Indiana has been home to strategic forts and military bases since long before the American Revolution (as in Fort Knox in Vincennes and Fort Wayne in the northern part of the state). The landlocked state even has an important naval base at Crane in Martin County. And for a brief period in the 1940s, a sprawling U.S. airbase occupied the farm fields near Seymour. Near the end of World War II, in April 1945, a group of African American pilots attempted to enter the all-white officers’ club at the Freeman Army Airfield. It has been argued that the protest guided by lieutenants Coleman A. Young and Roger “Bill” Terry would later play a role in President Harry S. Truman’s firm and explicit desegregation of America’s Armed Forces in 1948.

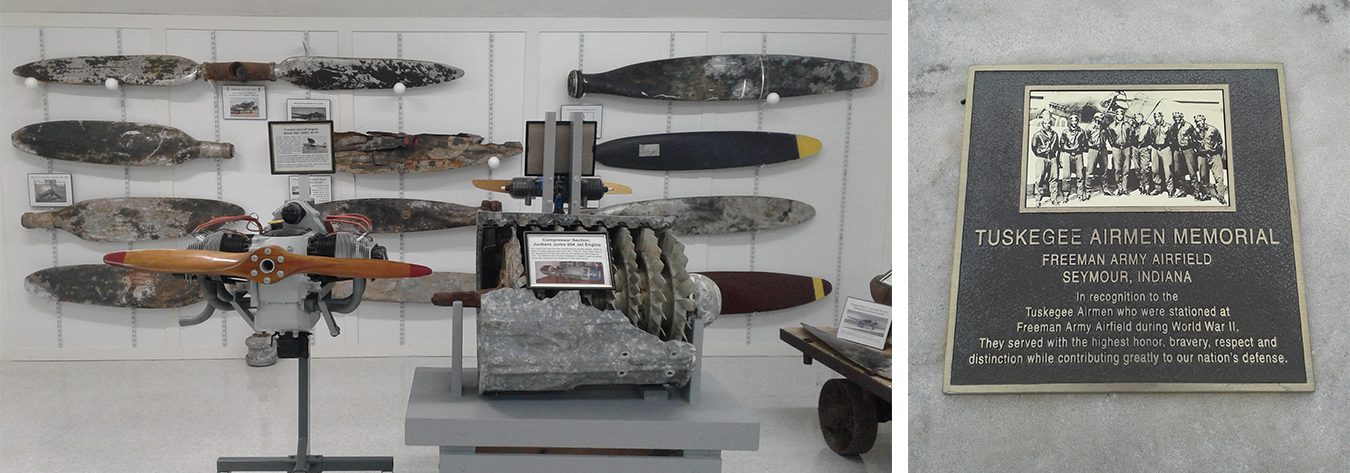

The U.S. Army built Freeman Army Airfield in 1942 on thousands of acres outside of the city, where it served multiple roles — predominately as a training facility for pilots using multiengine aircraft — before being returned to the city in 1947. The Army repurposed the base as the Foreign Aircraft Evaluation Center in 1945, and, soon, enemy aircraft that had been captured during World War II began arriving at the facility to be disassembled and studied by American engineers. These machines included some of the most advanced technology the world had ever seen: German jets, V-1 buzz bombs, and V-2 rockets. As the program concluded, many of the aircraft were shipped to larger bases and museums across the nation, though in 2009 it was discovered that the Army had buried a cache of parts in the surrounding fields. However, Freeman Airfield had a bigger role to play in American history.

(left) Parts of WWII aircraft that had been brought to Freeman Airfield to be studied. (right) A memorial plaque honoring the Tuskegee Airmen at the site of the Freeman Army Airfield in Seymour. | Photos by Paul Bean

Black soldiers fought with distinction and defended their nation in WWII in all occupations and theaters of war, but they returned home to Jim Crow America and remained inferior in the eyes of many Americans. This was so despite a report sent to President Truman’s chief of staff in August 1945, in which General Joseph McNarney said that in introducing black soldiers into combat, “there would have been no measurable loss in combat efficiency” of Army units. A survey conducted in the same year among white officers indicates a similar response, with 77 percent of participants reportedly gaining respect for their black comrades after their introduction.

However, McNarney admitted that experimenting with desegregation of the Armed Forces on the homefront would produce a myriad of difficulties “of a social nature … on the part of politicians, the local communities involved, the leaders of Negro opinion, including the Negro press. Any one of these groups can cause so much comment and racial friction as to make the entire experiment a failure.”

An official U.S. Army Air Forces photo of Colonel Robert R. Selway Jr. (center) reviewing the 618th Bomber Squadron, which is part of the 477th, at the Atterbury Army Air Field in Indiana on June 24, 1944. The Tuskegee Airman that Colonel Selway is facing is Hubert L. Jones. Selway would later segregate the officers’s club by designating all black officers as trainees. | Public domain

The 477th Bombardment Group was an African American unit assembled around a core group of vaunted Tuskegee Airmen that began arriving at Freeman in March 1945. The men were met with blatant racial prejudice from both the people of Seymour and white service members on the base, including open racism displayed by Robert Selway, their commanding officer. Selway ordered the black officers to be designated as trainees, subordinate to their white instructors, in order to illegally circumnavigate Army regulation AR 210-10 that stated no officers’ club may be operated unless all officers were permitted entry.

When black officers attempted to enter the all-white “instructors” club in protest of Selway’s prejudice, their actions became known as the “Freeman Airfield Uprising” or the “Freeman Airfield Mutiny.” However, using the words “uprising” and “mutiny” imply a violent altercation that does not accurately describe what was a peaceful, nonviolent protest. Jim Allison, an IU Professor Emeritus, says that the “mutiny” at Freeman Airfield can be considered one of the earliest examples “of the orderly, lawful civil rights protests that we tend to identify with the later era of the Montgomery bus boycott, the lunch counter sit-ins, and MLK.”

On the evenings of April 5 and 6, groups of black officers approached the club, demanded entry, and were subsequently arrested by the armed white officer barring the door. The protesting officers argued that they possessed equal rights to white officers and simply wanted that to be respected. Instead, they were met with staunch racism, disrespect, humiliation. And despite it being a part of the greater movement spreading through the American military, their protest, for whatever reason, was not included in McNarney’s report just a few months later. Allison says, “I often wonder if it would have made more of a splash, and won its proper place in history, had it not been overshadowed, with everything else, by the monumental death of President Franklin Roosevelt a few days later, on April 12.”

Pilots and ground officers of the 477th with one of their B-25 bombers. | Public domain

Indeed, Freeman was not the first place the men of the 477th had been involved in protest of the deeply engrained racism perpetuated by the command structure of the Army. Prior to Freeman, the 477th was stationed at Selfridge Airfield near Detroit, the scene of violent race riots in 1943. Detroit was a hotbed of unrest, and the desire for justice and equality found in civilian protesters was also held by the pilots stationed at Selfridge. Though not directly affiliated with the 477th, a group of black officers at Selfridge attempted to enter a white officers’ club.

In 1945, when the black men of the 477th at Freeman used the same means of protest to expose the thinly veiled segregation within the Army Air Corps, 101 officers were arrested for disobeying Selway’s orders that barred them from the instructors club, a charge that carried the threat of death. Their actions were neither aggressive nor belligerent, a far cry from the violence associated with the lingering title as a “mutiny.” Nonetheless, they were treated as violent usurpers and rebels. Similar scenes would play out across the South during the height of the Civil Rights Movement a few years later. In the wake of the ensuing public relations disaster, most charges were dropped, though many of the men would carry on their records official “reprimands” for insubordination. One of the arrested men, Lt. Quentin P. Smith, called Selway’s order a “Jim Crow regulation” and, in a document endorsed by him, expressed his “unshakeable belief that racial bias is Fascistic, un-American, and directly contrary to the ideas for which he is willing to fight and die.” His rebuke speaks to the growing outrage among black servicemen.

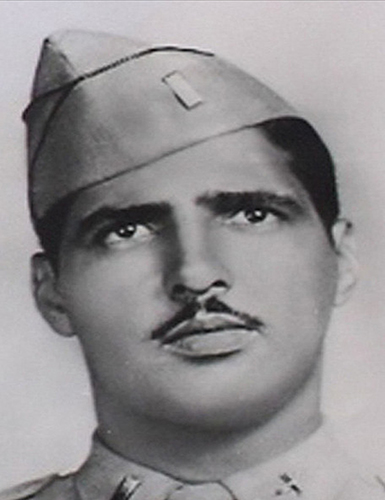

Lt. Roger “Bill” Terry was demoted, fined, and dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Army Air Corps in the 1940s for protesting an injustice. | Photo courtesy of the personal collection of Roger Terry (CC BY 2.0)

Three officers, Lt. Roger “Bill” Terry among them, were charged with “jostling an officer” and court-martialed. They were singled out and made examples of the consequences faced by black men who stood up to injustice. However, only Lt. Terry was officially charged, demoted, fined $150, and dishonorably discharged, losing his right to vote. The other two officers were acquitted. It was not until the 1990s that the Air Force began removing the charges from the involved officers’ records, but only if they requested it. “I was fortunate to meet Bill Terry and other Tuskegee Airmen at their 1997 reunion in Seymour,” Allison says. “At the end of one of their sessions, my wife and I saw Bill trying to mollify a fellow airman who simply refused to calm down. It was quite a ruckus. We happened to encounter the fellow as we were leaving the field, and I asked him why he was so upset. He explained: The Air Force had put a blemish, unfairly, on every one of those men’s records, but would now remove each blemish only upon individual request. What an insult! The Air Force should purify each of those records on its own initiative. Why should the injured party have to request redress of an injury inflicted unjustly by the Air Force?”

The 477th Bombardment Group made history by speaking up in an America that was far from open to conversations about equality, adding their voices to the growing chorus of protests urging President Truman to formally ban segregation in the armed forces in 1948.

An industrial park now occupies much of the farmland where Freeman Army Airfield stood. The only reminders of its story remain in a museum housed in some of the remaining original buildings, a small monument to the Tuskegee Airmen resting beneath an American flag, and the two original airstrips now cracked and sprouting weeds.