exploitative to continue to ask these small vendors to donate perishable produce without making a good-faith effort to compensate them and provide support where I could.”

The City of Bloomington had already been developing a bigger program along these lines with its Year of Food campaign. Rickbeil says that she and Rathgeber tailored the concept “for small up-and-coming markets [as] a great opportunity to build partnerships and begin actively confronting the prevailing idea that households experiencing food insecurity should just be grateful for whatever junk food or scraps could be scavenged from Walmart produce write-offs.”

In one month, the number of suppliers at the People’s Market increased from 7 to 31, selling everything from produce, meats, eggs, and dairy to flowers, gardening materials, chai, coffee, chocolates, baked goods, and frozen treats.

They applied for funding to pilot “CRiSP,” a sustainable pipeline scaled to fit Linton. “Compensation Recovery for Surplus Produce is a term that is used [in] food system/agricultural research,” Rickbeil says. “I guess I added the ‘i’ to make the program name spell ‘crisp’ like the feeling of biting into a fresh fruit or veggie. But that to me doesn’t seem worthy of a naming credit.” She credits the insights of African American women, including those who started Indianapolis’s Black Farmers Market, for “opening my eyes to the systematic injustice of the local food movement,” she says.

Right after they received word in winter 2019 that CRiSP had been green-lighted, Rathgeber died in an accident. Devastated, Rickbeil pulled the grant application and stepped back from the Linton market.

But when the temporary market sprang up last August in the abandoned Kmart parking lot, Rickbeil recognized the immediate need to “demonstrate that it IS possible to support local food movement AND reject a culture of white supremacy,” she wrote in an email. She shared the CRiSP blueprint with No Space for Hate and other organizers eager to support “vendor allies in the cause.”

The stopgap scramble spawned the Eastside Market, a self-described “all inclusive” venture. Of the dozen or so vendors, some had left the city-run market while others were newcomers to the local scene. The pop-up operated on Saturdays at the Bloomingfoods East location from August through mid-March, flanking the parking lot next to the picnic tables and moving indoors to the covered patio on rainy and cooler days. The offerings rotated: tamales, chili peppers, garlic, popsicles, coffee, baked goods, butterscotch candy, pickled and fresh vegetables, eggs, lamb. Foreseeing heightened food scarcity needs during fall and winter, Eastside Market reintroduced the CRiSP initiative in October.

All the while, market runners brainstormed ways to devise a long-term version of their improvisation. Fifteen women — a third of whom are BIPOC (Black and/or Indigenous and/or People of Color) — began meeting regularly to hammer out the logistics for what would become the People’s Market.

Abby Ang and another volunteer help a customer at the People’s Market CSA drive-thru on March 28. Writer Ellen Wu reports that from the first week to the fourth week (April 11), the number of boxes sold increased from 173 to 654, with the number of boxes bought for donations increasing from 58 to 167.

The People’s Market planning committee has embraced collaborative and democratic guiding principles from the outset. First and foremost, this entails setting up a cooperative governance structure where decision-making power belongs to “people from marginalized communities, farmers, and vendors.” Lauren McCalister, who owns Ellettsville’s Three Flock Farm with her husband, Brett Volpp, has taken the lead in this regard. She has tapped into guidance on developing co-ops from the Indiana Cooperative Development Center, including materials to train and educate both sellers and consumers. In her view, vendor-run cooperatives allow farmers to “participate in a new way, getting more benefits that are going to increase the longevity of their farm.”

This is precisely what attracted Susan Welsand, aka The Chile Woman, to join. In her 28 years of selling chili peppers at the Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market, she says, “one of my frustrations there was that the vendors had so little say in how the market was run.” By contrast, “This type of cooperative model where the vendors can set policy appealed to me so much.” Welsand smiles confidently. “I am all in.”

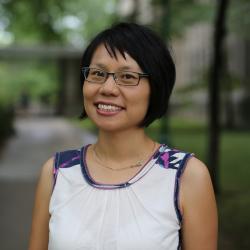

The People’s Market prizes “inclusion” and “access” as fundamental values. At one level, this necessitates an unequivocally “Nazi-free space,” one that is explicitly “anti-racist,” as planning committee member and No Space for Hate convener Abby Ang puts it matter-of-factly.

Yet its mission to “create spaces that remain welcoming, inclusive, and accessible” means even more than keeping avowed white supremacists at bay. It demands expanding the notion of “access.” As McCalister points out, “Often in food sustainability [discussion and policy], it’s about the consumer’s access. What I’m saying as a black person is that I don’t have access to grow food, I don’t have the access to produce a product, I don’t have the access to show up at the marketplace.” For the planning committee, “access” for producers translates to reducing financial risk by lowering vendor participation fees and accepting payments month to month rather than requiring lump sums at the beginning of the market season, and by building flexibility into their structure. The idea, Welsand says, is to “find a way to work it out [so that] whoever wants to participate can participate.”

Brandi Williams (left), owner-operator of Primally Inspired Eats, and Lauren McCalister, owner of Three Flock Farm in Ellettsville, are People’s Market committee members.

The commitment to “access” loosened the planning committee’s approach to setting up the market format — i.e., the points of contact between sellers and buyers. The coordinators initially intended to implement an “on-the-ground market,” explains Brandi Williams, committee member and owner-operator of Primally Inspired Eats. Even so, they entertained different possibilities for how that might function, including multiple locations beyond downtown to increase access for customers. “Access is a conversation about social justice,” McCalister says.

They considered many angles. “What does a co-op model look like?” Williams says. “Does it look like an old-fashioned farm stand with everybody’s product sold at one table? Does it look something like a food-stop model with multiple locations in food-desert areas or in marginalized communities? These were conversations already taking place behind the scene for what our goals were to evolve into beyond just an on-the-ground farmers market. The whole goal was to have more access to fresh local food, and how do we do that, how do we get creative about it.”

This exploratory thinking prepared the planning committee to reorient swiftly to the drive-thru CSA once it became obvious that COVID-19 would upend everything. Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb declared a public health emergency with the state’s first documented COVID-19 case on March 6. On March 10, Indiana University suspended in-person classes until April 5, before eventually canceling all in-person campus activities through the end of the spring semester, including commencement. Monroe County Community School Corporation followed suit the next day, and the Monroe County Public Libraries closed the day after that. On March 12, the Bloomington Winter Farmers Market, which was held on Saturdays at Switchyard Pavilion, announced that it would halt at least momentarily to abide by Holcomb’s directive to limit “non-essential” gatherings to 250 or fewer attendees.

Stunned, the planning committee “immediately shifted gears, brainstorming ‘How do we get good quality food safely to people, how do we get farmers paid,’” says Welsand. “No one expected that,” adds McCalister.

Eastside Market held its final on-the-ground marketplace on Saturday, March 14. The planning committee pushed up the People’s Market kickoff date from April 4 to March 21. On March 16, the People’s Market announced on Facebook and Instagram: “In response to the current ban on large gatherings The People’s Market (formerly Eastside Farmers’ Market …) has organized The Community Share CSA to give you the opportunity to buy local produce and support local farmers.”

“I think those nuggets of inspiration were already there when COVID-19 hit,” Williams says. “It wasn’t easy, but in a sense we could pivot quickly to ‘What does it look like to not have an on-the-ground market,’ because of the conversations we were creatively already having in the background. It created an opportunity to meet the community’s needs, to meet the community where they were at. And where we’re at right now is in a really challenging place.”

Pivoting during a pandemic

While it likely takes an incredible amount of forethought and labor to run a CSA under normal circumstances, it’s exponentially more so at an accelerated pace during a pandemic shot through with uncertainty. The hazards of the current emergency require streamlining deliveries and minimizing in-person contact. Thus, much of the groundwork takes place online by necessity. A behind-the-scenes technical crew set it in motion. For the first four weeks, the People’s Market posted links on its social media feeds to a Google Doc order form. The links went live early each Monday morning, and customers had until 5 p.m. each Tuesday to place their orders. Invoices and detailed instructions for contactless pickups were sent by email late Tuesday evenings, and electronic payments were requested by 5 p.m. Wednesdays. A “virtual market” using Local Line software replaced the Google Docs on April 13.

At present, People’s Market relies entirely on monetary, time, and in-kind contributions to sustain itself. Planning committee member Megan Betz devotes twelve hours each week to coordinate orders and payments. “Right now a lot of my time, a lot of it, is going to invoicing. Prepping our invoices, making sure we get paid, and translating data in stuff that’s invoiceable.” She originally joined People’s Market to work on fundraising, and she has been grant-writing to seek additional support for the market’s infrastructure, such as PayPal processing fees. In late March, the planning committee submitted an application to Monroe County United Way COVID-19 Emergency Relief Fund to purchase sanitation supplies (gloves, disinfectants) and to hire a part-time market manager for three months. Their request was turned down, but they are applying to other to sources as well.

Ang and other individuals started No Space For Hate in 2019 to ‘work against white supremacy in Bloomington.’ When the Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market closed for two weeks last summer, No Space for Hate held a fundraiser to buy produce from area vendors and donate it to food pantries Community Kitchen, Pantry 279, and Shalom Community Center.

Abby Ang estimates that she spends 15 to 20 hours each week coordinating volunteer workers. They do everything from making phone calls and sending emails to collecting castoff cardboard boxes and egg cartons from businesses around town. Every Saturday, 15 volunteers work from 7 a.m. to 2 p.m. to set up tables and tents, receive food from vendors, pack boxes, staff the drive-thru, and deliver items for donation. More people are willing to help, Ang says, but it’s too risky: Social distancing adds a “layer of stress.”

Bloomington resident Lisa Meuser began promoting the Eastside Market last fall and eagerly signed up to volunteer. One recent Saturday, she stood for several hours waving a CSA sign in the Kmart parking lot, directing customer traffic, and fielding questions from curious passers-by. Meuser says she is drawn to the venture for its “integrity.” In her view, People’s Market is based in the same spirit of mutuality that has burst open throughout the Monroe County area recently. “They were already seeing that there’s a crisis. Before COVID-19, they were seeing that people were being excluded, they were seeing the injustice, they were seeing the need, they were seeing the exclusivity, so they rose to the occasion.” To Meuser, the planning committee members are visionaries. “They’re the trailblazers of the community,” she says. “They have amazing hearts — kind, loving, generous hearts.”

April Hennessey of Bloomington echoed Meuser’s sentiments on social media after completing a volunteer shift. “I did some deliveries for the People’s Market today, and as I was driving around, I reflected on the truly staggering amount of organizing and labor that Abby Ang and crew have done over the past few weeks, not only with the People’s Market but with the Mutual Aid site [Monroe County Area Mutual Aid for COVID-19], as well…. Abby Ang, you deserve much more than a Facebook callout. Truly. … And someone from the mayor’s office ought to give you a damn medal for doing the work (again) that they refuse to do.”

A distinctive feature of the People’s Market is its sponsorship program “for those at risk of hunger and food insecurity, or for whom participation in [the] market is cost-prohibitive.” Initially, subscribers could purchase boxes of produce ($15), egg and bread boxes ($10), desserts ($5), cheeses ($10), meats ($40), and cold-hardy, garden-ready plant starts ($10) for themselves or for sponsorship. But the options continue to grow with the virtual market. Customers may also donate money directly to People’s Market.

The community has responded enthusiastically to the “get a box/give a box” sponsorship program. The data tells the story. Week One (“the trial week,” Williams calls it, to “prove we could do it”) saw 173 boxes purchased, with 58 boxes (34 percent) on sponsorship. Week Two jumped to 377 boxes ordered, including 158 sponsored boxes (42 percent), and a waitlist of 50 people to buy produce. “Our demand is huge,” Betz says. Week Three brought 618 purchases; 185 (30 percent) of those were donated. And Week Four (April 11) held steady. Out of 654 boxes sold, 167 (26 percent) were earmarked for donation. The total gross for April 11 was $9,000, with $8,000 going directly to vendors and the remaining $1,000 received from direct giving ($2 suggested per box to cover the People’s Market’s overhead).

“What I think is really interesting is that the people are purchasing produce, they’re purchasing eggs and bread, they’re also purchasing desserts on sponsorship,” says Betz. “There’s not this ‘You are this poor person, I’m going to tell you what you need for your household.’ There’s a real humanizing element to it. People are buying this so that folks get to enjoy the full spread of what we have to offer.”

Where do the donated boxes end up? Some find their way to families who request them directly. Others have landed with various organizations around Monroe County that serve people subject to food scarcity, including New Hope, Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard, Community Kitchen, Monroe County Food Train, and Pantry 279.

Nichelle Whitney, senior assistant director for IU Admissions and the commissioner for Monroe County Women’s Commission, birthed the Monroe County Food Train to feed “under-resourced communities” impacted severely by the COVID-19 shutdown. “We are seeing the demand grow every day,” Whitney says. “This is why donations from partners such as People’s Market is essential for sustainability.”

Cindy Chavez, director of Ellettsville’s Pantry 279, confirms the impact. After the No Space for Hate and Eastside Market booted up the CRiSP program last year, “people were really excited,” she says. Some clients even switched their pickup days to Saturdays so they could choose from Eastside Market selections. “Produce is weird,” Chavez says. “It just depends on what the stores donate, what stores have decided is not yet shelf-fit… [With] People’s Market stuff, we don’t get the day-old stuff. It’s very, very fresh. Most of it’s organic. This is something most of the people that we serve, they would never ever get a chance to purchase on their own. Most of them can’t afford produce at all.” Saturday drop-offs are an added bonus, because Pantry 279’s other provider (Hoosier Hills Food Bank) delivers only on weekdays.

Committed to inclusion and access

Alongside donations, expanded access for the People’s Market means participating in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). SNAP provides low-income Americans subsidies to encourage “healthy food” purchases. Enrollees may utilize Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) debit cards at authorized farmers markets. Planning committee member Angela Babb worked to get approval for People’s Market to accept SNAP EBT payments. “I decided to dedicate my time to setting up SNAP because it is such a critical program for so many folks in our community,” says Babb. “We [the People’s Market] feel strongly that SNAP is necessary for an accessible and inclusive food market, and so we prioritized it. I also chose to work on SNAP because I have been studying the SNAP program for eight years and realized this was a way for me to put my knowledge and interests to good use for the People’s Market.”

To make SNAP happen, People’s Market has partnered with Artisan Alley, a 501(c)3 nonprofit artist collective in Bloomington. Artisan Alley agreed to take this on because “their intentions and mission aligned with ours,” says Executive Director Adam Nahas. Artisan Alley extended to People’s Market an “organizational membership, which gives them the use of our resources,” as well as “fiscal sponsorship.” This arrangement allows People’s Market “the coverage of our nonprofit umbrella so that they could operate their CSA program, accept SNAP benefits, and begin their journey.”

People’s Market’s SNAP goal for now is to offer an approach that has proven successful at farmers markets around the country: doubling the value of EBT “dollars” so participants can purchase goods at half price. SNAP is location specific, and People’s Market hopes to eventually make it available at multiple locations to ease transportation hurdles for potential users. EBT will be enabled when the debit-card machine reader arrives. “Unfortunately, the outbreak has caused UPS to hold our EBT machine hostage until further notice,” Babb says.

Perhaps the most telling indicator of People’s Market’s promise is the growing interest among vendors. At the end of the last farmers market season, Welsand “put out feelers” to find out who might be interested joining. The positive response was encouraging, if somewhat unexpected.

“Of course we’re surprised,” declares McCalister. “There were a lot of naysayers out there.”

For months, Williams says, the planning committee heard a range of reactions. While some people were “completely inspired and supportive,” Williams says, not a few others criticized the new market project as “unneeded,” even “divisive.” But with the shifting circumstances, “we’re proving right out of the gate that we have the ability to meet these needs.”

Again, the numbers are revealing. In just one month, the roster of suppliers has exploded. People’s Market started March 21 with seven vendors. When they opened the online store on April 13, the website listed 31 suppliers selling everything from fresh and preserved produce, meats, eggs, and dairy to flowers, gardening materials, chai, coffee, chocolates, baked goods, and frozen treats.

Customer feedback suggests that People’s Market may well continue to grow. Their Facebook reviews are uniformly glowing. For example, area resident Nate Johnson posted on March 26: “The People’s Market is fulfilling the dream of a true food justice movement. Against factory farming. Against climate devastation. Against eco-fascism. Thank you for your commitment to justice and to community, People’s Market! [heart emoji].” Journalist Dave Askins, who publishes B Square Beacon, included this report in his weekly subscriber newsletter dated April 13: “My pickup from the alternative People’s Market CSA, went slick as snot on a glass door knob, as my old shop teacher at Northside Junior High School in Columbus, Indiana, used to say. Had about a 15-second wait for my eggs, bread and dessert.”

While nothing is certain with the coronavirus quarantine, planning committee members nonetheless look forward to hosting a face-to-face market at some point in the future. “I still like the idea of a having the physical market space where people can gather,” Ang says. “I didn’t think I would be so thirsty for human contact — [at] two weeks in [to the COVID-19 emergency]. I’m already starting to feel it.”

Whatever form the People’s Market takes post-pandemic, the founders are adamant about one thing. “We [are] interested in something beyond just re-creating the city market, because those goals and values are different,” McCalister says. “It’s assumed that we will be doing things different, and I think that’s the mentality that keeps us vibrant.”

Betz sums it up: “This is not an alternative food project. This is questioning how food is structured and rebuilding those models. If you push it to the center, then the system has to change.”