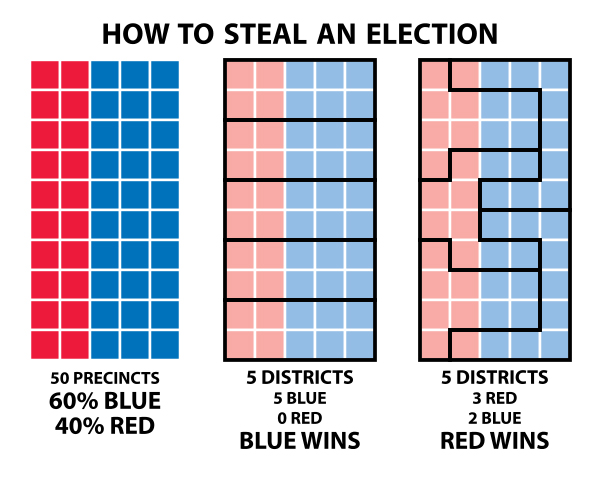

This illustration shows gerrymandering in its basic form. | Illustration by Steve Nass

If most Americans think climate change is real, perilous and remediable, why don’t they do something about it? If they want health care for all and stricter gun regulation, why does government policy fail to deliver? Why did this new century begin with two presidential candidates who lost the popular vote but won the White House? Why did government appoint to the Supreme Court of the United States a judge opposed by most Americans, including thousands of legal authorities?

The simple answer would be MONEY. We saw its raw power in 2008, when government bailed out the very Wall Street moguls who caused the financial crisis, did little to keep them from repeating their crimes, and put none in jail. Its power grew in 2010, when the Supreme Court decided 5-4 that money was so like speech that Congress could not regulate campaign spending without violating the free speech protections guaranteed by the Constitution (Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 2010). The subsequent flood of money into a market of elections for sale to the highest bidder did much to convert representative government into a dance-to-my-tune plutocracy. Not that simple? Maybe not, but it’s close.

Where do gerrymanders come from? Money certainly helps. Every ten years, following the national census, states draw up new district election maps to take account of population changes, with the intent of keeping districts more or less equal in size. Please note that the underlying principle here is representative government, wherein every Congressional district represents about the same number of people as every other district. With the advent of modern computer technology, it has become relatively easy not only to draw these new maps but also to jigger them for partisan advantage — in other words, to manufacture gerrymanders. And as we all know, to manufacture anything costs money and labor: in this case, money to buy or rent the necessary computers, software, and data and pay technical experts to do the necessary work. It’s not cheap, and it requires some deep-pocketed person(s) to get the job done. That’s where money comes in. What do the investors expect in return? Political influence. And why do we need public financing of elections? So the influence will serve the public instead of narrow private interests.

Former Bloomington Mayor Tomi Allison (far right) and Indiana University Professor Emeritus Jim Allison (second from right) say our democracy is in urgent need of reform to give voices back to the majority of Americans. At Inaugurate the Revolution last year, the Allisons discussed gerrymandering as one of the key reforms needed. | Limestone Post

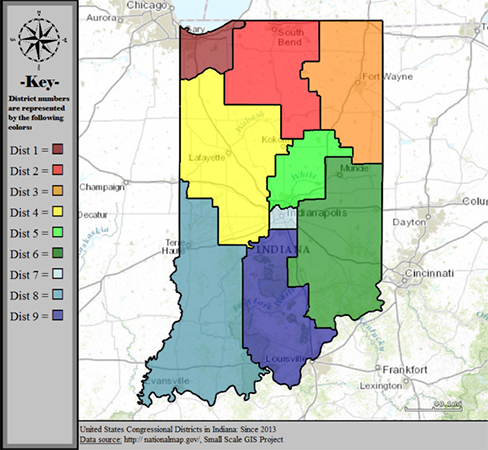

Take our Indiana gerrymander. Our legislature shows little interest in representative government, as evident from the gerrymander engineered in 2011. The tracks of that gerrymander are plain to anyone. In 2011, the Republican legislature devised and approved a redistricting plan that produced the following result in the 2014 election: With only 57 percent of the popular vote, Republican candidates won 70 percent of the House seats in the Indiana legislature. Similar results occurred in the federal races for Congress. In this year’s Indiana congressional elections, Republicans won about 62 percent of the popular vote and 78 percent, or seven out of nine, of Indiana’s seats in the U.S. House of Representatives; Democrats won about 38 percent of the popular vote but only 22 percent of the seats, or two out of nine. A typical result of Indiana’s gerrymander. But this is beginning to change in other states — Michigan voted for an initiative to adopt a nonpartisan redistricting commission independent of the legislature. The state voted 61 to 39 percent in favor of the proposal, despite well-funded disapproval by the DeVos family, the Koch brothers, ALEC, and the Michigan Chamber of Commerce.

Indiana’s congressional districts have looked like this since 2013. | Public Domain

Importuned by a citizen coalition led by Common Cause, the League of Women Voters, and other organizations, the Indiana legislature has essentially ignored public demand for a more representative redistricting system. Nothing radical, just a bipartisan redistricting commission independent of the legislature. Let the voters choose their legislators, not the other way around. How long can the legislature ignore with impunity this growing public demand?

Reverse Citizens United, with several co-sponsors, is convening a meeting of citizens and organizations on November 15 to examine why our government, supposedly a representative democracy, seems so out of sync with the majority of Americans. During this gathering, from 7 to 9 p.m. in the auditorium of the Monroe County Public Library, we hope to address many of these questions and explore how vote suppression, the gerrymander, and dark money have contributed to the subversion of representative government in America.

This November 15 event will feature a call to action on November 20, Organization Day for the 2019 General Assembly. On that day, The Indiana Coalition for Redistricting Reform (All IN for Democracy) will host a rally at the Statehouse to show legislators and Governor Eric Holcomb that we want redistricting reform in Indiana.