Good things are always happening in our public schools. It’s hard to see that if you read the news these days. There are all-consuming culture wars being manufactured by individuals far away. These outrageous, non-local stories are then pushed around talk radio and social media via algorithms creating nothing but trouble.

“Does my local high school have kitty litter boxes in their bathrooms?”

A good way to bust through the madness? Like and follow your local schools and school districts on social media — Facebook or Instagram — to get a glimpse into the schools. See the traditions, milestones, sports, and fundraisers. In a state where legislators fund students, not schools, a school’s social media efforts are strong, as it’s an affordable way to advertise. And public schools often welcome community members to volunteer a helping hand.

There are about 290 traditional public school districts across 92 counties in Indiana, educating about one million students, in which good things are happening. The majority of the counties in Indiana are rural. One such place is Orange County. Orange County is home to the West Baden Springs Hotel and its famous dome, commonly referred to as the “8th Wonder of the World,” as well as other notable sites such as Paoli Peaks and Patoka Lake. As such, Orange County generates a good deal of income from its tourism, casino, and recreation markets. It’s also where basketball legend Larry Bird, the “Hick from French Lick,” attended school. Although it attracts many visitors, the population of Orange County is quite small — just under 20,000 residents — as is typical of many rural areas in Indiana.

Orange County school districts

Orange County is also home to three tight-knit public school districts in which good things are happening to help create better, stronger communities. These public schools are working to overcome the challenges the children in their community face, via unique initiatives and innovative health-care partnerships. And yet, public schools in Indiana, including the Orange County districts, are facing key policy and budgetary challenges.

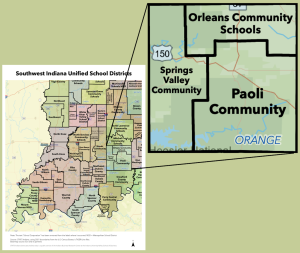

Orleans, Paoli, and Springs Valley community school districts in Orange County are part of the 290 traditional public school districts in Indiana. | Source: StatsIndiana.edu

The three school districts in Orange County are Orleans in the north, Paoli in the south and middle, and Springs Valley in the west. These districts experienced a period of consolidation during the 1950s and 1960s, during which numerous schools were combined, including one-room schoolhouses. Now, each district has a single elementary school and one junior-senior high school. The districts range from around 850 to 1,200 students total, which are small enough that it’s hard for kids to get lost in the shuffle, while at the same time large enough for students to receive a well-rounded education.

Orleans has two campuses, whereas Paoli and Springs Valley situate both of their schools on one central campus each. In addition, the Paoli campus also houses the Lost River Career Cooperative, which services several districts by offering career tech classes in construction, health sciences, and other fields. The superintendents of these three districts are Trevor Apple (Springs Valley), Jimmy Ellis (Orleans), and Greg Walker (Paoli).

To meet superintendents Apple, Ellis, and Walker is to realize how closely these districts work together and how effectively they share resources. They meet regularly to discuss the challenges they face as well as strategies and solutions for addressing them. During the COVID-19 pandemic, they worked in coordination, making decisions simultaneously to avoid any public confusion or frustration. As Superintendent Ellis stated, “Having a united front in Orange County with the districts was very helpful during Covid.”

Adverse Childhood Experiences

The three public school districts in Orange County are also part of a resource-sharing coalition called Thrive Orange County, which is anchored by Southern Indiana Community Health Care (SICHC). SICHC describes itself as a faith-driven, nonprofit, community health center. It’s been in the community since 1974 — almost fifty years — and was established when a group of physicians outside of Goshen in northern Indiana set out to help rural communities that lacked health care. SICHC currently has operations in six locations in and around Orange County, and the Thrive initiative is currently directed by Brandy Terrell.

Since its beginning, SICHC has reached outside its clinic walls to support the community. In 2018, the CEO and a physician at SICHC were introduced to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) — a concept that refers to the types of traumatic or environmental events that could threaten a child’s safety and hamper their development. Research on ACEs is usually conducted via simple self-report assessments consisting of a set of questions about ten types of traumatic events — such as sexual abuse, abandonment, and hunger — that could occur during the first eighteen years of a person’s life. An ACE score reflects the extent of the hardships a person encountered during their childhood. Higher scores indicate experiences with relatively more types of trauma (not the amount of trauma) an individual endured before turning 18, which may affect how an individual functions as an adult later in life. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 61 percent of adults in the United States have experienced at least one ACE and 16 percent have experienced four or more types.

Research has revealed that toxic stress from ACEs may affect brain development as well as how the body responds to stress. ACEs have also been linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance misuse in adulthood. Simply put, what happens to you as a child could affect your adult life. For example, some research indicates that an ACE score of 4 is associated with an 11 percent increased likelihood of becoming an alcoholic, a 15 percent increased likelihood of having difficulty holding a job, and a 20 percent increased likelihood of having financial problems.

SICHC initially explored using the ACE questions to investigate obstetrics patients (e.g., pregnant women) in Orange County. Thirty-one percent of the patients scored a 4 or more, which was almost double the national average of 16 percent. Leaders within SICHC wondered, If this is happening to pregnant mothers, what is happening to their children? Consequently, they started talking to key stakeholders and local experts about promoting a culture that reduces the risk of harm to people who experienced trauma and supports their healing and growth, with a focus on children’s well-being. The individuals within SICHC believed such an initiative would be successful because, as one stakeholder said, “the thing that people will get on board for, no matter what their political or religious beliefs, is kids.” In November 2018, the Thrive Orange County coalition was born.

Its website states, Thrive Orange County is a “coalition of community leaders and citizens committed to creating a safe, stable, nurturing community for all.” It consists of community volunteers, local business leaders, faith leaders, medical providers, school employees, and trauma-informed law enforcement agents. The Thrive stakeholders meet in person every couple of weeks. The initiative is data-driven, and researchers, including some from Indiana University, have helped with the data analyses.

Thrive and the Orange County schools

One of Thrive’s first steps was to gather ACE data about children. Thrive approached each of the three school boards for permission to collect data from the students in Orange County. The school boards agreed to incorporate the questionnaire into their curriculum and, along with Thrive, created a detailed plan for data collection. Brandy Terrell, director of Thrive Orange County and parent of a student in Orleans Junior-Senior High School, was impressed that the schools would take such bold steps to get this initiative off the ground. “These schools are amazing,” she said. “They are so forward-thinking and willing to take the risk to do what’s right. The school boards are the change makers and have shown the courage [to change for the better].”

Brandy Terrell, director of Thrive Orange County says, “We really needed to look at the social determinants of health and community as a whole.” | Courtesy photo

Over 18 months beginning in spring 2019, around 85 percent of all 7th- to 12th-graders in Orange County answered the ACE questionnaire. Those that didn’t were either absent or opted out. And just like the pregnant women that SICHC had studied earlier, 30 percent of the children in grades 7 through 12 scored a 4 or more.

Terrell spoke to the seriousness of their findings: “When one sees that 30 percent rate, it’s an alarming figure one cannot ‘unsee.’ … We really needed to look at the social determinants of health and community as a whole.”

Fifty-five percent of Paoli students qualify for free or reduced lunch. Childhood hunger, which is an ACE, is an ever-present issue in Indiana: 47 percent of Indiana’s public school children qualify for free or reduced lunch.

As Paoli Superintendent Walker put it, “If you want to be heartbroken, go on a Monday morning and walk in a school cafeteria for breakfast and see the kids shoveling in the meal because they haven’t had enough to eat over the weekend.”

Since its inception, Thrive has developed a number of initiatives in the community, many of which have involved the Orange County public schools. Through these initiatives, they seek to “help create better students, better employees, and better mommies and daddies.” These initiatives include the implementation of a brain-based social emotional learning program to help kids understand how their brain works and handles feelings, the development of a school-based health model for addressing physical and mental well-being, and Project UNITE — a teen empowerment program to help address teen pregnancy.

A brain-based social emotional learning program

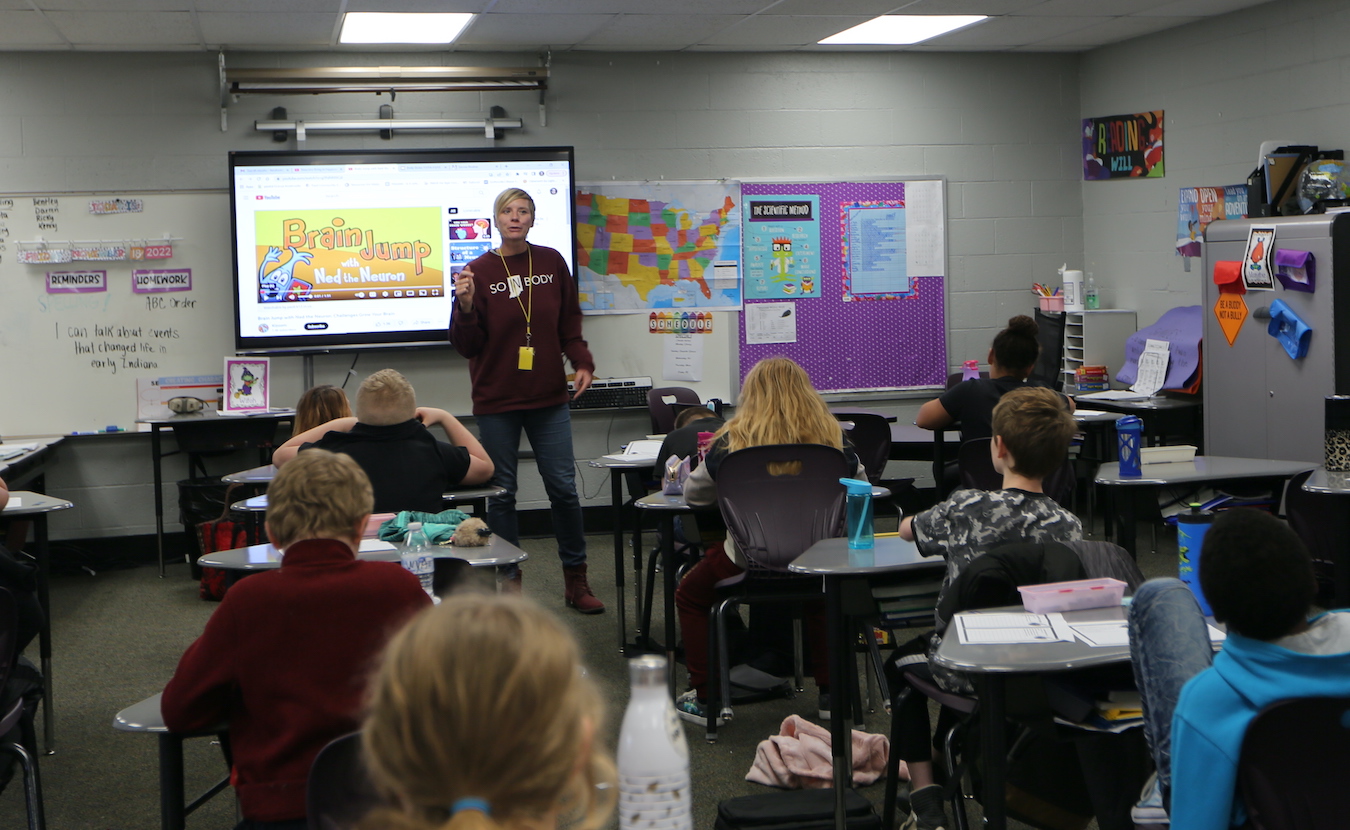

Evidence from the ACE scores pushed Thrive Orange County to ask if more could be done to help support teachers in the schools and provide kids with more access to loving and caring adults and stable environments. Kara Schmidt has been involved with Thrive since its start. Raised in Paoli and trained in yoga and methods for addressing trauma, Schmidt was invited into the schools beginning in 2019. Her work first began in the schools as fairly straightforward yoga instruction but has since transformed into education about the brain and nervous system. She decided that implementing “canned” curricular programs didn’t work, so now she incorporates pedagogical ideas from a variety of sources, adapting them to the specific needs and contexts of the two schools she works in.

The foundation of Schmidt’s curriculum is developing an understanding of the brain. She believes that children can readily grasp sophisticated concepts pertaining to the brain if the concepts are presented in developmentally appropriate ways. Says Schmidt, “Kindergarteners and first-graders know what it means to ‘flip your lid’ [have an emotional reaction]. They know what their amygdala does. They know they have a thinking cap, which is their prefrontal cortex. They know they have a hippopotamus — aka hippocampus. They know these basic concepts.”

Kara Schmidt believes children can readily grasp sophisticated concepts pertaining to the brain if the concepts are presented in developmentally appropriate ways. | Photo by Jennifer Hall

Schmidt builds on those basic concepts in her program to help children develop a sense of emotional awareness and learn how to express their emotions by talking about how they feel. Her teaching also includes focused-attention practices, which could involve aspects of yoga, mindfulness, rhythmic body movements, or deep breathing. In addition, she has incorporated work on the topics of gratitude, generosity, kindness, and compassion. In some classes, Schmidt has instituted a system of “peace pals,” which involves students practicing relating to each other. “Sometimes they get matched up with people they don’t like and they need to learn to be respectful and kind,” said Schmidt. “They need to learn how to get along with them. They don’t need to be friends, but they need to learn how to have a kind and respectful relationship.”

What started in 2019 with just a 1st-grade class for nine weeks, two days a week for 30 minutes each day, has grown. By 2022, Schmidt was in 40 classes, kindergarten through 6th grade, across two elementary schools (Paoli and Orleans) and working throughout the entire school year. By that time she was working with students once a week for 30 minutes. She has also trained an assistant to handle some of the classes. In the future, Schmidt has hopes to expand to Springs Valley but could only do so if she can get another individual to help and the funding to support them.

Since her program began, teachers have noticed a difference in their classrooms. And since Thrive is data-driven, Schmidt is working with faculty at Indiana University and Butler University to develop methods for measuring students’ growth across a school year as well as over the course of their entire schooling from grades K to 12. Going forward, Schmidt and superintendents Ellis and Walker hope to expand her program to explore ways to support and educate teachers about techniques they can integrate into their classes. However, their work with teachers is still in the pilot phase.

The Paoli campus houses the Lost River Career Cooperative, which services several districts by offering career tech classes in construction, health sciences, and other fields. Above, students work on getting their CDL truck driver licenses before graduating high school. | Photo by Faith Gammon

A school-based health model for addressing physical and mental well-being

Thrive Orange County is working with the school districts to offer school-based mental and physical health care on the campuses in all three districts. These districts also work with Youth First, an organization based in Evansville that provides social workers to schools throughout southern Indiana. In Orleans, SICHC helped fund a second social worker in the district so there would be one embedded in their elementary school as well as their junior-senior high school. The other districts would like to add additional support, but qualified social workers are hard to find.

Breanna White (left) is an intern sponsored by Southern Indiana Community Health Care, and Sasha Newland (right) is a social worker at Orleans Jr-Sr High School. | Photo by Jennifer Hall

Social worker Sasha Newland has been serving the Orleans junior-senior high school since 2020. In addition, Newland currently has Breanna White, an SICHC-sponsored intern from Indiana University, working with her. Since both Newland and White are from Orange County, they know the people in the community on a personal level and have an intimate understanding of the problems they face. Their goal is to serve as approachable, caring individuals that students can trust so they might have a chance at mitigating some of the negative effects of ACEs. Being embedded directly in a school building as opposed to a medical office helps them more easily reach the children, teachers, and staff who could benefit from their help. More than 20 percent of the high school population are patients of Newland and White. The Thrive Orange County coalition also provides them with access to funds for coats or groceries that they can give out to high school students in need.

In Paoli and Orleans, SICHC offers telehealth services for students as well. With telehealth, a doctor or nurse practitioner can conduct a virtual examination of a student and provide prescriptions while they are in their school, avoiding the need for a parent or caregiver to pick them up and bring them to a doctor’s office or clinic. Telehealth social worker services are also available in the Paoli schools, which is especially valuable for times when their single social worker is overloaded.

What’s more, a standalone medical clinic will soon be in place on the Orleans Elementary School campus. The clinic will have a sick bay where kids who aren’t feeling well can go to see a doctor or nurse practitioner in person. If medicine is needed, a local pharmacy will deliver it to the clinic and a first dose can be administered with the consent of the parent, but without a need for a parent or caregiver to pick up their child. The clinic will also offer optometry and dental care. When the clinic is operational, its services will be available to students as well as teachers. The ultimate goal is for the clinic to be accessible to the entire community.

Project UNITE — uncovering new initiatives for teen empowerment

Orange County ranks 6th in Indiana for teen pregnancy, which led Terrell, the director of Thrive, to ask “Why are babies having babies?” As data show, high teen pregnancy rates are not good for communities.

“Statistically there is no one who has less [opportunity] than a pregnant teenage mother,” said Chris Lagoni, executive director of Indiana Small and Rural Schools Association. The state teen pregnancy rate is 16.7 per 1,000, and the Orange County rate is 38 per 1,000. White, the social worker described above, who was once a teen mom in Orange County herself, speculated that the high rate “has to do with a lack of resources and access. There is no Planned Parenthood. There is no one giving out condoms in school.” However, she also acknowledged that such resources are controversial in Orange County because of “complicated small-town politics.” Thrive, with the help of the county schools as well as researchers from the IU School of Public Health, established Project UNITE (Uncovering New Initiatives for Teen Empowerment). Their initial goal was to conduct a study to determine why the teen pregnancy rate was so high in Orange County and to use the data they gathered to inform possible solutions to the problem.

Gathering the data for Project UNITE turned out to be much more difficult than gathering data for the previous ACE study. Data collection for this investigation required both students and parents to actively provide consent for participation. In total, 100 interviews were conducted and 108 students completed questionnaires, representing about 12 percent of the eligible student population. Adults who were once teen parents themselves also completed questionnaires. The researchers worked with three of the most prominent faith-based leaders in the community to help reassure people that the intentions of this project were aimed at helping the community and that the project was not about promoting particularly controversial points of view, despite what some might have imagined at first glance. “This isn’t about religion,” Terrell said. “This isn’t about your faith. This isn’t about schools trying to parent your kid or teach sex education. This is about the health of our community. We are sixth out of 92 counties in teenage pregnancy. This is not okay.”

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have been linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance misuse in adulthood.

One of the findings from the study included a need for more and better sexual health education in the community, not necessarily at school. In Indiana, sexual health education is not mandated. If it is taught in a school, the guidelines from the state are not comprehensive. The state only requires that abstinence be taught. In addition, a parent can opt their child out of the program. Participants in the study believe that more education is needed in order to lower the pregnancy rate in the community.

Additional findings of the study included a need for better services for pregnant teens as well as more resources that could be invested to support the young people in the community in general. They recommended that such resources could be used to establish safe spaces for young people to spend their time and special programs that provide goal-setting strategies and access to mentors. Ultimately, Thrive — via Project UNITE — hopes to use the findings of their study to work with community stakeholders and determine methods for lowering the teen pregnancy rate.

Click here or on the image above to watch videos for Orange County by Project UNITE (Uncovering New Initiatives for Teen Empowerment) from the Indiana University School of Public Health.

The impact of the pandemic

Shortly after Thrive launched, the Covid-19 pandemic set in. Although the pandemic may have led to some positive changes, such as people becoming more open to the potential benefits of telehealth and distance learning, there were obviously serious negative effects as well. For example, ask anyone if they believe more kids experienced an ACE (such as hunger) or more of one ACE (such as more frequent physical abuse) during the pandemic and they will, unfortunately, probably nod solemnly in agreement. Paoli’s Superintendent Walker recalled worrying most about whether kids would have enough food to eat during the shutdown. He ended up driving meals to kids’ homes himself because parents could not make it to designated food pick-up spots due to lack of transportation.

“If you want to be heartbroken, go on a Monday morning and walk in a school cafeteria for breakfast and see the kids shoveling in the meal because they haven’t had enough to eat over the weekend.”

Brandi Springer, a Title I teacher (a federally funded teacher to provide extra support in reading or math) at Orleans Elementary School, said that by 2022 “kids (were) a year behind academically and behaviorally.” She also described how difficult it has been for adults to accept the reality of just how far behind the students are as a result of the pandemic. While there is certainly steady learning growth happening in the schools, it’s simply behind where it would have been if there were not a pandemic.

Springer also mentioned that kids are much needier than before the pandemic and that they are demonstrating more behavioral issues. For example, upon returning to school, children have been more apt to speak out of turn and tend to be less able to sit still than before. As such, class size is more important than ever — the increased one-on-one attention that teachers could provide for their students in relatively smaller classes would help to mitigate some of the challenges children are experiencing as a result of the pandemic.

Money, the statehouse, and teacher shortages

One hundred miles north of Orange County, give or take, is where those in power determine the funding available for all public schools in Indiana. The legislators in the statehouse control the “purse strings.” They set property tax caps, which limit the local funds that can be collected to pay for school buildings, sports fields, and buses. The state legislators also determine the classroom funds, which are generated from sales, income, and use tax. Classroom funds are used by school districts to pay teachers and are doled out to each district on a “per child” basis; in other words, in Indiana, the money follows the child. Generally speaking, if a child chooses to transfer to another accredited school, the classroom funds associated with them go to that other school as well. In Indiana, transferring from one public school to another is the largest type of school choice transfer, compared to transferring from public to private voucher schools or charter schools.

Childhood hunger, which is an Adverse Childhood Experience, is an ever-present issue in Indiana: 47 percent of Indiana’s public school children qualify for free or reduced lunch; more than 52 percent of students in Orange County qualify for free or reduced lunch. | Photo by Faith Gammon

Rural public schools in Indiana face especially severe financial challenges. Many are dealing with declining enrollment. For example, in Orange County, the total public school enrollment has fallen by 268 students since 2015 (3,277 to 3,009). Paoli Superintendent Walker is well aware of the financial implications of declining enrollment. “Last year we had 1,240 kids,” he said. “This year we have 1,204, which is a loss of 36 kids. Multiply that by approximately $7,000 per student loss from the state tuition support fund.” The decline in enrollment Walker described amounts to a deficit of around $252,000.

Even with populations shrinking, all three districts in Orange County have benefited from choice in the sense that while some kids transfer out, others transfer in. Students transfer for a variety of reasons, such as a desire to access academic or sports offerings, the location or transportation services of a particular school, or simply because a family is unhappy with their child’s current school. The Orange County district that has benefited from public-to-public school choice transfers the most is Orleans. In the 2022–2023 school year, 191 students transferred in, whereas only 85 transferred out. Bucking the trend for rural districts in Indiana, Orleans is growing. However, their elementary classrooms are also crowded, creating stress for students, teachers, and school administrators. Therefore, the district is drawing from funds generated through bond sales to add six new classrooms to their elementary school in the next school year — an expansion which will also include a special education suite. The hope is that these sorts of investments will encourage families to continue to transfer their children to the school district in the future.

One troubling consequence of inadequate public school funding is teacher shortages. Orleans’ Superintendent Ellis lamented, “The pool of applicants does not exist anymore. We now have two or three applicants instead.” Although all three districts in Orange County were eventually able to fill their open positions this year, it required substantial creative problem-solving. For example, the Orleans district learned that the Spanish teacher in Springs Valley had a sister who also taught Spanish, but lived in Maryland. They set out to recruit the sister for the Spanish teacher position in Orleans, ultimately convincing her to move to Indiana. Prior to recruiting their new Spanish teacher, the Orleans district relied upon Rosetta Stone — a canned, online course — for their Spanish instruction. Moreover, districts are also making “big asks” of retired teachers, hoping they will return and fill temporary gaps. Still, current teachers are concerned. Many teachers in Orange County send their children to the schools they work in and, given the shortage of qualified applicants, they worry about who will teach the youngest children, including their own.

The 2021 legislative session in Indiana resulted in a funding increase for the 2022 and 2023 school years, and the superintendents are grateful for the additional resources that have been provided to them. “I really appreciate the extra funding they put into place [in the 2021] session,” said Ellis. “I fully expected a cut due to the pandemic. If they keep that up, that would be great.”

The statehouse for the 2023 legislative session is also providing an increase in funding for 2024 and 2025 school years, but at the end of the day, despite a record state tax surplus, it will work out to be not as much as the 2021 session for these school districts due to federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Funds (ESSER) expiring in September 2024 and record inflation. Springs Valley Superintendent Apple suggested that the statehouse use the current state budget surplus to return the $300 million that was cut from public education funding during the Great Recession in 2009.

ESSER has served as a substantial resource for the Orange County schools, pumping in millions of dollars into the districts. All three districts used those funds to put extra staff in place, although they will need to rely on funding from the state to pay their salaries once the ESSER funding runs out. The ESSER funds were also used to pay for material goods such as career tech equipment and new boilers at Springs Valley.

A class at Springs Valley Jr-Sr High School. | Photo by Alayna Denbo

Recent cost increases due to inflation have also been an issue for schools. For example, Paoli purchased new buses last year for $92,000. If they had to purchase them today, those same buses would cost $130,000. Two years ago, mini buses were $52,000, and they are now $87,500. In Paoli, teachers were given a $5,000 pay increase thanks to the tuition support funding increase. That raise was more than the raises from the previous nine years combined. It moved the minimum salary to $40,000, but other districts that already paid more are moving to even higher amounts, too. Speaking to the challenges schools face when trying to offer competitive teacher salaries, Walker said, “You try to catch up, but you can’t.”

On top of the standard public school funding issues, funding for the Thrive efforts in the public schools is complicated. While larger districts may have funds for positions such as a director of behavioral learning, small rural schools typically work with relatively small budgets. As a result, special initiatives that rural schools wish to institute are more often funded through short-term cash sources such as grants, ESSER funds, and private donations. Funds that may be available one year may not be available the next.

For example, in order to run Kara Schmidt’s social emotional learning program this year, the Orange County schools had to apply ESSER funding and rely on funds from a private donor. “It is incredibly stressful,” says Schmidt, who also had a grant fall through at the last minute. In addition, the social workers Orange County currently employs are paid in part through ESSER funds, grants, SICHC, Youth First, and other temporary funding sources. Ultimately, the hope is to identify a consistent funding source that is substantial enough to support more social workers as well as an on-site health clinic.

The financial challenges public schools face in places like Orange County can leave community members and stakeholders feeling as though politicians don’t care much about rural communities. “We feel pretty forgotten, which is why we are doing these things ourselves,” said Schmidt. “I don’t think the state understands that these kids are human beings. We need to see them and respect them as people.” One child told Schmidt and his classmates during one of their gratitude activities, for example, that he was grateful that his parents could give him a bath. “Baths and clean clothes are huge things for some kids,” Schmidt said.

Achieving system change takes time

Improving a community doesn’t happen overnight and Thrive is a young program. The success so far for the Thrive Orange County coalition has been the creation of a strong foundation to help implement systemic community change. Key to Thrive’s foundation and continued existence is the presence of a support agency — SICHC — and a salaried director to oversee the variety of moving pieces that are necessary for the coalition to function. The key stakeholders are residents who reside in the community. While the community may not immediately see the impact of the Thrive initiatives — lowering ACE scores, lowering the pregnancy rate, and more — they will see them a generation from now.

Key to Thrive are the public schools, as they are the heart of the communities in Orange County. Not only are community public schools where children are educated and home to traditions such as football and marching band, they also provide basic human needs for children. Meeting basic needs is not new to public schools. But the number of needs and challenges have expanded over the years and so this public school and community health partnership is a step in the right direction.

Help kids — who will eventually be adult community members — where they are easiest to reach. Essential to caring for Orange County’s children is healthy and stable funding to run the schools and attract amazing teachers to educate them as well as fund the health-care providers to care for them.

Speaking about the overall impact of the Thrive Orange County coalition, Superintendent Walker said, “I can’t imagine life without them.”