When I try to think about expectations for perfect verse, I instead end up lost and awash with questions. Like, is it the responsibility of poetry to communicate more than common language or to do just enough — to communicate something urgent? What are the experiential differences between a voice and printed text? Why have I identified with some forms of poetry, but felt excluded from others? What’s meant and not meant for me? Is it better to pursue great truths or write sincerely on the mundane? Who decides if a poem is remarkable, pedestrian, pedantic, “posthuman,” cool, trendy, authentic, bad? I think what’s at heart here is the impossibility of getting at the heart at all. I can’t figure out what makes a perfect poem.

The spring I graduated from Indiana University with a degree in creative writing, Harper’s Magazine published the article “Poetry Slam, or the decline of American verse.” At stake for Mark Edmundson, the article’s author, are a handful of unfortunate contemporary trends that have failed to carry on the legacy of so many masters. He cites Lowell, Emerson, Dante, and Melvin, among other pre-21st century elites. Voice, he claims, is central to the decline; uniqueness, the vain new conquest. He says contemporary poets don’t care about the “attempt to imagine a posthuman identity,” which he calls the project of a poem. Contemporary poets are not bold enough, always backing away from capturing some depth of man’s essence. They bare their personal histories, which moor them to their messy, trivial selves — to each her own piddly moment in the sun.

Adrian Matejka, a recent Pulitzer and National Book Award finalist and an associate professor of creative writing at IU. | Photo by Ryan Brady-Toomey

Judging by his choice of poets, the author stands by conventions of art that have historically insulated the so-called literary canon. If I remember my Modernist lit classes well enough, disciples of the Classics and Modernists, like Edmundson, forever painstakingly tend the precious fire of hope that poetry and art can be made perfect. A poem can be classic, timeless, questionless, scrubbed clean of the maker’s cultural identity, nearer, then, to a more perfect and ethereal truth, emerging as a fully consummate form as if born from the forehead of the universe itself. A poem can be evidence of the possibility of Utopia. Like an Eames chair or Ikea.

I don’t buy it though. I can’t afford to. “It has always seemed awkward that I had to take classes, publish in journals, go to an MFA program, and publish a book to be considered a ‘literary poet,’” writes Adrian Matejka, recent Pulitzer and National Book Award finalist and an associate professor of creative writing at IU. “That assumes a great deal of privilege — that I can afford more classes (I can’t — student loans), stay jobless for three years to get an MFA (can’t do that either — more student loans), then figure out how to eat while I work on a book and have to pay back those loans.”

Like a gritty open wound, Edmundson’s piece fascinates me because it so boldly exposes deep rifts that divide the poetry community — rifts that have real consequences on who is included, funded, validated, and remembered. Evidenced by his title, “Poetry Slam” (though, oddly, poetry slams are never discussed in the article), Edmundson outright dismisses an enormous tradition of poetry that is entirely concerned with voicing — aloud, together — experiences that challenge traditional beliefs about art, body politics, and equal access.

Page versus stage

There are two meaty poetic categories brought up directly (or incidentally) by Edmundson, which opens up this whole mess. Between them there appears to be a simple binary difference, but I believe below the surface there is a murk of ideas and expectations that go far deeper than form. It’s what people have called “page vs. stage” poetry.

Generally a poem is considered “page poetry” if it gains strength from its positioning on a fixed surface, such as paper or a screen. The fixed surface allows the reader an infinite amount of time to explicate the poem, which permits the poem to be infinitely complex and rich. “Stage poetry” depends on its oral delivery. The performance denies the piece a static form, exerting it instead as a terminable experience. If the words are written down, there is a sense that the page is only a memory object and not really where the poem resides.

Poet Alexandria Hollett performs “Blessed Are The Persecuted: An Open Letter To The Indiana Legislature” at a protest of the passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 2015. | Courtesy photo

But these terms are like fraternal twins. It’s unlikely to hear one spoken of without the other. This piece is great read aloud, but less interesting on the page is a common phrase in a poetry workshop. There’s almost always an additional sense of tension elbowed in — an expectation. Surely, a poem can be as moving performed aloud as silently read. But what does perfect balance comprise? What are our requirements of a poem? What do they say about us?

In the spring of 2015, Alexandria Hollett, a poet living in Bloomington, wrote “Blessed Are The Persecuted: An Open Letter To The Indiana Legislature.” She performed the poem to about 200 people protesting the passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. It was her first spoken word poem. Hollett says she’s pursued poetry for the past two decades, but it was only in recent years that she fell for spoken word. “I likely would have loved it sooner,” she writes to me, “but I wasn’t exposed to spoken word and slam artists … until I started to interrogate big questions related to (in)justice and (disem)power(ment) — questions that elements of slam and spoken word seem uniquely positioned to address.”

In the late 1980s, poetry slams began as an alternative effort to de-establish the perceived polite, academic protocol of traditional poetry readings. Rooted in the same antiestablishment politics, slam has been deeply influenced by the 1960s and ’70s spoken word movement. Performed competitively, slam poems are three minutes in length. Out of this constraint, slam has additionally developed rhythms, cadences, and structural characteristics that feel unique to the genre. On this form, Hollett says:

“I think that slam and spoken word force me specifically (because not everyone cares about this) to think carefully about the narrative as well as the ‘art’ of it all — I really hate sitting through poems that sound like a bunch of word soup. … I only have three minutes to get my point across — the audience doesn’t get to read along or return to it to figure it out later — and I appreciate the urgency and clarity that that ‘constraint’ lends to my work.”

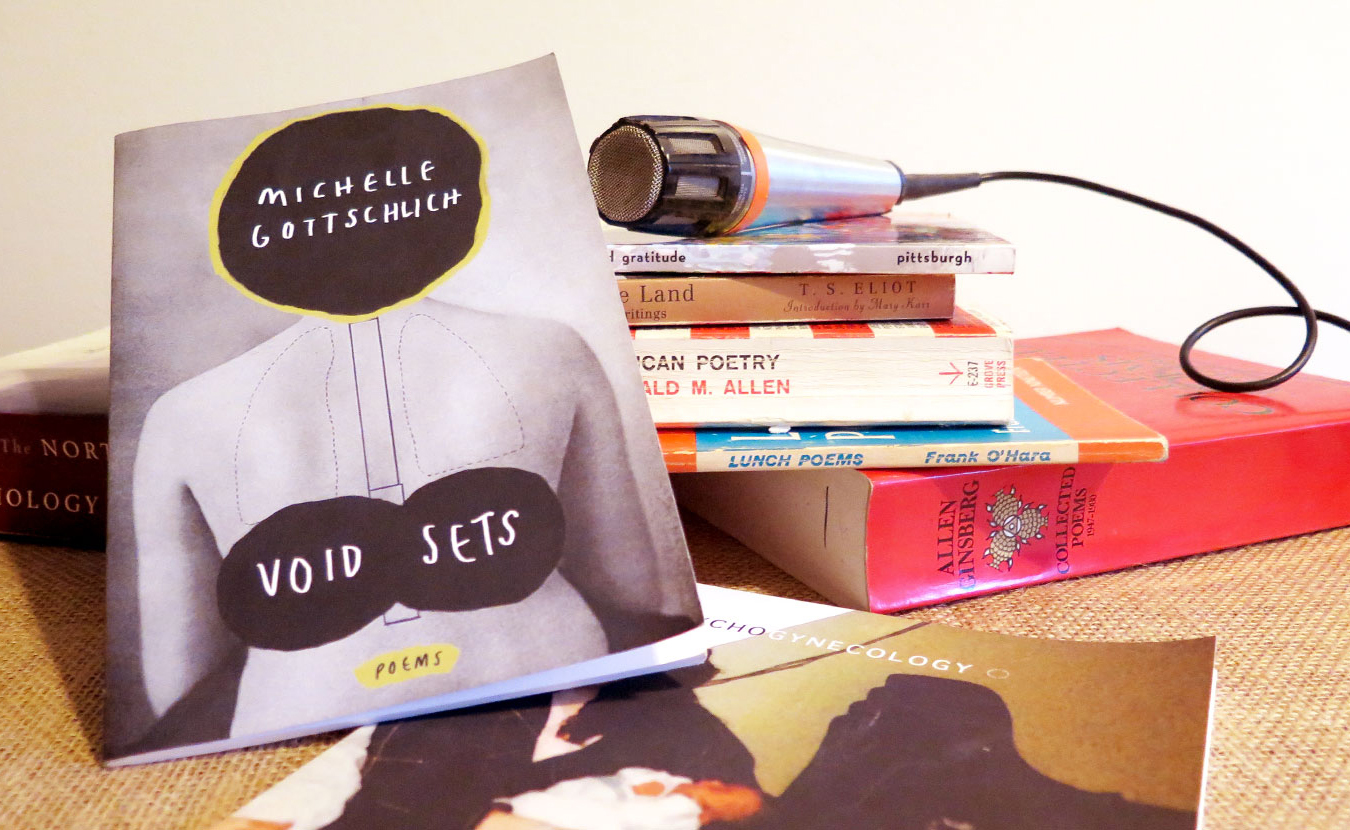

Spoken word and slam poetry challenge our expectation that poems should require time to study and unpack. This is as much a challenge to traditional form as it is to class divisions and body politics, because if poetry requires an “academic approach,” then it is an art form primarily produced for an educated class. Of course, many important and highly anthologized poets like Gwendolyn Brooks and Frank O’Hara have done this same work on the page; the live element of stage drives home the idea that poetry can reside as impressively in a body as in a college reading list.

Stage poetry also shares roots with the African American oral tradition and Southern Baptist ministers. The work is meant to be delivered to an audience and invites their synergistic responses. Genres of stage poetry often employ the rhetorical principle of signifying, which is the defining characteristic of African American spoken word, rap, and performance art, and includes various practices like call-and-response and improvisation, according to Adam Bradley and Andrew DuBois in The Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press, 2010). This is to say, there is a long history of poetry as an oral art form that grew completely contrary to the traditional Western canon. It’s not just that the page (or literacy, or access to education) is rejected as necessary to a poem; stage poetry is a radical tool for building community and speaking to a collective grief.

Poetry is still most often considered a high or fringe art. I’ve noticed that people tend to feel that only those who study poetry can adequately consume it. Page poetry can be any level of difficulty, but I understand this reputation. Shakespeare is difficult, the modernists are difficult. But in defense of difficult poetry, T.S. Eliot famously said, “Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood,” by which I think he meant that a successful poem should be stunning from the first read, even if you don’t understand it yet. It stimulates and unlaces our perceptions of, among other things, perception itself. As you unpack the meanings from the content, the aesthetic experience of each word refreshes and becomes newly stunning again. It takes time. I’ve also noticed it requires a greater level of vulnerability than learned confidence.

A poetry reading during a Ledge Mule Press record release party at I Fell in September 2015. | Limestone Post

Complex page poetry has also been widely written to combat (and enforce) systems of oppression. Contemporary poets like Harryette Mullen, as well as poets of the Harlem Renaissance and the Language poets, play with all facets of words and phrases — common uses, pronunciations, connotations, spellings — to defamiliarize and reveal the inner politics of ordinary speech and poetic convention. With the page, the possibilities for form and play are infinite. It can bear the weight of deeply layered language, like a dream in which the latent content can be reached only after you’ve re-examined the surface content. Then it is both — equally and at once — the sheer imagery and the buried, unsayable thing. The goal perhaps is not to communicate urgently but rather to express more completely than what our common language usually allows. Of course, there’s also the deep and simple pleasure of reading something that moves you, which elements of live performance can’t quite touch.

A tense gap

So how does the page vs. stage gap manifest in Bloomington? In many ways, the gap is small, but so is demographic variety. The price of undergraduate tuition and access to higher education create a profound boundary. The IU English Department fully funds its MFA students, but their original access to and success in academia remain a hardy prerequisite. Given that most writers living in the Bloomington area have attended or moved here for college, events often provide a mixed bag within that group. Readings typically feature current or former students, professors, and DIY (or otherwise unaffiliated) poets in more or less equal share. However, poets and slam poets read together less commonly. The slam community is perhaps more insular given the particular form of a poetry slam. But this isn’t definitive. For example, Hollett doesn’t typically perform at slams, but instead reads poems in the slam style at universities, community events, and special gatherings like The Back Door’s benefit for the victims of the Orlando shooting. Page and stage communities are most noticeably divided by venue. Page poets read most often at MFA student readings, coffeeshops, house shows, some bars, or not at all. Stage poets read most often at poetry slams (Rachel’s Cafe when it was open, The Bishop Bar, auditoriums at IU), open mics, and assorted public events.

Considering the aims of poetry — what kind of work it should do — things get a little blurry. Many poets independently publish and perform their work from a punk and DIY perspective, representing endeavors of antiestablishment, antiacademic creative work. While slam is originally rooted in antiacademic politics, IU is one of many large universities that now boast a nationally competing slam team, which seems to erase a lot by way of appropriation but also opens up opportunities and possibilities for what can be considered “academic” work.

Students Alan Czerwinski (left) and Harlan Kelly (second from right) discuss the craft of writing with poets Ross Gay (second from left) and Gabrielle Calvocoressi (right) in a workshop taught by Indiana University Associate Professor Adrian Matejka (center). | Photo by Zijazo Smith

“That performance poetry is more egalitarian, IMO, is the most important distinction,” writes Matejka. “I started writing poetry after failing as a rapper, but I was in undergraduate poetry workshops studying rhyme and meter. I was prepping for the page, but I was also in a band so I was performing on the stage with music. About that same time (1993), I learned about poetry slams but never participated. I wasn’t (and still am not) good at it. But I attended them all of the time and admired the work the performers were doing. So from the lid, I was between these two expectations of poetry and wasn’t really any good at either of them.”

Matejka recently read in the Page Meets Stage series at the Bowery Poetry Club in New York City, which intentionally pairs “academic” poets with spoken word poets, drawing out and blurring these distinctions. IU regularly invites famous poets and slam poets to read and lecture on campus, though rarely — if ever — are they paired in readings. Poetry slams bring out large crowds of students, which is unsurprising considering the elements of live entertainment built into slam. Even when relatively famous poets like Seamus Heaney, Gerald Stern, or Nikki Giovanni visit (as they did when I was a student), there is the special sense — which feels distinct from a filled poetry slam — of seeing an extremely rare bird. It’s immensely important if you’re part of that odd group of people who happen to know a little about ornithology.

If there’s a tense gap between page and stage poetry here, I’m not sure yet how to widely source it, but I can admit that I’ve felt it and have been a part of it. There’s the traditional mode — going to college, doing an MFA, publishing with the big journals, publishing a book — that lines a pathway by which talented voices can make a living and readers can find their important works. While often financially exclusionary and still preferential of certain bodies, access continues to expand and include more diverse poets, due much in part to the public popularity of spoken word and slam poets. Alternatively, slam competitions also provide a source of financial support through prizes to competitors, which, until the recent indoctrination of slam into universities, skirted many of the academic, racial, class, etc., biases of the traditional approach. Yet as a page poet, this has caused me some anxiety. If poetry is not pursued through the normal, albeit exclusionary, institutions, then it is pursued through capitalism. I’ve worried that the immense popularity and standardization of slam form is signaling the commodification of poetry and the end of poetry as an ambitious and amorphous fringe art.

The first Bloomington poetry slam I went to, I was shocked by the full room. Listening, I felt angry and betrayed, sold out for a three-minute song. I resented how easy it seemed, how rhythmically formatted and oiled for claps. I was jealous of the crowd and wanted something else. I wanted to put poetry back on the fringe, to protect it from becoming something anyone could love and use so easily, while my identity was wrapped up in something that had felt special and weird. But it’s not just slam and performative poetry. Twitter, Tumblr, and Instagram have totally changed the consumption of poetry and art. While they make up a far more egalitarian platform than any others proceeding them, the consumability of the writer’s performed internet persona brings up a unique set of challenges. They must openly craft and sell a brand, which is compensated in some way I don’t quite understand by views and internet traffic. The notion of page as a blank space becomes far more complicated. I suspect my fears may sit near the heart of whatever tension is currently between stage and page, compared to Edmundson’s dated argument. Cool, trendy, authentic are all ideas that contemporary artists are quite concerned with. With regards to my fears over slam, I revealed those to Hollett and took comfort in what she said:

“It is entirely possible that slam will be co-opted by the very forces it attempts to critique, if it hasn’t been already. I mean, slam is not, and has never been, infallible or accessible to everyone and to romanticize it now would be historically dishonest. I do have confidence that no matter what happens, radical, exciting voices will emerge along its edges and these voices will either reclaim slam or create something new from the ether. Either way, the elements I have interacted with most in my experience of slam — subversion, personal and political power, liberation, self-expression, and courage — will likely compose whatever its next iteration becomes. There are still so many injustices to resist and revolutions to plot, after all.”

And in regard to my fears over page poetry, I take comfort in Matejka’s response: “I believe that poetry is for everyone. In the end, it’s all about communication and pushing back against some amorphous thing — emotional, social, political, etc. What matters most is the work the poem does, not the mode.”

And besides, what could I suggest anyway? That we should stay stuffy and quiet and poor so that our work doesn’t risk getting fully eaten up by the capitalist machine like every other art form? Probably not. Even if some of poetry became pop music or a Michael Bay film, I think things would still be fine. The page vs. stage topic is an interesting one in the end, because really, it’s utterly arbitrary. These are made-up terms people say in class when they don’t have the right words to get at what they’re feeling. Snug between them are the questions, Why don’t I like this? Why do I want the things that I want? Why am I holding someone else back? Who reads Harper’s Magazine still, anyway?

No Replies to "Page vs. Stage: The ‘Deep Rift’ in Poetry Today"