When my first child was three weeks old, she kinda died. The memory is still crisp and painful. I can still feel the hot air of the doctor’s office, hear the frustrated muttering of the nurse clipping and re-clipping the heart monitor on those adorable toes. I had pulled off her fuzzy, hot-pink socks to expose her little piggies, usually pink but today very pale. The pediatrician hurried into the room, white lab coat crisp and clean, her brow tightly knit in concern.

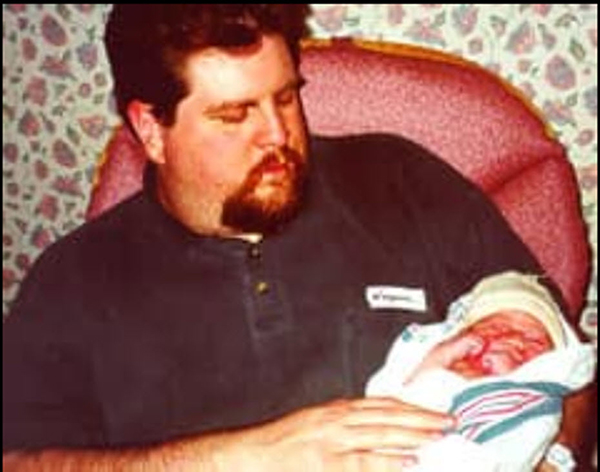

Troy sits with his newborn daughter. | Courtesy photo

“I can’t get the heart monitor to work,” the nurse said to the pediatrician.

The pediatrician held the baby’s toe in her giant fingers. “It’s not the machine,” she said. “There’s no pulse.”

Soon paramedics rushed into the cramped exam room with a full-size ambulance gurney. It seemed so ridiculous — this enormous contraption strewn with equipment — all for this tiny infant. A blink of an eye later, the siren’s wail gradually receded as the paramedics, my wife, the gurney, my firstborn, and the last of my sanity sped away inside the ambulance. I was suddenly left standing very alone there in the doctor’s parking lot, holding two very small hot pink socks, wondering where they were taking my girl and what horrible scary things were about to befall her.

The good news is that My Oldest is now 17 years old, vibrant, sassy, and healthy as a horse. She sailed through emergency heart surgery at 3 weeks old and her followup open-heart surgery at age 12. We were lucky to have good insurance and fabulous surgeons. Now she has cool scars and tells people she earned them in a sword fight.

Ironically, while My Oldest has recovered beautifully, I have not. I kept those doll-size hot pink socks in my pocket for six months, unable to part with them. They were an irrational comfort to me, a connection to that day and the feelings I had not yet fully processed. In times of stress, I would gently rub the fuzzy fabric, and it soothed me. Not sure how it helped, or why, but it did. Eventually, I stopped carrying them around and now they live in my sock drawer. I see them every couple of months and smile.

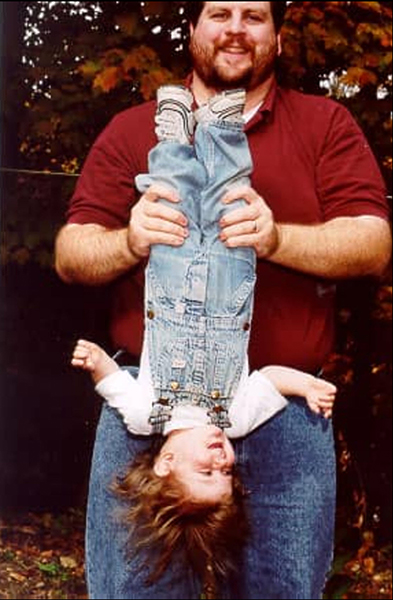

While his daughter “recovered beautifully” from emergency surgery, Troy says, he did not. | Courtesy photo

Your kids will challenge your limits, no fault of their own. Lucky for me, the universe chooses to test me regularly on this point. My youngest, Little Miss Thing, gave us a scare a couple years ago when a strep virus caused her kidneys to shut down for a day or two. Again, she’s recovered perfectly, but I didn’t fare as well.

I come unhinged when my kids are in pain, for which I won’t apologize. Helplessly watching your child experience pain changes you at a basic level. My mind still wanders back to that pediatric ICU, my tiny, helpless newborn wrapped in a thicket of tubes and wires. I remember thinking aloud that she had never cried such big tears at home. The on-duty nurse said, “She’s never felt real pain before.”

Heavy sigh.

The kidney episode wasn’t much better. Little Miss Thing was utterly miserable after five days in her hospital room, whining desperately and rebelling against her IV, her medicine, her low-salt diet. She was physically weak and mentally taxed, more than ever before in her short six years. Even a young child can only watch so many days of lame cartoons on the too-small hospital TV screen. She fought and wailed and cried big fat tears of frustration — and real pain.

Heavy sigh.

If you’ve ever wondered if your parents wanted to jump in, to take your pain away, to let you skip and play outside in the sunlight while they experienced your pain for you — I can assure that they did. I can guarantee you they begged God for the privilege.

Of course, we cannot and should not deny our children their pain. We humans have to experience these things for ourselves, feeling the joy of our victories and the despair of our losses. Our pain and our failures are the hot, cleansing fire in which our personalities are forged. Caution is good, but overprotective parenting makes children less prepared for the real world.

Science shows that typical, short-term childhood pains and defeats are critical to growth — and even that limited, temporary stress like sports competition and altercations are scary but also very likely to improve brain development and coping skills. Likewise, many doctors believe that early exposure to friendly microbes from dirt, friends and family, and, yes, even animal feces, helps kids avoid allergies and auto-immune diseases.

Troy’s oldest daughter had followup heart surgery at age 12. She tells people her scars are from a sword fight. | Courtesy photo

This summer, I transported Little Miss Thing to her first-ever full-week sleepover camp. She didn’t know a soul there, only that they were all Girl Scouts. This is one of those huge milestones for 8-year-olds, and one I had failed myself back in the day, sobbing and begging to go home.

As I drove, I prepared myself for the possibility she would change her mind, want to go home immediately. I knew I should be firm in encouraging her to stay. But, you know, not too firm. If she truly wanted to leave, I would oblige.

When we arrived at camp, she leapt from my car almost before it stopped, running all the way to the bunkhouses despite armfuls of luggage. She picked an empty cabin, announcing that whichever girls showed up to fill the other beds would be her “newest best friends.”

As she chattered about her big plans for the coming week, we dressed her bunk with the linens Mom had packed. Unfurling the fitted sheet, out came tumbling a misplaced pair of her soft pink knee-high socks. Little Miss Thing laughed and handed them to me. “I don’t need these,” she said. “I don’t need anything.”

A blink of an eye later, I once again stood alone in a parking lot, holding a pair of pink socks and wondering where my little girl was heading without me, what horrible scary things were about to befall her.

This time I smiled and climbed into my car for the long ride home, knowing she was strong, resourceful, and would have a great time.

But I kept the socks in my pocket for a few days, just in case.