[UPDATE: On September 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an agency order, which says, “a landlord, owner of a residential property, or other person with a legal right to pursue eviction or possessory action, shall not evict any covered person from any residential property in any jurisdiction to which this Order applies during the effective period of the Order.” The effective period is from September 4 through December 31, 2020.

Tenants, lessees, or residents of residential properties must provide an executed copy of a Declaration form to their landlord, owner of the the residential property where they live, or other person who has a right to have them evicted or removed from where they live. “Each adult listed on the lease, rental agreement, or housing contract should likewise complete and provide a declaration. … These persons are still required to pay rent and follow all the other terms of their lease and rules of the place where they live. These persons may also still be evicted for reasons other than not paying rent or making a housing payment.”

Many of the issues explained in the following article could become concerns again by the end of this year when the national evictions moratorium ends.]

[PUBLISHER’S NOTE: In collaboration with WFHB Local News, LP contributor Diane Walker has produced an ongoing series, titled “Eviction Crisis in Indiana,” in which she interviews many of the people in this article, including Deborah Myerson of South Central Indiana Housing Opportunities, Forrest Gilmore of Shalom Community Center, Jacob Sipe of Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority, and Jamie Sutton of Justice Unlocked. Visit WFHB Local News to hear all episodes.]

My neighbor Marissa and her son, Caden, are walking through my neighborhood and stop to admire my cats, who are outside with me as I’m sitting on my stoop. “He likes to tell stories,” she tells me, laughing as Caden, a boy with killer eyelashes, tells me excitedly that he has both a Spiderman and an Avengers face mask. “Cats like Avengers,” he tells me with the assurance only a four-year-old can muster. “Who doesn’t?” I respond, as my cat rubs up against his legs and sticks an inquiring nose into Caden’s juice cup. (Names have been changed for reasons of privacy.)

“The last time I talked to you, I had just found out I was pregnant,” Marissa tells me. “Well, I just found out I’m pregnant again.” She rolls her eyes, and laughs again. She tells me that her employer, a local restaurant, had laid her off for two months, but she started working again at the end of May. Marissa’s husband, Bob, was able to keep his job as a delivery driver for the same restaurant, but her unemployment claim was denied, so she had no income for about two months. I know my landlord is good at working with tenants about rent — they’ve worked with me before — but I ask her hesitantly, fearful of prying, if she needs help with rent since I know restaurant work doesn’t pay much.

Many families have been able to stay in their homes due to a moratorium on evictions issued by Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb. Various forms of rental assistance is available. | Limestone Post

I’m the managing attorney of a local legal aid, District 10 Pro Bono Project, and my organization cosponsors a project at the Monroe Courts called Housing and Eviction Prevention Program (HEPP), a project designed to prevent evictions. Despite the legal aid, mediation, and the housing navigation this project offers, being able to pay rent will greatly help a tenant’s chances of staying.

Marissa confirms that she and Bob are behind in their rent. The state of Indiana has money to help people pay rent, I tell her, based on income and people’s housing situation. “Oh, I’m definitely interested,” she says, as she takes the website info I offer. It’s the first she’s heard of it. “I’m going to apply right away,” she says. She thanks me for both the cat petting and the information as she leads Caden back across the parking lot to their apartment for more orange juice.

Marissa and her family have been able to stay in their home due to executive orders by Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb. Holcomb first ordered a moratorium against residential evictions on March 19 as part of early pandemic orders “to avoid the serious health, welfare, and safety consequences that may result if Hoosiers are evicted or removed from their homes during this emergency.”

Since that time, landlords, tenants, courts, and housing advocates have held their breath at the end of every month, wondering if the coming month is when the eviction hammer might drop — and it hasn’t, because the order has been renewed four times for thirty days at a time. But the fifth and latest extension order, from July 30, extends the moratorium on evictions for only two weeks, a sign that no more extensions may be coming. Evictions may begin for a large portion of Indiana on August 15.

A vast problem

The end of the moratorium comes at a time of unprecedented economic distress in the United States, with the economy contracting at a rate of 8.2 percent from April through June, for an annual rate of 32.9 percent, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Thirty-five percent of Hoosier households who rent their homes, or 18 percent of all Hoosier households, say they have “no confidence” or “slight confidence” that they can pay next month’s rent, according to a Household Pulse Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, for the week of July 16-21. The survey indicated 22 percent of Hoosiers didn’t pay their July rent.

More than half of those households, like Marissa and Bob’s family, include children under the age of 18. Seventy percent of the renters who did not pay July’s rent had children; 55 percent of renters who doubt they’ll be able to pay August rent have children.

Stout Risius Ross, a bank and global advisory firm, has used the Household Pulse surveys to predict that there will be 211,000 evictions in Indiana over the next four months. By way of comparison, according to the Princeton Eviction Lab, there were 31,767 evictions in Indiana in all of 2016, the latest year statistics are available.

Deborah Myerson, executive director of South Central Indiana Housing Opportunities. | Courtesy photo

“The cascade of impact is going to be so big that it’s not just going to be blown off as ‘those people’ who are lazy and can’t take care of themselves,” says Deborah Myerson, head of the local nonprofit South Central Indiana Housing Opportunities (SCIHO). “It’s everybody. You’ve got at least 200,000 people who are going to be getting evicted.”

There is some help, as I told Marissa. Indiana originally set aside $25 million from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, and on August 5, added another $15 million in CARES funds for a total of $40 million. There is also a total of $31.5 million for people who are experiencing homelessness or are at risk of becoming homeless, according to Jacob Sipe, the executive director of the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority (IHCDA). IHCDA oversees the rental assistance portal through which Hoosiers in 91 counties (Marion County has a separate pot of money) can apply for rental assistance.

How rental assistance works

Sipe says there are two kinds of assistance for people who have experienced a loss of income through layoffs or reduction in hours or the loss of a job due to COVID-19. One is through the CARES Act, which is $500 a month for four months, or $2,000 total. This assistance supplements rental payments, and can be used for current or back rent, but does not pay total rent. The other assistance comes through federal Emergency Solutions Grants, or ESG, designed to pay up to six months of a household’s entire rent for families or renters whose income is 50 percent of average median income in Indiana, or $27,163 for an individual. IHCDA presently has $13.5 million in ESG money, which was intended to pay six months of rent for about 1,500 households, since some of the ESG money must be used for outreach, publicity, and administrative costs. Sipe is expecting an additional $18 million in these funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Renters can apply at indianahousingnow.org.

Jacob Sipe, executive director of the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority (IHCDA). | Courtesy photo

“One of the things that we’ve tried to eliminate for folks that were experiencing this trauma was to say that there’s one way to apply,” Sipe says. “We’ll identify the right program that will provide the best benefit for you, and that’s how we came up with the rental assistance portal.” IHCDA, which is assisted by 63 local agencies throughout the state — including nonprofits (such as Shalom Community Center in Bloomington), housing authorities, and local trustees — is determining who is eligible for which assistance.

The landlord is notified by email when a renter applies through the portal, according to Sipe, and if the landlord agrees to accept the possible rental assistance as payment, the landlord and tenant sign an addendum to their lease, which allows for the payment assistance to go directly to the landlord.

There are problems with this system, according to both Sipe and Jamie Sutton, an attorney and executive director at Justice Unlocked, a nonprofit in Monroe County that offers legal services on a sliding scale based on income. “The trouble is that there’s no right to cure [past-due rent] under Indiana law once an eviction is filed,” says Sutton. This means the landlord could refuse to accept the tenant’s offer of payment through IHCDA, and still evict. Nonpayment of rent is an absolute reason to evict under Indiana law, Sutton says, which is part of the reason for the eviction moratorium.

While Sutton and Sipe note that most landlords have a strong financial incentive to take the offered rental assistance, both also point out that landlords who want to evict a nonpaying tenant for other reasons — anything from a valid breach of lease to dislike of a tenant — are free to refuse the assistance and turn the tenant out after a legal eviction is filed.

But the larger problem is that there just isn’t enough money for the people who need it. Sipe says that as of August 5, IHCDA had received 25,000 applications for assistance, but they were initially expecting to help only 10,000 to 12,500 applicants with about $2,000 apiece. Most people are requesting the maximum of $2,000, Sipe says, so, with the additional $15 million, another 7,500 applicants can be helped.

Some of those applications will be funded by ESG money, since there will undoubtedly be applicants in that group with less than 50 percent of average media income, who are eligible for six months of payments of the total amount of their rent. Sipe says that IHCDA was planning to help 1,200 to 1,500 households with the $13.5 million of ESG money. With the additional $18 million of ESG coming in from HUD, IHCDA will be able to help more households with the second installment of ESG. But while the IHCDA, with a total of $71.5 million in rental assistance, can serve the current number of applications, many more may be coming in as the end of the moratorium approaches.

Stout, Risius and Ross, the same consulting firm which predicts 211,000 evictions in Indiana, predicts that 313,000 households are at risk of eviction. “At risk of eviction” means that there is a problem with paying full rent, but the fact that “only” 211,000 of those renters are evicted means that the households who avoid eviction get assistance, successfully negotiate with their landlord to stay, or borrow or otherwise obtain the rent money owed. It may mean that some at-risk renters leave their current homes to move in with friends or family, or try to find less expensive housing, thus leaving so that there is no judgment of eviction.

Stout also predicts a $284 million shortfall in rent paid to landlords throughout Indiana.

Sipe is not going down without a fight, and he says there are no plans to close the rental assistance portal, although keeping it open might depend upon how quickly HUD gets the final ESG installment of $18 million to IHCDA. As of July 29, he didn’t know when HUD would send the money. It is also promising that Indiana allocated an additional $15 million in CARES funds to IHCDA for rental assistance.

“We’re working to continue to identify money to try to help as many people as we can,” Sipe says. He admits it keeps him up at night. “There’s the additional ESG money that we are expecting to get. There could be a potential of some philanthropic money that could come through. We’re looking for everything.”

It’s not surprising that there has not been enough money allocated. The CARES Act, which provided federal dollars for all the rental assistance available through IHCDA, was signed into law on March 20. Four months ago, no one could predict where we are now, with the pandemic still raging and economic indicators worse than they were even during the Great Depression.

How will evictions affect our neighborhoods?

If it turns out true that 35 percent of Hoosiers can’t pay their August rent, for those of us who live in neighborhoods where most people rent their homes, we might expect one out of three of our neighbors gone by fall, casualties of eviction. It could be worse in Bloomington, where the $893 median rent is higher than the state average, and 21 percent of Monroe County residents live in poverty.

The City of Bloomington Housing Study, published July 13, 2020, says that 60 percent of Bloomington’s renter households are “cost burdened” by rent, with people in “many neighborhoods” paying more than 30 percent of their income in rent. The survey also says the greatest shortage of housing is for renters with less than $25,000 in annual income. All of these measures suggest that if renters, particularly those making less than $25,000 a year, lose their current housing due to eviction or moving voluntarily, they will have significant trouble finding new housing in Bloomington.

The Bloomington Housing Study was published in July 2020 by the City of Bloomington. | Image by Limestone Post

Even if the housing market, always tough for tenants in Bloomington, softens so that landlords accept lower rent payments, there are hard times ahead.

“People have lower incomes. They may be working reduced hours, they may have lost a job, their unemployment is spent down,” says SCIHO’s Deborah Myerson. “Who knows what’s going to happen? It’s just a big, giant disaster.”

What does losing housing mean for a family like Marissa’s? The best scenario is that they leave their current apartment, still owing rent, but are able to find a new, more affordable place.

Being forced to move for financial reasons, even if a family can land housing somewhere cheaper, still creates stressors, according to Myerson. Housing is the first and foremost need that people have, because it’s the root and stability for so many other needs. For example, for working people, a move may make a job commute harder. A job may no longer be within walking distance or on a bus route, or could require a longer drive, eating up more time and money.

Although Bob needs a car to do delivery for the restaurant where they both work, Marissa can walk to work from where they live. Their employer allows them a schedule that lets her take care of the children while he works, and vice versa. If they move, can they keep that situation? Myerson gives another downside to having to move: There may not be the same choices at other living spaces. Where we live now is close to several grocery stores and shops, and there is a city park behind our complex.

A place where people live is more than just “bricks and sticks,” says Myerson. It’s a community. “Maybe there are neighbors you are really tight with, and you did stuff for each other, and if you move, you don’t have that anymore.” People you can rely upon are resources, “social capital,” in Myerson’s phrase, especially for lower income people, so that leaving that community can leave a family with less than they had before.

Some Hoosiers may leave their homes to move in with family, which has its own set of challenges. “If you are doubling up, are there tensions in the household?” asks Myerson rhetorically, because in that situation, there are bound to be tensions. All of this is particularly hard on children, she notes, “because they’re trying to set up important relationships outside of their family. And especially if their family is experiencing housing instability, there may be a lot of stresses within the household, so those outside relationships are really important [for children].”

Eviction is considered an Adverse Childhood Experience, or ACE, a term coined by a 1997 joint study between the Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente, according to the CDC’s website. The study, which still follows its initial participants, found that ACEs created lifelong challenges in the physical and mental health of children. “Evictions are destabilizing events that increase families’ financial stress and strip away the psychological and physical security of having a home. These effects are particularly traumatizing for children, who often suffer emotionally and academically,” according to ACEs Connection.

All of this instability is magnified by the pandemic, says Myerson, where children may or may not be able to be in school. She points out that schools provide not only education but also food for children, access to technology and social workers, and protections from the stresses from home. If schools are forced to close because of the pandemic, there is even less stability for children whose family’s housing is uncertain.

The worst case scenario for a family like Marissa’s is homelessness, couch surfing, living on the streets, in cars, or, after all other resources are gone, in shelters. “Homelessness beats people down, it doesn’t lift people up,” says Forrest Gilmore, executive director of Shalom Community Center, which provides services for people experiencing hunger and homelessness. “Once you’re in homelessness, it’s much harder to get back out of it. So it’s much easier to move into a new place, as opposed to going into homelessness, and then go back, moving into a new place after.”

Shalom is one of the places administering the ESG money mentioned above. Beginning the week of August 3, says Gilmore, Shalom will have a staff member in place who, among other duties, contacts landlords to see if they will accept the ESG money that rental assistance applicants may receive to keep their housing.

Shalom Community Center, on South Walnut in Bloomington, is helping to administer federal Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG) for renters. | Limestone Post

Shalom is committed to keeping families and people from losing housing altogether, because not having a home takes so much away from people. “There’s the trauma, the fear, the terror of not knowing what to do,” Gilmore says. “There’s losing precious heirlooms. If you have pets, sometimes it’s giving up pets, you lose your ability to clean yourself easily, your ability to stay warm, your ability to stay cool, so that affects hygiene, so that affects your ability to be employed. There’s transportation issues, and it just goes on and on and on.”

Indiana courts’ response to the problem

If a family can’t get money for their rent, then leaving their current home might be inevitable. But even then, the more time they have to leave, the better, says Gilmore. This is part of the reason why Indiana courts have put together a Landlord/Tenant Task Force to give recommendations to all state eviction courts in handling the deluge of evictions that are expected to happen.

Among the recommendations of the Landlord/Tenant Task Force is to set new evictions — those filed after the state eviction moratorium ends on August 14 — to thirty days from the day the landlord first files for the eviction. The pre-pandemic scheduling for eviction hearings was much shorter, often two weeks or less.

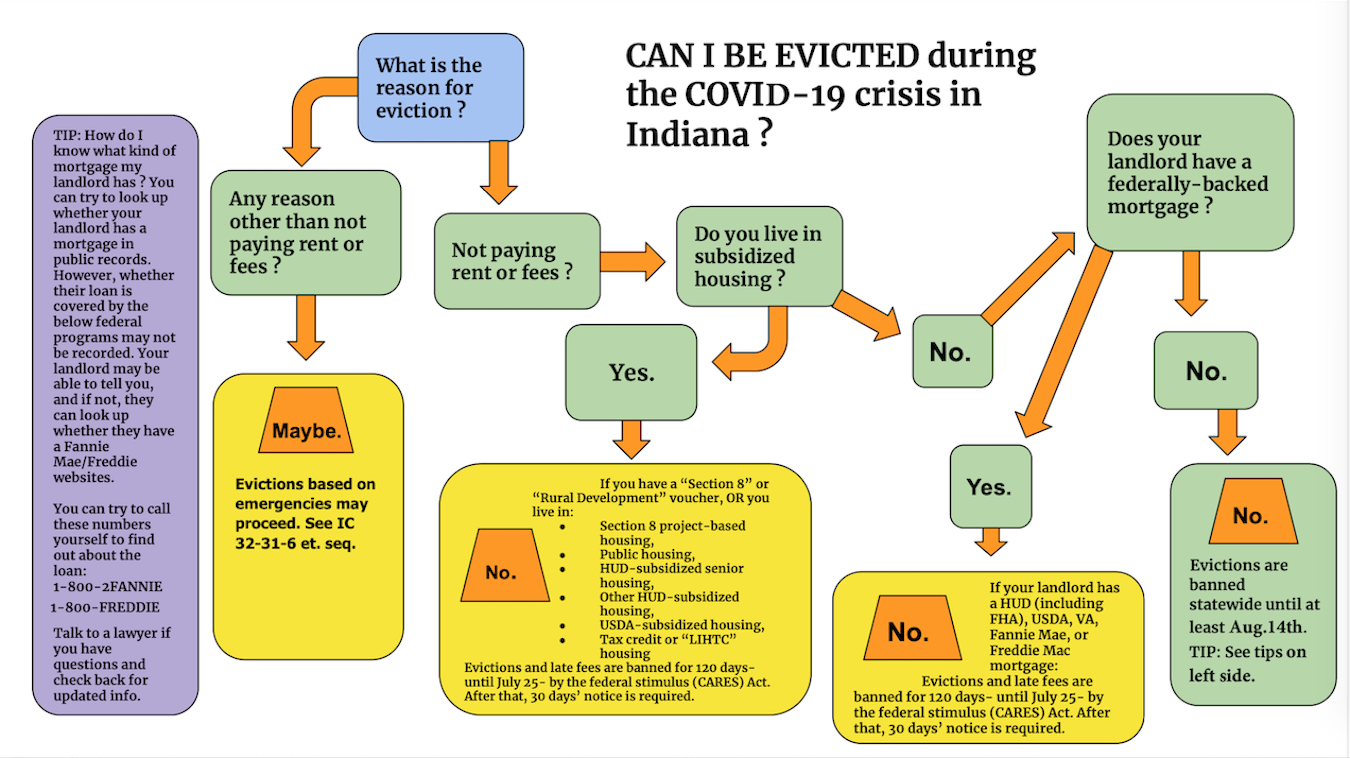

The Task Force is careful to say that the recommendations are “presented mindful that every court is different and there is not one right way to handle the eviction process once the moratoria are lifted.” Thus not every court might follow the guidelines, because they are not mandatory. Courts do have to preserve the rights of tenants who live in federally backed housing and have additional protection from eviction by the CARES Act. The eviction moratorium for federal housing doesn’t end until August 31, and unlike private landlords, landlords for federally backed housing must also give their tenants thirty days’ notice of the eviction. Federal tenants may also qualify for lower rents if they’ve lost income due to the pandemic.

Federally backed housing includes Section 8, income-based housing, HUD housing, and housing for the disabled and elderly. A complete list of tenants protected by the CARES Act can be found here.

This chart is from the Landlord/Tenant Task Force report, created by Indiana courts to give recommendations to all state eviction courts in handling evictions that are expected to happen when Indiana’s evictions moratorium expires. The Landlord/Tenant Task Force report, including this graph (Appendix B) can be found here.

Monroe County evictions courts will follow the Task Force guidelines of setting new evictions thirty days after the initial date of filing, according to an email sent to local attorneys by Monroe County judges Catherine Stafford and Judith Benckart. Stafford and Benckart have also sought input from landlords and their attorneys about handling the evictions, and they say the judges will refer both the tenants and landlords who are unrepresented by attorneys to help from the local Housing and Eviction Prevention Program (HEPP) project, which is in the Charlotte Zietlow Justice Building, where evictions occur. HEPP helps both landlords and tenants with legal advice, mediation assistance, and housing navigation, should tenants need to find new housing.

Stafford and Benckart also encourage landlords to accept “agreed judgments” instead of an eviction. An agreed judgment is a court order reflecting an agreement between the landlord and tenant to allow the tenant to leave without an eviction, and allow the tenants to pay amounts owed in installments. “Evictions are a pretty serious mark against your record,” says Gilmore. “And it makes it incredibly difficult [to find new housing]. One eviction makes it hard. Two evictions make it almost impossible for you to find a home because landlords just won’t take a chance on you.”

The Charlotte Zietlow Justice Building on North College is where evictions will resume when the evictions moratorium ends. It also houses the Housing and Eviction Prevention Program (HEPP), which offers legal aid, mediation, and housing navigation services for renters. | Photo by Paige Strobel

The Task Force guidelines, which suggest scheduling eviction hearings thirty days from the date of filing the eviction, is useful to tenants in trouble, notes Gilmore. “Any time anyone has more time to seek out and search for a new place, that’s to their betterment.”

Delays may put extra pressure on landlords though, some of whom are mom-and-pop businesses who have little insulation from loss of income themselves. “I’m getting inquiries from landlords who say, ‘My tenant hasn’t paid rent in the last four months, and I need to pay property taxes, I need to pay for maintenance on the building, I have no way of doing that,’” says Myerson. Landlords may be able to postpone mortgage payments themselves pursuant to other provisions of the CARES Act.

But the larger solution, says Myerson, is that people need money for their rent. “That money needs to be out in the economy.”

Is more money coming for rental assistance?

U.S. Senate Republicans introduced the Health Economic Assistance, Liability Protection and Schools (HEALS) Act on July 27. A review of the bill shows that it provides funding for low-income federal housing but none for other rental assistance. U.S. House Bill H.R. 6800, introduced by House Democrats on May 12, allocates $100 billion in further ESG money for rent at or below 80 percent of the average median income for their area. ESG money is the source of 44 percent of the funding IHCDA currently has for rental assistance.

(A congressional summary and full text can be found for the Senate bill and for the House bill on Congress.gov.)

The Senate and House of Representatives are still debating what additional coronavirus relief there will be, but both sides hope to have a deal soon. The legislation will include a second stimulus check of $1,200 per person, predicts Associate Professor Brad Fulton of the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University. Only minor differences exist between the Senate Republicans’ proposal and that of the House Democrats regarding a second stimulus payment.

But there are two main sticking points, insofar as working people who rent are concerned, which could delay agreement, Fulton says. The first is whether there will be $200 in federal supplements to state unemployment, as Senate Republicans propose, or $600 as proposed by House Democrats. Fulton says he believes that Democrats and Republicans have each signaled they’re willing to compromise, and may reach $400 as a supplement.

Deborah Myerson of SCIHO says that where people live is more than just “bricks and sticks.” It’s a community. “Maybe there are neighbors you are really tight with, and you did stuff for each other, and if you move, you don’t have that anymore,” she says. Pictured is B-Line Heights, an affordable housing project on North Rogers Street. | Limestone Post

The second problem is whether there will be any financial assistance to state and local governments, including rental assistance provided by the CARES Act. Fulton believes not, because the Senate has not put anything on the table to move on, although the House has done so. “This isn’t getting as much press because it’s more abstract, it’s less quantifiable, but it has a huge impact,” says Fulton. “Every state and local government is being hit with a reduced tax base.” Without an agreement from the Senate that money should be appropriated to state governments, there is no rental assistance for landlords and renters hit by the pandemic’s economic consequences.

Unemployment and stimulus payments could assist with payments for rent. And, especially if Indiana is stopping its moratorium against residential evictions with private landlords, renters may be motivated to use that federal stimulus payment for rent.

If there is no federal money for rental assistance, could there be money from the state of Indiana? According to Holcomb’s 2020 State of the State address, “We set aside $2.3 billion in our state’s savings account, which is in stark contrast to some of our neighbors.” Fulton acknowledges that he does not follow state legislation as closely as he does national legislation, but he says he presumed the state set that money aside as emergency “rainy day” funds.

“And it’s a rainy day,” Fulton adds.

Indiana State Senator Mark Stoops (D–District 40) agrees. “Indiana has a surplus, and if we broke into that surplus we could definitely make it easier and we could help solve a huge problem.” He says that even the surplus of $2 billion could “go down the tubes pretty fast” during this crisis, and that “Indiana’s priority should be making sure you don’t have this huge percentage of the population that’s suddenly on the brink.”

Stoops says he and other legislative Democrats have been requesting a special legislative session in August or early September, but that it is more likely that Governor Holcomb may make unilateral decisions about any funding. Holcomb’s deciding to make spending decisions without the legislature’s input is not technically legal, Stoops says, but there is precedent for it.

Legislators can be pressured to pressure the governor, who should also be contacted, Stoops says. “Every elected official should hear about [the eviction crisis]. Anytime you talk to any elected official, or even the governor, let them know what your story is.”

“It’s not just, ‘I want this to happen.’ Say why it’s important to you, the situation you’re in, how you can describe it,” says Stoops. “Say, ‘This is my story,’ where they can understand how this is unfair or some little bit more here or there would change the situation.” An appeal to the emotions and an example is the best way to effect change from an elected official, he says.

A time of uncertainty

No one knows for certain what will happen, of course. Landlords and tenants might be able to negotiate payments for less than the lease allows. There may be more rental assistance coming to help both renters and landlords. Court action might be able to keep renters in their homes long enough for them to land somewhere promising while not putting the brunt of the catastrophe on landlords. Renters might be able to stave off upcoming rental payments with unemployment benefits or stimulus checks. The state of Indiana could rescue its citizens, and its economy, with both rental and mortgage payment assistance. (Mortgages are also facing crises points — but that’s another story.)

For Marissa and Bob, I hope my landlord works with them. I hope Caden gets to come by and pet my cats as often as he wants, and tell me stories about The Avengers. If that can’t happen, I hope Marissa and Bob can deliver their new baby in a place they can call home for a while. I hope that they, and all of our neighbors, can stay safe and stable as possible, considering the storm that’s coming.

[UPDATE: On August 26, the Rental Assistance Portal at www.indianahousingnow.org stopped accepting applications, and the state has no plans to reopen it or fund more rental assistance. On the same day, Indiana Supreme Court Chief Justice Loretta Rush announced the launch of the Landlord and Tenant Settlement Conference Program. The website states, “The Landlord and Tenant Settlement Conference Program is a way to help residential landlords and tenants talk about their situation with the help of a ‘facilitator,’ a neutral helper, to see if a settlement can be reached before an eviction case is filed or, if an eviction case has already been filed, to see if an agreement can be reached between the parties before the court makes a decision in the eviction case. There is no cost to participants for participating in this program.”]

>

Help List for Renters

— Apply for help with rent payments at IHCDA’s Rental Assistance Portal

— Talk to your landlord; explain you’ve applied for money to pay the rent owed. Let them know it takes about two weeks to get a response as to whether you’ve been accepted.

— Talk to your landlord; explain you’ve applied for money to pay the rent owed. Let them know it takes about two weeks to get a response as to whether you’ve been accepted.

— Check the news on August 12 or after to see if the moratorium has been extended beyond August 14.

— If your landlord has tried to evict you, or has taken measures to force you out — such as disconnecting utilities or removing appliances — during the eviction moratorium, file a complaint against your landlord with Indiana’s Attorney General, here.

— If you have been discriminated against, file a complaint with the Indiana Civil Rights Commission here.

— If there has been an issue with the tenancy on the landlord’s end, seek legal help from one of the agencies below.

— Tell your story to an elected official, such as a state or federal congressperson or senator, the governor, city or county authorities.

—Diane Walker

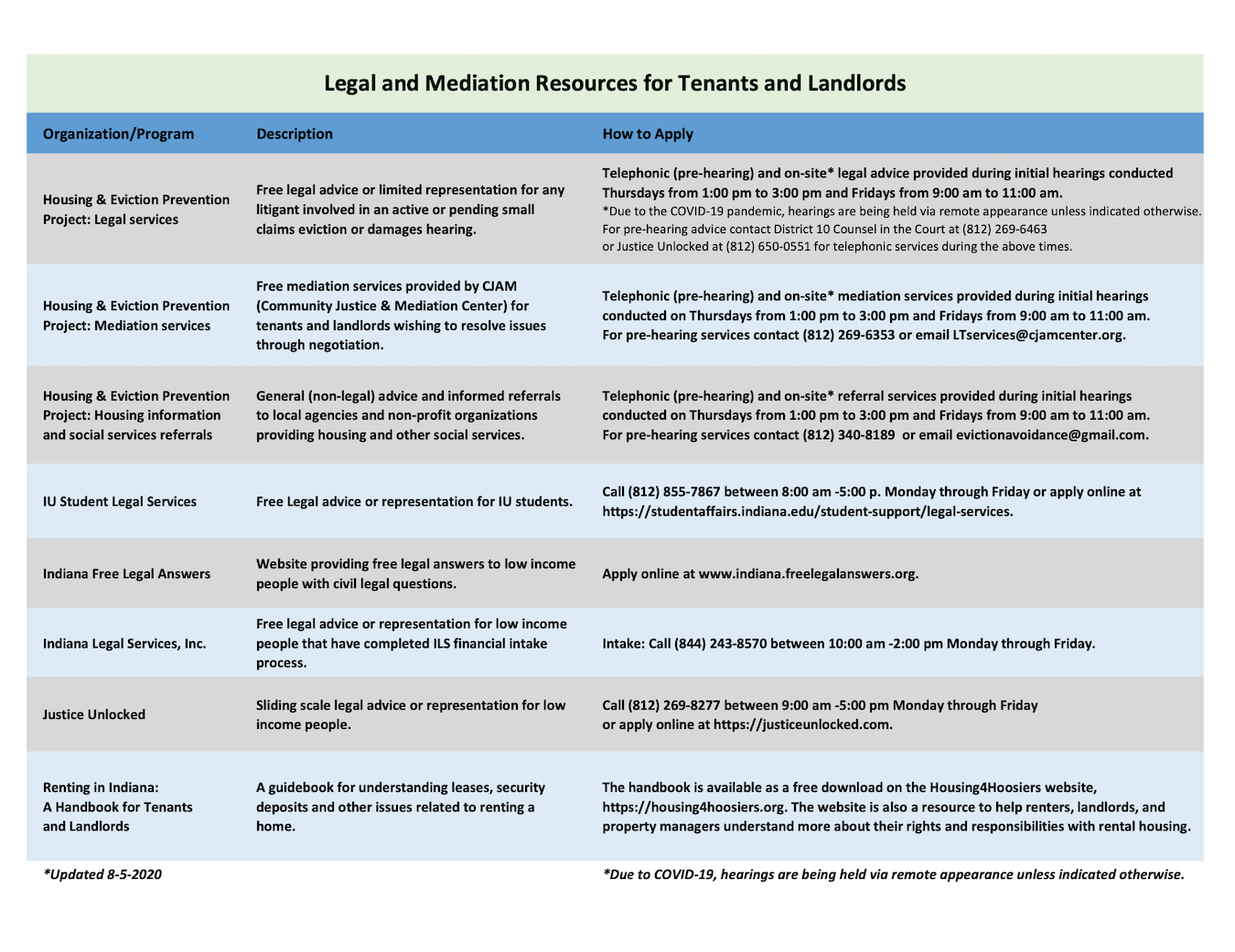

The first four resources listed above for tenants and landlords are only in Monroe County. More legal help can be found here. | Image courtesy of the Housing and Eviction Prevention Program (HEPP)