[Editor’s note: This article was published in 2022, before the name of a zoonotic virus known as monkeypox was changed to mpox.]

For Graham McKeen, it’s déjà vu all over again. Little did he know that so soon after spending the past three years dealing with COVID-19 as the assistant university director of public and environmental health for Indiana University’s eight campuses, he would face another disease pathogen. This time it is monkeypox, and it is spreading rapidly. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that as of August 23 it is in 89 countries that historically have never reported monkeypox, and seven where it has been endemic. Twelve deaths have been recorded.

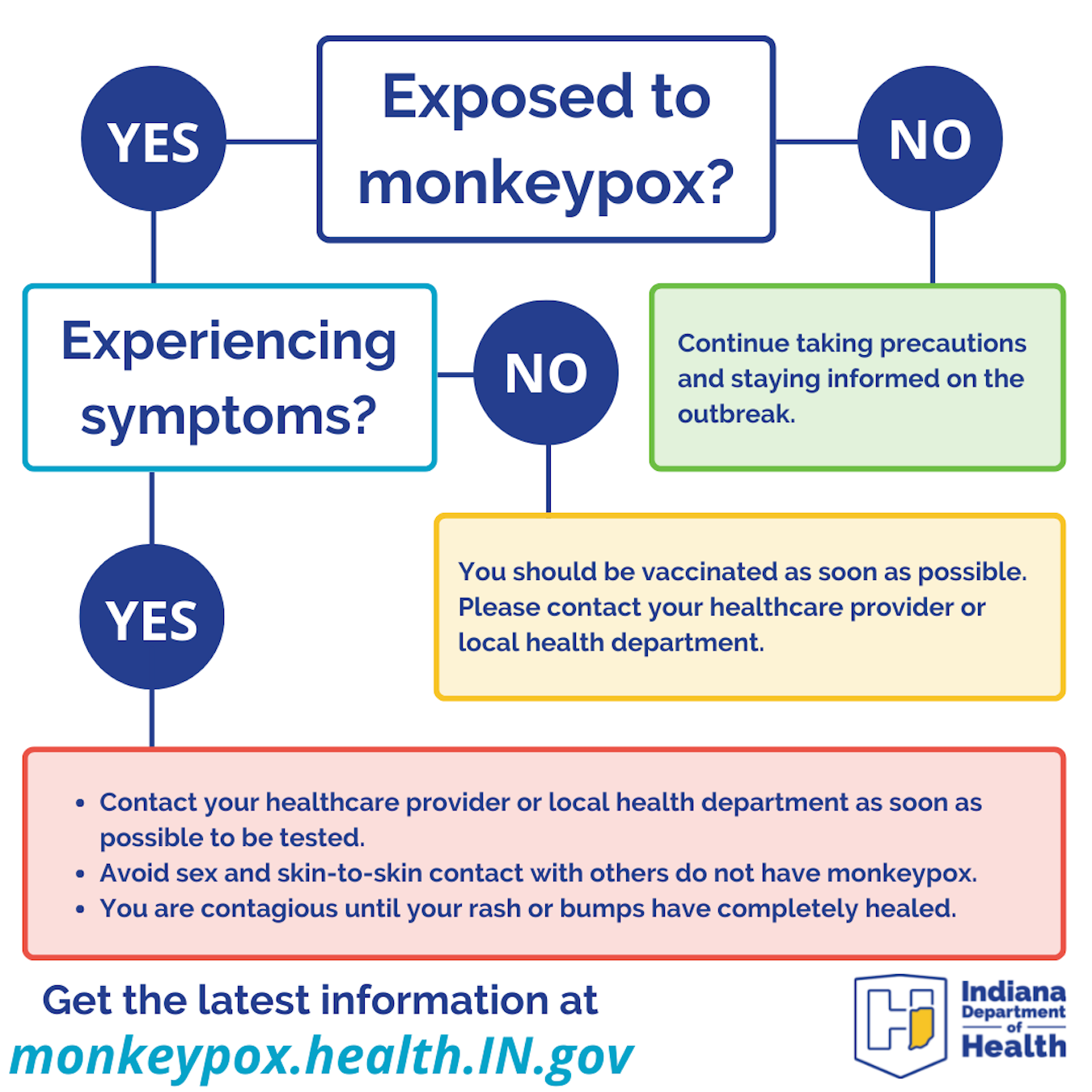

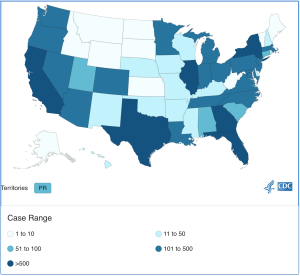

Case count by state, as of August 23, 2022 | Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

A zoonotic virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, monkeypox was first detected in humans in the 1970s in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sporadic outbreaks typically originated from wildlife reservoirs (meaning any wildlife that can be a carrier for a virus) where the monkeypox virus jumped from animals (in this case, rodents) to humans, making it a zoonotic virus. An article in The Journal of Infectious Diseases says monkeypox showed up briefly in the United States in 2003 when it infected 47 people in six states, including Indiana, with no deaths. That small outbreak was linked to pet prairie dogs.

As of August 23, there are 44,503 cases reported worldwide, 15,909 cases in the United States, and 134 cases in Indiana, according to the CDC. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency on July 15, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced one on August 4. The Biden Administration recently appointed Robert Fenton to lead the monkeypox response team in the U.S.

Declaring a public health emergency, which lasts 90 days but can be extended, means that the government can, for instance, offer contracts for treatment and supplies, scale production and availability of vaccines, expand testing capabilities, and make testing more convenient.

In Bloomington, according to the WastewaterSCAN dashboard, on August 18, a trace amount of monkeypox was detected in Bloomington wastewater. The WastewaterSCAN website says, “Detection of monkeypox virus DNA in wastewater solids indicates that there is at least one person in the community served by a wastewater treatment system who is infected with the virus and shedding its genetic material into wastewater.” WastewaterSCAN is a Stanford University initiative that monitors community wastewater for the coronavirus, monkeypox, influenza A, and respiratory syncytial viruses to help manage public health responses to viruses.

Why is this outbreak different?

The monkeypox virus historically was mostly limited to and contained in central and west Africa and didn’t spread quickly from human to human. But with increased travel, international conferences and meetings, and multiple-partner sexual encounters, the virus has jumped from Africa to scores of countries in other continents.

What epidemiologists and infectious disease experts are seeing is unusual. A New England Journal of Medicine article examined the international monkeypox cases from April to June 2022, which describes virus presentation, clinical causes, and outcomes. They found that the current global outbreak suggests changes in the biologic aspects of the virus and changes in human behavior (or both), as well as a waning smallpox community and relaxation of COVID-19 protocols, which may have contributed to this outbreak.

Graham McKeen, assistant university director of public and environmental health for Indiana University’s eight campuses. | Courtesy photo

As we encroach on wildlife habitats with changes in land use and the impact of climate change, says McKeen, these actions will, in turn, not only lead to a decrease in biodiversity, but we are also going to continue seeing more zoonotic spillover of viruses.

Monkeypox was detected again in the U.S. in mid-May 2022. But this monkeypox is also different, says Felicia Nutter of Tufts University, as quoted in a Futurity article. It has a sustained community transmission and does not present the classical description of monkeypox, in that it appears to come from a less virulent clade (or group), called the West African clade, or Clade II.

Symptoms of monkeypox include fever, headache, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, cough, and chills, along with a painful rash from pustules or blisters, typically occurring one to three days after a fever appears. According to WHO, the incubation period from infection to symptom onset is typically six to thirteen days.

How infectious is monkeypox?

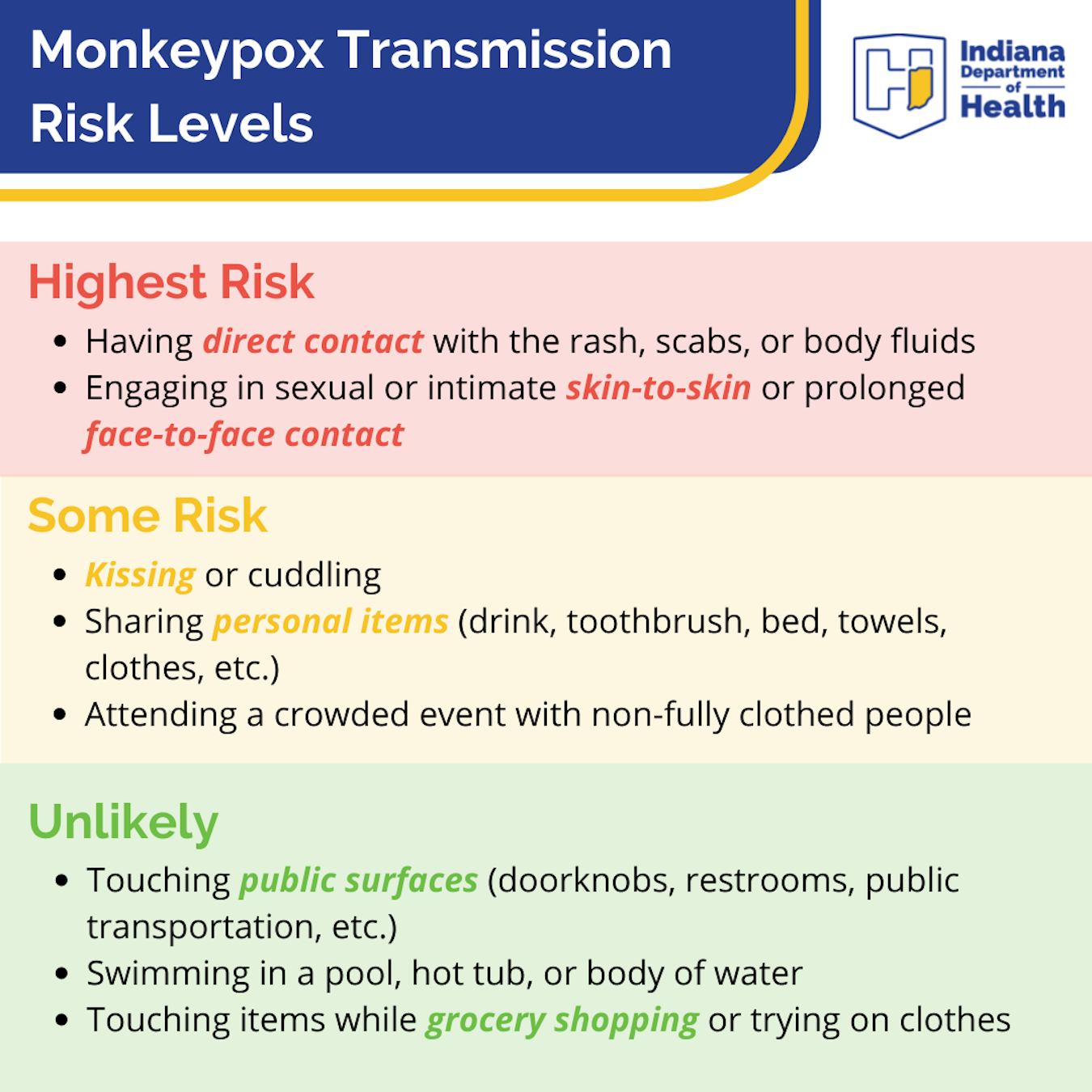

Exposure to monkeypox results when a person comes into close contact with an infected person, touches any clothing, bedding, or towels the infected person has used, or by respiratory droplets. Now, according to The Lancet, dogs too can get monkeypox.

Of the nearly 1,200 case reports received in July by the CDC, 99 percent of monkeypox cases were among men, and 94 percent reported male-to-male sexual or intimate contact during three weeks before symptoms occurred.

Monkeypox, however, is not classified as a sexually transmitted infection. Anyone in contact with someone who has monkeypox can be infected. A person is infectious until lesions scab over with new skin growth.

While monkeypox belongs to the same family of viruses as variola virus, the virus that causes smallpox, it is milder, says the CDC. Smallpox is a deadlier disease with a more virulent transmission rate than monkeypox.

In 1980, smallpox vaccinations were stopped when WHO declared smallpox eradicated. Until then, smallpox had a mortality rate of 30 percent. Today, people born after 1980 may be more susceptible to monkeypox because of the cessation of smallpox vaccinations.

Right now the testing mechanism for monkeypox is limited. The CDC recommends that most people who believe they are infected to see their primary care doctor. It’s challenging, says McKeen, because there is not a lot of testing available. “I don’t think many clinicians or providers are fully aware of monkeypox and how to test for it. It’s kind of new,” says McKeen.

Availability and effectiveness of monkeypox vaccines

Currently, two FDA-approved vaccines exist. The more promising vaccine is manufactured by Bavarian Nordic, a Denmark company, and is used for preventing smallpox and monkeypox in adults 18 years and older.

Currently, two vaccines have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Jynneos (also known as Imvamune and Imvanex) and ACAM 2000. The antiviral tecovirimat (a.k.a. TPoxx) used to treat smallpox is not FDA-approved to treat other Orthopoxvirus infections, such as monkeypox; however, the CDC holds a non-research expanded access Investigational New Drug protocol that allows use of tecovirimat for the treatment of monkeypox.

Approved by the FDA in 2007, ACAM 2000 is based on a vaccinia virus but has serious side effects and is generally only used by military personnel or persons who work with infectious diseases like smallpox and monkeypox. It is also much more complicated to administer.

The more promising vaccine, Jynneos, is manufactured by Bavarian Nordic, a Denmark company, and is used for preventing smallpox and monkeypox in adults 18 years and older. The FDA approved it in 2019. Generally given in two doses, Jynneos has recently been approved by the FDA to be administered in smaller amounts intradermally — under the skin, as opposed to deeper into muscle tissue, as with a typical flu shot, due to the low number of vaccines currently available. Jynneos can also be given post-exposure.

Research shows that even with the lower dose, the vaccine has been shown to be as effective as the two-dose administration even though Bavarian Nordic has expressed reservations about this direction.

Scan this code for the Monkeypox Vaccine Registration Form, or go to in.gov/health/ to learn more.

According to WHO, vaccinations against smallpox have an 85 percent effectiveness rate in preventing monkeypox.

To date, the federal government has distributed 700,000 vials of Jynneos. According to the Indiana Capital Chronicle, they will soon make 360,000 vials available for state health departments to order. Megan Wade-Taxter of the Indiana State Department of Health says Indiana has received 6,752 doses of Jynneos. “It is important to note that the number of doses that can be administered from that supply will increase under the FDA’s new emergency use agreement that allows for five doses per vial,” says Wade-Taxter.

Monroe County Health Department (MCHD) is currently looking into these lower dosage recommendations at this time, says Lori Kelley, the department’s health administrator.

MCHD has received only 20 doses of the Jynneos vaccine, Kelley says. “Due to the very low number of cases in the county and to protect privacy, specific case counts in the county are not being given at this time.”

Who is eligible for the monkeypox vaccine?

According to the Indiana State Department of Health (ISDH), the only persons eligible for the Jynneos vaccine are those who have been exposed to the virus or have immunocompromised health conditions. In addition, neither ISDH nor MCHD has a tracking mechanism to monitor the number of cases. Instead, says Wade-Taxter, “Because the vaccine supply is limited, we are working with partners to host clinics for at-risk individuals and close contacts.” ISDH has also established protocols for providers to request the vaccine if needed, and those protocols are posted at monkeypox.health.in.gov.

People born after 1980 may be more susceptible to monkeypox because of the cessation of smallpox vaccinations.

Now that students have returned to the IU–Bloomington campus, McKeen and his team are closely monitoring the situation. To date, approximately six cases have been located on university campuses nationwide. Though the American College of Health Associates emailed its members about monkeypox on July 28, it is still formulating guidelines for its members to follow. IU is a member of the association.

McKeen and his team have been meeting with IU infectious disease doctors and student health centers to discuss symptoms, clinical presentation, testing, and managing future referrals to current testing facilities such as the ISDH Lab and the Bell Flower Clinic within Eskenazi Hospital in Indianapolis.

According to McKeen, Marion County will set up weekly clinics over the next couple of months, and some places, like the Damien Center in Indianapolis, are offering vaccinations in Marion County. “In Monroe County, we have referral tracks to IU Health Positive Link and Monroe County Public Health Clinic for vaccination,” says McKeen.

Currently, MCHD is working with IU to ensure testing and vaccination needs are met, says Kelley. “Our strategy includes coordinated efforts with the university student medical center for needs.”

The IU COVID-Monkeypox Team

McKeen has been meeting with forty-chapter houses with congregate living, including fraternities and sororities, to discuss monkeypox, its symptoms, and university protocols. The student health centers, too, are critical in these discussions since, according to McKeen, most students will initially go to the student health center for care in the event of an infection. At the time of publication, IU had reported zero cases.

Now that students have returned to the IU–Bloomington campus, McKeen and other IU health officials have been meeting with infectious disease doctors and student health centers to discuss symptoms, clinical presentation, testing collections, and managing future referrals to current testing facilities. | Limestone Post

Even with zero-to-few cases, the university is taking monkeypox seriously. “We have an incident-team management structure,” says McKeen. “It’s a slim group considering how many people we have at university.” The group comprises Chief Health Officer Dr. Aaron Carroll, public health and safety representatives, an operations lead, and communications members. McKeen says it’s the same team they used for COVID-19 management. “We are the COVID-Monkeypox team over here,” says McKeen.

They meet every morning to discuss what’s happening on campus, looking for indications of the virus or the potential for outbreak and trying to identify outbreaks as they occur. As they continue to meet, McKeen says, the university understands that these viral outbreaks are no longer isolated events but are becoming the norm.

As a result, IU is moving from a temporary pathogen-to-pathogen response into a more permanent viral infection infrastructure within the university. “I think it will honestly be the direction we’re going globally,” says McKeen, “and we’ve kind of been in this structure for almost nearly three years.”

For McKeen, disease surveillance and public health preparedness have always been his job. Initially, it totaled 5 to 7 percent of his work time. He says it now takes up 90 percent or more of his job.

Will students isolate — and how?

What happens if a student gets infected with monkeypox? Isolating a student may be just as tricky as it was for isolating students with the coronavirus. The main message they are considering at this point, says McKeen, is that isolating on campus may not be the best idea. “I think that higher education will have to think about getting these folks home so they can isolate at home.

McKeen says, “In Monroe County, we have referral tracks to IU Health Positive Link and Monroe County Public Health Clinic for vaccination.” Both are at 333 East Miller Dr. in Bloomington. | Limestone Post

“We can’t put people on airplanes with monkeypox, but I think that’s definitely going to have to be the preference number one right now,” says McKeen.

Because monkeypox can be spread through person-to-person contact and through contact with bedding, clothing, and towels, infected students may need private and separate laundry facilities when isolated. For those students who have to isolate on campus, “we are really trying to look at if we can get isolation facilities that have their own contained laundry units,” says McKeen. “If we cannot do that, then I think we’ll be looking at services that can provide laundering to those in isolation for monkeypox.”

McKeen is meeting with residential housing representatives to discuss cleaning protocols used for the coronavirus in housing and isolation spaces.

As for remote learning options for isolated students, McKeen will confer with academic affairs to determine if this is a viable option. Monkeypox can be very painful and challenging to go through as a student, says McKeen. As a result, a student might need to consider withdrawing from that semester or taking an incomplete. “These are the questions that all institutions of higher learning must consider,” says McKeen.

Nonetheless, IU will be tracking positive cases of monkeypox as they occur through a non-public-facing reporting form and self-reporting as they have done with the coronavirus.

Bloomington Utilities wastewater testing

As some communities have seen, testing a city’s wastewater for viruses is critical in detecting the virus. Recently in New York City, wastewater management personnel found polio in its wastewater, and city health officials are now urging New Yorkers to vaccinate against polio if they haven’t been already vaccinated. Polio causes paralysis and death, and there is no cure.

Justin Greaves, assistant professor of environmental and occupational health at the IU School of Public Health, has been working with the City of Bloomington Utilities to establish a sampling regimen for city wastewater using digital polymerase chain reaction testing technology. | Courtesy photo

Vic Kelson, director of City of Bloomington Utilities, has been working with Justin Greaves, assistant professor of environmental and occupational health at the IU School of Public Health, to establish a sampling regimen for city wastewater. Bloomington has been testing wastewater for the coronavirus since 2020. They are now negotiating a sampling and testing regimen using dPCR technology, or digital polymerase chain reaction testing.

“The dPCR has the ability to monitor a wide variety of pathogens, including COVID and influenza,” says Greaves. “Previous reports have shown it to pick up monkeypox in wastewater.”

Greaves co-authored a paper, “Application of digital PCR for public health-related water quality monitoring,” that states dPCR can quantify genetic material from microorganisms with greater sensitivity, precision, and reproducibility than other tests. Typically, PCR methods are known to be fast. They can detect microorganisms that cannot be routinely cultured.

Kelson is optimistic. The city is partnering with MCHD, IU Health, Indiana University, and Greaves to implement this sampling, he says. “We’re hoping to work with all our community partners to underwrite this program for multiple viruses. Optimistically, it will probably be sometime in September before we can even start with it.”

With monkeypox now being detected in Bloomington’s wastewater by WastewaterSCAN, even more attention will be given to this outbreak. Still, as climate change impacts habitats and international gatherings, and travel makes viruses more accessible, there will be more outbreaks, says McKeen.

“I think that this will take years to control. It took us thousands of years to eradicate smallpox, and here we are, 42 years later, letting another human Orthopoxviral spread amongst us,” he says. “Since the discovery of this particular Orthopoxvirus, it was always limited to areas in central and west Africa. We can’t ignore diseases in poor areas just because they affect Black and brown people. They need to be protected. We keep repeating that mistake.”

Monkeypox is now in 89 countries where it has never been in before, says McKeen. “To me, it is a pretty sad and tragic situation.”