As we decide what constitutes a good life — and try to ensure that everyone has one — we often become embroiled in pressing fights with individuals and institutions that oppose our efforts. In our current sociopolitical climate, we are also witness to the frequent conflicts that occur among people and groups with whom we supposedly share similar overarching values and ideologies. For example, tensions between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton supporters during and after the presidential primaries in 2016, or recurring clashes between Black Lives Matter protesters and White liberals, demonstrate the deep rifts in policy and beliefs that can occur among people who otherwise identify as leftists of some kind.

These disagreements align with claims that the left is wont to “eat itself” and are accompanied by pearl-clutching exhortations for us to stop in-fighting, dammit, and unite against the “real” enemy. But how do we unite when far too often the “real” enemy is arbitrarily limited to our morally bankrupt federal administration, as if cities under Democratic leadership and communities with a progressive citizenry cannot also be home to injustice?

Hollett explains that there can be “deep rifts in policy and beliefs that can occur among people who otherwise identify as leftists of some kind.” Pictured here in January 2017, local activists and residents came together during the Inaugurate the Revolution event in protest of Trump’s election. | Photo by Mike Karlin

Conversations about questionable activist initiatives and oppressive government policies are not just playing out on the national stage but are also situated firmly here at home. Take, for example, a rally in Bloomington this summer to protest the policy of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to detain immigrant families and separate children from their parents at the border. While most leftists knew and agreed that the policy was cruel and should be opposed, there was some notable controversy over the decision to do so in the form of a rally on the Courthouse lawn, not only because the location was disassociated from ICE offices, police stations, and jails where people are actually held, but because the rally seemed unaccompanied by any identifiable objectives.

Prior to the rally, a handful of individuals questioned how meeting at the Courthouse to chant and listen to speakers for a few hours would help keep vulnerable families safe. These concerns led to a series of somewhat heated (and public) Facebook exchanges between rally coordinators and those who were advocating for an action that offered a more explicit challenge to ICE. (Another group met at the Zietlow Justice Center a month later.)

I spoke with “Mary Holly” (not her real name), a local sex worker and queer antifascist, about these exchanges, and she responded by asking, “What was the goal of that rally? Did we just do it because we didn’t know what to do and felt like we needed to react somehow?” Holly had advocated for turning the rally into something more akin to direct action and expressed frustration that the majority of the rally planners and attendees seemed loathe to consider doing so. Holly says, “Clearly, a rally looks cuter on Instagram than taking a street medic training, sitting at home running jail support with a pile of people’s emergency contacts, or watching people’s kids — all things you can do to support direct action without putting yourself in the direct line of fire. People rarely want to hear that though, because the goal most of the time seems to be about making ourselves feel better, not putting pressure on an institution to make any kind of change.”

Holly’s grievances help illuminate the difference between organizing campaigns on the one hand and symbolic activism on the other, where the latter, which is common in many communities, including ours, is often unrelated to efforts to build power and win in the long term. John Lacny, a labor union staffer and former Bloomington resident, says that people on the left need to “make a conscious decision that we are going to wage real campaigns with a credible plan to win actual victories that people understand, not just [perform] acts of moral witness where we ‘speak truth to power,’ whatever that means.”

Joe Varga, left, during a Black Lives Matter disruption on College Avenue in 2014. He says, “A motorist shut off his vehicle and joined our blockade, and gave me this fist bump.” | Courtesy photo

Many of the rallies we hold in Bloomington do seem more invested in demonstrating righteous indignation than being linked to robust, multifaceted organizing initiatives. And while it is certainly plausible that immigrant families living in the area may have benefitted emotionally by seeing a visible display of support from those around them, the urgent questions, such as what we would collectively do if our neighbors were detained tomorrow, or what we’re going to do to stop the detainment of people at the border today, cannot be answered or acted upon without some complementary (or perhaps completely different) approach. Joe Varga, an associate professor of labor studies at Indiana University who has been active in many causes over the years, says, “Good people have no trouble today expressing outrage, but they seem stuck at translating it into action.”

This may be because organizing, as opposed to previously described activisms, is a hard-earned skill. Organizing emphasizes long-term strategy and tangible wins over disconnected, short-lived protests. As a result of this longitudinal focus, organizing requires that we begin our campaigns by building a base powerful enough to take on dominant groups, with all of their attendant systemic, political, and financial advantages. “We need to get beyond the mentality of always mobilizing the same ‘stage army of the good’ to go to the same tired rallies,” Lacny says. “That’s what ‘activism’ typically amounts to. [Organizing] means taking responsibility for the fact that we have to bring a whole lot more people into movements for progressive change if we are interested in actually winning, rather than just feeling good about ourselves.”

Indiana University graduate students protest the federal proposal to tax their tuition remission as income in spring 2017. | Photo by Alexandria Hollett

Of course, this is easier said than done, partly because “bringing a whole lot more people into movements for progressive change” necessitates that we ally ourselves with people who may or may not share our exact interests, backgrounds, levels of experience and expertise, and theories of justice. To work with people in this way requires a massive commitment to the gritty, deeply human and humane task of interacting with real people with real flaws in real time. In order to do so productively and honestly, we may need to consider relevant disagreement and critique as an opportunity for productive dialogue as opposed to a distraction from fighting the aforementioned “real enemy.” As Holly says, “We don’t actually all agree on who the ‘real’ enemy is. A huge chunk of the left seems to think it’s Trump and his administration, but Mike Brown was murdered by police long before Trump. The whole country was founded on genocide and slavery and this violence is written into our laws and culture, no matter who is president.”

When it comes to who or what we should be fighting, Varga is matter-of-fact. “The only real enemy is injustice,” he says, “and injustice can [also] manifest in allies. … And to do nothing when supposed allies are in the wrong is morally irresponsible. The fight over the publication of addresses of victims of overdose is a great example [of this].”

Hollett says there is a “difference between organizing campaigns on the one hand and symbolic activism on the other, where the latter, which is common in many communities, including ours, is often unrelated to efforts to build power and win in the long term.” | Photo by Alexandria Hollett

Varga is referring to a recent clash between activists and the mayor’s office over the publication of the names, ages, addresses, and causes of death of victims of drug overdose on Bloomington Revealed, a website run by the City of Bloomington. Mayor John Hamilton stated that the compilation and release of this sensitive information was part of an initiative to increase government transparency and paint a more accurate picture of drug addiction. However, individuals who lived at these addresses and other concerned Bloomington residents asserted that the release of the data violated their privacy, traumatized hurting families, and increased stigma.

Over the course of a week and a half, these concerned individuals engaged in an intensive phone, email, and in-person campaign to get the data taken down. The city initially responded by keeping the information public but making it more difficult to find on the website. When the mayor repeatedly refused to take the information down completely, however, harm-reduction organizers, some of whom were personally affected by the publication of the data, planned an event at the mayor’s residence. Within a day of the announcement that there would be an action at the mayor’s house, the information was taken off the city’s website and the action was canceled.

Before learning the full scope of the campaign to get the sensitive information deleted from the city website, I had asked a few organizers how we push mainstream Democrats to adopt more justice-oriented policies. Lacny said, “Not by debating with them and thinking we’re going to rationally win over their hearts, but by actually exercising power so that they have to respond.” After first appealing to the moral reasoning of city officials — to no avail — organizers and community members exercised their power by planning a demonstration with more teeth. It is worth noting that as soon as the mayor’s home and family were put uncomfortably in the public eye, the activists’ demands were met with alacrity. Their plan worked without them even having to go through with it.

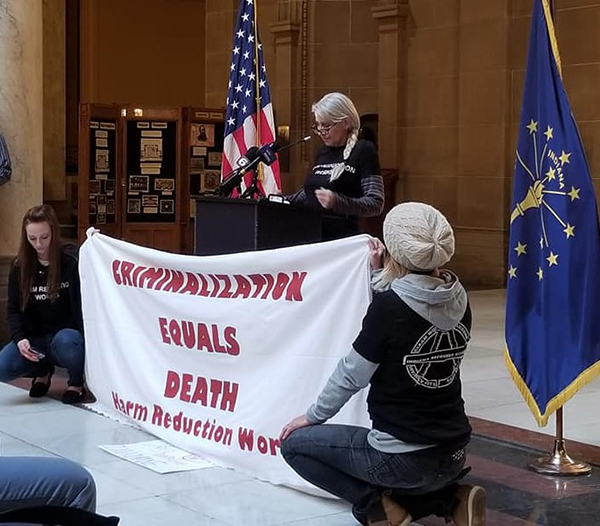

Christy Thrasher speaks at the Indiana Statehouse during a protest of the signing of House Bill 1359 — “a drug induced homocide law” that, Thrasher says, “would allow prosecution of the person supplying the drugs that led to an overdose death…. The claim was that it would reduce overdose deaths while all evidence suggests otherwise, that it will actually increase deaths and fear of dialing 911 in an emergency.” | Courtesy photo

From an organizing standpoint, then, this was a significant win for families and allies. However, their victory was almost immediately overshadowed by a large number of otherwise progressive individuals who began to view the (canceled) action as a vicious attack on the mayor and his family by a troupe of bullies and thugs. These individuals asserted that the mayor and his family were victims of privacy violations, employing the very same logic that activists used to explain why addresses and other sensitive information should not have been released to the public: That homes are sacred, that people should feel secure and safe within them, that everyone has a right to privacy, that everyone deserves respect. The action planned by organizers and activists was a deliberate attempt to drive these points home — literally. It was also a matter of real urgency: The longer the information remained available to the public, the more risk to families, including minors, whose pain was being treated as little more than a data point.

Christy Thrasher, one of the organizers of the action and the C.A.R.E.S. Harm Reduction Clinic Coordinator for Jackson County, says most of the concern that was generated for the mayor seemed to come from individuals who had very little knowledge of the steps that activists initially took to get the information deleted from the website, including going through the “right” channels of contacting their representatives, requesting meetings, and showing up at City Hall. “I wouldn’t advocate that every time we have an issue with the mayor, we show up at his house,” Thrasher says, “but this was directly connected — the tactic was relevant [to the issue].”

One particularly irate individual implied that Thrasher and others were fascists. When I asked Thrasher what kind of fascisty things they were going to do during the action, she laughed gently, saying, “We were going to show up with flowers and have 54 people symbolically die. We were just trying to say, ‘Please honor our dead.’” She went on to say, “The event would have never been planned or announced had people felt heard and respected. This was completely avoidable on the city’s part. That information needed to come down yesterday. It shouldn’t have been published to begin with.”

Activists symbolically die at a protest at the Statehouse. Thrasher and other local activists organized a similar action at the mayor’s house, but was cancelled once the City removed sensitive information about local drug overdose deaths from their website. | Courtesy photo

Thrasher’s experience of being perceived as uncompromising and aggressive is certainly not a new phenomenon for those who push against existing power structures, regardless of political affiliation. Historically, a number of the left’s greatest heroes, from Martin Luther King Jr. to Eugene Debs to Lucy Parsons, employed seemingly radical tactics that shocked and dismayed many of their contemporaries, including those who claimed to have an alignment of values. In our conversation, Thrasher spoke of the exhaustion and pain she experienced trying to push the mayor and his team toward a more humane position. “There’s no acknowledgment that these events were stressful for any of us [the organizers and other families] or that this was incredibly uncomfortable,” she says. “I don’t know how much longer I could have kept doing it.”

Sustained activism is a huge obstacle for any campaign, particularly when most of us are not being compensated for our work as organizers. And although there is much joy to be had in forming coalitions, building power, and promoting human flourishing, these same activities can come at a cost to our emotional, mental, and physical well-being. However, if we are serious about doing more than performing some semblance of feel-good, but basically toothless, justice work, we are going to have to embrace these challenges.

To that end, Lacny has some advice for those of us who would like to do so more strategically. “Before starting any kind of action,” he says, “we need to have a clear understanding of the objective we’re trying to achieve, and that should fit into our larger strategy for shifting power from the oppressors and exploiters into the hands of the oppressed and exploited. It is only when real fights produce actual victories that people learn that they do have power, because we demonstrate that it is possible to change things through collective action.”

Hollett says, “Bloomington is rife with evidence that recent economic decisions may be harmful to any number of people.” This includes resistance to harm-reduction initiatives in the wake of the opioid epidemic. Pictured here are folks attending the 4th Annual Overdose Remembrance and Candlelight Vigil in late August. | Limestone Post

Lacny’s advice is timely for all of us, especially in light of ongoing tensions between concerned constituents and the city — tensions that gained traction when the launch of the Safety, Civility, and Justice Initiative in 2016 coincided with an aggressive anti-panhandling campaign downtown. Although the campaign had its supporters, expelling individuals experiencing homelessness from People’s Park and Kirkwood Avenue did nothing to address the root causes of poverty, regardless of the city’s other efforts, and instead contributed to the further vilification and excommunication of people who already live under constant threat and duress. Distrust escalated further when the mayor gave the green light to purchase a Lenco BearCat, a non-military grade armored vehicle that has been used by law enforcement agencies around the country to halt protests and intimidate protesters, particularly in communities of color that are fighting police violence. And still more agitation was produced when the city announced a moratorium on new addiction-treatment centers, which was quickly recanted due to widespread criticism.

In light of these examples, we should be vigilant against bad policies and misguided actions, including when Democrats hold positions of public office. Recent events within the Monroe County School System, from racist curricula being disseminated to elementary school students to allegations of racism influencing the suspension and eventual termination of one of the district’s only Black teachers, suggest that we have more work to do when it comes to living up to our presumed commitment to equality.

In terms of anti-classist organizing, Bloomington is rife with evidence that recent economic decisions may be harmful to any number of people, of which the sanitation of the downtown area, the ever-increasing sprawl of Indiana University and off-campus student residences, the erection of million-dollar condominiums, and the lack of affordable housing are just a few examples. When it comes to public health, the ongoing opioid epidemic and continued resistance to proven harm-reduction initiatives such as needle exchanges suggest that this is also an area of continued concern.

Hollett performs “Blessed Are The Persecuted: An Open Letter To The Indiana Legislature” at a protest of the passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 2015. | Courtesy photo

The good news is that Bloomington is full of people who care about issues of justice, and that includes individuals who have come under scrutiny in this article. At the risk of sounding suddenly Pollyana-ish, it would likely behoove many of us to engage more charitably with each other as we try to make sense of the complicated, messy, joyful, exhilarating work of building the world we all deserve.

Although this is a daunting task (and much more complex than I am making it here), radical leftists should try to involve ourselves in initiatives that engage the broader Bloomington community beyond our pocketed collectives, as opposed to offering criticisms from the sidelines a few days before an action is set to take place. By that same token, however, those who participate in activism, policy-making, and organizing also need to stop assuming that good intentions or progressive values automatically shield us from critique and vigorous protest when we err. To be on the left is not inherently synonymous with enacting equity, and any policy that furthers cultural imperialisms, supremacies of whiteness, or the marginalization of vulnerable communities should be resisted early and often. While our goal should be to create strong alliances across a variety of interests, we cannot build power if we don’t first contend with our sometimes radically different visions of what a liberated future looks like, and for whom.

Bloomington is a microcosm of broader conversations — some of them national, some of them global — where systemic issues are localized and the consequences of public policies and injustices manifest directly in one’s neighborhood, school, workplace, and government. It is also a place where the people we protest on Saturday may be shopping next to us at the grocery store on Sunday.

When we consider activism in this context, Varga notes, “you can’t get people to rethink the structures that have guided their lives by screaming at them, dismissing them, or treating them with contempt. Radical solidarity involves meeting people where they are, not where we would like them to be.” Holly says that this is frustrating work when there is a disconnect between the people who “know this is a marathon and are fighting for total liberation and folks who think Trump is the only issue and would be happy to go home and drop the fight if he were impeached tomorrow.” In light of this, Varga would like to see “more emphasis on solidarity from all factions across the left-liberal spectrum.” Holly states, “We need to be more committed to each other and our collective liberation than anything else.” Thrasher says, “We are supposed to challenge things that are clearly wrong. We have a responsibility to each other to do that.” Varga adds, “Nothing is going to save us but us, if we are worth saving.”