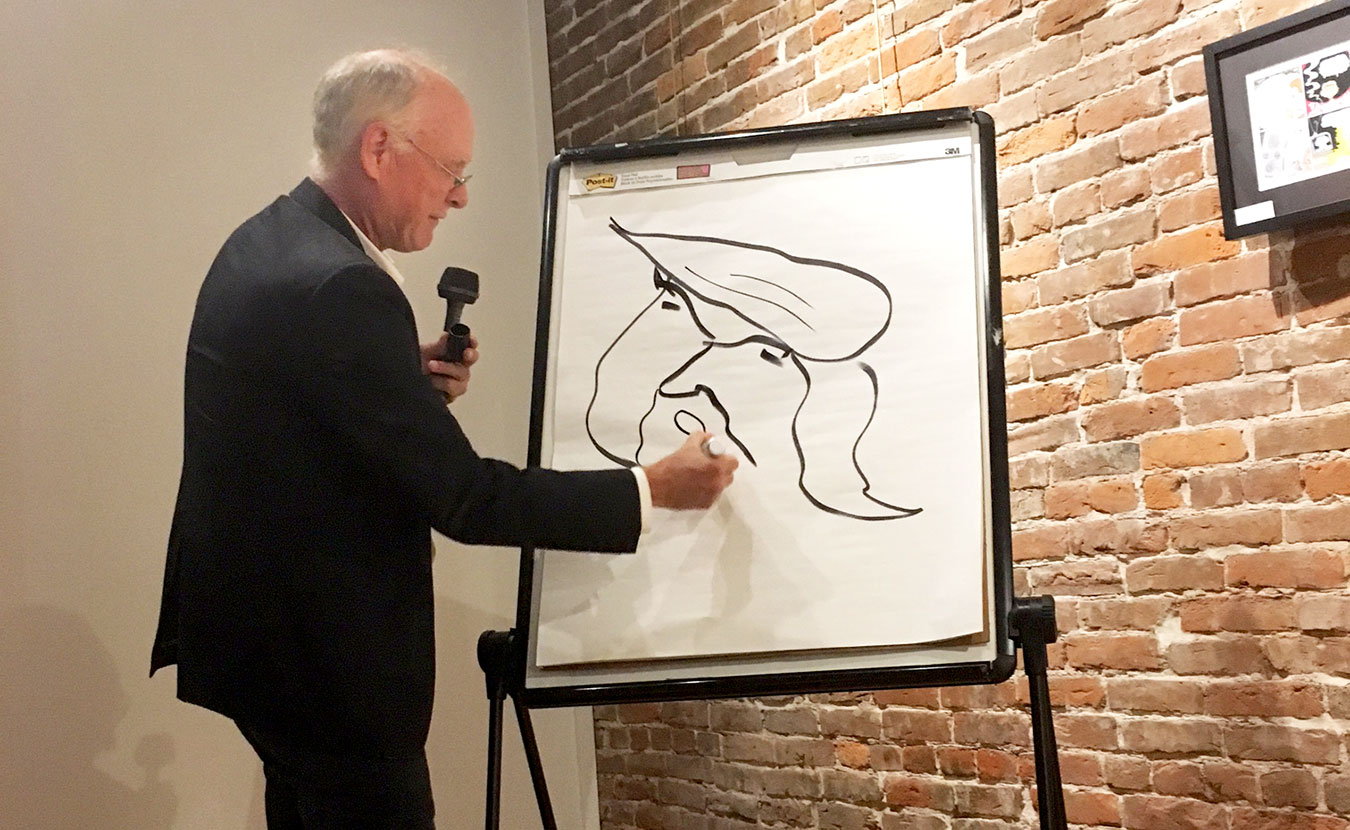

Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and Bloomington expat Joel Pett returned to his hometown recently for a gallery show — and a stand-up gig at Thomas Gallery. | Photo by Devta Kidd

Joel Pett has been called every name in the book. In fact, he’s recorded some of them. Last Saturday night, about 50 people crowded into the Thomas Gallery on the downtown Square to listen to Pett’s voicemail.

[Editor’s note: Strong language ahead!]

“You are hateful and mean,” we heard one woman telling Pett’s machine.

“You are a real piece of shit,” said another caller.

We were just getting warmed up. The tape was part of Pett’s stand-up routine, a kind of verbal interlude while Pett was backstage changing out of the Donald Trump get-up he’d donned for a quick sketch at the beginning of the show. Before coming back out for the rest of his set, he let the messages roll over some whimsical music:

“Joel Pett, how could you do what you did?” another indignant voice importuned over the line. “I know you liberals are lowlifes, but I never realized how low.”

The insinuations only got worse.

“We don’t need you here in Kentucky causing problems for innocent children,” someone said.

“I’ll be calling the publisher to ensure that you get fired,” reported another.

“I don’t even know what to say,” admitted one exasperated caller. “I’m so pissed. Thank you and go to hell.”

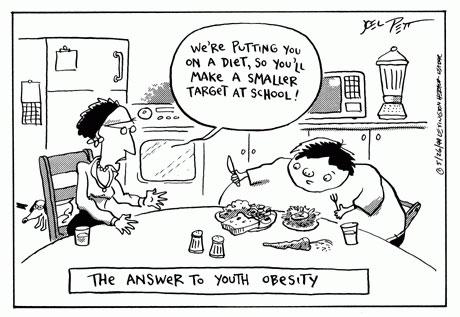

After 35 years as an editorial cartoonist for the Lexington Herald-Leader, the Bloomington expat is not only inured to this sort of thing, it obviously amuses him. And how surprised could he be about the outrage anyway? This is a guy who, in his 1999 strip “The Answer to Youth Obesity,” seemed to suggest that kids slim down so that they’d fare better during school shootings.

If you’re able to produce something like that, you’re able to take some name calling. But there is one name I could sense he really didn’t like being called. So when it was just us in the gallery, I went ahead and brought it up.

“Do you say, ‘I’m an artist’?”

Image courtesy of Joel Pett

My question felt pretty darned disrespectful. I mean, maybe if I’d questioned his status as a stand-up comedian it wouldn’t have been out of line — tonight was one of just a handful he’d spent telling jokes onstage. But the guy had won the Pulitzer Prize for stuff he’d drawn. So who was I to question his professional identity? Still, there was something about his absence of preciousness that made me think it would be okay to ask.

“No,” Pett shot back. “Never. I have no art training, no particular skill, I can’t work with weight or perspective.”

“You’re very self-deprecating about your facility,” I said.

“With good reason,” he replied.

Although somewhat relieved he hadn’t taken my question badly, my sense of cognitive dissonance was only growing. If you’ve been anywhere near an op-ed page since the second Reagan administration, yours would be, too. Or maybe I should expand that to say “anywhere near newsprint.” Or the internet. You would have to try hard to avoid Pett’s cartoons, which have been syndicated in the print and online versions of everything from The New York Times and the Washington Post to the Los Angeles Times, USA Today, and Newsweek. The winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning in 2000, Pett was also named finalist for the award in 1989, 1998, and 2011.

Just don’t call him an artist.

“Cartooning is this amalgam of writing and drawing,” he told me, by way of explanation, “and in the field — from the comic strip artists to the newspaper guys to the greeting card people to the animators — there are people who are artists who have learned to write, and there are writers who have learned to draw, and that’s what I am.”

During Pett’s performance at Thomas Gallery, he did a drawing demo, showing the audience his shorthand for rendering the last six presidents. | Photo by Devta Kidd

Which maybe explains why Pett has undercut the fine arts vibe of having a gallery show by doing a stand-up routine the night after the opening. It’s just so much gilding of a lily. Unlike their performing counterparts, visual artists usually do their work in advance, without an audience. All an artist really needs to do in the gallery is stand there and look pretty. Which Pett didn’t exactly enjoy, apparently.

“It’s a colossal pain in the ass,” he groused. “I dunno — I don’t like standing around.”

He got talked into the exhibition by Tom Gallagher, the owner of Thomas Gallery and an old friend of Pett’s from the go-go years of the Bloomington Herald-Telephone. While Pett was working in the paper’s art department in the late ’70s, Gallagher was in sales — an aspect of the business Pett still isn’t crazy about. He sold some prints at the Friday night opening, reluctantly.

“I didn’t enjoy selling those posters,” Pett admitted. “It was like when I walked down to the Fourth Street art festival today. It seems really sad — everybody with their stuff, and nobody wants it. Like one person in a hundred. We sold a bunch of posters, but all I could think when I went to sleep was all those people who looked at that poster, and said, ‘I don’t want that fucking poster.’”

Image courtesy of Joel Pett

“Why would you have that feeling?” I asked.

“Because I’m a glass-half-empty kind of guy,” Pett replied. “Just a pessimist.”

“You have to be in this line of work, right?” I suggested. “To be a satirist, you have to be that way, don’t you?”

“I guess,” Pett shrugged. “Although not all of them are.”

“Maybe not Family Circus,” I said. It was just the most anodyne comic I could think of off the top of my head. Turns out Pett had done some serious skewering of that very strip.

“You know,” he said, “I was invited to roast him at his retirement party at the World Trade Center in 2000.”

Holy cow. That’s like asking Iggy Pop to speak on behalf of Kenny G or something.

“It was the biggest room I’ve even been on a stage in,” Pett said. “There were 700 people in tuxedos in this ballroom in the World Trade Center. Saying goodbye to Bil ‘Family Circus’ Keane.”

“It’s bewildering to me how that thing has had such longevity,” I said. “And I’m curious what on earth you would have said.”

“I just shit on it and said all the reasons it’s such a piece of crap. ‘What the fuck? You’re sending Jeffy out for the paper on a dotted line and he kills a turtle and climbs a tree and fucks a hooker and sells some crack and comes home. And you do that, what, once a month?’”

Knowing that Keane had invited Pett to roast him almost made me respect Mr. Family Circus. When I was a teenager, I sought refuge from the Sunday comics in the free weeklies, where I discovered Lynda Barry and pre-Simpsons Matt Groening. Family Circus — like Blondie and Cathy and For Better or Worse — was “the kind of cartoon for people like my mom,” I told Pett, “who thinks lampoons and satire are mean. She thinks doing an impression of someone is mean.”

Images courtesy of Joel Pett

“It is mean,” Pett confirmed, “and so is doing a caricature. But you know what? Fuck you, Donald Trump. You ran for president and now we can’t do a caricature?”

In other words (and with apologies to Marshall McLuhan) the message — and not the medium — has always been the message for Pett. “I’m just an angry person who needs some kind of outlet to express my grief about how fucking stupid we are.”

But there are so many ways to express that feeling. Rock and roll. Zine publishing. Street theater.

“Why did you choose this medium, then?” I asked, hoping for an excursus into the poetics of line or at least a reference to Daumier, Hogarth, or another of the legendary satirists from the history of art.

Image courtesy of Joel Pett

“I thought it was cool,” Pett replied. “No other reason. When I was a teenager, I looked in the newspaper, and thought, ‘Look, they’re shitting on Nixon. That’s cool.’”

My attempt to excavate Pett’s cartooning impulse for its visual roots was going nowhere.

“All that shit doesn’t interest me,” he said. “I’m interested in politics and people in power and how they use it and how it’s just so crazy that we have these brains that could make this thing [pointing to his iPhone] out of sand and metal, and we can’t, like, not have war. How can you be so bipolar as the goddam human race — so brilliant and so fucking stupid? And it hasn’t gotten any better. It’s gotten worse. I’ve wasted all my time bitching about stuff that can’t be changed. It’s been a complete waste of time and energy. A futile life.”

It is hard to know whether to take Pett’s misanthropy and nihilism at face value. In his 2009 book American Photojournalism, Indiana University Media School Professor Emeritus Claude Cookman traces the progressive impulse that underlies the social documentary tradition. Cookman — who himself was part of a team at the Louisville Courier-Journal and Times that won a Pulitzer Prize for “a comprehensive pictorial report on busing in Louisville’s schools” in 1976 — argues that such photographers as Jacob Riis and Dorothea Lange, for example, did not simply document the plight of tenement dwellers or Dustbowl migrants but sought to reform their subjects’ abominable situations through their pictures.

Image courtesy of Joel Pett

For all of Pett’s bluster, it’s impossible to ignore an abiding humanism that connects him to this progressive tradition. In a single-frame cartoon published just before the 2009 climate change summit in Copenhagen, Pett showed a cantankerous attendee asking, “What if it’s a big hoax and we create a better world for nothing?” while, from the stage, the audience is shown a list of the benefits accruing to environmental remediation, from green jobs and livable cities to healthy children. Pett used that naysayer’s foolishness to make the case for working toward progress so effectively that people around the world have reproduced the cartoon on holiday cards, protest signs, and on the side of a garage in Canada.

When the Pulitzer committee again acknowledged Pett as a finalist in 2011, it was not for his jaundiced view of the world but rather “for provocative cartoons that often tackle controversial Kentucky issues, marked by a simple style and a passion for humanity.”

It’s a folksy description that doesn’t quite fit the enfant terrible I got to know over the weekend. This, after all, is the guy who performed a routine about hooking up male white supremacists with the likes of Kellyanne Conway and Ann Coulter to allay the sexual frustration that undergirds their racial hatred.

He’s got a mean streak a mile wide. But at the end of the day, his enterprise is fueled by hope. “You don’t root for the demise of the republic,” he conceded, “to make your already fun and easy gig funner and easier!”

[Editor’s note: Joel Pett’s work can be seen at Thomas Gallery, 107 N. College, in Bloomington, through September, every Friday from 5 to 8 p.m.]