Caring for gardens increases our understanding of the interdependence of our natural environment with our own well-being. Fluctuating temperatures, periodic drought, and the onslaught of heat are all stresses that test the resilience of your landscape and garden plants. It doesn’t matter if the plants are trees, shrubs, vines, and other perennials or annual flowers and vegetable gardens, they are all influenced by changing weather patterns. To create the beauty or desired productivity, we must look to create a healthier and more resilient environment for our plants and for us.

Garden types and styles can range from forest gardens and edible landscapes to kitchen gardens, cottage gardens, and the more traditional American yard with flower beds. Each type or style may have a different purpose or role to play for your home and landscape. Yet all bend to the will and strength of Mother Nature to a greater or lesser degree. Recognizing the imperative to work with forces greater than us comes through understanding the basic environmental limiting factors of sunlight, water, and soil.

Sunlight and heat

Heat stress can reduce growth and stop production of plants that produce fruits, such as tomatoes, Scholl says. These Rutgers tomatoes, however, have yellow shoulders and will not fully ripen due to a potassium deficiency, which a soil test would have detected. | Photo by Jami Scholl

Sunlight is necessary for photosynthesis, yet some plants require little or indirect light, while others need at least six hours or more. A factor many may not consider when thinking about specific plant light needs is the intensity of heat created. Even though a plant description may say it needs full sun, there can be times that intense sunlight can cause heat stress.

When growing annual food plants that produce fruits, such as our beloved tomato, heat stress can greatly reduce growth and completely stop production. A large juicy beefsteak will be more affected than the smallest of the family, the cherry tomato, yet all are affected. Using the Fahrenheit scale of measurement, growth slows when daytime temperatures rise above 85° F, and when the temperature reaches 95° F growth stops completely. Simply, the plant cannot function in such high temperatures. And if nighttime temperatures do not drop below 70° F, especially after such hot days, then you can expect blossoms to drop and all production to cease until the plant is out of survival mode.

Heat stress can be seen in trees first by droopy or wilty leaves. As the heat continues, branches may droop, inner leaves or needles may turn yellow, and the edges of leaves may look scorched. The tree may also look sparse as new growth stops or doesn’t start. This is caused by the tree losing water faster than it can be replaced. As the stress continues, leaves may drop and sap may ooze from the trunk, attracting insects such as ants or beetles. These visual indicators will occur when the air is more dry than humid, although if prolonged days and nights of high temperatures continue, then trees, and all plants, suffer.

Growing zones

The hardiness zones in Indiana have shifted in the past few decades. Bloomington was in zone 5 prior to 2012 but is now in zone 6a. | Source: planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/

Landscape plantings, like those that produce fruits and vegetables, are best chosen by light and water needs, as well as temperature. This is called a plant hardiness or growing zone. Hardiness zones are based on the average annual minimum winter temperature, and broken down to 10 degree increments. The coldest temperature from each year between 1976 and 2005 is used to calculate the average temperature. This number is then used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to determine the plant hardiness zones of the United States.

According to the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone map, the Bloomington area is zone 6a. Most of the northern part of the state is in zone 5b, with the extreme southern part of the state in zone 6b. Some may think this is only applicable to annuals and vegetable growing, but it also needs to be considered for herbs, native plantings, and fruit production. The Plant Hardiness Zone Map is a good resource to quickly know what plants will do the best where you live. The map was updated in 2012, but prior to this time the Bloomington area was classified as being in zone 5. The National Arbor Day Foundation has an animated map where the viewer can see these changes. Since trees and shrubs are long-term investments, taking into consideration how the zones have changed, and are predicted to change, will help you select the species and variety best suited to our local environment.

Chilling hours and erratic bud break

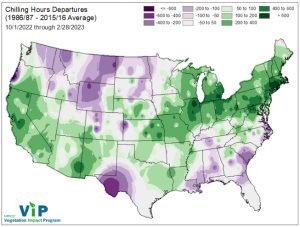

Should you consider adding fruit trees to your landscape, whether that is in the form of a more decorative espalier (fruiting or ornamental plants trained by supports and pruning to grow flat against a wall or trellis system) or in a more natural form such as an edible forest garden, it’s imperative to know how many chilling hours are needed for the tree to set fruit. Maps by the Midwestern Regional Climate Center’s Vegetation Impact Program (VIP) provide a reference for the number of chilling hours, which are tracked from between October 1 and the end of February.

Whether you choose a decorative espalier (above) or a more natural edible forest garden, it is essential to know how many chilling hours are needed for a tree to set fruit. | Photo by Jami Scholl

Chilling hours are the average number of hours, or a range of hours, when air temperature is between 32° and 45° F during the winter season that are needed for normal tree development. If a tree doesn’t receive enough chilling hours, bud break and flowering in the spring is erratic. One VIP map, “Chilling Hours Departure,” shows that from 1986 to 2016 the number of chilling hours fell by a range of 200 to 400 hours per winter. By also referring to the graph “Chilling Hours in Indianapolis” on the Indiana State Climate Office website, we can determine that the below-average number of chilling hours has declined over time.

For Bloomington, this is a significant change that affects apple fruit set, which has had local repercussions. Longtime locals reflect fondly about the complexity and unique flavor of the local apple cider in the 1990s and earlier, compared to the cider produced today. Red Delicious apples were one of the varieties grown here in the 1980s and used in the production of a sweeter apple cider. According to the National Arbor Day Foundation, the Red Delicious apple requires 700 to 800 chilling hours, and therefore the lower number of chilling hours is no longer as favorable to growing the Red Delicious variety in our area.

By choosing varieties with a lower number of chilling hours needed for proper fruit development, you’ll be better set for a continued harvest into the future. Some varieties that currently fit this criteria include Liberty, a disease-resistant, all-purpose variety developed in the United States; Pristine, a disease-resistant and flavorful variety developed in France; and Monty’s Surprise, a new and extremely healthful introduction to the U.S., originating from a wild apple tree from New Zealand.

Frost days and grafted apple trees

Chilling hours are the average number of hours, or a range of hours, when air temperature is between 32° and 45° F during the winter season. These chilling hours are needed for normal tree development. From 1986 to 2016 the number of chilling hours fell by a range of 200 to 400 hours (about 8 to 16 days) per winter in most of Indiana. | Source mrcc.purdue.edu/VIP/indexChillHours.html

Purchased apple trees typically have been grafted to assure that you are purchasing trees that produce fruit with reliable flavors and texture. Grafting is when branches are cut from the original tree at the time of winter pruning. These cuttings are then grafted onto a specially selected rootstock by matching the cut of the branch (scion) to that of the rootstock and by matching the angle of the cuts to align the cambium (the green living tissue immediately below tree bark), and then by binding the scion to the rootstock for them to fuse. Each rootstock allows for better control of size and hardiness to low temperatures. The branch from the original tree allows the fruit to stay true to type. When an apple reproduces from seed, the resulting fruit from the child tree will not be the same as the parent. Just as human children are all different from one another, apple fruits are each different in flavor, texture, color, and more, from the parent trees. Thus, the only way that an apple continues to produce the same desired fruit is to propagate it by grafting.

Chilling hours are necessary to fruit trees since the number of chilling hours trigger the plant to express specific genes for metabolism necessary to reproductive processes, according to a report published in Nature. The timing of the tree being released from dormancy by its genes determines its ability to begin developing fruit after its embryonic stage. This occurs during bud break, or when new buds begin to open.

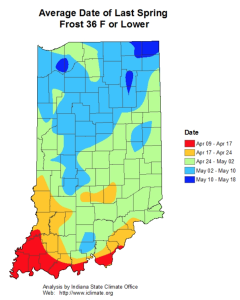

Frost dates are important to know for when to plant flowers, vegetables, and tender herbs outside, and how late they’ll grow into the autumn. The last frost date of 36° F or lower for Monroe County could be anywhere from April 17 to May 10. | Source Indiana State Climate Office

Frost dates are important to know for when to plant flowers, vegetables, and tender herbs outside, and how late they’ll grow into the autumn. The beauty and habitat benefits that annuals provide to the garden and landscape cannot be replaced by perennials. Neither can tomatoes, peppers, and many other typical garden plants. The frost date is when the air temperature falls below 36° F, 32° F, and 28° F or lower, as some plants are more tender and will die at 36° F, and others at 32° F, and yet others will succumb at 28° F unless protected in some way. The estimated last frost dates for these temperatures can be found on the Purdue University freeze/frost probability maps.

Water, droughts, and rainfall timing

Much like sunlight, water needs can be thought about as the overall amount and duration of rainfall. The average annual amount of precipitation for Bloomington is 47.32 inches, according to usclimatedata.com. Lucky for us, precipitation that falls in our area is spread out over the year. Although there have been times when large amounts of rain fall in a short amount of time, with a potential to cause flooding, there are also years where weeks stretch into months with no rain, causing a drought situation. Drought is when the amount of precipitation, a combination of rainfall and snowpack, needed to meet local needs for water isn’t adequate. By caring for the soil, normal rainfall is absorbed into the soil instead of running off into a drain or ditch, taking nutrients with it.

There is another consideration for newer gardeners in regard to water, and that is the pressure behind the water being applied to plantings. Similar to a downpour that generates runoff, even on the best soils, the power behind a water hose can move soil, exposing newly planted seeds or laying bare the roots of newly planted trees and shrubs.

Growth of food plants slows when daytime temperatures rise above 85° F, and when the temperature reaches 95° F growth stops completely.

Allowing for enough time to water young or newly planted vegetables, herbs, shrubs, vines, and trees appropriately — rather than blasting them with a powerful stream of water to get the chore completed — will support the plants in your garden. Instead, use a nozzle with a mist setting for the earliest seedlings, and a setting that mimics rainfall to disperse and moderate the force of water. You might also consider temporary or permanent drip irrigation. Soaker hoses are temporary, with plastic pipe used in a permanent system designed specifically to move water, under low pressure, to plants. This method of watering greatly reduces evaporative loss while also protecting plant leaves and roots, as well as preventing runoff.

Living soils

Chilling hours trigger fruit trees to express specific genes for metabolism necessary to reproductive processes. This occurs during bud break, or when new buds begin to open, as on this crab apple bud swell. | Photo by Jami Scholl

Soil is much more than dirt. It is a world that’s still being discovered, consisting of mycorrhizae, or fungal roots that have a symbiotic relationship with many plants and fungi in soil. Their role in the ecosystem is to grow to a greater distance than that which a plant’s roots can grow, allowing them to access water and nutrients and then transferring this to the plant roots they touch. This enhances the health of every plant it touches, while also bringing carbon from the plants to fungi in the soil.

The existence and function of mycorrhizae in an ecosystem is vital to the resilience and well-being of the entire system. Soil with good water-holding capacity can help protect your plants against heat stress by easily absorbing and retaining greater amounts of water.

Sandy and hardpan soils

Soil has the power to retain or repel water, as can be seen in sandy and clay soils. Soils that are predominantly sandy lose both moisture and nutrients more easily. In contrast, soils that are too heavy in clay may have more nutrients but they can become hardpan, where water hits the surface and runs off before it can be absorbed. Rock, a steep slope, and large amounts of clay can either manifest or kill dreams of your ideal garden, no matter what type or style you envision. Leaves, branches, mulch, wood chips, and even fallen trees, when allowed to decompose, build the soil and prevent evaporative loss.

Soils that are heavy in clay may have more nutrients, but they can also become hardpan, where water hits the surface and runs off before it can be absorbed. | Photo by Jami Scholl

The power of a well-balanced living soil cannot be overstated. A regular soil test will give you the results of soil pH, organic matter levels, and the amount of nutrients, yet having the most resilient soil goes beyond what the typical soil test measures. Soil tests can be ordered from Monroe County Soil and Water Conservation District, A&L Great Lakes Laboratories, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Low- or no-dig methods

Many urban and suburban parcels have been bulldozed, removing the top soil when a housing development is created. This often leaves a heavy red clay behind, creating hardpan for the new homeowner. By using no- or low-dig methods for installation of annual garden plants, you’ll help build the nutrient cycling (a cyclical process that moves nutrients in the environment to plants and fungi, and then back to the environment), increase water retention, and eliminate the need for synthetic fertilizers. As for trees, reflect upon the ideal habitat, a forest, noting what plants grow near one another and how the soil is built.

Toward resilience and beauty

Improving the ability of plants to adapt and recover from difficult growing conditions is key to continuing to enjoy the beauty and health-providing sustenance of your garden. When selecting plants, especially trees, a much longer view into the future is needed to choose the type and variety best suited to your specific location. The waterfall amounts, heat, and droughts have all been an ongoing stress to the white pine. To consider other evergreen trees that can tolerate the conditions of 10, 50, or 100 years or more can give us another view of the future. One that is more than a year or two away. The pinyon pine, although not native to Indiana, is native to the U.S. It is deer resistant, attractive, tolerant of droughts, and grows in zones 4 through 8.

After facing the onslaught of heat, drought, fluctuating temperatures, major storms, and flooding, the plants that compose your garden will be better able to retain beauty throughout the year when carefully selected with an eye to soil and water needs. Gardens can provide you with a beautiful landscape as well as an abundance of tasty and healthful foods.

Our wellness is mutually dependent on the health and resilience of our gardens; may we care for them with compassion and understanding.

The incredibly edible tomato. | Limestone Post