“He told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth.”

—Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

How did the present Supreme Court of the United States get so far out of tune with so many Americans, and what’s to be done? We can trace much of this puzzle to Chief Justice John Marshall, the most venerated jurist in American history — venerated mostly for his opinion in Marbury v. Madison (1803), wherein our Supreme Court declared itself supreme. This is the story behind that opinion.

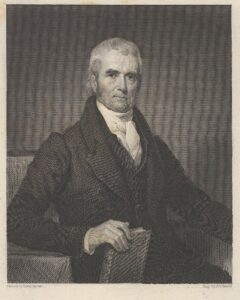

John Marshall was a distant cousin of Thomas Jefferson and served as a staff officer for General George Washington, secretary of state for President John Adams, and chief justice of the United States. | Painting of Marshall by Henry Inman, 1833

A distant cousin of Thomas Jefferson, Marshall served as a staff officer for General George Washington. The cousins detested each other for reasons that remain a matter of easy but unconfirmed speculation. Tall for his day — only one inch shorter than Washington — Marshall was one of the few athletes who could clear his own height in the high jump. Nicknamed “Silverheels” for his athletic prowess, socially he was one of the most clubbable men of his day. His politics were those of a staunch Federalist; during the ratification debates he spoke out as a forceful advocate of the judiciary branch of government. In Federalist President John Adams’ administration, he served first as secretary of state and later as chief justice of the Supreme Court, briefly holding both offices simultaneously.

In the period after President Adams lost his bid for reelection in 1800, it was Marshall’s duty as Adams’ secretary of state to deliver the commission appointing William Marbury as a justice of the peace. However, in Adams’ last-minute scramble to pack judicial vacancies with handpicked appointees, mostly Federalist, a few commissions did not get delivered. Marshall’s brother James, enlisted to help with the deliveries, wrote a note explaining that he would not be able to deliver them all, indicated which ones they were, and left those commissions behind. Marbury’s was one of them.

Next day the new president, Republican Thomas Jefferson, strolled out to visit his State Department. There he found on a table a sheaf of those undelivered commissions. Jefferson thought his new secretary of state, Republican James Madison, was not obliged to deliver them and they were therefore not valid. The commissions were duly set aside. Marbury took exception. With three other appointees in the same boat, Marbury sought to sue Madison for delivery. It was their Supreme Court case that soon became famous as Marbury v. Madison.

Even though Secretary of State John Marshall was responsible for the failure to deliver William Marbury’s commission, he did not recuse himself as chief justice when Marbury’s case was filed with the Supreme Court. | Photo by Pavel Danilyuk

By then the chief justice of the six-person Supreme Court was an Adams appointee. Who? The very same John Marshall who, as Adams’s secretary of state, was responsible for the failure to deliver Marbury’s commission. Did Marshall’s connection with Marbury move Marshall to recuse himself? No. Indeed, he took the lead in the case and wrote the court’s unanimous opinion for the quorum of four justices who were able to attend the trial.

Charles Lee represented Marbury with great skill. Lee had served as attorney general for Federalist presidents George Washington and John Adams. After Marbury, he successfully defended Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase in his impeachment trial and Aaron Burr in his treason trial. Secretary Madison did not attend the Marbury trial, nor did anyone represent him.

Marshall framed the case in terms of three questions. First, does Marbury have a right to the commission he demands? Second, if so, and that right has been violated, does he have a legal remedy? Third, if the law affords him a legal remedy, can this court order it? If the answer to each question is “yes,” we have a declaration of political war between the Supreme Court and the Jefferson administration.

The court sided with Marbury on the first two questions. Yes, the signing of the commission, delivered or not, made it Marbury’s property, which entitled him to a five-year term as justice of the peace. And yes, the laws of the land afforded him a legal remedy. But no, the Supreme Court could not order such a remedy — in legalese, could not issue a mandamus. Why? Because the Constitution created the Supreme Court as an appellate court, and not — with certain specific exceptions — as a court of original jurisdiction, a fact-finding trial court. And this case was not an appeal from a lower court.

Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion in “Marbury v. Madison” declared the U.S. Supreme Court supreme. | Photo by Katrin Bolovtsova

In effect, Marshall ruled against his fellow Federalist because Marbury and his lawyer, the astute Charles Lee, had come to the wrong court. They had come to a court of appeals, not a court that could make original findings of fact — although there were constitutional exceptions to that rule, and some of the court’s questioning did seem to delve into the facts of the matter.

So why had Marbury come there under the expert guidance of a lawyer as able as Charles Lee? The reason was an act of Congress in 1789 that seemed to make this particular kind of dispute an exception to the court’s usual role as a strictly appellate court. But Marshall ruled that Congress had no constitutional power to pass such legislation, to extend the judicial range of the court as laid down by the Constitution. And Marshall quoted the Constitution to that effect.

This ruling left lawyers ecstatic, because it placed the judicial branch of government — previously the pitiable sapless branch that didn’t even have a proper place to meet — above Congress, heretofore the august dominant branch. Hence the notion that Marbury v. Madison is the ruling wherein the Supreme Court declared itself supreme.

The ruling in “Marbury v. Madison” left lawyers ecstatic, because it placed the judicial branch of government above Congress. | Photo of the Supreme Court Building by Leandro Paes Leme

And there it sits in our National Archives among such other hallowed documents as the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights: Marbury v. Madison, 1803, tagged as the constitutional cornerstone wherein the Supreme Court first declared an act of Congress to be unconstitutional.

But like many hallowed hallmarks, Marshall’s creation merits serious criticism. And President Jefferson did file Marbury among what he called cousin John Marshall’s “twistifications” by ordering that it never be cited by anyone in the Jefferson administration.

First criticism: In today’s judicial environment, Marshall would have faced immense pressure to recuse himself for his personal role in the botched delivery of Marbury’s commission. Possible excuse #1: Marshall knew that he could hardly be condemned for a ruling against his fellow Federalist. Possible excuse #2: In Marshall’s time, recusals were reserved mostly for situations in which the judge might derive illicit gain from a ruling. Here no such gain was in play.

Thomas Jefferson and his distant cousin John Marshall allegedly despised each other. Marshall was chief justice of the United States when Jefferson became president; Jefferson called the ruling in “Marbury” one of Marshall’s “twistifications.” | Painting of Jefferson by John Trumbull

Second criticism: Marshall misquoted Article 3, the part of the Constitution that supposedly denied Congress the power to enact in 1789 the legislation that let the court treat Marbury’s case as an exception to the court’s usual role as a strictly appellate court. To appreciate this point, we must compare what Marshall wrote in his ruling with what Article 3 actually says in its exceptions clause.

Marshall: “The Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction in all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be a party. In all other cases, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction.”

The Constitution, Article 3, Section 2: “In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.” (Italics added.)

It seems, then, that the exceptions clause of the Constitution actually gives Congress the very power that Marshall denies in his version of Article 3.

Why did Marshall edit Article 3 as he did, if not to grant the federal judiciary the power he thought it deserved, with or without constitutional approbation? One may wonder whether Marshall’s edit escaped the notice of Charles Lee and other critics prepared to assume, reasonably enough, that Marshall would quote the Constitution correctly.

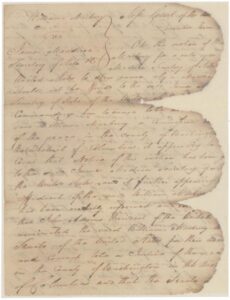

Show-cause order served on James Madison, Secretary of State, 1802; Records of the Supreme Court of the United States; Record Group 267; National Archives. The document shows damage from the 1898 fire in the Capitol Building. | Source: NationalArchives.gov

Third criticism: Did Marshall soon utter a remorseful cheer for legislative checks and balances? In 1804, the year after Marbury, the U.S. House of Representatives impeached one of Marshall’s Supreme Court colleagues, Samuel Chase, for alleged bias on the bench. On January 23, 1805, the Senate impeachment trial was still in progress (Vice President Aaron Burr presiding). On that day, Marshall wrote a sympathetic letter to Chase, in which he said, “The present doctrine seems to be that a Judge giving a legal opinion contrary to the will of the legislature is liable to impeachment.” He added that “If the legislature did not agree with a Judge’s holding, they should reverse it by statute.” He continued: “I think the modern doctrine of impeachment should yield to an appellate jurisdiction in the legislature. A reversal of those legal opinions deemed unsound by the legislature would certainly better comport with the mildness of our character than a removal of the Judge who had rendered them unknowing of his fault.” In other words, Marshall admits here the nation’s need for a better legislative check on Supreme Court rulings than the clumsy resort to impeachment.

Given its numerous flaws and Marshall’s second thoughts, might we treat Marbury v. Madison as reversible error? The pros and cons could motivate a lively moot court drama in any law school. The ruling’s error seems plain enough, but is the ruling too entrenched to be reversible?

Entrenched or not, a fuller understanding of Marbury v. Madison may help both the American judiciary and the American public to grow more sympathetic to notions of judicial reform. Marshall’s own suggestion of some sort of legislative check and balance on Supreme Court rulings might merit further development. Given the unpopularity of recent court rulings in women’s rights, voting rights, and the merchandising of elections disguised as free speech, the time seems ripe. Congressional control of the court’s purse strings and congressional ability to initiate impeachment proceedings have plainly not sufficed to put the court more in tune with the public. A step in the right direction might be, as some judicial scholars suggest, a constitutional amendment limiting terms on the Supreme Court to fifteen years.

Recent articles about today’s Supreme Court

“5 reasons Supreme Court ethics questions are more common now than in the past,” by Charles Gardner Geyh, Distinguished Professor and John F. Kimberling Professor of Law, Maurer School of Law, Indiana University. The Conversation.

“7 in 10 Americans think Supreme Court justices put ideology over impartiality: AP-NORC poll,” by Thomas Beaumont and Linley Sander. The Associate Press.

“Presidential immunity extends to some official acts, Supreme Court rules in Trump case,” by Ashley Murray and Jacob Fischler. Indiana Capital Chronicle.

“US Supreme Court curbs federal agency powers, overturning 1984 precedent,” by John Kruzel and Andrew Chung. Reuters.

“Loss of Supreme Court legitimacy can lead to political violence,” by Matthew Hall, Professor of Constitutional Studies, Political Science and Law, University of Notre Dame; and Joseph Daniel Ura, Professor of Political Science and Chair of the Department of Political Science, Clemson University. The Conversation.

Commentary

“This Is Why the Supreme Court Shouldn’t Try to Do the EPA’s Job,” by Kate Aronoff. The New Republic.

“A SCOTUS ruling on laughing gas abandons precedent for the absurd and the partisan,” by Michael Leppert. Indiana Capital Chronicle.

“The Supreme Court’s Latest Power Grab: Regulatory Oversight,” by Shawn Musgrave.The Intercept.