A year and a half since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on 11 March 2020, life remains radically altered for all sectors of society — for all industries, households, and individuals. While the pandemic has most visibly impacted the most vulnerable populations, it has affected literary arts organizations, and the people who manage them, in unique ways that are, at times, inspirational and uplifting.

Seven local writers and leaders of literary arts organizations spoke to Limestone Post about how they continue to survive the pandemic, and how they have taken their works and organizations in new directions.

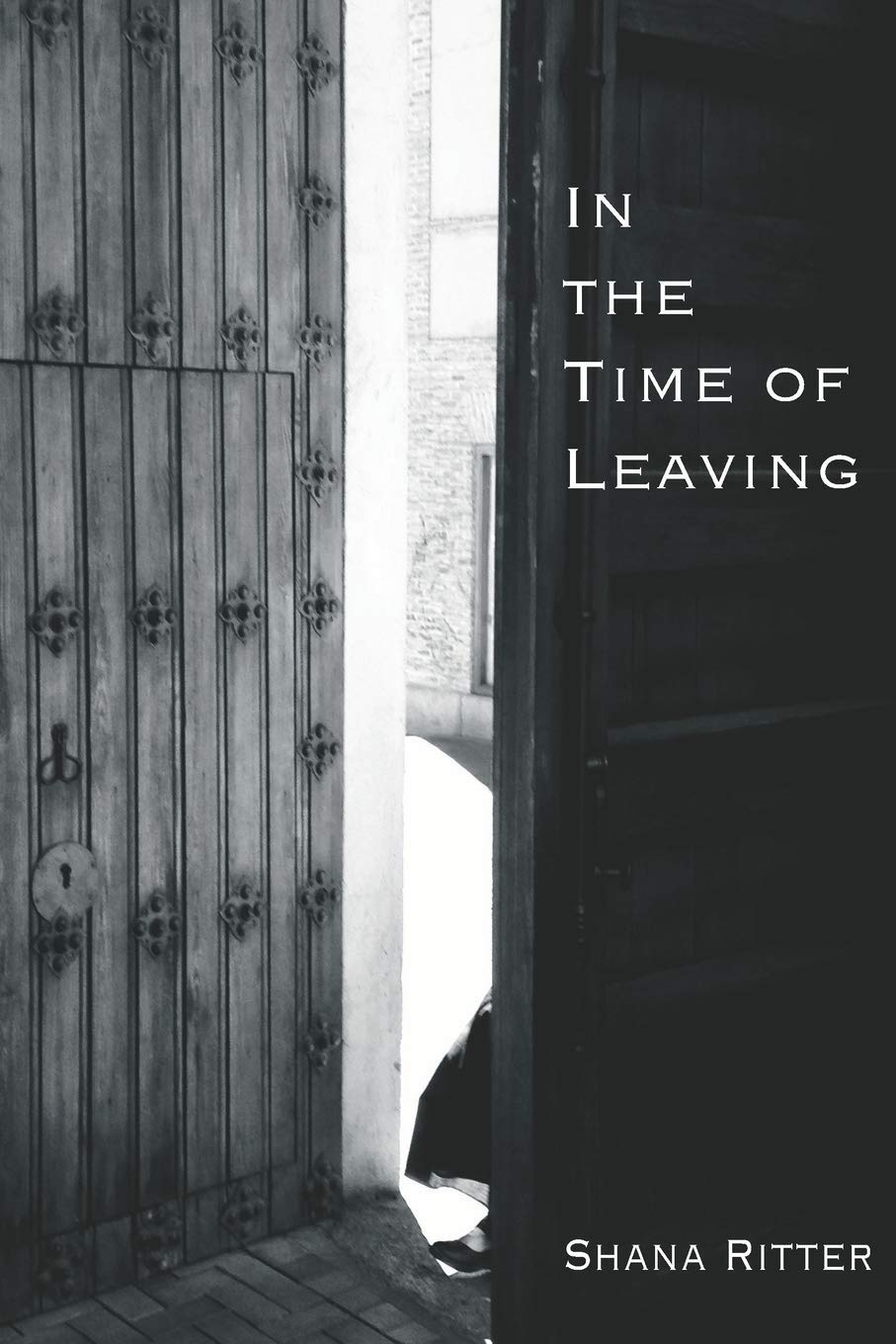

A Pushcart Prize nominee, Shana Ritter has been awarded the Indiana Individual Artist Grant multiple times and has taught poetry and writing workshops in various settings. Her short stories and poems have been published in journals and magazines that include Lilith, Fifth Wednesday, and Georgetown Review. While her mother’s journey as an immigrant in the early 1920s provides the underlying narrative of her most recent poetry chapbook, Stairs of Separation (Finishing Line Press, 2012), her first novel, In the Time of Leaving (independently published, 2019), is a “story of exile and resilience,” set in 1492 during the Inquisition in Spain.

Born and raised in the Bronx, Ritter relocated to Bloomington via Spain, Guatemala, and San Francisco. Since then, Bloomington has become for her the home where she has resided for the longest period. She has been an active traveler, a member of a magazine collective, and a radio show host and has coordinated programs for refugee families and for families that are economically challenged. She has also worked nationally with schools to promote equity, inclusion, and diversity. She has two daughters, four grandchildren, a spouse, and a Bernedoodle named Emmy, their pandemic pup.

End of February 2020: Ritter had just returned to Bloomington from a long weekend in New York City when she had placed In the Time of Leaving at The Jewish Museum bookstore. She had also started to plan promotional readings for spring 2020 and had initiated preliminary research for a new novel that would be set in New York City in the 1600s. Additionally, she had planned a trip to Mexico with her daughter and her daughter’s partner for mid-March, and had been prepared to travel to Spain later that spring.

Within days, she began canceling one trip after another. Then she began to accustom herself to the possibility that she would remain at home for several months. She adopted a puppy and began writing poems about distancing, shelter, and longing for the sea. By May 2020, she realized the several months at home that she had initially foreseen would stretch into many more indefinitely.

Within days, she began canceling one trip after another. Then she began to accustom herself to the possibility that she would remain at home for several months. She adopted a puppy and began writing poems about distancing, shelter, and longing for the sea. By May 2020, she realized the several months at home that she had initially foreseen would stretch into many more indefinitely.

While she says that she has postponed planning for her second novel, she has found herself returning almost exclusively to poetry, her “first voice,” while experimenting with what had been for her a new genre: flash fiction. She also says she could not read longer works for a while. “I wanted things to be short, concise, condensed. I wanted essences,” she says. The pandemic has made her into a “riskier” writer, who, more than ever, wants to “find the core without losing the beauty,” she says. As she continued to write and tune into poetry and prose readings and conversations online, she became increasingly grateful for the virtual worlds that opened up before her eyes — even as the actual physical worlds beyond the trees that border her country home seemed to have shut down.

Although she says that the inability to travel to Spain or to a new destination, as she does each year, “has been a soreness and a longing that there is no way to assuage,” she constantly appreciates the pandemic shelter of her home and the ability to see her grandchildren. “We are the lucky ones,” she says. The post-vaccination, warmer-weather phase of the pandemic, when businesses and recreational venues began to reopen, felt “trickier” for her to navigate. “I am unsure where and when to step out,” she says. Even in the midst of accumulating crises, she vows to keep writing, learning, and facilitating writing workshops, as she hopes that her writing “could give hope, vision, inspiration, refuge.”

For more about Shana Ritter, visit shana-ritter.com

Beth Lodge-Rigal is the founder of Women Writing for (a) Change Bloomington. Now the organization’s outgoing creative director, she has facilitated writing circles and retreats and engaged in outreach and directed programs for the Bloomington writing school. She has also designed and implemented next-generation Conscious Feminine Leadership Training in Cincinnati and Bloomington for women who are eager to learn about new 21st-century leadership paradigms. As she passes the creative directorship torch to Mary Beth O’Brien, she plans to continue specialized facilitation in the upcoming years with Women Writing for (a) Change Bloomington, the organization that she loves so much.

According to Lodge-Rigal, Women Writing for (a) Change was fortunate because all its writing programs could continue virtually starting in spring 2020. She says: “In surprising ways, we found our circles grow as we were suddenly able to welcome folks from farther afield. Places like Oregon and Texas and Colorado.” In summer 2021, WWf(a)C could also open up for a small, in-person writing camp that observed masking, distancing, and hand-washing protocols. The Bloomington school will also offer smaller in-person classes this fall, together with their virtual counterparts.

When asked how the pandemic has affected her as a writer, Lodge-Rigal admits, “I cannot speak for all the writers in our community, but the pandemic has been full of grief, uncertainty, weariness, and isolation. Having an outlet to process the changes in our world(s) has been helpful.” She also says she experienced long periods of inertia as a writer during the first several months of the pandemic’s outbreak. Projects were postponed during this time of “languishing energies,” she says. Other Bloomington community members, including her writer friends, have shared similar observations with her. “We’ve had to postpone live events and are finding ourselves very cautious in our planning for this fall,” she says.

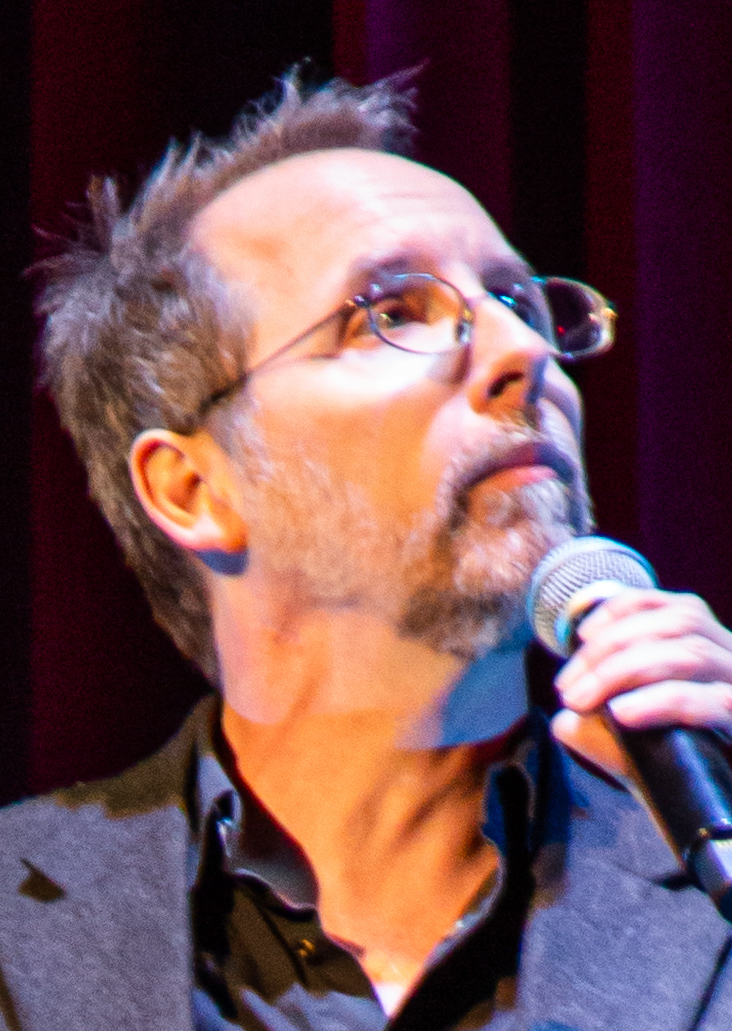

A poet and live sound-effects artist, Tony Brewer is also president of the National Audio Theatre Festivals, treasurer and former head of the Writers Guild at Bloomington, and co-producer of the Guild’s Spoken Word Series with Dr. Joan Hawkins, current head of the Writers Guild at Bloomington and professor of cinema and media studies at Indiana University–Bloomington. Brewer’s latest book is The History of Projectiles (Alien Buddha Press, May 2021).

Brewer says the Writers Guild at Bloomington, like many other arts organizations, had been preparing for a great 2020 year of live performances. But suddenly, the pandemic compelled the nonprofit organization to postpone them indefinitely. The Guild “did practically nothing but wait and see from mid-March till about May [2020], then began doing what we could do online,” Brewer says. Although the Guild is eager to return to putting on in-person shows, he adds, live events remain on hiatus at its regular venues, such as Bear’s Place in Bloomington. Brewer also says the Guild is aware that many of its members cannot attend virtual events due to low bandwidth or other technology-related issues. Consequently, while the Guild’s reach has extended to a certain degree, its local audience has decreased proportionally.

Despite this drawback, the Guild has optimized its online platform to enjoy hosting spoken word performers and musical artists from all across the nation, as well as internationally. Thus, while the Guild could continue to support local artists since the start of the pandemic, it could also showcase some outstanding performers who are based in geographically remote areas relative to Bloomington. Some of these performers include poets David Mura, Eileen Myles, and Ron Whitehead; Irish storyteller Clare Murphy; and musicians Akiko Pavolka, Sam Newsome, and Angelica Sanchez. The Guild could feature them because virtual performances do not require travel and accommodation expenses.

Brewer says the Guild’s financial status remains excellent, however, many thanks to generous support from the Bloomington Arts Commission, the Bloomington Urban Enterprise Association, and the Indiana Arts Commission. He also says that the Guild is thrilled that the reopening of Morgenstern’s Bookstore has enabled it to restart its prose reading series there. However, the Guild’s Spoken Word Series will continue in virtual format until further notice. Brewer says: “We are being very cautious when things appear to be opening back up.”

When asked how the pandemic had affected him as a writer, Brewer says the solitude it had brought on, and that he had loved at first, frequently intensified into lonely isolation. He says: “The fact I wasn’t choosing the solitude was a factor. At first, I couldn’t write or read anything new, and I mostly just alternated [between] following all the terrible news and watching old movies for comfort.” Despite this initial writerly impasse, he continued his usual “30-in-30 in April” (writing one poem per day for the National Poetry Month of April 2020) with the additional feature of recording videos as he wrote these “Rona Poems.”

Although co-producing the Spoken Word Series for the Writers Guild at Bloomington has enabled Brewer to feel socially connected, such online activity also involved the challenge of additional screen time after he had already spent most of his work day at his computer. He says: “I am a relentless live performer (live sound effects for audio theatre as well as spoken word) and being shuttered and then boxed in is a drag. I’ve taken time to reflect — I call it having a Big Think.” Brewer’s “Big Think” inspired him to edit backlogged material and to submit poems for publication. His steady productivity paid off with the publication of The History of Projectiles, a project he had been working on since 2017.

Although co-producing the Spoken Word Series for the Writers Guild at Bloomington has enabled Brewer to feel socially connected, such online activity also involved the challenge of additional screen time after he had already spent most of his work day at his computer. He says: “I am a relentless live performer (live sound effects for audio theatre as well as spoken word) and being shuttered and then boxed in is a drag. I’ve taken time to reflect — I call it having a Big Think.” Brewer’s “Big Think” inspired him to edit backlogged material and to submit poems for publication. His steady productivity paid off with the publication of The History of Projectiles, a project he had been working on since 2017.

“I think I am working more quickly and more openly as a writer now than pre-COVID,” Brewer says. While he has always collaborated with other writers and artists, and while his performances retain improvisational aspects, he is becoming more accustomed to posting videos of readings and images of typed poems online since the start of the pandemic. “Just being more spontaneous about getting the work out there and making those opportunities,” he says. While the content of his writing might not have changed much, he says that he had “definitely dwelt in darkness for some months and wrote from there.” Because he has never been an advocate for “response” poems, he has “tried to keep close and personal” anything related to the pandemic. “That’s how I get to the universal, not the other way around.”

For more about Tony Brewer, visit: tonybrewer71.blogspot.com.

[Editor’s note: Hiromi Yoshida is a diversity consultant for the Writers Guild of Bloomington.]

A candidate for the MFA in fiction at Indiana University–Bloomington, Shreya Fadia is editor-in-chief of Indiana Review. Her fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Black Warrior Review, Cream City Review, and The Florida Review Online. Before enrolling in the MFA program, she practiced law in New York City. She is originally from Mumbai, India.

According to Fadia, Indiana Review transitioned almost entirely to remote operations, like many other organizations, at the pandemic’s start and for much of the past year and a half. Since IR staff were already reading submissions and doing most of their editorial work online, the pandemic led to only “minor procedural changes.” However, the inability to occupy physical office space required the use of technologies like Zoom and Slack for IR staff to continue communicating with each other. Fadia admits: “We were of course fortunate to have been able to transition to remote work so easily, and to even have that option available to us. But remote work also has its downsides.”

A major change for IR editors since the pandemic’s outbreak has been using Zoom to conduct deliberation meetings. Since IR editors are also MFA students in a very small degree program, they have the chance to get to know each other well outside of IR. Before 2020, they held deliberation meetings at the homes of editors on Friday evenings. And so, while the primary purpose of those meetings had been to discuss submissions, they also yielded opportunities to enjoy spending quality time with the MFA colleagues whom they knew and liked. “They felt more like gatherings than meetings, a reprieve,” says Fadia. She laments that Zoom cannot “replicate that very particular experience” — one that involves “discussing a submission while being squeezed into a tiny living room with ten other editors and readers, everyone balancing laptops and plates of food on their laps.”

Although IR staff have begun to return to more in-person work, Fadia says that only after she has completed her term as editor-in-chief will they gather safely again. At the same time, she anticipates continuing Zoom and Slack use, due to the greater flexibility that they both offer.

When asked how the pandemic has affected her as a writer, she replied that she wrote “a lot more” during the first several months of the pandemic’s outbreak than during the months preceding it. “I find I am able to write more productively when I’ve had more time to myself in my own mental and physical space.” After those first several pandemic months, however, her productivity declined “significantly.” She says it is difficult to determine how much of that decrease had been due to the pandemic, or to other circumstances, such as the 2020 U.S. presidential elections, or to ongoing domestic and global crises — or if that decrease had actually been “part of the natural ebb and flow” of her writing process. And so, she feels that it is still too early to specify how she and her work have been affected by the pandemic. After all, the contexts within which to conduct such assessments are ever-fluctuating.

A poet and editor, Rachel Sahaidachny is also executive director of the Indiana Writers Center. As a board member of The R/Evolution Fund, she redresses inequities in arts communities. She holds an MFA in poetry from Butler University and won first prize for the Wabash Watershed Indiana Poetry Awards. Formerly poetry editor of Booth: A Journal, she now serves as associate editor of The Indianapolis Review. While she co-edited Not Like the Rest of Us: An Anthology of Contemporary Indiana Writers (INWords, 2016), her recent writing has appeared in publications such as The South Dakota Review, The Southeast Review, Radar Poetry, Community of Writers Poetry Review, Indiana Humanities, Nuvo, and Red Paint Hill. She has more than fifteen years of nonprofit management experience, and during the past decade, her focus has been on arts administration.

Sahaidachny lives on the east side of Indianapolis. She is married, and has a pandemic puppy, a “sassy” French bulldog, Zelda, named after Zelda Fitzgerald, “empress of the Jazz Age.” She says that although she reads a substantial number of poems and essays, one of her “guilty pleasures” when wanting to decompress or “escape” involves immersion in the supernatural/paranormal fantasy world of fiction, “especially anything with witches.” Her current obsession is The Casquette Girls series by Alys Arden.

When asked about the pandemic’s effect on programming for the Indiana Writers Center, she replied, “When I think back to March 2020 and the beginning of the pandemic, it feels far away.” Even so, she reports that in the midst of numerous shifts and transitions, the IWC managed to continue its programming, while supporting its affiliated writers. IWC staff, teachers, and volunteers “worked diligently to create space for community and sharing,” as IWC partnerships expanded, and new sources of funding were located to support operations. Due to these partnerships and funders, as well as to overall community support, the IWC’s program income did not decrease significantly, and the IWC was guaranteed the required funding to survive the economic downturn that the pandemic has caused for numerous industrial sectors. In fact, the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana Authors Awards honored the IWC with the 2020 Literary Champion title.

According to Sahaidachny, “We [IWC staff] learned a lot about what makes virtual programs successful, and we tried many virtual platforms, including Zoom, Facebook Groups, and YouTube.” Consequently, they could locate former participants of IWC’s in-person programs, who had moved away from Indianapolis, and to invite them to join those programs virtually. The IWC had, in fact, become a resource for writers beyond Indiana. Sahaidachny says the pandemic enabled an expansion that had been achieved in just several months, rather than over the course of several years.

When asked how the pandemic has affected her as a writer, Sahaidachny said that although she has written numerous grant applications to enable IWC survival, she has actually been struggling to manage her own personal writing routines since the pandemic’s outbreak. She senses that this writerly impasse has been exacerbated by the pandemic during ongoing “major transitions” within her family. Specifically, her writing often focuses on mental health complications and mother/daughter tensions. This focus derives from her lifelong struggle to communicate with her own mother, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and other mental health challenges. Since the end of 2020, her mother’s overall health became chronically challenged until her death in September 2021.

Nearly two weeks before her mother’s death, Sahaidachny had said that the craft of writing initiates for her “a process of untying deep emotional knots.” She also said, “I am holding grief and holding it and holding it. And I might not let it out until [my mother] finally transitions. Until it breaks through me.”

For more about Rachel Sahaidachny, visit rachelsahaidachny.com

Professor of English emeritus, Matthew Graham is Indiana Poet Laureate and has taught creative writing for thirty-five years at the University of Southern Indiana. Throughout those years, he served as the Creative Writing Program director; Ropewalk Writers Conference co-director; Southern Indiana Review founding co-editor; and Southern Indiana Visiting Writers Series founder. The author of four books of poetry (New World Architecture; 1946; A World Without End; and The Geography of Home), he has won an Academy of American Poets Award, a Pushcart Prize, a Vermont Center Studio Fellowship, and two Indiana Arts Commission Master Fellowships.

“Although I’m not a native Hoosier,” Graham says, “I’ve lived and worked in Indiana for over thirty-five years. And I say that with real pride.”

Graham says the pandemic led to the cancellation of all his State Poet Laureate travel plans. Although he could use Zoom to judge writing contests, and to teach, or to give talks to high school and college classes, “it has just not been the same as meeting and visiting with people in person,” he says. Nevertheless, he thanks the Indiana Arts Commission for extending his State Poet Laureate term for an additional year, as he hopes that he can hit the road again this fall to realize his goal of visiting every county and arts district in the state of Indiana.

Because his retirement from teaching coincided with the start of the pandemic in 2020, he says both life-changing events forced him to “begin to put a lot of things in perspective.” Although he is uncertain how the pandemic has affected him as a writer, he says that many of his pre-pandemic concerns and worries could be “rather petty.” Consequently, he is focused on optimizing his remaining time to become “a better writer,” and “a decent person.”

Natalie Solmer is an assistant professor of English at Ivy Tech Community College and the founder and editor-in-chief of The Indianapolis Review. Her work has been published in a wide range of literary journals that include North American Review, Pleiades, Willow Springs, Colorado Review, The Literary Review, and Glass.

Solmer grew up in South Bend, Indiana, and attended Clemson University, where she majored in horticulture. Before she earned her MFA in poetry at Butler University, she worked as a grocery store florist for thirteen years.

Because The Indianapolis Review has been an exclusively electronic literary journal since its inception, Solmer says its basic operations have remained unchanged since the pandemic’s outbreak. Although the journal’s entire staff live in Indianapolis, career and family responsibilities prevent them from gathering frequently for in-person meetings. Instead, they use email to comment on submissions, vote on acceptances, and allocate webpage creation projects. They also use social media to promote The Indianapolis Review.

Solmer had started up the online journal knowing that such virtual staff activities would be much more convenient for all.“I couldn’t get out or travel to meet writers and go to events,” she says, “but I could meet people virtually through The Indianapolis Review, and by publishing them.”

Although basic operations for the journal have been unaffected by the pandemic, she says, “[the staff] have all had more stress, so, that can make it harder to accomplish the tasks that we need to.” She also noticed an increase in submissions since the pandemic’s outbreak. She says that the greater number of people who self-isolate within their homes might account for that uptick.

Journal management has enabled Solmer to feel mentally and emotionally connected with other writers throughout the pandemic. She says, however, that although she enjoyed the additional time with her partner and their children, she had been left with less time to devote to her own work. “I was never alone, and often caring for others,” she says. Nevertheless, she remains grateful to have retained her full-time teaching job at Ivy Tech by offering online classes from the safety of her own home.

Her partner, however, did not have the option to work from their home, since he is a cable and internet installation technician. When he returned to work after a hiatus of several months, he was infected with the coronavirus and transmitted it to Solmer and their children.“I just feel lucky that we are all okay and survived,” she says. “That feeling certainly propels me to want to get my book published sometime before I die.” Although she has published numerous poems, like many other poets she remains challenged by the complicated process of placing her full-length poetry book manuscript with a publisher.

She says, however, that she and her partner “got much closer during the pandemic,” and that this closeness had solidified their relationship. This entire experience impacted her writing process. “Several poems and themes in my poetry that I had struggled with for years suddenly became clear for me,” she says. Moreover, when she was experiencing the worst COVID symptoms, she had an extremely vivid visitation dream about her deceased grandmother, to whom she had been very close throughout her childhood years. She would eventually write a poem about this dream.

For more about Natalie Solmer, visit nataliesolmer.com

These writers are notable, not only for their literary achievements, but also for their inner strength and resilience throughout these challenging pandemic times. Their travel plans have been disrupted; their social interactions have become primarily virtual; and they have effectively managed challenging mind states. They write on through the pandemic — through challenges like recovery from COVID, death in the family, isolation and loneliness — ultimately overcoming writer’s block.

“A Conversation With Indiana Poet Laureate, Matthew Graham” by Historic New Harmony

Publisher’s note: This article is the first in a series on how local artists and arts organizations have been affected by the pandemic. It is made possible in part by a grant from the Bloomington Arts Commission, the Bloomington Urban Enterprise Association, and the Zone Arts Grant Program. We thank them for their support!

Publisher’s note: This article is the first in a series on how local artists and arts organizations have been affected by the pandemic. It is made possible in part by a grant from the Bloomington Arts Commission, the Bloomington Urban Enterprise Association, and the Zone Arts Grant Program. We thank them for their support!

You can help support local writers, photographers, illustrators, videographers, and others but donating to Limestone Post. Thank you!