In 2016, a survivor of sexual assault had a physical evidentiary exam, known as getting a rape kit, at IU Health Bloomington Hospital. While she says this process itself was consistently clear and well explained, the process of tracking the whereabouts of her kit afterward was less-so. A new law seeks to improve this process, with a system that allows survivors to track the status of their rape kits themselves, rather than having to go though detectives. | Photo by Nicole McPheeters

Unlike many other crimes, sexual assault leaves the survivor’s body a crime scene — one that cannot be sanctioned off with yellow police tape or protected by a barricade. Rather, the survivor must carry with them a literal body of evidence. To help the survivor obtain legal justice, and as long as the survivor feels it is safe to do so, experts say they should immediately undergo a process known as a physical evidentiary examination (also called a standard medical forensic examination), commonly known as getting a rape kit.

Kristyn Frisk is a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) at IU Health, where she routinely performs three- to five-hour evidentiary exams. Frisk makes sure each survivor knows they are in charge of their own exam by asking for permission to proceed at every step of the process. | Photo by Nicole McPheeters

Sexual assault can be a difficult experience to recount privately, let alone publicly. After being assaulted, the burden falls on the survivor to immediately report the crime to a stranger and undergo a complete examination of their body by yet another stranger. Then, despite these challenges, survivors must go through law enforcement any time they would like a status update on their rape kit’s location or test results. While a recent audit by the Indiana State Police found that nearly half of all untested rape kits in Indiana are considered Indiana’s “backlog,” a new law requires the Indiana Sexual Assault Response Team (ISART) to study a system of tracking rape kits to help with these issues and alleviate some of the tracking burden for survivors. Its findings are due in December.

There is no one response to sexual assault — one person can as easily seem calm while another can appear distraught or angry. A local rape survivor, whose identity will be kept anonymous for this story, had a rape kit collected in 2016 at the IU Health Emergency Department. She recalls being composed during her evidentiary exam.

“I can certainly see how it can be traumatizing for some people,” she says. “For whatever reason, I just wasn’t in that sort of headspace at the time. The nurse did a very good job of explaining what was happening at every step. There was always an element of choice, and I knew it was perfectly okay if I chose not to go on.”

Kristyn Frisk, a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) at IU Health Emergency Department, says it is important to establish trust and empower the survivor throughout the entire exam. “It’s incredibly intrusive to have someone taking photos of every body part after you’ve just been assaulted,” says Frisk. “I tell them, ‘What you are going through is horrible, control was taken away from you, but I am here with you now, and you get to choose how we move forward.’”

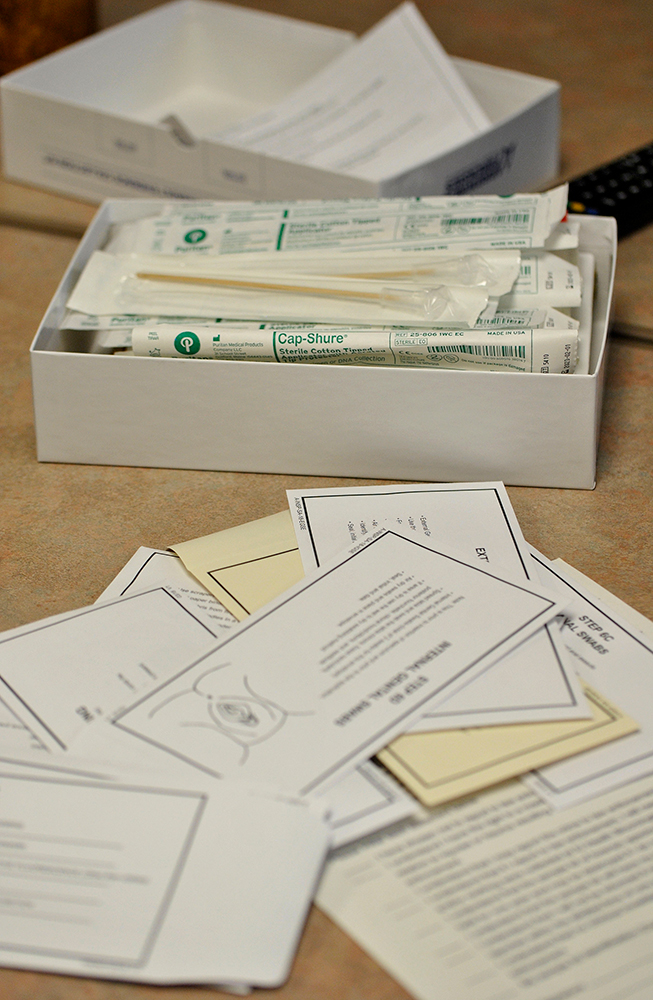

Rape kits are small white boxes containing forensic evidence and forms that a SANE fills out while performing a physical evidentiary exam. These forms include information on everything from evidence collected under fingernails to findings of an internal exam. | Photo by Nicole McPheeters

On average, the exam can take between three and five hours. In Bloomington, it is recommended that an evidentiary examination be done within 96 hours of the assault at either the Emergency Department at IU Health Bloomington Hospital or, for students affiliated with Indiana University, the IU Health Center. Exams are often completed by a SANE, a registered nurse who has received specialized education and fulfilled clinical hours working with survivors of sexual assault. Currently, nine SANEs on staff in the IU Health Emergency Department can perform this exam.

The exam begins with a swab inside the cheek to identify the survivor’s DNA against any other DNA that may be found. The survivor’s hair is combed and their fingernails scraped underneath for evidence. Toluidine blue dye and a blacklight can be used on skin to identify any unusual stains or markings invisible to the eye. Swabs are taken around the genitals, and an internal exam is done if the survivor is able and willing. Pictures are taken throughout the entire exam as proper procedure to further document evidence and possible injuries. Once carefully collected, everything is placed in a white cardboard box labeled for physical evidence recovery. This is what will be classified as the survivor’s rape kit.

SANEs can get additional certifications, SANE-A and SANE-P, for adults and pediatrics. Brandy Summers, a SANE-A at the IU Health Emergency Department, explains that a survivor can opt out of any portion of the exam — just being there takes a great deal of bravery.

“We have to ask a series of detailed questions so we know exactly where to collect evidence,” says Summers. “For example, if they were bitten or licked, we would have to swab those areas. It’s almost like we are re-victimizing them. It is so important that they know they are safe here, and that we ensure they are safe when they leave.”

Summers, who has been working with the SANE program since 2010, chose to pursue continued education beyond the standard certification required of a SANE. As a SANE-A, she continues to perform evidentiary examinations but also has a role collaborating with advocacy groups within the community. Middle Way House, for example, will train volunteers to act as On Scene Advocates (OSA) to offer emotional support to survivors while they undergo this examination. Before beginning an exam, a SANE will offer each survivor the option to have an OSA present.

Yael Massen, an OSA with Middle Way House, stresses the importance of recognizing the impact of the crime while also treating the survivor as just that — a human being who has survived an unthinkable offense. “Oftentimes, survivors are in shock and don’t have a way of fully articulating their experience,” Massen says, adding that survivors come from all walks of life. “You never know who it could be waiting in that examination room. It could be a grandma, a student, or a mom with three sleeping kids. We have to meet them where they are.”

Brandy Summers, a SANE-A at IU Health, pursued further education and experience to gain an additional certificate to work with adults who have survived assault. Summers also works with advocacy groups throughout Bloomington. | Photo by Nicole McPheeters

Each case has its own set of circumstances, based on the different lives of each individual. Survivors in Indiana have the choice to report the crime under the Jane Doe Law, which allows them and their rape kit, also referred to as a sexual assault kit (SAK), to remain anonymous. These anonymous SAKs offer the survivor direct access to medical care and allow important evidence to be collected, without pressing the survivor to immediately decide whether to report the assault to law enforcement. This allows the survivor to control the level of engagement they may have with the criminal justice system. While a SAK remains anonymous, it is not sent to the Indiana Crime Lab in Indianapolis for testing. However, a Jane Doe has one year to change their mind. According to Indiana law, an anonymous kit is legally required to be kept by the presiding law enforcement agency for one year before being destroyed if a survivor does not come forward.

Alternatively, if a survivor has chosen to report with the police, their SAK is classified as non-anonymous, or known. It is worth noting that regardless of the SAKs status of anonymous or non-anonymous, law enforcement will never disclose the survivor’s name to the public. Non-anonymous SAKs are tested only if the crime has been reported to law enforcement and the prosecutor has determined the kit should be tested. There is no statutory requirement in Indiana requiring law enforcement to test all SAKs that are collected. Nor is there a centralized tracking system in place to assist in counting the number of untested SAKs within the state.

It was not until 2017, when the Indiana General Assembly passed Senate Resolution Number 55, that the Indiana State Police were required to conduct a thorough audit of all untested SAKs within the state. With the cooperation of 91 of the 92 Indiana counties, the audit uncovered 5,396 untested kits in the custody of law enforcement. Of those, 416 were anonymous kits, 1,669 were attributed to no crime/false reports, and 751 were decided cases. The remaining 2,560 SAKs are considered Indiana’s “backlog.”

According to the National Center for Victims of Crimes, the amount of time needed to process a SAK varies widely by jurisdiction. Processing a SAK is a multistep process where each step is conducted systematically in an effort to avoid mistakes. It is possible for a high-priority case to be processed in as little as two to five days, although three to six months is more typical. Unfortunately, some crime labs may take up to a year or longer to test a SAK. This delay, or backlog, can often be a result of funding constraints, which limit a lab’s ability to maintain adequate staffing, purchase updated or more modern equipment, and keep pace with testing requests.

Our anonymous source chose to report with the police, so her SAK was classified as non-anonymous. She does not know the exact length of time from when her rape kit was collected to when she was notified of the test results but guessed it was within a couple months. She also recalls parts of the process that were never clarified.

“There are some things you just don’t think to ask at the time,” she says. “For example, I gave them my clothes in the exam so they could test them for DNA. I didn’t know they would not be giving [them] back.”

Before each evidentiary exam, assault survivors are offered to have an On Scene Advocate (OSA) accompany them throughout the process. Yael Massen, an OSA for Middle Way House, provides emotional support to survivors during the exam and goes through the options and actions they can take following the exam, if they so choose. | Photo by Nicole McPheeters

Kristen Pulice, chief operating officer at Indiana Coalition to End Sexual Assault (ICESA), explains that despite the challenges of undergoing a physical examination, information regarding the non-anonymous SAK is not easily accessible to the survivor.

“For the SAKs that are tested in Indiana, there is no current tracking system in place. A survivor would need to contact the prosecutor’s office or an assigned detective to inquire,” explains Pulice.

Our anonymous source confirmed this process. She had to contact a detective when seeking information on the status of her SAK in the weeks following. “The detective was very good at providing me with information and answering most of my questions, but she was not trained in DNA testing,” she explains. “There were some questions she just could not answer. I was told there were mixed DNA fragments in a few areas that had been swabbed during my exam, but they were insufficient to analyze. I assume that ‘mixed’ meant multiple individuals’ DNA, but neither I nor my detective were sure. I also asked if they knew how the fragments were insufficient for analysis, and she did not know.”

In efforts to provide survivors with better access to this information, Senator Michael Crider, a Republican member of the Indiana Senate, with the help of several advocacy groups, authored Senate Bill 264, which was signed into law in March. It requires the Indiana Sexual Assault Response Team (ISART) to research the creation of a tracking system and designate an appropriate agency to create and manage the system. ISART is also required to identify resources necessary to develop and fund the system. If successful, the tracking system will provide survivors with direct access to the status of their SAK without the need for a go-between.

Pulice says her organization “supports Senator Crider and the efforts to bring survivors transparency and the ability, on their own terms, to bring control and security back into their lives while also requiring the accountability of the systems engaged in the process.”

This law requires ISART to submit a report to the Legislative Council by December 1. If successful, the tracking system could alleviate some of the burden that falls predominantly on the survivor to seek answers and results.

Our anonymous source believes the law could offer a helpful resource for survivors during the difficult aftermath of an assault.

“I was never contacted with information about my kit,” she says. “If I hadn’t had a specific person to call, I don’t think I would have thought to follow up on anything or even been able to if I had. Having direct access to this information would have certainly been helpful.”

Nicole McPheeters contributed to this reporting.