“Matt Hart’s FAMILIAR is a wrestling match that morphs into a bear hug. & I mean that. This book’s a dapper flaneur stroll across time & space & the twisty landscapes of punk rock. Come on. Let’s listen to Matt Hart pronounce secret truths through the spinning wah wah blades of Whitman’s epic pedestal fan. Is this translation? Is this the grass? Part scorch, part drone, part weeping riff, this wrenching poem alchemizes new music from syllables you thought you knew. Read this book & stay stay stay stay stay ‘steady / tender / connected’.”

—Kiki Petrosino, author of Bright: A Memoir and White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia

Matt Hart is the author of ten poetry books. His poems, reviews, and essays have appeared, or are forthcoming, in print and online journals that include American Poetry Review, Big Bell, Conduit, jubilat, Kenyon Review, Lungfull! and POETRY. He has been awarded a Pushcart Prize, a grant from The Shifting Foundation, and fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and the Warren Wilson College MFA Program for Writers. From 1993 through 2019, Hart was a co-founder and editor-in-chief of Forklift, Ohio: A Journal of Poetry, Cooking & Light Industrial Safety. He lives in Cincinnati where he teaches at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, co-edits the (sometimes) journal Sôrdəd, and plays in the band NEVERNEW.

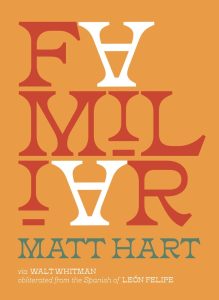

Hart’s latest book, FAMILIAR (Pickpocket Books, 2022), offers gritty glimpses of ghosts and personal epiphanies that ironize Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (1855). While Hart’s long lines, accumulating images, and catalog of perceptions recall Whitman’s poem, FAMILIAR is remarkable for unpredictable octaves and unique registers that enable it to read like a spoken word script, yearning to be sung. As Hart wrote, “I will sing to you and you can sing to me.”

Despite comparisons of FAMILIAR with “Song of Myself,” Hart says that the two poems are “wildly different” from each other. He calls his poem “a new work that enacts/evokes some resemblances” to Whitman’s poem, his original source material, “especially formally and structurally.” Yet, he says, “The content is all new. 1855 was a long time ago. FAMILIAR is a poem for right now.”

O/bliterated

“FAMILIAR” is Hart’s tenth poetry book.

Through reconceived processes of “obliteration” and “translation,” Hart attempts to remove his poem from its original source as much as he can. At the same time, he embeds himself and his personal experiences within his reconstructed source material to produce his new content.

Hart describes “obliteration” as “a temporary and loving erasure,” or a process of reconstruction that leaves the original text undestroyed. Unlike destruction, obliteration uses translation to “discover something new via the wreckage that occurs when one dismantles and disarms another text to radiate, rather than delineate, meaning and to discover as yet unknown territory hidden inside it.”

Hart explains: “Whitman’s poem remains intact,” although Hart had “obliterated” it “across the mitigating force of León Felipe’s Spanish translation” of Whitman’s poem.

“Obliteration begins with literal translation,” Hart says. And “translation,” for him, is the process of recreating something. By “recreation,” he also means, “a way to play, to experiment, to discover, to excavate.” Through “association, juxtaposition, fragmentation, homophonic, antonymic, and synonymic substitution,” obliteration creates something new “that echoes, and corresponds with the original.” For example, through obliteration and translation, the opening line of “Song of Myself” — “I celebrate myself, and sing myself” — became “O/bliterated singer, I obliterate y/ourself,” the first line of FAMILIAR.

Hart says, “There’s a sense in which everything ever written is a translation, because words are not their referents,” calling translation “the most abstract of reductions.” And because the “original is already right,” he says he needs to make many “mistakes” to produce something new while interacting with the original untranslated text. That is why he is “much more interested in error” than in “parroting something to get it right.”

More on obliteration, translation, and the writing process behind FAMILIAR can be found in “Beforehand,” the book’s introductory section.

Language made noisy with god

The title of Hart’s book derives from his unique perception of the “familiar.” He says his book’s titled sections are “familiars,” or “friends, companions, correspondents, heroes and heroines.” The titled “familiar” sections have epigraphs, shorter lines, and no end punctuation, and “flow in a somewhat contrary way to their long-limbed friends,” Hart says. Examples of section titles are “(Ghost),” “Prophecy,” “Chain Letter,” “Where the Screams Come From,” and “Wake Up! Wake Up!”

By contrast, the book’s numbered sections more closely resemble “Song of Myself,” due to their long lines and heavy punctuation. Even so, Hart says Whitman’s poem is also “familiar” to him like a friend or a companion.

“If one has a process, there is no such thing as writer’s block.”

—Matt Hart

To write his titled “familiar” sections, Hart began by handwriting a three-page poem with a Jack Spicer epigraph reading: “Poems should echo and re-echo against each other. They should create resonances. They cannot live alone any more than we can.” Dissatisfied with his first draft, Hart put it aside and rewrote it from memory. For a year, he continued this process of rewriting first drafts from memory, and observed that his two drafts were “talking to each other animatedly and also disagreeing vehemently.” Hart says, “It was like playing a game of ‘telephone’ with myself.” Such lively textual engagements recall Hart’s definition of poetry as “language made noisy with god.”

The writing process

Thinking he would learn to pen “better” song lyrics, Hart started writing poetry in college, where he majored in philosophy. While that writing experience did not lead to the kind of lyrics he had wanted, it changed his life, and made him attentive to language “in a whole new way.”

Having been a musician who played in bands before he became a poet, Hart sees poetry and music as “entirely different animals.” For him, the experience of writing song lyrics is completely different from that of writing poetry. “A poem is the words and the music in the very same breath,” he says, while “lyrics are just one element of a song” that he produces only after he composes the song’s music.

“Poems should echo and re-echo against each other,” Hart says. “They should create resonances. They cannot live alone any more than we can.”

Hart was first drawn to poetry writing due to its “singularity” and “solitary-ness.” He also found appealing “the fact that an overflow of powerful emotion might, in fact, be produced via words alone.” He says, “Writing poetry is a matter of activating an atmosphere — of associations, sounds, etymology, juxtapositions, connotations, allusions, references — and charging it with the electrical current of the process. Poetry can be louder than the loudest rock band and as quiet as the whisper of a small mouse against your eardrum.”

Although Hart was drawn to the solitary aspect of writing poetry, he finds that through obliteration, he engages with multiple authors, texts, and the subjects embedded within them, as though he were playing in a band. In FAMILIAR, these authors are Whitman and León Felipe, with what he calls “guest appearances” through the poem’s epigraphs by Sonic Youth, Mission of Burma, Jack Spicer, The Hold Steady, William Carlos Williams, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, among others. His wife, Melanie, and his daughter, Agnes, also make guest appearances.

“It is a music and poetry festival, and I get to jam with the most inspiring sources in my life,” Hart says.

Hart calls himself a “very process-oriented poet,” who writes every day. In his basement office, he begins his day by reading and listening to music before he writes, alternating between typewriter, pen and paper, and computer. He says that instead of beginning with an idea, he puts words down on a page and tries to “follow them where they want to go.” Yet, he believes in process. “If one has a process, there is no such thing as writer’s block,” he says.

Hart shares two other strategies, besides having a “sustainable process,” for overcoming writer’s block. He says not to worry if “what you write is any good” and that “one writes because the process itself is a blast and because one loves playing with the language.” He also says he is “a-okay” if what he writes on a daily basis “doesn’t amount to anything” because “quantity leads to quality eventually.”

‘Inspiriting’

Revision is a constant aspect of Hart’s writing process. For him, a poem is “a site of possibility and instability” that invites continuous revision. He says, “I will probably change things in FAMILIAR when/if Pickpocket does a second printing, because I can’t stop thinking about what might happen if…” Such changes could lead to a “better” or “worse” version of his poem.

“I don’t think poems need to be fixed,” Hart says, “and in fact I like to make sure in every poem I write there’s also something a little bit off — that thing that I can’t quite be comfortable about.” That is why he believes workshops should be “entirely descriptive.” Such workshops would help writers understand their own writing choices instead of asking them to adopt “certain expectations that the work is refusing to satisfy.”

“Send the stuff you’re excited about,” Hart advises writers. “Everything good that’s ever happened to me as a writer has happened via connections and friendships I’ve made with people in the poetry community.” He recommends going to open mics, starting a literary journal or a reading series, joining writing groups, and attending writers’ conferences.

But “most importantly,” he says, “be genuinely interested in other people and what they’re doing and attempt to help them in whatever ways you can. Kindness and generosity are everything. It’s not hard to get published. It’s hard sometimes to make room for other people in your life.”

Hart’s favorite line from FAMILIAR concludes the poem’s second section:

And your spirit thus inspirited will echo through the

universe, exactly like my spirit, yet totally

different.

He says, “What’s inspiriting the spirit here is a proposed engagement with a process of discovery and communion through art and art-making.”

FAMILIAR celebrates similarities and differences among people. Hart says, “Our similarities connect us, but our differences enlarge the world and, through the imagination, activate empathy.” Although the imagination is “not perfect,” together with “qualities like kindness and generosity and a willingness to listen we can at least attempt to find our feet with each other — and potentially LOVE radically and more,” he says.

Hart says there is nothing he would change about himself, or his life, right now. “I’m so grateful for the time that I have on this earth to be alive.”

Pickpocket Books and Ledge Mule Press

FAMILIAR is published by Pickpocket Books, an imprint of Bloomington publisher Ledge Mule Press, which was founded by Dave Torneo and Ross Gay and residing in the historic I Fell building at the corner of East 4th & South Rogers streets in Bloomington.

FAMILIAR is published by Pickpocket Books, an imprint of Bloomington publisher Ledge Mule Press, which was founded by Dave Torneo and Ross Gay and residing in the historic I Fell building at the corner of East 4th & South Rogers streets in Bloomington.

Ledge Mule Press

415 W. 4th St.

Bloomington, IN 47404

Contact them at [email protected]

Matt Hart’s other poetry books can be purchased on his Amazon.com author page.