[Editor’s note: This story was originally published by Limestone Post on October 17, 2017. Recent news shows the prime issue this story addresses is still a problem. An online company announced it was no longer offering sexy Handmaid’s Tale costumes due to complaints that the costumes were offensive. And yet the company still offers a complete department of “Indian” costumes, such as the “Sexy Pocahontas.”]

Writer Laura Martinez, wearing traditional Apache dress, speaks to a group of people at Sample Gates. As Halloween approaches, consider if your costume appropriates another’s culture. | Courtesy photo

Every fall, people gear up for Halloween — some go for scary costumes, some cute, some sexy. And every year, one can enter just about any costume shop in the U.S. and find costumes that appropriate marginalized cultures by promoting stereotypes and mocking a variety of communities.

Costumes such as “Indian Princess,” “Pocahottie,” and “Indian Chief” are offensive to indigenous cultures. Other offensive and inappropriate options include “Mexican” costumes featuring an oversized mustache, sombrero, and poncho; “Geisha” costumes with a stereotypical and cheaply made Japanese kimono, wig, and often a face-paint kit; “Arab” costumes often containing a fake bomb strapped to the chest of a stereotypical costume. And there are more. As a Native American person, I cannot speak with any authority on the offensiveness of the other costumes, so I will focus on the “Indian” costumes that litter the walls of nearly every costume shop and show up at many Halloween parties.

I, personally, find “Indian princess” costumes to be the most problematic out of the various costumes that people purchase every year. Today in North America, Native American women are two-and-a-half times more likely to be sexually assaulted than their non-Native peers. Eighty-six percent of the assaulters of Native women are non-Native. These “sexy” costumes perpetuate the stereotype that Native American women are more sexually available than their non-Native peers.

And out of those “Indian princess” costumes, I find the “Pocahottie” and “Sexy Pocahontas” costumes to be the most disrespectful, considering the real Pocahontas was a 10- to 12-year-old girl who was kidnapped and raped, and then taken to England, forced to marry a man named John Rolfe, and paraded around as the “civilized savage,” before dying in her early 20s. She is a tragic figure in Native history, not Disney’s buxom woman who saved John Smith’s life. (This portion of the Pocahontas story is debated by historians as to whether or not it is factual, but if it is, she was about the age of 10 when she was first kidnapped.)

Historically, European colonists used sexual assault as a tool of colonization, meaning they sexually assaulted women as a means of control. For example, Spanish colonists often would imprison Native men and women inside missions, where the women were repeatedly victims of sexual assault. Today, it is known that victims of sexual assault often experience higher rates of depression and post traumatic stress disorder. Furthermore, repeated sexual assault can lower immune systems, leaving women more susceptible to crowd diseases (such as smallpox and influenza) and sexually transmitted diseases. According to Amnesty International, “Sexual violence against Indigenous women is the result of a number of factors and continues a history of widespread human rights abuses against Indigenous peoples in the USA. Historically, Indigenous women were raped by settlers and soldiers, including during the Trail of Tears and the Long Walk. Such attacks were not random or individual; they were tools of conquest and colonization.”

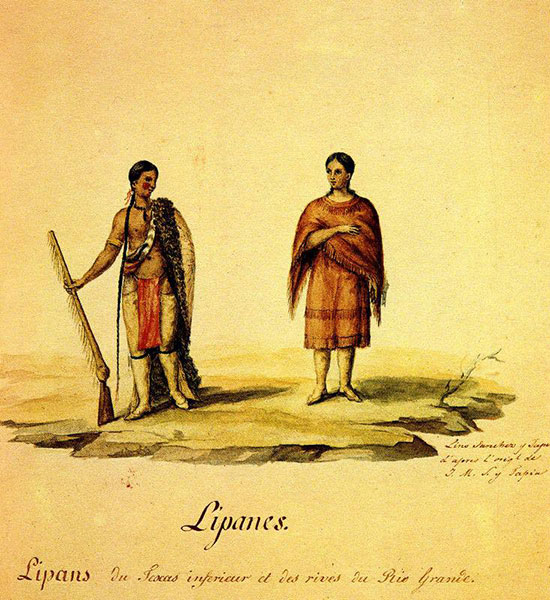

Martinez says, “All Native costumes portray stereotypical and incorrect versions of historic Native dress.” | Painting by Lino Sanchez y Tapia, circa 1828

The women who wear these “sexy Pocahontas” costumes are often unaware of the violent history of sexual assault on Native American women, but their decision to wear these costumes — regardless of their awareness of this history — still perpetuates the stereotype of Native women as being more sexually available than non-Native women. One common argument is that costume shops also sell “sexy cop” or “sexy firefighter” costumes and that the sexy Native costumes aren’t any different. However, people choose to become a police officer or firefighter whereas people do not have a choice in their race or cultural identity. Professions are not equivalent to race.

While costumes for men and children do not contribute to the hypersexualization of Native women, they are still problematic. All Native costumes portray stereotypical and incorrect versions of historic Native dress. They often feature fake buckskin outfits with fringe and fake headdresses or feathers. In Native American cultures, feathers are important and sacred, and in many nations, every feather a person wears is earned.

Feathers are not just random adornments. They have deep spiritual and cultural significance. Fake headdresses, for example, mock and belittle the cultural significance of feathers and headdresses. The stereotypical headdress that is most often seen in costumes is modeled after the northern Plains-style headdress because that is what is most commonly seen in film. Hollywood and advertisements throughout the last two centuries have contributed to the stereotype of Native cultures being one singular culture, and these costumes play into that myth. There are more than 500 different Native American nations in the United States alone, and we are not a homogenous population, meaning each nation has its own distinct culture, religion, and language. These costumes, which can often be seen hanging on a rack next to monsters and medieval knights, also promote the myth that Native people are not “real” people, just like a monster, or the myth that Native people are a people who no longer exist, like a knight. Furthermore, it reinforces the stereotype that Native American people are “stuck in the past” or not a modern people, when most of us today live in modern homes or apartments and wear western clothes.

If people from a specific race or culture say that a costume, mascot, or portrayal is racist, people who are not from that group do not get to say whether or not that group should find it racist. Recently, I had an interaction on social media with the owner of a costume shop after I asked if they were selling racist Halloween costumes again this year. I found the exchange, which the shop has now deleted, to be incredibly tone deaf and dismissive. And even after I posted screenshots of the conversation on my personal social media page, I had people on my friends list argue with me, claiming that they also did not believe that these costumes are racist. This is not a subjective opinion and it’s not something that one can agree to disagree on. If Native American people find these costumes to be racist, they are racist. To us, dressing up in red face and playing Indian is no different from someone wearing blackface, the historical tradition of white people painting their faces with black makeup or shoe polish and performing stereotypical and racist portrayals of African American people.

Halloween costumes perpetuate the mistaken idea that Native Americans are one homogenous culture and that they are stuck in the past. In this photo, Martinez, left, who is wearing a T-shirt with a traditional Apache skirt, sits with friend Margie King, a citizen of the Anishinaabe tribe. | Courtesy photo

As with almost any issue, individual opinions differ, however most Native American people do find these costumes offensive. While the practice of dressing up and “playing Indian” is not unique to the United States, according to writer Philip Deloria, it began as an American phenomenon in order for Americans to individualize themselves from Europeans. “There is this simultaneous embracing of Indians, which allows Americans to make claims of American identity,” he says. “But at the same time, in order to make a real physical nation, they have to dispossess those Indians.”

His book, called Playing Indian, explains the long history of people using Native stereotypes as a costume, dating back to the Boston Tea Party. It also does a good job at explaining why this is offensive to Native people, despite the fact that dressing up to portray a stereotypical version of another race or culture has become normalized in popular American culture.

We all need to bring awareness and thoughtfulness to our choices, particularly when this comes to marginalized races and cultural identity. We live in tumultuous times where white supremacy seems to be on the rise. While many people of color would argue that these white supremacists have always been there, as president, Donald Trump has made it more acceptable for them to come out of their racist closets and onto the public stage. For those of us who find this horrifying, remember to be more aware and more conscious of how your choices affect others and people of other races.