Medical training has long been incorporated into Bloomington Fire Department operations, with emergency medical technicians acting as first responders to medical emergencies. But two years ago, the fire department began recruiting community paramedics to serve in a different role, providing ongoing medical care in its community-based mobile integrated health (MIH) program, also called community paramedicine.

Both community paramedics and emergency medical technicians, or EMTs, are part of the Indiana Emergency Medical Services, a commission within the Indiana Department of Homeland Security. Paramedics differ from EMTs by receiving about 1,200 hours of additional training and completing a certification program. The scope of practice for a paramedic, too, is more extensive, allowing them to address a variety of more complex needs than an EMT can.

While paramedics and EMTs focus on the immediacy of care and triage, a community paramedic takes a more holistic approach to patient care, managing chronic disease or mental health conditions or monitoring maternal health throughout the pregnancy term.

Two years ago, the Bloomington Fire Department began recruiting paramedics to provide ongoing medical care in its MIH program. | Photo by Nick Bauer

As part of a growing nationwide trend to help fill gaps in the healthcare system, MIH works with Monroe County health and social service organizations to provide one-on-one care to patients who use 911 or emergency room services, addressing continuing chronic disease and maternal health.

In the last twenty years, rising health costs, increased emergency room visits, and a focus on health inequities have encouraged more creative thinking, emphasizing a non-emergency approach and increasing efforts to move away from bricks and mortar to meeting people where they live and work. Dr. Eric Yazel, the chief medical director for Indiana EMS, said that MIH is filling that gap.

The Bloomington Fire Department has four community paramedics and anticipates adding three more before the end of the year. In 2023, the program received a $50,000 state grant to fund equipment and technology for medical assessments, advocating for and coordinating holistic care for its 150-plus patients. While it focuses on falls and lift assistance, healthy living, maternal health, substance use, and mental health, the program now assists more people with diabetes, osteoarthritis, cancer, or other chronic conditions, said Shelby VanDerMoere, one of the two original EMTs and who now manages the fire department’s MIH program.

“We are so perfectly fitted for this position,” said VanDerMoere. “We have medical skills, community connections, and public trust. Our program is the perfect way of showing how fire services can adapt.”

Chronic disease management

Chronic disease management is costly and labor-intensive. Educating people about managing their conditions at home and then following up on that care often takes time that physicians no longer have. As a result, the gap widens between what patients have learned from their primary care doctors and their handling of these conditions at home — sometimes exacerbating the chronic conditions to the degree that emergency care or more complicated medical care is necessary.

With ongoing visits by MIH paramedics, chronic conditions can be monitored and patients educated on how to care for themselves.

In 2020, the University of Minnesota studied more than 21 million primary care visits in 2017 and found that primary care doctors spent an average of 18 minutes with each patient.

In a more recent survey by the Physicians Foundation, more than 60 percent of doctors surveyed said they had “little to no time and ability to effectively address” patients’ social determinants of health, such as food availability, healthcare access, financial stability, education, and transportation needs, which they believe have a significant impact on patient health outcomes. Almost 90 percent of doctors who responded to the survey said they would like more time and resources to address these needs in the future.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), people with chronic or mental health conditions make up 90 percent of the nation’s $4.1 trillion annual health expenditures. The most expensive conditions to treat are diabetes ($327 billion in medical costs per year), osteoarthritis ($304 billion), cancer ($240 billion), and heart disease and stroke ($216 billion) — all manageable conditions.

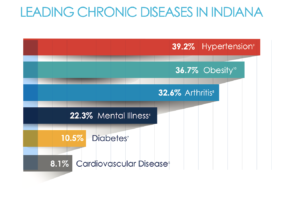

In Indiana, according to the Chronic Care Policy Alliance, the leading chronic diseases are hypertension, obesity, arthritis, mental illness, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Hospital closures

Government and healthcare officials say that finding a way to lessen the economic impact of chronic disease is critical. With MIH services, community paramedics teach their patients how to monitor their chronic diseases, which can, in turn, prevent admission or even readmission to the hospital.

The mobile integrated health program in Monroe County emphasizes a non-emergency approach and increases efforts to meet people where they live and work. | Photo by Nick Bauer

“We are looking at a system with gaps,” said VanDerMoere. “But I think we are the perfect ‘catch-all’ because we are within a 911 service.”

The gaps are more apparent in rural areas, especially. According to a report by the Shep Center at the University of North Carolina, 191 rural hospitals have closed or been converted (they no longer provide in-patient services, although they may provide some health care services) since January 2005. Of these 191 hospital closures, nine hospitals closed from January 2023 to March 2024.

In Indiana, four rural hospitals have closed since 2005. When a rural hospital closes, residents can lose access not just to hospital services but also laboratory tests, imaging studies, and primary care. Often, what remains are fire and emergency services, sometimes shared with other counties.

‘Chronic’ emergency room visits

Providing ongoing, patient-centered care also helps reduce emergency room visits. While many people go to the emergency room for injury-related conditions, most visits tend to be for help with non-urgent needs, according to a Journal of Managed Care study.

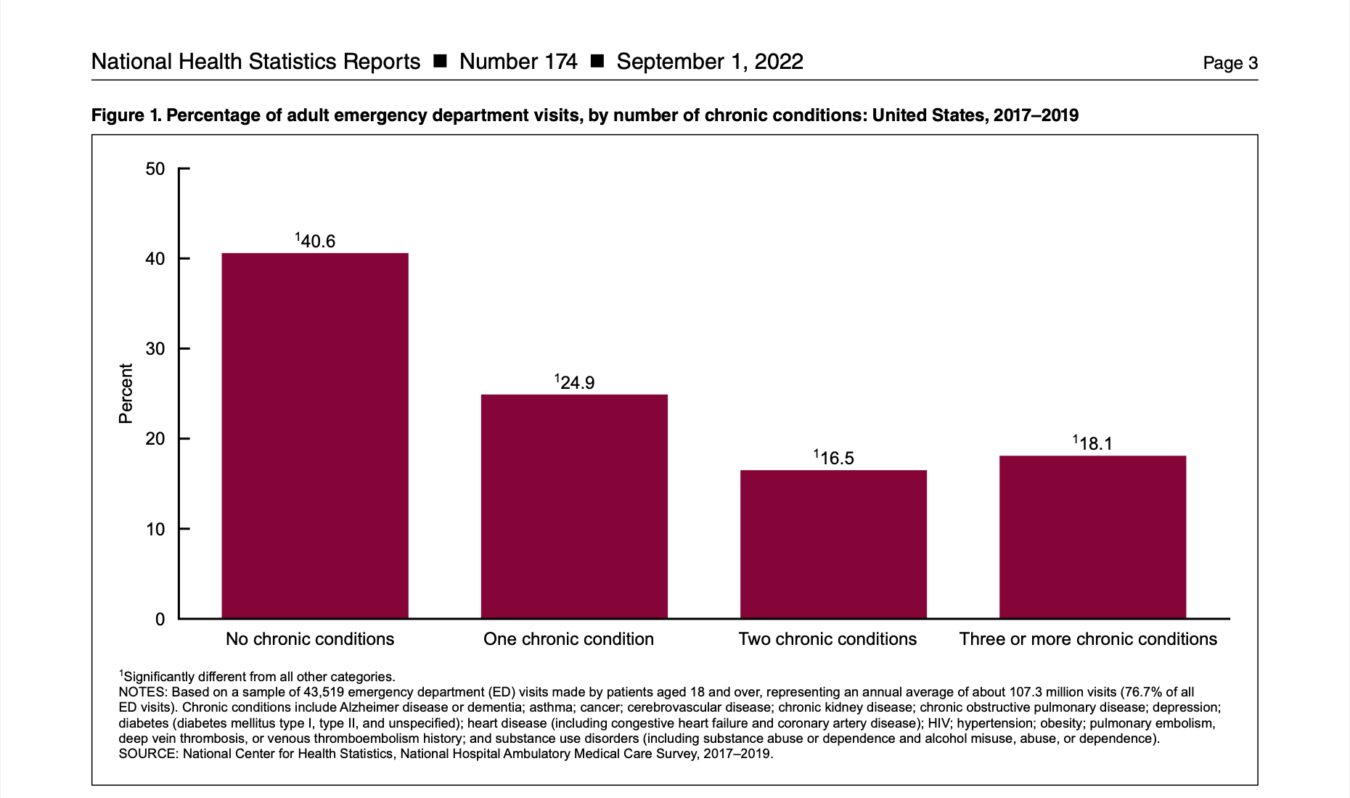

A 2022 report by the CDC found that patients who had at least one chronic condition accounted for 59.5 percent of adult visits to the emergency room, with hypertension and diabetes being the most frequently treated chronic disease in the ER.

In fact, according to the CDC, 140 million people in 2021 went to the emergency room rather than to their primary care physician, with Covid accounting for only 3.8 percent of those visits. For 2022, Indiana had the seventh-highest number of emergency room visits per capita, with 519 per 1,000 residents.

“

People with chronic or mental health conditions make up 90 percent of the nation’s $4.1 trillion annual health expenditures.

”

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Community paramedic Jennifer Knight serves two counties: Greene and Sullivan. Although Daviess County now has an active MIH program, Knight will also see Daviess County patients if they are referred to her. She said that the purpose of MIH is to decrease readmission rates and 911 emergency calls.

“I can go in and see [my patients] and see what’s going on in their home. I can ensure they have appropriate food for their diet, if they have access to insulin, or know how an insulin pump works,” said Knight. “I can fix the problems or help them fix them themselves that will keep them out of having a traumatic experience like spending hours in the ER.”

VanDerMoere agrees, saying the goal is to always prevent hospital and emergency room admissions or readmissions by helping Bloomingtonians manage their chronic disease conditions.

Why is it so important to minimize emergency room visits? For one thing, they are expensive. According to a study by the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, going to the emergency room in 2019 cost about $1,082 per patient, with overall costs between 2012 and 2019 increasing from $54 billion to $88 billion.

In Indiana in 2020, the average cost of an emergency room visit was $1,618, or the 25th most expensive state in the country.

But does MIH save money? One Canadian study examined whether MIH delivered by all emergency medical services, or EMS, was more efficient than regular ambulance services in addressing urgent care needs in the community. The study found that compared with ambulance response, the MIH team spent 10 to 15 minutes more with the patient but reduced by 45 to 50 percent the number of patients transported to the ER.

Starting MIH in Indiana

In Indiana, legislation passed in 2019 created a $100,000 grant funding program, overseen by Indiana EMS, to help local EMS providers pay for the cost of starting an MIH program. Initially, six counties applied for this funding.

Subsequent legislation allowed for a broader range of funding resources for preventive care during emergency runs. More than half of Indiana counties now have a mobile integrated healthcare program, for a total of 113 programs statewide.

Indiana had the seventh-highest number of emergency room visits per capita in 2022, according to KFF Health News.

Indiana law allowed for the creation of an advisory committee to oversee the approval and implementation of MIH programs throughout the state. The committee provides feedback to the EMS commission but has not yet created separate state program standards and licensing requirements.

According to the National Academy for State Health Policy, the attitude in Indiana is that MIH programs respond to local community health needs and, therefore, must be managed locally. As a result, MIH programs and their services vary from county to county and depend on healthcare services and resources existing in those counties.

In southern Indiana, only eight counties have viable programs: Monroe, Greene, Sullivan, Daviess, Knox, Posey, Vanderburgh, and Clark, largely because of the limited EMS services available in other areas.

According to Yazel, southern Indiana is more rural, so the demographics and logistics of providing care are more complex. Patients are farther apart. Resources are tighter. Workforce issues impact the ability to provide MIH care.

Dr. Eric Yazel, chief medical director for Indiana EMS. | Courtesy photo

“When you get in some rural areas, and it’s 15 miles between appointments, logistically, it’s challenging,” said Yazel. As a result, he added, “traditionally, there hasn’t been as much EMS investment at the public level in the southern part of Indiana. I would like to see, especially in our rural areas, MIH programs in essentially every county, at least, to have the capability to have coverage there by the end of 2024.”

Acquiring funds for such programs, however, has been challenging. Ambulance services around the country originally were created to transport patients to hospitals, with little to no treatment onsite. Although emergency medical workers in recent decades have been trained to provide more sophisticated care, most bill for their costs only if they transport a patient to the hospital.

A few states, like Maryland and Minnesota, have been working on MIH reimbursement models, said Yazel. In Indiana, efforts are in the early stages to create a more stable reimbursement model.

In 2020, the Indiana General Assembly passed HB 1209 that became a law allowing the state Medicaid agency to reimburse EMS providers for emergency services in the home as long as the services are provided in response to a 911 call. In the past, reimbursement typically came from state and federal grant funding that supported MIH programs.

Reliance on grant funding to sustain existing programs is a problem, said Yazel, because “at the end of the day, being grant funded, you are kind of living paycheck to paycheck, and it limits your long-term planning.”

But in 2023, the Indiana General Assembly changed this equation with a $15 million allocation over two years for emergency medical services.

“We kinda rode the coattails of our public health funding,” said Yazel. This is the first pot of money designated strictly for EMS, including funding for mobile integrated health, he said. “Our end goal is sustainability. I think we are at the stage where we’ve demonstrated our worth to the system.”

MIH pioneer Project Swaddle

Across Indiana, MIH programs vary in whom they serve and the services they provide. One of the first MIH pioneers was the Crawfordsville Fire Department in Montgomery County. Headed by EMS Division Chief Paul Miller in 2013, the department began conversations about MIH by meeting with the local hospital, government officials, and the Indiana Department of Health. Miller said that he wasn’t allowed to use any tax dollars to implement the project.

Now, the program relies on funding through Franciscan Health and various grants. The partnership has essentially driven the program from its beginning.

First, the Crawfordsville MIH team tackled cardiac care, but their next program, Project Swaddle, which provides prenatal and postpartum care for mothers, got national and statewide attention.

First, the Crawfordsville MIH team tackled cardiac care, but their next program, Project Swaddle, which provides prenatal and postpartum care for mothers, got national and statewide attention.

Miller said Project Swaddle was particularly effective for stays in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and for unplanned readmissions that happen within 30 days of discharge after cases of heart failure. “We’ve had hugely successful outcomes in reducing NICU stays, so each time a baby stays in a NICU, it’s about $175,000 a week just for that care,” he said. “For our heart failure project, we saw zero 30-day readmissions for anyone enrolled in that project for the last two years.”

The success of the Crawfordsville program has encouraged other MIH programs statewide.

Registered nurse Courtney Dyer (left) and paramedic Nick Green started Project Sprout in the Monticello, Indiana, fire department’s expanded MIH program. | Courtesy photo

The city of Monticello and the Monticello Fire Department expanded its MIH program to include maternity services in 2022. Courtney Dyer, a registered nurse specializing in maternal, infant, and child care, joined the program and started Project Sprout with fire department paramedic Nick Green, who focuses on chronic disease management. Project Sprout works with mothers until four months postpartum.

One of the elements of Project Sprout is the Count the Kicks program. This pregnancy app teaches mothers-to-be how to count how active their babies are in utero. “It tracks a baby’s typical movement,” said Dyer. “It helps to save babies by teaching mothers to notice when their babies might be in distress.”

Once Dyer and Green receive a patient referral, they may meet the patient at the hospital before discharge or at home. Then they follow them for at least thirty days to assess the patient’s needs. “What mobile integrated health does,” said Green, “is fill the proactive gap [for providing health care].”

“We want to know the social detriments of health that we’re addressing. What is the patient going to eat? How will they get to their appointments?” said Green. “At the root of it, you’re helping people manage their [healthcare] resources. And it’s working. Monticello MIH has shown a 7 to 8 percent reduction in hospital readmissions.”

Community paramedicine

In Posey County, one full-time paramedic who covers the entire county addresses chronic health conditions. Paul Micheletti, director of operations for Posey County EMS, and his MIH team designed their MIH program to “remove a subset of chronically ill patients from the 911 system to community paramedic services.”

The program provides weekly appointments at patients’ homes for healthcare assessments, medication reconciliation, and patient education on their needed care. “This program returns the ‘house call’ to county residents and allows them to stay at home rather than placing the burden on the healthcare system,” said Micheletti.

“

I can go in and see my patients and see what’s going on in their home. … I can fix the problems or help them fix them themselves that will keep them out of having a traumatic experience like spending hours in the ER.

”

—Jennifer Knight, Greene County paramedic

To help other MIH programs, the Indiana Rural Health Care Association has created a community paramedicine program and has worked with partners at Monticello Fire Department in White County, Good Samaritan Hospital in Knox County, and Franciscan Health in LaPorte County. In White and LaPorte counties, the community paramedicine programs started as maternal- and child-health programs. In White County, they’ve expanded their program to include chronic disease management and hospital readmission prevention.

Bottom line priorities

To grow, MIH must ensure it has a trained workforce and program reimbursement necessary to succeed, the two biggest obstacles it currently faces.

According to the 2022 Indiana EMS Workforce Shortage survey, states nationwide face increasing shortages of paramedics and EMTs. In Indiana, from 2018 to 2022, the number of EMS calls increased by 60 percent, while the number of EMS personnel decreased by more than 4 percent.

The survey found that Indiana had 4,587 paramedics in 2022, with EMS call volume increasing by 34 percent between 2019 and 2022. While EMTs and paramedics may work together, in Indiana, paramedics require 452 hours of training and an internship course of 1,000 to 1,300 hours. An EMT requires only 50.5 hours of training. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average annual wage for all EMS workers in Indiana is $35,350, which is slightly higher than in most neighboring states: Illinois ($43,310), Kentucky ($31,250), Michigan ($33,760), and Ohio ($34,020).

“Right now, we have 4,700 licensed paramedics in the State of Indiana, and at last check, only 1,600 of them had filed an ambulance run in the past calendar year,” said Yazel. “That is not even enough to cover the greater Indianapolis area, let alone the whole state.”

“We are so perfectly fitted for this position. We have medical skills, community connections, and public trust. Our program is the perfect way of showing how fire services can adapt.” —Shelby VanDerMoere, manager of Bloomington Fire Department’s MIH program

Indiana is not alone. Nationwide, counties, and towns are experiencing a shortage of EMTs and paramedics. A 2022 survey by the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians found that, since 2019, applications for paramedic and EMT positions were down an average of 13 percent, with a 65 percent decrease in applications.

One key advantage of the MIH staffing program is that it offers 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. work hours in healthcare delivery, said Yazel, so he’s hoping to pull in some EMS providers who would prefer a more routine schedule for their lives.

Of the $15 million recently allocated by the state for emergency medical services, $5.7 million is designated as an investment for workforce assistance and education grants. Mobile integrated healthcare is eligible for those funds, although there is no standard training program for MIH community paramedics in Indiana. “There are a lot of variances there,” said Yazel. “It’s still kind of the Wild West out there.”

A recent Ohio State University College of Medicine study examined the training of MIH clinicians. It found their certification levels varied from state to state and that nearly half of the clinicians received less than 50 hours of MIH training. Only a third received more than 100 hours of training.

The healthcare community still struggles with where and how MIH fits within the healthcare continuum. A contributing factor is the lack of overall standardization in the program, which creates an uncertain perception of it. According to Yazel, hospitals are still hesitant to work with MIH programs, often seeing the program as a “community service program” rather than a program critical to the bottom line.

Addressing mental health with MIH

Although progress was made on MIH reimbursement with the passage of HB 1209, payments are still limited. Only those programs that Indiana’s EMS commission approved receive reimbursement.

Still, full Medicaid reimbursement is under debate, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy. Numerous state MIH programs are working to navigate Medicare and Medicaid for reimbursement of services, said Victoria Reinhartz, board member of the National Association of Mobile Integrated Healthcare Providers. “Every day, we hear about another program that has successfully been able to navigate and get established as a provider from the standpoint of being able to submit billing codes and get paid through Medicare and Medicaid,” she said.

Mobile integrated healthcare teams can also apply for a Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration waiver in support of MIH services for severe mental illnesses or for federal funding through the American Rescue Plan Act’s Section 9813, which outlines the option for a state to seek an enhanced national Medicaid match for mobile crisis intervention services. Overall, Indiana has not fully committed to funding MIH programs across the state, and MIH teams still depend on city, state, and federal grants to support these programs.

“

The MIH program returns the ‘house call’ to county residents and allows them to stay at home rather than placing the burden on the healthcare system.

”

—Paul Micheletti, director of operations for Posey County EMS

In the 2024 legislative session, the Indiana General Assembly added a mental health component to the MIH program under SB 10 by creating the Community Cares Initiative Grant Pilot program, which would address mental health under the MIH program. In the Indiana House, SB 10 language was incorporated into HB 1385. That bill was signed by Gov. Eric Holcomb in March.

Also in the session, SB 142 introduced funding for a pilot program requiring insurer reimbursement for MIH services, but it stalled in the House. “We aren’t taking it as a total loss though, because I believe one of the main issues was it wasn’t considered expansive enough,” said Yazel “So [we are] hoping that it can springboard into something with a wider reach next session.”

The pilot program is based on a Noblesville Fire Department program, NobleACT, which addresses crisis mental health through MIH.

“I don’t think at the end of 2024 it is probably feasible to have that [full] reimbursement model in place,” said Yazel. “But I think some of our third-party payers [Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance] are getting more involved in pilot programs, so I would like to see that expand.” Yazel said he believes that MIH programs are halfway to sustainability through Indiana’s Medicaid agency.

However, the long-term sustainability still depends on the success and metrics of the programs across the state. Yazel acknowledges that numerous subcommittees within the Indiana EMS commission are considering pressing workforce, training, and reimbursement issues.

In the long run, Yazel said, MIH is a system where everybody wins. “You’re giving services to your most vulnerable. You’re saving money for the healthcare system,” he said. “You’re filtering out less acute EMS runs so [EMS] can respond to 911 calls. MIH delivers nimble, low-cost services to its patients in their residences. It focuses on providing services for those most vulnerable in a community that may struggle to navigate the traditional [healthcare] system.”

This article was made possible by underwriting support from the Bloomington Health Foundation. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs, including mental health, in Bloomington and neighboring communities.

This article was made possible by underwriting support from the Bloomington Health Foundation. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs, including mental health, in Bloomington and neighboring communities.