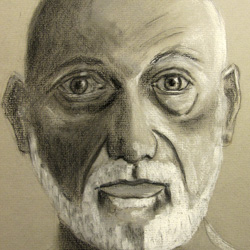

Local art lovers are anticipating the opening in April of FAR Center for the Contemporary Arts at Fourth and Rogers. Pictura owners David, left, and Martha Moore are doing more with FAR than moving their photography gallery into a historic building — they’re on a mission to “create a different experience” by bringing different kinds of art together. | Photo by Chaz Mottinger

On Bloomington’s Near West Side, a spry nonagenarian is undergoing a facelift — a new look for a new role, wedding aesthetics, education, and social interaction. David and Martha Moore, owners of Pictura Gallery, are repurposing an old grocery at the southwest corner of Fourth and Rogers streets into the FAR Center for the Contemporary Arts. When it opens in April, they hope you’ll call it FAR.

As they collaborate with a wide range of artists to offer exhibitions, installations, and performances, they’re certain this new, larger space will let FAR take on a life of its own.

“We just know things are going to happen in that space,” Martha says. “Great things are going to happen that we can’t even imagine yet.”

Construction, which started in June 2017, is on schedule.

“On the First Friday Gallery Walk in April 2018, we’ll cut the ribbon and invite the public in,” David says. That date honors the tenth anniversary of the opening of Pictura on the Courthouse Square. The old gallery hosted its final First Friday on December 1 and went dark a few days later. The staff remains busy with the move and planning exhibitions, but visitors must wait until April 6 for their Pictura fix.

FAR, located on the corner of Fourth and Rogers, will open for the First Friday Gallery Walk on April 6. | Image courtesy of Malane Benedetto

Built in 1925 as a grocery store and later serving as a parking garage for police vehicles, the building’s 5,000 square feet have been thoughtfully reconfigured by Lauren Bordes and Evan Cerilli, architectural designers and co-founders of the New York City firm Malane Benedetto.

If 1925 feels fuzzy, imagine yourself back in the Roaring Twenties with its flappers and Prohibition-era gangsters, when everything is the “bee’s knees.” In 1925, Harold Ross launches The New Yorker magazine, F. Scott Fitzgerald publishes The Great Gatsby, and Adolph Hitler unleashes Mein Kampf. A Tennessee jury convicts John Scopes of teaching evolution. Congress authorizes the sculpting of Mount Rushmore. The first talking movie is still two years away, but you can catch Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush, Lon Chaney in Phantom of the Opera, and Oliver Hardy as the Tin Woodsman in the original The Wizard of Oz. You can buy a Model T Ford for $260 or spring for the upscale Chrysler Six at $1,565. For $2,570, you can purchase Sears & Roebuck’s “The Homewood,” a precut kit for a six-room bungalow.

The FAR building was built in the 1920s as a grocery store and later became a parking garage for police vehicles. | Photo by Chaz Mottinger, courtesy of Pictura Gallery

Bloomington hovers midway between its 1920 population of 11,595 and 1930 census of 18,227, all within 10 or 12 blocks of the Courthouse. In the first Old Oaken Bucket game, IU and Purdue grunt to a 0-0 tie. Most nights, you can find Hoagy Carmichael playing piano and crooning at the Book Nook on Indiana Avenue.

At Fourth and Rogers, Roy Burns opens a grocery to serve the growing Prospect Hill neighborhood. Ninety-three years later, his red brick structure has history’s stamp of approval, a listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

While incorporating contemporary features and materials, the design respects the structure’s monumental scale and historical uniqueness. Commissioned by the Moores to imagine the art gallery of the future, Bordes took her cues from the past.

Architectural designer Lauren Bordes is using the original brick, tresses, steel, and wood of the garage in her design for the FAR theater. | Photo by Chaz Mottinger, courtesy of Pictura Gallery

“We looked to the existing plan — we got to tour the building,” she says. “We cared a lot about allowing the natural logic of this old structure to inform the future spaces we created.”

She left the garage, with its steel bow trusses that span vast spaces without columns, relatively untouched. The bricks will be cleaned and whitewashed, but this huge bay remains raw. “When you see the original brick, the original bow trusses, structural steel, and wooden ceiling, you register its age and history.”

Walk with David and me through the unfinished building. Let the whine of circular saws and the rhythmic rapping of hammers assault your ears. As sawdust floats through beams of sunlight, let the fragrance of fresh-cut pine fill your nostrils. Although you can see through most of the 2-by-4 walls, notice how the framing clarifies the four spaces.

The garden will look west into the library. A pergola covers part of the garden, above entrances to the library and atrium. | Image courtesy of Malane Benedetto

At 1,700 square feet, the new Pictura slightly exceeds the old gallery’s 1,400. When its high-finish drywall, coffered ceiling, and gallery lighting are complete, it will exhibit the clean, minimal look of contemporary galleries. As we walk across the atrium to the library, notice how its curved west end evokes the nave of a cathedral.

Excitement bubbles up as David describes how the highly stylized doors that open from the library into the garden will offer visitors a line of sight from Rogers Street to the library’s west end.

David sees movement going the other direction, with events spilling outward onto Fourth Street. “I think — working with the City, of course, getting the right permissions — we’ll be able from time to time to have, like, a street fair. That makes us really excited about this corner.”

The 12-foot doors on the Fourth Street side of the theater create the potential for indoor-outdoor events, like street fairs. | Image courtesy of Malane Benedetto

The garden posed a challenge. Most people don’t perceive outdoor areas as spaces unless they are clearly framed, Bordes explains. That framing comprises a metal extension that harmonizes with the Rogers Street facade and a gate to offer privacy for the garden. Steps lead from street level to the garden’s wooden deck with planters, a green wall, and a pergola over the library and atrium entrances.

‘We’re no longer the west edge’

The Moores’ enthusiasm for FAR is contagious, but people with no connection to the project also consider it important.

To start with a neighbor, preservation developer Cynthia Brubaker says, because she’s already doing many of the things the Moores envision at the I Fell building across the street, the two arts centers will create symbiosis. Launched in 2012, Brubaker’s center rents studio space to more than 20 artists plus Rainbow Bakery. The 1930 structure, built originally as a luxury-car dealership, also houses two galleries, which feature poetry readings, musical happenings, and video events as well as exhibitions.

Cynthia Brubaker, who has worked on many historic preservation projects, including Middle Way House and I Fell, says the neighboring I Fell and FAR will benefit from each other. | Limestone Post

Brubaker, who earned a master’s in historic preservation from Columbia University, has been the force behind numerous Bloomington redevelopments, including Middle Way House.

I Fell “has stretched the boundary of the downtown commercial arts scene in an organic way and by using a historically commercial building,” she says. “The Moores’ project is important for continuing that pattern, thereby validating the efforts of the artists, entrepreneurs, and patrons drawn to the intersection of Fourth and Rogers.”

She sees her new neighbor as an extension, not competition. “People will visit FAR, then come to see what’s available at I Fell and vice versa.” Regarding First Friday Gallery Walks, she likes the fact that “we’re no longer the west edge.”

Stroll a few blocks north and east to City Hall, where Sean Starowitz, one of three assistant directors in economic and sustainable development, works on leveraging arts and culture to improve Bloomington’s economy and quality of life.

“I think it’s huge,” Starowitz says about the impact of FAR. “It’s one aspect of the Bloomington arts landscape that we’ve been missing for a long time. They’re filling a huge void here — that multipurpose, multi-use contemporary art space.”

Economic development has shifted in the past 15 years. “It’s not about chasing smoke-stack industries anymore,” he says. “It’s about the quality of place and experiences. So, making sure that you have rail-to-trail programs, that you have arts and culture festivals like Lotus, that you have a flock of restaurants and coffee shops and a variety of experiences for people to engage in, and, of course, good schools.”

Brubaker says FAR is important for “validating the efforts of the artists, entrepreneurs, and patrons drawn to the intersection of Fourth and Rogers.” | Limestone Post

Starowitz likes to talk about the Rule of Ten, which holds that having ten places to visit or ten things to do attracts more visitors. He’s certain FAR will seriously ramp up Bloomington’s Rule-of-Ten profile. “It’s going to be really, really exciting for the community.”

He anticipates FAR will incubate business growth in the neighborhood, possibly including a restaurant, while anchoring a Fourth Street arts corridor.

As Martha and her colleagues began plotting the map for their 2018 brochure, she discovered, “When you look at where all the galleries are located in 2018, there isn’t a circle anymore.” The route has become almost linear from Gabe Colman’s The Venue at Fourth and Grant through Ivy Tech John Waldron Arts Center, the Blueline Gallery, and I Fell. It stretches slightly north to the By Hand Gallery and Gallery 406 on Kirkwood and slightly south to the Bloomington Convention Center on Third. FAR will soon anchor its west end.

‘High school sweethearts’

After Martha’s father died when she was ten, her mother moved Martha and her brother from Northfield, Minnesota, to Bloomington, Indiana, where their grandparents helped raise them. Martha’s Indiana University roots run deep. Her grandfather Leon Wallace was dean of the IU School of Law. Her mother, an IU School of Journalism graduate, was managing editor of the IU News Bureau. Martha earned her bachelor’s in elementary education from IU. When Martha and David’s son, Andrew, graduated from IU, Martha proudly notes, he became the fifth generation of her family to do so.

David’s family moved to Bloomington in 1972. Later, at Bloomington High School North, he started photography as a hobby. In the U.S. Air Force, he worked as a Serbian-Croatian linguist for the National Security Agency.

The Moores believe “Spaces make things happen.” | Photo by Chaz Mottinger

David and Martha became high school sweethearts in the youth group at St. Mark’s United Methodist Church in the 1970s. They married in June 1981 and moved to Cleveland, where David graduated from Case Western Reserve University with a bachelor’s in biology. Martha taught remedial reading and earned a master’s degree at Cleveland State University.

Twenty years ago, the business passed to four siblings. Now, David works as director of strategic planning and secretary of the board of directors. CarDon owns or operates centers in 20 communities across central and southern Indiana, including Bell Trace on East 10th Street in Bloomington.

A comment heard in Antarctica

Join us for a conversation in David’s office overlooking the Courthouse Square. The burgundy walls are hung with his personal photography collection, ranging from such classics as Robert Doisneau’s 1950 “The Kiss In Front of City Hall” to contemporary abstractions by the Starns twins. The furniture is funky eclectic. On his desk, an oaken chest showcases his collection of fountain pens. As David nurses a mug of coffee, he and Martha sink into an overstuffed couch. Let’s start with the question “Why?”

The Moores have clear ideas about why they’re creating FAR, from legacy to barrier busting, education, demographics, and endowing the arts — and even to a comment heard in Antarctica.

The room facing Rogers Street will be the Pictura Gallery space. | Photo by Chaz Mottinger, courtesy of Pictura Gallery

David has just passed one of those birthdays with a zero in it. A few years ago, anticipating 60, he began thinking about the future. “We opened Pictura on my fiftieth birthday,” he says. “Every year, when your lease comes up, you’re constantly evaluating: Do I want to keep doing what I’m doing? We were constantly experimenting. So, it doesn’t feel like a huge leap of faith, frankly. It just feels like what comes next.”

Martha nudges the age discussion to retirement. “Looking ahead to the next decade and thinking would we want to close the gallery, and say, ‘That was great fun. What a great run we had!’?” As an alternative, they chose to “create an arts entity that would promote collaboration and photography even after we retire — a legacy kind of thing,” she continues. “What do we want our contribution to the photographic arts and to the arts scene in Bloomington to look like when we’re not actively in it anymore?”

The Moores will continue to strive to bring a variety of different types of artists together in one space with the new Pictura Gallery location. | Image courtesy of Malane Benedetto

When they opened Pictura, David admits to being naive in expecting there would be an art market in Bloomington solely because IU employees offered sophistication and disposable income. He discovered the market is segmented into smaller markets oriented to photography, sculpture, painting, pottery, music, theater, dance. Those segments rarely interact. “We have a lot of photographers who come into Pictura,” he says. “But we don’t have a lot of musicians who come in. We don’t have a lot of theater people.”

David, who does strategic planning for his family firm, applied that skill set to the party experience. “If the market is segmented,” he says, “I thought, ‘Well, maybe I can bring different aspects of the market together.’ So, I’m very interested in exploring over the next few years: Can I take music and combine it with photography and create a different experience for the viewer? Can I take the spoken word and combine it with photography and create a different experience for the participants?” He’s on a mission to break down barriers, to shatter silo thinking, to expand his audience.

The Moores plan to expand their educational programming with a new library space. | Photo by Chaz Mottinger, courtesy of Pictura Gallery

Martha, the retired teacher, loves FAR’s educational mission. “There were really two things we wanted to do when we opened Pictura,” she says. “We wanted to bring in the very best contemporary photography. But the second piece has always been education — how can we help people understand what makes a good photograph?

“It’s one thing to say to someone this is the best contemporary photographer we could find,” she continues. “It’s another thing for the person viewing it to understand why that photograph’s important. Or why it’s well done.”

Bordes designed education into FAR’s fabric. “Now we have a space dedicated specifically for an artistic lecture, photographic talk, presentation, projection,” David says. “We’re calling it a library, but it’s also a classroom. It seats about 40 people very comfortably. Very much designed for an intimate talk.”

Part of the motivation is personal. After finishing college, the Moores’ son and two daughters all moved to Denver. “We think Bloomington is a great place when you’re an IU student,” Martha says. “And it’s a great place to raise a young family, but for those twenty- and thirty-somethings in the middle, it can be difficult.” She credits the Pictura staff, all in their twenties or thirties, with bringing “tremendous energy” to the discussion of how to attract that key demographic to FAR.

Of the educational space, David says, “We’re calling it a library, but it’s also a classroom.” | Image courtesy of Malane Benedetto

Then there’s the excitement of the uncertain. “What will end up happening in this space is so much more wonderful than anything we can tell you today,” Martha says. “When we opened Pictura, we thought we were opening a little store, and it ended up being so much more. We know if we create this space, great things are going to happen there.”

Expanding from photography to other arts represents a major change. “The space that is Pictura Gallery will continue to be photography,” Martha says. “But that doesn’t mean Amy Brier [a sculptor and co-founder and president of the Indiana Limestone Symposium] couldn’t come in and do a limestone sculpture show in the events space.”

“We have a vision for what we can do to promote photography in a bigger space like that,” Martha says. “But we also wanted to create a space that other artists could use for their vision. It will promote collaboration between all kinds of artists.”

While FAR will expand on the types of art it will feature, Pictura will remain focused on photography. | Photo by Chaz Mottinger, courtesy of Pictura Gallery

Asked if FAR isn’t more a gift to Bloomington than a business, the businessman in Moore insists it must be self-sustaining. He expects revenues from weddings to fund the building. During the peak seasons of May and June, September and October, wedding rentals take priority, he explains. The other eight months of the year, art exhibitions and performances get preference.

“If I can take those four months of the year and do weddings and charge the market rate,” he says, “I believe I can create enough revenue to cover expenses and also create some level of profit.”

These ideas had been swirling in the Moores’ heads for a while. They had even identified a potential location. But a conversation with Buffy Redsecker, chair of the International League of Conservation Photographers, during a visit to Antarctica in January 2016, precipitated action.

“‘Spaces make things happen,’” David recalls her saying. “And that was enough motivation to finish the purchase.” Although he thought he understood it then, as FAR comes together and its spaces promise ever new possibilities, he’s even more convinced. “As we’ve gone into the design, as we’ve gone into construction, I accept it more and more. It feels more true: Spaces make things happen.”

A rendering of FAR’s atrium. While FAR will host weddings during the wedding season, that revenue will allow them to support different artistic endeavors. | Image courtesy of Malane Benedetto

The arts boost Bloomington’s economy

Bloomington has long been a leader in arts and culture in Indiana. In 1994, it became the first Hoosier city to require that one percent of the budget of any new building goes to commissioning public art, Starowitz points out. It is the only city to have a full-time employee working on arts and culture. It has created the Bloomington Entertainment and Arts District (BEAD) and, through Visit Bloomington, actively works with Nashville and Columbus to promote Indiana’s ArtsRoad 46 program to make the region an arts destination.

The theater space will accommodate all sorts of events. | Image courtesy of Malane Benedetto

A 2012 report on Bloomington, titled “Arts and Economic Prosperity: The Economic Impact of Nonprofit Arts and Culture Organizations,” demonstrates the payoff for these efforts. Using 2010 data, the national organization Americans for the Arts reports that nonprofit arts and cultural organizations contributed more than $72 million to the city’s economy that year. This dwarfs the median $10 million at towns of comparable size and significantly surpasses the $49 million national median of all cities studied.

Among the report’s findings, nonprofit arts employment constituted 3,430 full-time jobs, almost 30 percent of attendees at arts events were out-of-town visitors, and each visitor who stayed overnight spent, on average, $156.69.

In a preface, titled “Where Culture Meets Commerce,” then-mayor Mark Kruzan writes, “A local government will be most effective in promoting sustainable economic growth by keeping a city livable; that is, making it one of the best places in the country to live, work, and visit. Our unique arts and cultural environment is a key aspect of that livability.” He cited the report “as proof that not only does arts and cultural activity have a civilizing, enlightening, and humanizing impact, but it also has a measurable and meaningful economic impact in Bloomington.”

FAR will soon be the newest member of the vibrant Bloomington arts scene. | Photo by Chaz Mottinger, courtesy of Pictura Gallery

Although not-for-profit status figures in the Moores’ long-term thinking, the currently for-profit FAR would not be included in any repeat of that report. However, that won’t stop it from being a vibrant part of Bloomington’s arts-and-culture scene.

The Moores have one parting message to those of you listening in on our conversation: Support the businesses that provide arts and culture to Bloomington.

“There’s a lot of things people in Bloomington love — like the Gallery Walk,” David says. “It’s important for people to give emotional support, but the galleries need financial support. They need people to buy their Christmas gifts. They need people to buy their birthday gifts — not from Amazon, not on a UPS delivery truck, not on their latest trip to New York City. They need people to buy their Christmas and birthday and graduation gifts here at the galleries. They need more than love.”

“A gallery walk isn’t just a night to have food and see great art,” Martha says. “Once in a while, you have to buy something.”