Over the past seven years, David Rupp of IndiGo Birding Nature Tours has led birding tours in southern Indiana and Central America. He’s seen thousands of birds, and yet, like every birder, he is looking for those birds that he has never seen. When Rupp witnessed the migration of American white pelican to Indiana several years ago, he was surprised. “I didn’t think that I would see these birds on a regular basis,” he said. And yet now he does. Hundreds of them now populate the state at Eagle Creek Park in Marion County, Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area in Greene County, and other counties during migration. Though they like inland lakes and rivers, they don’t reside here. They are just stopping over then moving on. But for Rupp, just watching their social and feeding behaviors is a marvel. “They are the Harley riders of the sky!” says Rupp.

David Rupp runs IndiGo Birding Nature Tours and has led popular birdwatching excursions in southern Indiana and Central America. | Courtesy photo

Spring is the peak migration period for birds. While seeing American white pelicans, sandhill cranes, snow geese, and others in Indiana is no longer unusual, they reflect the changing nature of bird migration throughout the United States and globally. Ornithologists and birding enthusiasts are witnessing considerable variations in how migration is shaping the lives of birds. But they didn’t always focus on migration. Initially, they concentrated only on a bird’s breeding season.

What was once is no longer

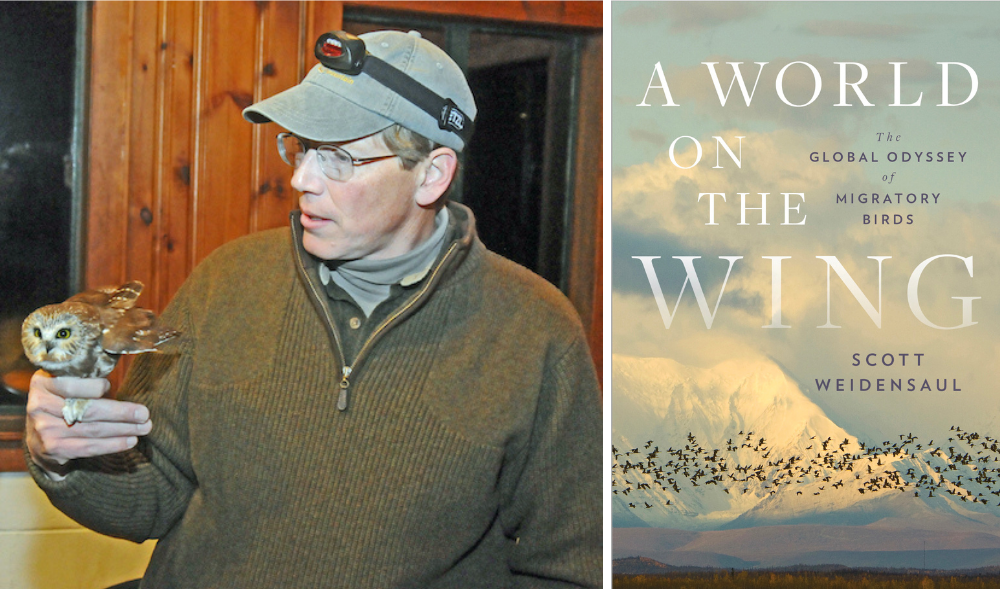

Author of the New York Times best-selling book A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds, Scott Weidensaul has been an avid birder since he was 12 years old. He’s also a citizen researcher, bird bander, and founder of the Project Owlnet, a resource for owl-migration researchers. According to Weidensaul, ornithology as science started primarily in the Northern Hemisphere and Europe on the theory that it was much easier to study a bird that was closer to you than not.

Scientists studied birds during breeding seasons because they were essentially in their backyards. Think about it. Following a bird and figuring out its routes during migration would have required the skills of Superman. Plus, forget about tracking small birds like warblers. The technology wasn’t there, and radio transmitters were too bulky for small birds and often too big for raptors.

What studying breeding couldn’t tell us, though, that we now are learning, is that long-distance migration is the most dangerous part of a bird’s life. Birds face several hazards along the way. Plus, thousands of birds migrate at night, increasing the danger. Confronted with light pollution from cities, bird migrants become disoriented, leading to collisions with buildings, automobiles, and energy installations like wind turbines. Cats, too, are a hazard to migratory birds.

An avid birder since he was 12 years old, Scott Weidensaul is a citizen researcher, bird bander, and founder of the Project Owlnet. He also wrote the New York Times best-selling book ‘A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds.’ | Courtesy photo and image

One massive wake-up call that helped to spur research and technological improvements was the study Decline of the North American Avifauna, published in 2019. The study reports that since the 1970s, our continent has seen the destruction of more than 3 billion birds, nearly 30 percent of approximately 18,000 species of birds worldwide. Using data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey, the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, and the International Shorebird Survey, the study found that (1) waterfowls and raptors are thriving because of habitat restoration, (2) grassland birds like meadowlarks and bobolinks have declined 53 percent since the 1970s, a loss of 700 million adult birds in the 31 species studied, (3) shorebirds such as sanderlings and plovers have decreased by one-third, and (4) 19 species of common songbirds like New World sparrows, New World warblers, and New World blackbirds have lost more than 50 million birds since the 1970s, a particularly hard hit since, in many ways, the loss of common bird species reflects how massive the problem is.

Seeing a species loss and those exceptionally high numbers is hard to recognize because loss is a gradual progression. You constantly suffer from a shifting baseline, says Weidensaul. “It happens over the course of years and decades, and each time there is a slide down, you get used to it.”

Why are we losing so many birds? Why does it matter? Sure, everyone loves the sound of birdsong. There is nothing prettier than the song of a cardinal singing in the morning. We marvel at their murmuration when vast flocks of starlings move in synchronized swirls across the sky. But what most people don’t recognize is the critical economics and ecology of birds.

More than 47 million people spend time watching birds, 41 million of whom are backyard birders. They spend their money on birds, too — approximately 9.3 billion U.S. dollars per year, through bird-related activities in the U.S. From using high-res cameras and binoculars to purchasing bird seed in bulk, birding is a big business.

Plus, as Rupp can testify, ecotourism, too, is big business, with 16 million birding tourists traveling away from home to view birds and spending more than $39 billion for trip-related expenses, equipment, and other expenses, according to a 2016 survey by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

As predictors, birds not only signal what may happen with changes in climate, but they also provide numerous benefits to our environment by keeping our ecosystems viable through seed dispersal and pollination. In fact, some migratory birds like the common redstart — by transporting seeds in their feathers or digestive tract — may help create new habitats, sometimes by dispersing them over more than 300 kilometers. In a 2018 study, scientists found that birds around the world consume 400 to 500 million tons of insects annually. They also scavenge the dead from our roads, our forests, and other places.

Until a few years ago, birders rarely saw American white pelicans in Indiana. Now they’re regular visitors to several locations along their migration routes. These stopped over at Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area in Greene County in April. | Limestone Post

Over their lifetimes, vultures, which have highly corrosive stomach acids, provide the equivalent of approximately $11,600 of waste disposal services per bird. In India, vulture die-offs became a serious crisis. When vultures began to die after consuming the carcasses of dead cattle who had ingested a drug poisonous to vultures, feral dogs took their place as scavengers. Because the sudden increase in rabid dogs coincided with the decrease of vultures, scientists believe that the number of rabies cases increased, estimating that the decline contributed to approximatively 50,000 human deaths from 1992 to 2006.

Birds keep coral reefs viable when seagulls drop layers of guano, which is full of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients. It then filters out to the oceans and fertilizes coral reefs, helping to increase their growth rates up to four times faster. And, finally, birds help clean forests and other areas of harmful insects that prey on trees and other vegetation. For instance, western bluebirds devour insects that spread bacteria in Napa Valley vineyards.

Bird banding

One of the oldest identification methods still used today is bird banding. In 1803, James Audubon used a silver thread tied around the legs of eastern phoebes and was able to track their return to Pennsylvania in 1804. Both he and his future bride, Lucy Bakewell, often watched these birds during John and Lucy’s courtship. Today, bird banding provides a method of identifying birds without recapturing them time and time again. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, more than 64 million birds have been banded.

The Indiana Audubon Society, the second oldest Audubon Society in the nation (founded in 1898), and the Sassafras Audubon Society for southern Indiana currently track the ruby-throated hummingbird and the northern saw-whet owl. Sassafras has been banding northern saw-whet owls since 2002. At Indiana University’s Environmental Resilience Institute’s Kent Farm Research Station, they band dark-eyed juncos, American robins, and other birds. Since 2020, they have banded more than 1,000 birds of around 40 different species. Even the state of Indiana has a banding program for peregrine falcons and loggerhead shrikes.

Brad Bumgardner, executive director of the Indiana Audubon Society, says his organization documents the annual migration of the saw-whet owl and shares their data with other groups, such as Weidensaul’s Project Owlnet. | Courtesy photo

“We study the saw-whet owl, which has a common migration in Indiana in the fall,” says Brad Bumgardner, executive director of the Indiana Audubon Society. “It is a highly sought-after bird. Birdwatchers who may spend their entire life searching to find one in the field may not realize how common they are.” Their program documents migration and fluctuation in migration annually in Indiana and shares it with a network of multiple sites such as Weidensaul’s Project Owlnet.

Miniaturized tracking technology

In the late 1980s, Weidensaul was part of a research team banding and tracking red-tail hawks. He and the team put radio transmitters on their tails, which was the only way to track them across a distance. They used chase teams in vehicles with handheld receivers relaying sightings and projecting destinations to trail the birds. Much like tornado chasers, they used their cars to follow the birds. Sometimes, too, they used small-engine airplanes for tracking. “It was the most time-consuming and labor-intensive approach you could take,” says Weidensaul. “But it was the only way you could do it.” All that has changed with technology.

Researchers are now using bird banding with an electronic microchip called a Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tag, radio telemetry, light-level geolocators (some as small as 2 to 3 grams), or satellite telemetry using GPS location data. “It has opened so much that we didn’t know before, and it has also shown us where the gaping holes are in our understanding [of birds] and the dramatic threats,” says Weidensaul. With technology, ornithologists can now study the whole bird, how they breed, when and where they migrate, where they stop over during migration, and the many impacts they meet along the way. For many researchers, it is about the bird’s lifespan, not just a single part of it.

Funded by the Indiana University Grand Challenges initiative, research by IU’s Alex Jahn focuses on the American robin, a rarely studied backyard bird. For him, birds are sentinels. They can predict what is happening to our ecosystem. Robins, like other birds, he says, can be “barometers of change, a species indicator to understand how changes are impacting the greater ecosystem.” So we need these birds to help us diagnose the impact of weather changes, food, habitat loss, and even disease onset that comes with climate change. We also need birds to show that it is possible to adapt to these changes.

IU’s Alex Jahn, pictured here with an American robin, says birds can be ‘barometers of change, a species indicator to understand how changes are impacting the greater ecosystem.’ | Courtesy photo

“American robins … are made up of over eighty species and are found on all continents except Antarctica,” says Jahn. “We are studying robins in other continents to give us the greater context here in Indiana.”

In their study First tracking of individual American Robins (2019), Jahn’s team tracked seven robins from Denali National Park and Preserve, Alaska, that overwintered in Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Montana. Another robin was captured in Amherst, Massachusetts, and overwintered in South Carolina on its way to Florida. Two other birds were captured in Washington, DC, and ventured only six kilometers from their original capture site. The study found that the existence of substantial variation in the timing and distance of fall migration suggests that robins faced pressure that essentially dictated their migration movements. As a result, Jahn says, robins could serve as “sentinels of environmental change on a continental scale”; their movement or lack thereof might be able to tell us where the climate is influencing migration patterns.

For those birds migrating to Alaska, Jahn examined the type of cues they relied on to adapt and mold their movements in migration. Consider this as if you were a bird. Alaska is more than 3,000 miles from Indiana and on a different latitude. Along the way, climate and terrain dramatically vary. Stopovers, too, depend on the availability of food sources. An Indiana robin has no way of anticipating what to expect along that migration route, let alone know what to expect when they arrive in Alaska.

So, Jahn wants to know, are they using climate, temperature, and rainfall as cues for migration to this different latitude? Did the robins who stayed during the winter in Washington, DC, or Bloomington, Indiana, instead of migrating, stay because of these changes? “What best predicts the migration of a bird to Alaska versus a bird who overwinters in Texas and comes back to Indiana?” asks Jahn. “If we can characterize the cues that they are using to migrate to different latitudes, then we can get a better handle on how migratory birds, in general, can cope with climate change.”

A more recent study (2020), Behavioral responses to spring snow conditions contribute to a long-term shift in migration phenology of American robins, conducted by the Earth Institute at Columbia University, may shed some light on these questions. The study concluded that robin migration was kicking off twelve days earlier than in 1994.

Jahn’s research attempts to answer if robins use climate, temperature, and rainfall as cues for migration to different latitudes. | Courtesy photo

By looking at individual flight paths using GPS backpacks, a unit that weighs less than a 5-cent piece, the study’s authors found that robins started heading north earlier when winters were warm and dry. When weather conditions in their path were snowy, it caused them to adapt their flight schedules along the way. Why is this information critical? Migration timing often dictates mating and breeding seasons. Anything that stands in the way of migration ultimately influences their breeding season and perhaps the ultimate existence of a bird.

Technology, says Jahn, makes it possible to study the common bird’s annual migration cycle and why it may migrate or not. So now we can measure how far the losses go or how birds are adapting and changing migration because of environmental pressures. But we can also use this information to tailor-make conservation dollars and efforts pinpointing where the need is warranted the most.

“It has been tremendously exciting to see and learn about the lives of individual birds by using these new tracking technologies, which in some cases are so small that you can put them on hummingbirds,” says Weidensaul. “It feels like the golden age of migration research. We are just learning so much — it’s like drinking from a fire hose.”

Monitoring birds through technology tells us how birds migrate, but it also reveals the pitfalls, limitations, and liabilities of migration. Physiological changes, too, may result from migration and even why or if a bird migrates. Imagine, says Weidensaul, the bird that you see in the middle of the Pacific Ocean today may have been 15,000 miles away a couple of weeks ago.

Presently, a project two decades in the making is coming to fruition. The International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space project, or ICARUS, uses miniaturized tracking technology that relies on solar energy. Each tag collects data on the bird’s or animal’s position, physiology, and microclimate. The information is transmitted to a receiver on the International Space Station and handled by an electronic data-processing module. The data is then forwarded to a Moscow control center and redistributed to researchers for use. The advantage of ICARUS is tracking collective movements of creatures throughout a lifetime, no matter where they roam. With this additional step, scientists can now see how species adapt to habitat loss, fluctuations in climate, and their responses to these variations.

Radio telemetry tracking

Now that researchers have miniaturized technology, it is not enough just to create the data. It must be collected, archived, and then shared with researchers. That is what Motus Wildlife Tracking System, an international collaborative research network, now does. Currently, 1,073 Motus receiver stations (a number that regularly changes due to towers added or taken offline) exist. Motus uses this network of radio-telemetry towers operating on a radio frequency to track small animals, including bird movements. If a bird comes within the detection range of a tower (up to 15 kilometers depending on the location of the tower’s antennae), the tower reads the device in real time. That data is then centralized at Birds Canada, filtered, analyzed, archived, and disseminated to researchers worldwide. Motus maps let scientists find out where birds go, how fast they go between tracking towers, and how long they stop over.

Allison Byrd, of the IU Environmental Resilience Institute, coordinates the Motus towers for IU. For her, the key benefit is that the Motus towers are local. “For a long time, you could do studies on the wintering or breeding ground,” says Byrd. “But once they left, you couldn’t detect them anymore.” Now Motus is a tool for detecting beyond those limitations. “We’ve realized that there are threats with migration, so there is a push for research on the full cycle of birds so you have a sense of what the migrating birds are encountering.”

Allison Byrd, a research assistant in the Indiana University Environmental Resilience Institute, checks the Motus Wildlife Tracking System on a tower at T.C. Steel State Historic Site near Nashville, Indiana, in 2019. More than 1,000 Motus radio-telemetry towers in 31 countries track small animals, including birds. The data is disseminated to researchers worldwide. | Courtesy photo

In September 2020, Byrd identified two Swainson thrushes that had been tagged in British Columbia just before they migrated last fall. They later detected the same Swainson thrushes as they passed by the Morgan-Monroe State Foresttower. Later still, a Motus tower detected one of those birds approaching Florida. That bird flew a distance of about 2,700 miles. “To think that we are just sitting here in Indiana and, at some point in the night, these birds are making their way [to] really far distances makes it more real,” says Byrd. “To know that that bird was detected with its tiny tag is awe-inspiring.”

Right now in Indiana, seven to eight Motus tracking stations operate at Morgan-Monroe State Forest, Kent Farms and T.C. Steele State Historic Site a few miles east of Bloomington, Mary Gray Bird Sanctuary near Connersville, and four towers operated by the Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo.

Two additional towers are proposed at Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area and the Indiana Dunes National Park, where, Brad Bumgardner says, they hope to track eastern whip-poor-wills that have an outpost population in the Black Oaks Savannah at the Indiana Dunes.

![Allisyn-Marie Gillet, an ornithologist with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, holds a recently banded peregrine falcon chick. ‘The installation of the [Motus] towers is important because they are a function of researchers doing work on migratory species like birds and bats,’ Gillet says. | Photo by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources](https://limestonepostmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Allisyn-Marie-Gillet-IN-DNR_falcon_chick_2017.05.03_Petersburg.jpg)

Allisyn-Marie Gillet, an ornithologist with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, holds a recently banded peregrine falcon chick. ‘The installation of the [Motus] towers is important because they are a function of researchers doing work on migratory species like birds and bats,’ Gillet says. | Photo by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources

“The installation of the towers is important because they are a function of researchers doing work on migratory species like birds and bats,” says Allisyn-Marie Gillet, an ornithologist with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources. “We collect data, and then it is all submitted to the Motus network where it can then be shared with a collective of researchers in the network.”

Radar tracking and forecasting

With the inclusion of radar technology and two decades of accumulated data, scientists can now forecast migration times as a way to plan for and prevent adverse migration events like bird collisions. First widely employed by the British during World War II, radar has since been used to study birds. Now scientists are using it to track migration on a continental scale.

In the 1990s, Doppler radar progressed to Next-Generation Radar (NEXRAD), becoming operational for ornithologists to examine migration patterns. At first, parsing the massive datasets was extremely difficult, but now with machine learning, cloud-based computing and power, and advances in data science, it has progressed rapidly. In 2012, BirdCastwas created and featured real-time migration maps. Scientists could finally track and follow migration via BirdCast, a collaboration between Cornell Lab of Ornithology, University of Massachusetts, and Colorado State University. It also led to a new discipline of radar ornithology.

After BirdCast came the 2019 creation of MistNet. A 2019 Science article, “Using artificial intelligence to track birds’ dark-of-night migrations,” describes the creation of MistNet. Cornell Lab and the University of Massachusetts employed artificial intelligence and NEXRAD data to sort through the National Weather Service’s two decades of accumulated images and data. Using artificial intelligence, MistNet distinguished radar information about birds, bats, and insects from other radar images. MistNet can identify at least 95 percent of all biomass. Not only does MistNet help scientists use existing weather-radar data, but it also boils down sizable new datasets generated by citizen-science projects such as eBird of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Because migration forecasting can now be pinpointed to days and months, cities all across the U.S. can create conservation efforts to help birds during migration. For example, Texas cities like Austin, Dallas, Houston, and Fort Worth are now dimming or shutting off their lights in a move initiated by the National Audubon Society’s Lights Out program. Why? During peak migration times, light pollution disrupts and disorients birds from their flight paths. Currently, Indianapolis has a Light’s Out program. An initiative of the Amos Butler Audubon Society in central Indiana, the Indianapolis program is done in collaboration with the City of Indianapolis and its building managers. In Bloomington, some people have express an interest in establishing a Light’s Out program, but none has been created to date.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources is working in conjunction with the Indiana Audubon Society to improve nesting habitats for the endangered loggerhead shrikes in the society’s Shrubs for Shrikes program through its Adopt a Shrike program, says Gillet. Other conservation efforts include the Indiana Marsh Bird Survey program and the Indiana Birding Trail, a collaboration with Indiana Audubon Society and Audubon Great Lakes.

With grassland birds identified as one of the targeted groups in the Decline of the North American Avifauna survey, Indiana is doing its part to protect these birds by expanding their current Grasslands for Gamebirds and Songbirds program and designating an additional 19 counties to their current 21 focal regions. Thus far, it has been highly successful, says Gillet. “We have worked on 182 projects and affected over 2,500 acres of habitat.”

Now the habitats of wetland and grassland birds are threatened. More than half of Indiana’s 800,000 acres of wetlands are endangered due to the recent passage of Indiana Senate Bill 389, signed by Gov. Eric Holcomb in April. Though it is difficult at this point to identify the impact the bill will have on birds, says Jahn, the law is “worrisome because so many wetlands in Indiana have already been impacted.” Jahn, along with IU’s Ellen Ketterson and Matthew Houser, outlined their specific concerns in an op-ed published in the Indianapolis Star in March. “Many birds depend on wetlands,” says Jahn, “so further stripping protections to the habitat they need is not a step in the right direction for preserving biodiversity in Indiana.” Despite the requests of more than 100 groups to veto the bill, Holcomb enacted a law that many believe will fail to protect Indiana wetlands.

This peregrine falcon, Kinney, was a longtime participant in the Indiana Department of Natural Resources’ banding program. The DNR began reintroducing peregrines in Indiana in 1991. Kinney made his home in downtown Indianapolis, before dying in 2012 at 19 years old. He was believed to be the oldest and most productive peregrine in the Midwest, having fathered a combined 61 young with his mate of ten years, KathyQ, and a previous female. | Photo courtesy of Indiana Department of Natural Resources

With technology, ecologists, ornithologists, and other scientists are pushing the envelope, trying to understand before it’s too late why birds migrate. For many, the findings of the 3-billion-bird-loss study was shocking. For Scott Weidensaul, some of these advances feel like they are happening in just the nick of time. “Thank goodness that we have gotten to this point technologically,” says Weidensaul. “If we were still using the technology that we had twenty years ago, these questions would have been unknowable.”

Citizen science and eBird

In the birding world, technology is not the only king, nor are scientists alone in using technology to generate research data. Globally, millions of birders and citizen scientists — who not only participate in banding, annual counting programs like the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, and other conservation programs — share the information they have observed with others through the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird database. The scientists at the Cornell Lab are the real “kings of citizen science,” says Weidensaul. eBird is one of the more significant biodiversity citizen-science projects available today, with more than 100 million annual sightings globally, and those sightings grow almost 20 percent every year.

Here’s how it works. Birders can download the free mobile app to their smartphone or tablet. Once a bird is observed, the information can be entered into eBird. Users can also find birding hotspots, share their sightings with other birders, and use eBird to track their “life lists,” a cumulative personal record of bird observations. Researchers have access to these on-the-ground observations and couple this data with other tracking efforts from, say, Motus tracking information. An active submitter to eBird, David Rupp uploads his bird list after each tour that he gives. eBird is a premier citizen-science program, he says.

For a researcher like Alex Jahn, a lot of the research they do now via the study of gene expression in birds and GPS tracking data isn’t reliable without these on-the-ground observations. “With eBird data, we can use programs that allow us to compare GPS tracking data for a dozen American robins with the entire species on eBird,” says Jahn. “One method validates the other data.”

The science of tracking birds through migration is only just beginning to make headway, and scientists are just starting to understand why birds migrate when they do and how they do it. Technology has opened those doors wider and expanded our ability to encompass the whole of a bird’s lifespan. If birds are predictors of environmental change, or, as Jahn calls them, sentinels, they are critical for us as humans.

Unfortunately, as humans, says Weidensaul, we have stacked the deck against the birds. But he is hopeful: “The physical abilities that birds have — their navigation abilities, never mind the fact that there are 10,500 species in every environment on the planet except for the middle of the Arctic plateau — I would argue that they are among the most astonishing creatures on Earth.”