Our built environment is much more than concrete and glass; it’s our political climate, our social reality, and our emotional landscape. At a time in American life when history and image are used to construct selective realities of a golden era through a red MAGA hat or to demand steadfast change with an upheld fist and a homemade sign that reads “Say Her Name,” the tension between fiction and utopia is taut. Possibly too tight. Possibly not tight enough.

‘Paper Pavilions’ features the commissioned work of Midwestern artists from October 1 through November 21. | Photo by Ian Carstens

Paper Pavilions, a group show of commissioned works by Midwestern artists, implores for a conversation in relation to key architectural and natural sites in southern Indiana. The exhibition is currently up physically and virtually at 411 Gallery in Columbus, Indiana, from October 1 through November 21, and asks for artist and audience to consider “during a global pandemic and a widespread call for dismantling racist systems, the future of our built and natural environment.” Curated by Sean Starowitz, the City of Bloomington’s assistant director for the arts, it features the work of Gnat Bowden, Carlson Garcia, Samuel Levi Jones, Rachel Kavathe, Claire Krüeger, Maddie Miller, Armando Minjarez, Joann Quiñones, and Andréa Stanislav. The exhibition is a patchwork of partnerships and support from the Bloomington Entertainment & Arts District, Sycamore Land Trust, Columbus Area Arts Council, Columbus Museum of Art & Design, ArtsRoad 46, Indiana Arts Commission, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

The legacy of the interplay between humans and their built and natural environments goes back to whenever you wish to consider the “beginning” to be. Starowitz situates Paper Pavilions more contemporarily with Penelope Curtis’s work on the relationship of sculpture and architecture, the interventionist desert exhibitions of Noah Purifoy, and the works of Gerrit Reitveld, Maya Lin, Isamu Noguchi, and Étienne-Louis Boullée. Art biennales, which provide site and culturally specific opportunities for the exhibition of public art, such as Columbus’s Exhibit Columbus, only touch the surface of the possibilities of the public art experience.

Originally a three-city project (Bloomington, Indianapolis, and Columbus), Paper Pavilions pivoted over the course of two years following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, as well as the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the modernist model, Starowitz says, “you cannot divorce nature and race, in this moment that we are in, with regard to art.” As the work came in and Starowitz worked with the artists, the exhibition evolved into a show equally about establishing a “vocabulary of public art,” says Starowitz, while maintaining the paradigm shift with regard to pavilions and bienniales. Whereas sculpture has normally placated itself to the interest of architects, spatial designers, and financiers, Paper Pavilions seeks to provide artists with the opportunity to set the tone for the future of public art in their communities. A shuffle of our current moment, Paper Pavilions oscillates tonally and aesthetically, reminding me of the multi-genre POLLEN Spotify playlist. Works in this show are models or proposals, all with a degree of the conceptual and the actual. The end result is much like a science fair with nuanced art models instead of baking soda volcanoes, but with the same possibility for wonder.

Some pieces yearned for the public’s interaction to break out of the confines of their model, such as Andréa Stanislav’s Three Tribunes for a Long Century. A proposal for three migratory tribunes or towers with billboard-size LED screens on the top that display questions and messages such as “Next?” or “Stand Out.” When installed, these towers would establish a triangle with their three Indiana locations. As viewers look at the model, one can imagine being washed in LED light, as people speak out from a tall, chrome tower. But to feel this would be something much more than a simple daydream. Reference to a historical context of the constructivists, to the Columbus Mill Race Park lookout tower, and to the significance of platforms for dialogue make its potential installation all the more timely.

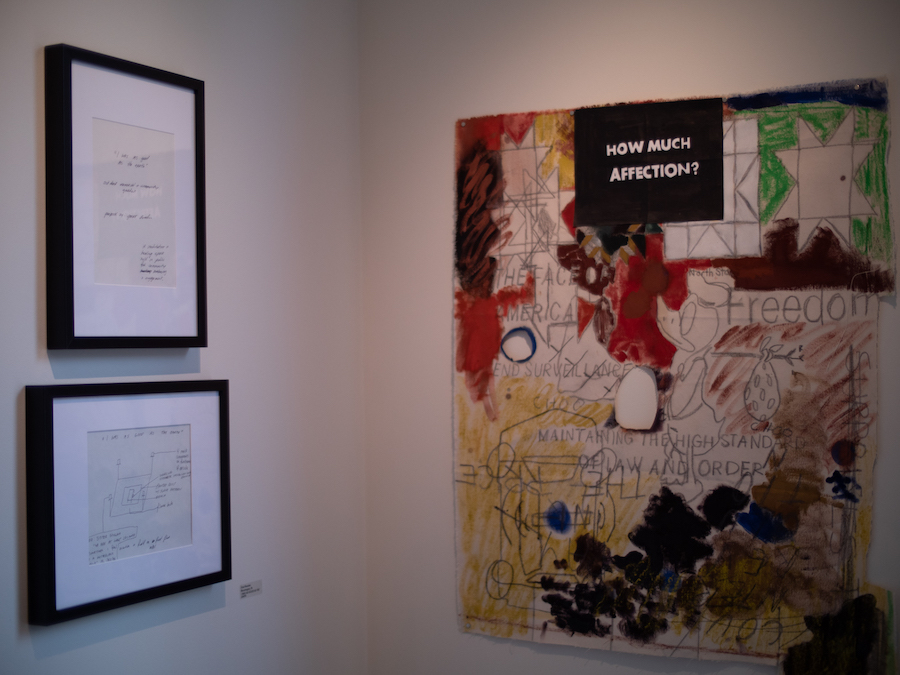

While Stanislav’s work references modern political abstractions, Gnat Bowden’s piece challenges the personal in I WAS AS GOOD AS THE EARTH. In a proposal that considers systems of violence, documented in two drawings and a quilt-like painting, Bowden has created the blueprints for reconciliation and redemption. Reminiscent of Ai Wei Wei’s piece Remembering, which included 9,000 children’s backpacks installed outside the Haus der Kunst in Munich, I WAS AS GOOD AS THE EARTH ignores niceties that complicate the lived experiences and trauma of public, social, and psychic realms. Bowden’s work feels torn straight from their sketchbook, pulling our American structures and subconscious with it.

Rachel Kavathe’s three-image documentation and small-scale modeling, Monument to Change, is one of the works in this show that reminds me most of a field trip to the science museum. This eco-revelatory design and land-art proposal draws attention to the Sycamore Land Trust’s Touch the Earth Natural Area in Bartholomew County. On an even more intimate level, the small-scale, limestone-disc models showcase how life can grow on the same stones our nation uses to build our idols and symbols, reminding us that even our symbolizing is subject to nature. I can’t help but recall Jeff Goldblum’s meme-able statement from Jurassic Park that “life finds a way.” Arguably the only “living” piece in the exhibition, Kavathe’s work expands the parameters of how Paper Pavilions and public art can be understood, as concepts and material that derive from natural sources.

Similar to the time-based nature of Kavathe’s work, Claire Krüeger’s video/sculpture Going Down further explores the transitory nature of human interventions, particularly our monuments in the natural ecosystem. Video is a medium that is often passed over for sculptural and architectural pavilions, according to Starowitz. Going Down features a campy treatment of monument decomposition by fungi, which were collected on hikes throughout the Touch the Earth locations. This approximately two-minute looping video was conceived, in one rendition, to be projected onto various sites of key modernist architecture in Columbus. Krüeger’s work showcases a simple but profound fact that the built environment is a part of a much larger environment, one that feels the movement of time and natural forces.

In a tone similar to Krüeger’s video piece, which concludes with footage of a frog winking, Mutant Bower, the work of the Carlson Garcia collective, brings the activity of building an environment to the front of the senses. The physical model for Mutant Bower, a proposal for the Sycamore Land Trust nature areas, features wooden sculptural pieces that feel akin to Ikea baby toys atop a layer of Astroturf, with a sound component (which when installed would exist inside the sculptures). Like Kavathe’s work, this piece pulls on the wonder of childhood experience, reminding me of how vibrant the forest felt as a kid, and how quiet it feels now. There are also two manipulated photographs that showcase the structures in natural settings. While these combined pieces do bring to mind sculptures built for an LSD-tripping Burning Man crowd, they speak to a significant gap in Western belief systems about the inter-shaping of humans and nature.

The interconnections of people and nature are captured outright in Joann Quiñones’s work From Around Here. The only figuratively representational work in the show (with the exception of a fist in Samuel Levi Jones’s work), Quiñones’sFrom Around Here features pictorial portraits of Hoosiers collaged in their “natural habitat” at the Touch the Earth preserve. Responding to common questions such as “Where are you from,” “Who is a local,’’ and “What is an invasive species,” Quiñones’s work balances context with critique, celebration with consideration. Like Bowden’s work, From Around Here directly connects built systems to bodies, particularly Black, Brown, Indigenous, and LGTBQ+ bodies. Bowden’s quote about their work applies to Quiñones’s work as well, “that Black bodies are less protected than natural ones,” which brings to mind the attempted lynching of Bloomingtonian Vauhxx Rush Booker at Lake Monroe this summer. In connection with this statement, From Around Here feels like a memorial as much a document.

Similarly, Maddie Miller’s three pieces, Floor 1, Floor 2, and Attic, document current injustice through sculptures that freeze time-based experiences, almost memorializing them. Using concrete, Miller’s work is reminiscent of Greek, Byzantine, and Roman architecture (the Roman’s having invented concrete), while also referencing the mnemonic system of “method of loci,” also known as a memory palace. On first glance, Miller’s Floor 1 and Floor 2 bring to mind childhood hijinks of writing your name in a freshly poured sidewalk, but on closer inspection they soberly showcase floor plans of evicted homes. These two pieces, along with Miller’s Attic (a miniaturized casting of the top floor of a building), highlight the painfully recent shelter-in-place orders of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the timeless connections of home.

Using accumulated time and the items that hold it, Samuel Levi Jones’s Still Rising piece features an iconic black fist surrounded by a multicolored, quilted background made up of law books, some that were donated to Levi Jones by the City of Bloomington. Drawing attention to the materiality of law and the systems in which it exists, Levi Jones reminds us that what we do with truth and how we treat knowledge are all built structures. As the black fist establishes itself firmly in the middle of the various book covers, it holds a relevant gesture with a lineage tied to the Black power, civil rights, and arts movements, iconically raised by Tommie Smith and John Carlos during the medal ceremony in the 1968 Olympics, and seen in our streets today with the Black Lives Matter protests for dismantling racist systems. A list of the connections that Levi Jones’s Still Rising elicits is long — the title nods to the significant work of Tupac Shakur, Maya Angelo, and Lewis Hamilton. Still Rising confidently showcases the seams of each stitch, showing us how our built environment is first and foremost “built.”

Working with similar themes of critique of displacement and fostering empowerment, Armando Minjarez’s Technotitlan gives endless space to the potential of the future. A technicolor image of an imagined plaza, featuring all handmade objects, Technotitlan pulls on tedious research of the history of the Mexican quiosco (kiosk), while embracing potentiality with a freedom galactical in scope. While on one level this piece is similar to Stanislav’s Three Tribunes for a Long Century in its conceptual futurism, there is something personally approachable about Minjarez’s work, the type of abandon one feels with a dream. As a white, male writer I can’t help but feel that the intricacy and beauty that Technotitlan offers may not be for me, or not even for my comprehension. And why should it?

(l-r) ‘Monument to Change’ by Rachel Kavathe, ‘Floor 2’ by Maddie Miller, and ‘Still Rising’ by Samuel Levi Jones | Photos by Ian Carstens

Paper Pavilions maintains a level of transparency and interdependency that makes for a refreshing artistic experience while providing a watering hole for a variety of artists and craftspeople. These new forms of alternative exhibition have a history as well, fitting in a trajectory of Cassiano dal Pozzo’s “Paper Museum,” Marcel Duchamp’s “de ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (La Boîte-en-valise)” and “Boîte surréaliste.” Apart from the exhibited artists and work of the curator, Paper Pavilions is made real in digital spaces through a website designed with Bauhaus-like finesse by Emily Miles, a virtual reality tour by Tony Vasquez in collaboration with Echo Bravo that takes me back to my Architectural Digest “Open Door” video binge from earlier in the pandemic, and an upcoming essay by Danicia Monét. A post-exhibition publication will assemble the works and ideas into an archived printed space. And on October 21, a panel discussion will be held with Paper Pavilions artists Claire Krüeger and Rachel Kavathe in a conversation with Abby Henkel of Sycamore Land Trust.

“Our country is still relatively new with regard to its identity, and the realm of public art is very new still, arguably the last 50 years,” Starowitz says. “But what we’ve seen sweep across small-town America and mid-sized cities is the importance of place.” Like the resilience of a handful of sticks compared to a lonely twig, the vibrancy of various modes of accessibility for the exhibition not only highlights a creative response to the COVID-19 pandemic and calls for dismantling racist systems, but it also showcases the various pathways to visualization. Esteban Garcia Bravo of the Carlson Garcia collective spoke of their process with Paper Pavilions to be that of reconnection, of “coming back to center.” However you choose to approach this exhibition — physically or virtually, contextually or aesthetically — consider your future changed.

Paper Pavilions

411 Gallery

411 6th St.

Columbus, Indiana

October 1–November 21, 2020

Open Hours: Fridays 12 p.m.–4 p.m. Limited to 4 guests at a time. Masks required.

By appointment contact: Susana Villegas, svillegas@artsincolumbus.org

View the virtual exhibition here.

Watch a panel discussion on October 21 at 5:30 p.m. EDT with Paper Pavilions artists Claire Krüeger and Rachel Kavathe in a conversation with Abby Henkel of Sycamore Land Trust. A recording of the event will be available at the link above.