In 2004, Dr. William Cooke arrived at the southern Indiana town of Austin as a newly minted doctor with a desire to serve what he knew was an economically and medically underserved community. Not only did Cooke, author of Canary in the Coal Mine (with Laura Ungar), find, on arrival, that Austin was one of the epicenters of the opioid epidemic, but he later endured not just one epidemic but two, along with a pandemic. Had he known the extent of pain and suffering awaiting him, he says, he might’ve turned around and left town.

Dr. William Cooke wrote the book ‘Canary in the Coal Mine’ (with Laura Ungar) about his experiences during the opioid epidemic in Austin, Indiana, a place that also had the ‘worst drug-fueled HIV epidemic in the United States.’ | Courtesy photo

Cooke’s experience mirrors what was happening around the United States before and after he arrived in Austin. Since 1995, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration easily approved OxyContin, a timed-release painkiller introduced by Purdue Pharma, the opioid epidemic has raged on in small rural towns and in the suburbs, with the majority of those overdosing in the age range of 18-60 years old. Now the story, spanning more than two decades, can be summarized in three waves and maybe a fourth.

The first wave, overprescribing prescription opioids, arose from the approval of OxyContin in 1995. Led by Purdue Pharma’s aggressive marketing campaign, this approval coincided with a Joint Commission on Accreditation for Healthcare Organization’s recommendation. It created new pain management standards tying healthcare quality and patient satisfaction to pain control, designating pain as the “5th vital sign.”

This emphasis on pain management propelled increased prescribing practices of OxyContin by primary care providers. “We [doctors] were told that there was evidence to support the use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain, that they were better than the alternative, and that we would be remiss in our duties not to prescribe them,” says Dr. Anna Lembke, author of Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It’s So Hard to Stop. Doctors were told, Lembke says, that “as long as we were prescribing for a bona fide condition, the chance of addiction was very, very low.”

According to Lembke, chief of addiction medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine, the campaign was an aggressive strategy by opioid pharmaceutical companies. Using academic physicians, regulatory agencies, and professional medical societies that parroted unproven scientific claims, it was “marketing disguised as science,” as Lembke coined it.

Deceived, physicians prescribed opioids for bad backs, dental pain, or other non-terminal conditions. Patients, too, became accomplices by doctor-shopping for pills, selling them, and crushing and snorting OxyContin, thus making it more deadly.

Dr. Anna Lembke, author of ‘Drug Dealer, MD,’ says doctors were told for years that opioids could be used safely to treat chronic pain and ‘the chance of addiction was very, very low.’ | Photo by Norbert von der Groeben/Johns Hopkins University Press

Once states began cracking down on pain clinics and pill mills while also implementing prescription-monitoring services to prevent users from doctor shopping, the second wave, beginning in 2010, marked the rise in deaths from heroin. When the FDA required Purdue Pharma to reform OxyContin so it could no longer be snorted or crushed, users moved on to more illegal drugs. These actions invited Mexican drug cartels, more specifically from Nayarit, Mexico, which typically stayed away from larger cities to market black tar heroin in smaller, less populated cities and towns in Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, and other states.

Starting in 2013, the third wave marked a rise in illicit synthetic opioids when dealers cut heroin with fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. All the while, physicians continued to prescribe opioids despite the restrictions put in place. According to Lembke, prescribers wrote “enough opioid painkiller prescriptions in 2012 to medicate every American adult around the clock for a month.”

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared a prescription drug epidemic, citing physicians’ overzealous prescribing of opioid painkillers and psychotherapeutic drugs as a contributing factor. The bulletin laid out a 12-step prescription guideline for providers, urging them to limit prescription dosages and prescriptions of opioids for first-line chronic pain treatment. First-line chronic pain treatments often include ibuprofen, acetaminophen, physical therapy, or other types of relief. Physicians were encouraged to try other options prior to prescribing opioids.

Once the CDC recommendation came out, a collective sigh of relief rippled among Lembke’s colleagues. “Physicians were waiting for an authority figure to give them permission not to prescribe because, for so many years, there was so much pressure to prescribe even against our better judgment,” says Lembke. It was as if physicians were saying, “Thank goodness we now have permission to say ‘no,’” she says.

Collision course

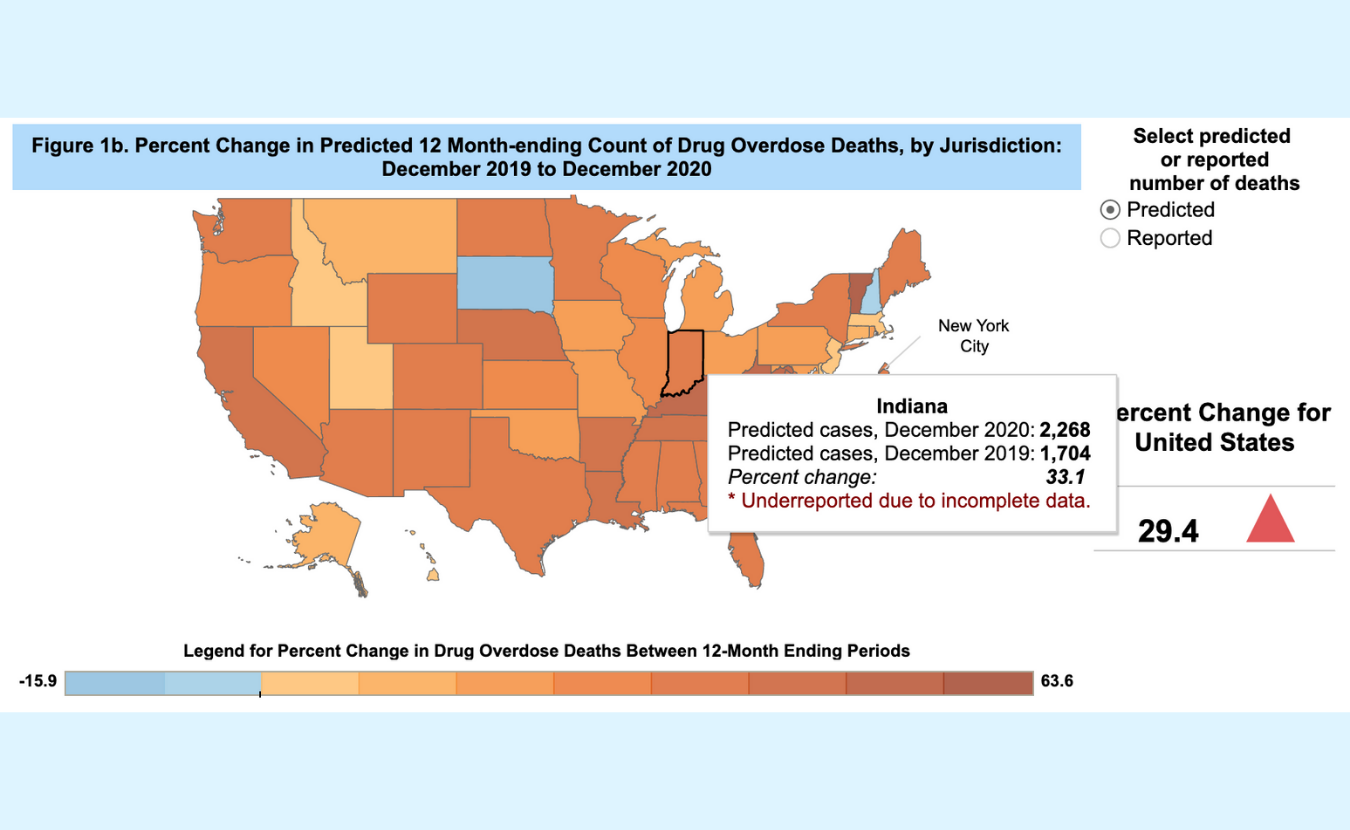

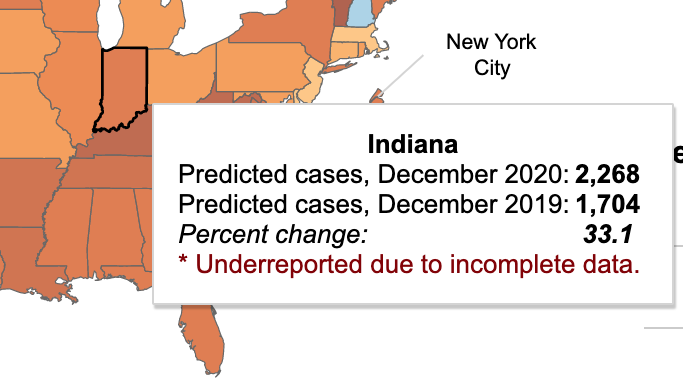

Even with these changes, the opioid epidemic rages on. To date, more than 841,000 people have died since 1999 from drug overdoses due to prescription and illicit opioid use, with an estimated 10 million people still using opioids. Now, couple the opioid epidemic with the COVID-19 pandemic and this collision could be coined “the fourth wave.” Recently, the CDC released provisional data for 2020 showing 93,331 drug overdose deaths in the U.S., a jump of nearly 30 percent from 2019. Indiana reported 2,268 drug overdose deaths in 2020, a 33 percent increase over 2019.

A detailed inset from the CDC map above shows Indiana reported 2,268 drug overdose deaths in 2020, a 33 percent increase over 2019.

The most significant impact was the lack of accessibility and availability of services as the pandemic hit. But quick-footed addiction specialists and healthcare providers adapted. “A lot of places went virtual, but we had a lot of people who did not have access to virtual meetings,” says Melissa Stone, social worker at the Bloomington Police Department. “We also had people who didn’t want to do it virtually.” But everyone, including those with substance use disorder (SUD), had to adapt.

Some organizations kept their doors open, with strict precautions to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The Indiana Center for Recovery opened its detox facility in March 2020 and, the same weekend Indiana shut down, they took their first patient. “We were full in a week,” says Jackie Daniels, the center’s vice president of communications. “Frankly, it was the worst time for us to close our doors to the vulnerable populations that we treat,” she says. “Patients needed a place to go.”

With the pandemic came social isolation and increased financial stresses contributing to the increase in overdoses. For some people with SUD, their addiction and mental health worsened because of these stressors, says Brian Peek, certified peer recovery coach at Daviess Community Hospital and Daviess County Community Corrections. Others, he says, “were afraid to go to the hospital because they didn’t want to get COVID-19.”

Melissa Stone, a social worker at the Bloomington Police Department, says a lot of people needing healthcare services during the pandemic could not access virtual sessions, while others did not want to attend virtually. | Courtesy photo

Still, others found the courage to seek treatment, says Phil Stucky, executive director of Scott County THRIVE, which is based in Scottsburg, Indiana, just a few miles south of Austin. The organization found that 1,883 people reached out for assistance within the pandemic year in the nine counties they serve. But overall, says Susan Harrington, program manager for the Stride Center in Bloomington, “I would say that due to COVID and opioids, we have seen an increase in use amongst the populations that we serve.”

For healthcare workers and addiction specialists, the pandemic provided additional pressure amid an opioid epidemic. Prolonged exposure to stress can result in burnout or even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Healthcare workers can experience difficulty concentrating or paralyzed functioning as a result of this stress. One study found evidence related to the COVID-19 pandemic and previous epidemics that facing these concurrent issues had a cumulative psychological impact on how healthcare workers responded to outbreaks. Of those healthcare workers, 73 percent experienced PTSD during outbreaks, with 10 to 40 percent experiencing it one to five years later.

Those who worked in addictions services but were also in long-term recovery themselves had to be protective of their health so that stress did not overcome their recovery efforts. “You have to know what your boundaries are,” says Peek, “not just working with folks but in going into certain environments to help people.”

Stucky agrees that it was hard on his staff, the majority of whom are also in long-term recovery. “Change for people in recovery is difficult,” says Stucky. “This pandemic changed everything. It was very, very hard.”

Cooke himself experienced two epidemics and one pandemic. He saw countless patients die of overdoses and he treated hundreds of patients, many of them young, for HIV. During that time, his marriage also failed. In his book, he details how he got to the point:

“Looking over the ruins of my life, I decided that I couldn’t continue to work in Austin. Although I had no idea what to do next, I knew that I was done trying so hard. Seeking solitude and space, I ran as far away from Austin as I could.”

Though he returned to Austin less than a year later, even today, Cooke says, “I still struggle at times and have some PTSD from experiencing the trauma vicariously and personally.”

Dr. Amnah Anwar, program director of the Indiana Rural Opioid Consortium, has talked to providers in rural Indiana but was often told ‘opioids are not a problem in our community.’ | Courtesy photo

Some progress is evident. Local communities gutted by the epidemic, like Austin, have found solutions that will help them address these crises, though sometimes progress is hampered by stigma and denial. Indiana Rural Opioid Consortium’s program director, Dr. Amnah Anwar, has traveled rural Indiana areas working on prevention.

The Indiana Rural Opioid Consortium (InROC) started as a pilot program in 2017. Anwar is a physician and general surgeon from Pakistan, though she does not practice here in Indiana. When she began talking to providers, she found that most of them were in denial as to the existence of the opioid epidemic. She was told, “InROC is at the wrong place because opioids are not a problem in our community.”

She confronted biases that people with SUD were not sick but morally weak. “This stigma prevented people from accessing treatment and talking about this disease as a disease,” says Anwar. It also barred treatment options like medication-assisted treatment, such as buprenorphine, methadone, and other drugs that reduce the impact of addiction.

“Having a clinical background and having a physician/surgeon mind frame,” says Anwar, “has helped me to know that when we are talking about these substances like opioids as an epidemic, what we are not thinking of it as is a chronic disease.” The substances may change, whether they are opioids, meth, cocaine, or psychostimulants, she says, but providers have to look at it as a chronic disease and address those risk factors that come with it. “Only then will we be able to grapple with the situation. Otherwise, it will jump from one substance to another.”

It takes a recovery community

Once you address substance abuse as a chronic disease, the question becomes how you treat it and what services you need to provide to treat it. A research brief by the IUPUI Center for Health Policy shows that medication-assisted treatments can be highly effective in treating addiction, but handling a whole epidemic without a cohesive approach is not a solution.

Phil Stucky, executive director of Scott County THRIVE, based in Scottsburg, Indiana, says the pandemic created additional pressure on people providing addiction services amid an opioid epidemic: ‘This pandemic changed everything. It was very, very hard.’ | Courtesy photo

Recovery experts believe that treatment and recovery need a communal approach to address the root issues like housing, transportation, and access to care. To do this, many communities hit by the opioid epidemic have reinvented themselves as recovery communities, increasing the options for treatment and prevention and making the most of the services they have.

As Cooke writes in Canary in the Coal Mine, in early 2015 he didn’t know how bad the HIV problem was in Austin until he read about it in the local newspaper. There was no public warning or involvement. By Valentine’s Day 2015, the Indiana State Department of Health had confirmed 26 HIV cases and 4 preliminary positive cases since December 2014 in his town of 4,200 people, which was crowned the “worst drug-fueled HIV epidemic in the United States.” By June 2019, the number of HIV cases rose to 235 people. The question became how a small community manages not only an opioid epidemic but now an HIV epidemic as well.

Cooke strongly believed the community needed to come together to cultivate healthcare opportunities necessary to treat these twin epidemics. And so they did. They started by collaborating with state and national organizations. Then with local organizations. Eventually, out of those long-term efforts came Scott County THRIVE, a recovery community organization.

A recovery community like THRIVE is an organization that serves as a resource hub for community organizations to mobilize addiction recovery services. Scott County THRIVE started in 2018. It oversees efforts in 21 counties and has two satellite hubs in Fayette and Decatur counties.

Brian Peek, certified peer recovery coach in Daviess County, says that for some people with substance use disorder, their addiction and mental health worsened because of social isolation and increased financial stresses from the pandemic. | Courtesy photo

“We advocate and educate the community with recovery systems of care with substance use disorder and also mental health,” says Stucky. “One of our goals is to educate the community — from employees to employers to community stakeholders — what a recovery community looks like in Scott County.” For Stucky, the links between mental health and physical health are critical. “It’s all the same conversation, and it should be looked at holistically,” he says.

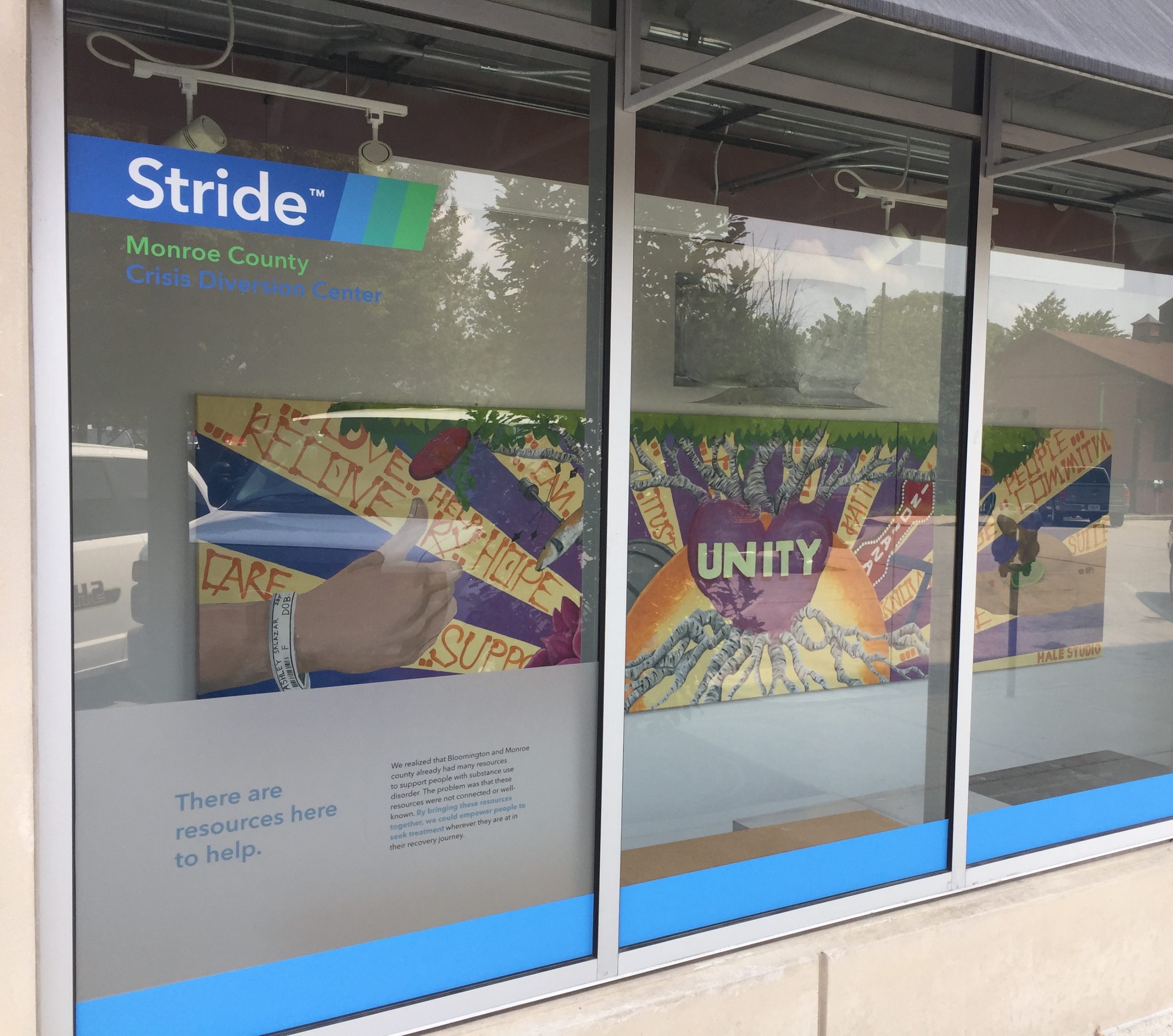

The same is true in Bloomington with the newly christened Stride Center at 312 N. Morton St. Formed by 37 local agencies and partners, their mission was to treat addiction as a public health concern and fill what they saw as an after-hours service gap for addiction services in Bloomington.

Initially opening its doors in August 2020, the center is not only serving folks on a referral basis but has also opened its doors to those who walk in requesting services. “Stride is a voluntary diversion center,” says Harrington. “We are a resource hub.” They work closely with local and county law enforcement, the hospital, local mental health and addiction agencies, local shelters, and other recovery services.

Peer recovery coaching

Ninety-five percent of THRIVE’s employees, including Stucky, are in long-term recovery themselves, so peer recovery is an important facet of THRIVE’s impact. With peer recovery, a certified peer recovery coach gets a chance to relate one-to-one with a person with SUD, sharing experiences. “There is something to be said about that shot of hope that’s given as soon as someone says, ‘I have been where you are at, and I am on the other side. Let me show you how I got here.’” says Stucky.

Peek agrees. “Most peer recovery coaches have lived experience in addiction,” he says. “When I get called to the hospital, and someone comes in with a drug addiction problem, I tell them that I am in long-term recovery: ‘I’ve been there and know what it’s like,’ and that makes a big difference to that person.”

People with SUD are often aware of the stigma or lack of trust that surrounds them. Doctors often do not trust those with SUD because they may believe that they might be shopping for more substances. “A lot of time, they [people with SUD] don’t trust doctors and nurses to tell them what’s going on,” says Peek. So, they often open up willingly to these coaches, sharing more information about their physical and mental health. Peek, in turn, can share this information with doctors and nurses and connect these folks to detox centers and residential treatment centers. Bloomington’s Stride Center also employs a peer recovery approach.

While some places, such as the Stride Center and Indiana Center for Recovery, stayed open during the pandemic, many peer recovery options moved to telehealth. “We had to adapt,” says Peek. “Addiction never shuts down, and people don’t stop using.” So Peek did telehealth with the majority of his approximately 135 patients.

THRIVE partnered with other providers to get telehealth to connect people with their providers using tablets and headphones. “Peer recovery coaches would go to a client’s house and let the client use the tablet while wearing headphones to preserve HIPAA rights,” says Stucky. “Staff would not stay in the room, and the client would be in a secluded room for their session.”

Harm reduction

Harm reduction is a strategy aimed at reducing the adverse outcomes of drug use. It’s a pathway that the Stride Center firmly embraces. “We are in the business of keeping our guests safe, and we are not unrealistic that they’re going to come here to quit using, cold turkey,” says Harrington. As part of the strategy, medication-assisted treatments (MAT)and other psychosocial interventions successfully move a person with SUD toward long-term abstinence.

Jackie Daniels, vice president of communications at the Indiana Center for Recovery, says harm reduction ‘allows people to stay alive until they determine what will work for them in the long term.’ | Courtesy photo

However, harm reduction can be controversial because many people do not think it is on the recovery spectrum, says Daniels at the Indiana Center for Recovery. “It’s important for me,” Daniels says, “because harm reduction is what a lot of times allows people to stay alive until they determine what will work for them in the long term. Besides, a person with an opioid addiction who is dead cannot seek help.” So all recovery options, including abstinence, are critical, she says.

Essentially, if a person is addicted to substances but wants to get off drugs, they have two options. One is to abstain from using a program like Bloomington’s Indiana Center for Recovery that promotes abstinence and has medical detox teams and a detox center to support this process.

The other option for recovery is MAT, using medications like buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone. The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 gave doctors the prescription authority with these drugs for treating opioid use disorder (OUD). Providers must see the patient in person to prescribe buprenorphine. However, they must first complete training and then obtain what’s called an “X waiver” from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency. Once they have an X waiver, physicians initially prescribe to only thirty patients, although they can increase their number to 275 patients so long as they complete their annual reporting requirements with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The problem: a shortage of physicians willing to prescribe MAT. A 2017 White House Commission Report found that 72 percent of rural counties had no doctors who could prescribe buprenorphine even though studies show that these medications cut the mortality rate by 50 percent and keep people in treatment longer.

A recent Indiana University study also found that the number of physicians with waivers were disappointingly low but especially low with primary care physicians who worked in a healthcare system. Physicians with waivers were also less likely to practice in high-poverty areas.

For Anwar, this is particularly frustrating because the stigma impacts MAT availability in rural communities. “Providers do not want to address and attract them [people with OUD] to their practice,” says Anwar. “Some providers think that this is a moral weakness and that the treatment is replacing the drug of choice for another drug.”

(l-r) Case Manager Brenton McQueary with Daniels at the Indiana Center for Recovery. | Courtesy photo

However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the DEA temporarily relaxed its requirements, making it easier for physicians to prescribe to new patients by telephone, email, and telehealth and encouraging electronic prescriptions to continue until the public health emergency ends. Anwar hopes that the relaxation of restrictions will increase the number of physicians who will obtain the X waiver to prescribe MAT. Still, getting providers to participate in MAT, says Anwar, has been very difficult in rural Indiana.

To reduce opioid overdoses, many places have installed NaloxBoxes to provide ready access to the drug naloxone hydrochloride, which blocks or reverses the effects of an overdose. Since overdoses have been on the rise since the pandemic began, THRIVE started placing NaloxBoxes in Scott County and other counties for easy access and for anyone to use. Naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan, is available at most major pharmacies without a doctor’s order.

Syringe service program

When the HIV epidemic hit Scott County, one of the recovery efforts included a syringe service program (SSP) that opened in 2015. A syringe service program provides clean needles to people with OUD. They can use the needles and then return them for sterile needles. It is part of harm reduction’s continuum of recovery services. Under a 2015 Indiana law, the state legislature left it to local elected officials like county commissioners to decide on the placement of an SSP in a community.

The front window display of the Stride Center at 312 N. Morton St. in Bloomington. Susan Harrington, program manager at the center, says Stride is a voluntary diversion center and ‘resource hub.’ | Limestone Post

SSPs prevent new infections while also saving money. Right now, the estimated lifetime cost of treating HIV is approximately $450,000 per person. Nationwide, treating substance-use infections (from using dirty needles, for example) is $700 million annually. The cost of a syringe service program serving 250 clients is $400,000, of which only 1.6 percent is start-up cost. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, as of April 2021, SSPs are operating in 42 states and D.C. In Indiana, only eight programs are in operation, one in Bloomington.

Since Scott County implemented a syringe services program, HIV infections dropped to one case in 2020. According to an IU School of Public Health report, “The Implementation of Syringe Services Program in Indiana,” the Scott County SSP was estimated to “save Indiana taxpayers approximately $120 million in costs associated with treating those with HIV.” However, in February, two of the three Scott County commissioners voted to shut down the program by January 2022. Despite Stucky’s efforts to keep the program running, this move devastated the Scott County recovery community.

A Brown University study reflects precisely just how devastating the blow could be. In the study, Brown University researchers simulated what would happen in rural areas, specifically Scott County, if the SSP was permanently closed. They found that the SSP program was working in Scott County, but without the program, the county could expect 176 infections over five years among persons who inject illicit drugs.

Since no functional substitute for an SSP exists, Stucky and his community must develop replacement options. Will it mean returning to 2015 when harm reduction coalitions got together and started passing out clean needles? “I don’t want it to come to that again because an abundance of needles was littered,” says Stucky. “But it is a lot better than having nothing and going back to the numbers we had in 2015.”

Educating through Project ECHO

During the opioid epidemic, Lembke, the Stanford University physician and author, was struck by the harm being done to patients by highly educated, well-intentioned, and very smart doctors who were, quite simply, practicing bad medicine. She wanted to get to the bottom of why this group bought hook, line, and sinker into the idea that the chance of addiction was very, very low. So, she wrote her book Drug Dealer, MD.

There is no question that OUD conditions are complex and often chronic, especially in rural and underserved areas. Sure, doctors were duped, but doctors, too, needed more information on treating these complicated conditions. One way to address this deficit has been Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes).

At Indiana University, Opioid ECHO for OUD began in 2018 as a partnership between primary care providers and the IU School of Medicine. The goal: improving the treatment of OUD in rural and underserved areas. Started at the University of New Mexico in 2003, Project ECHO began by linking specialists treating hepatitis C with primary care specialists through teleconferencing, and this guided practice model took off.

With a guided practice mode, clinicians share knowledge with other clinicians and providers using a hub-and-spoke method. Experts from academic medical centers or larger hospitals form the hub. The spokes are participating healthcare providers.

Here’s how Opioid ECHO works. According to Jon Agley, Ph.D., deputy director of Prevention Insights at the IU School of Public Health, OUD experts include a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a lawyer, a pharmacist, and other addiction specialists. Through Zoom video conferencing, healthcare providers across the state and nation listen to a brief lecture on new treatments, medication, and rules on OUD. Then a participating primary care provider shares a complex case, and the experts workshop it.

Here’s how Opioid ECHO works. According to Jon Agley, Ph.D., deputy director of Prevention Insights at the IU School of Public Health, OUD experts include a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a lawyer, a pharmacist, and other addiction specialists. Through Zoom video conferencing, healthcare providers across the state and nation listen to a brief lecture on new treatments, medication, and rules on OUD. Then a participating primary care provider shares a complex case, and the experts workshop it.

Input is shared back and forth. Experts do not make recommendations on cases but offer insights on past workable solutions. “The premise of ECHO is that if you want to build specialization, expertise, and disseminated it widely to rural and underserved areas, the virtual case-based learning where everyone works together to manage a complex case is a promising approach,” says Agley.

Since Opioid ECHO began, Agley believes it has granted more than 1,770 person-hours of continuing education and training — one solution to improving care for OUD. Nationally and internationally, 44 countries have used 920 ECHO programs with 424 global hubs to address various medical conditions.

The unknown question is how or if it is possible to resolve the opioid epidemic. Communities faced with these issues will need to refocus their efforts in managing what is now, for them, a public health crisis in the middle of a pandemic. But most are resilient and committed.

Cooke says it best: “If I knew then what I know now, I don’t know if I would have done it. But I am really glad that I have gone through that. … I feel like I have purpose and meaning. … It was a very difficult year. But I think having gone through the HIV outbreak informed the community and me that we can work together and that there will be a light at the end of the tunnel.”

The most important thing that we can do, he says, is to take care of each other.

Want to read more on the opioid epidemic? Check out these books.

Canary in the Coal Mine, by William Cooke, MD. Tyndale Momentum, 2021.

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and The Drug Company that Addicted America, by Beth Macy. Back Bay Books/Little, Brown and Company, 2018.

Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic, by Sam Quinones. Bloomsbury Press, 2015.

Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It’s So Hard to Stop, by Anna Lembke, MD. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, by Patrick Radden Keefe. Doubleday, 2021.

Pain Killer: An Empire of Deceit and the Origin of America’s Opioid Epidemic, by Barry Meier. Random House, 2003, 2018.

More resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Indiana Rural Opioid Consortium

Indiana University Opioid ECHO Project

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT), research brief by the IUPUI Center for Health Policy Studies

Syringe Service Programs (SSP)

— Monroe County Syringe Service Program

— Key Resources from HIV.gov, including federal funding

— NASTAD guidelines to implement SSPs for state and local health departments (National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors)

— Modeling Study of Scott County Indiana SSP (Brown University)