Lois Sauder learned that she had Alzheimer’s disease when she was in her 50s. She is now 72 years old. Lois is a petite, shy woman with a soft smile and kind nature. She can still dress herself. She can cook simple recipes and sew simple embroidery designs. She can listen to audiobooks. She can take a walk on her property in Bloomington where she lives with James, her husband of 50 years, and her son and daughter-in-law, who live next door.

But as her disease advances, she finds that she can no longer grocery shop. Big crowds, even big family functions, bother her. If she’s cooking, she can never leave the kitchen or she may forget that she’s cooking. Right now, at this stage in her disease, she is mobile, happy, and coping beyond what she expected. She’s been fortunate to be in a clinical trial and is currently on medication.

For those like Sauder, a diagnosis of early onset Alzheimer’s means she can have many good years ahead. Her life will change, and there will be things that she cannot do. But today, more and more people are living with Alzheimer’s because they are getting diagnosed earlier.

Are we prepared?

The Alzheimer’s Association’s report “2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures” addresses prevalence, mortality and morbidity, caregiving, the dementia care workforce, and the use and costs of health care, long-term care and hospice.

Right now, more than 6.5 million Americans age 65 and older are living with Alzheimer’s, and despite millions of dollars invested on research into Alzheimer’s, it is still a progressive disease with no cure. The 2022 projections of the Alzheimer’s Association show that the disease will affect 27 percent of those 65 to 74 years old, 37 percent of those 75 to 84, and 36 percent of those 85 and older. In Indiana, projected numbers for Hoosiers 65 and older for 2020 were 110,000, but by 2025 it will be 130,000. According to information collected by the Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center (ADRC) at Indiana University Health, 5,467 people have Alzheimer’s disease in the nine south-central Indiana counties of Washington, Owen, Morgan, Monroe, Martin, Jackson, Greene, Daviess, and Brown.

“These figures are based on those 65 and older, so the numbers are likely higher,” says Dayna Thompson, ADRC’s executive director.

But these numbers are expected to surge. According a 2022 report by the Alzheimer’s Association, barring medical breakthroughs, 13.8 million Americans will have Alzheimer’s in 2050.

What’s driving these numbers? The 2020 U.S. Census projects that by 2030 all baby boomers — people born between 1946 and 1964 — will be at least 65 or older, or 21 percent of the U.S. population. With an influx of people 65 and older, communities, healthcare organizations, and the government will need to address the impact of this disease even more, simply because the population will be grayer. Ironically, the incidence rate for Alzheimer’s disease has decreased in the past 25 years, due to better health, increased education, exercise, and other factors.

Alzheimer’s disease falls under the classification of dementia, a disease for which there are many conditions. Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia. Because many people think of Alzheimer’s as an “old person’s disease,” it is often under-diagnosed. Alzheimer’s affects a person’s memory, language, thinking, and cognitive abilities. As a person ages, the disease kills the brain’s neurons and brain tissue. A person with this disease gradually forgets simple functions, such as how to brush their teeth, use a spoon, get out of bed, or even recognize themselves in the mirror.

Even with all the sophistication of science and technology today, researchers haven’t found a cure for Alzheimer’s, although research is booming. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, the total cost of Alzheimer’s and dementia care for 2022 is estimated to be $321 billion, with Medicare paying $146 billion and Medicaid paying $60 billion for those Americans 65 and older. These costs emphasize the continued importance of research toward finding a cure for the disease.

For fiscal year 2024, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget includes additional funding of $321 million for new research with the overall resources needed in the amount of $3.9 billion.

Dayna Thompson, executive director of Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center at Indiana University Health. | Courtesy photo

Whether the U.S. has the resources to care for this onslaught of gray remains debatable, due to the lack of geriatricians, neurologists, and trained primary care physicians. Not only do we need to prepare our future generations of healthcare providers, but we also need more of them, says Thompson.

“There are some clinicians that get it and are knowledgeable and well equipped to work with these patients, but I don’t think we have enough of those people,” says Thompson. “I do not think [providers] are prepared.”

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, more than 46,000 geriatricians will be needed in 2050 to care for the population over 65 years old needing geriatrician care. As of 2021, the number was 5,170. Right now, Indiana has only 87 board-certified geriatricians for the entire state. Bloomington has zero board-certified geriatricians, says Thompson. According to the American Board of Physician Specialties, a board-certified geriatrician will have completed medical school including “a residency in a program approved by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education or the American Osteopathic Association and deemed acceptable to the Board of Certification in Geriatric Medicine.” They must be qualified in internal medicine or family practice.

In many cases, the primary care physician is the starting point for those with early onset Alzheimer’s. Though the U.S. has more primary care physicians than geriatricians, it is still not enough, with 50 percent of all primary care physicians saying they are unprepared to care for a patient with Alzheimer’s. Plus, dementia neurology deserts exist in 20 states, meaning fewer than ten neurologists per 10,000 people with dementia will exist in 2025.

Since the pandemic, the U.S. also has had a persistent shortage of specialists, certified nursing assistants for skilled nursing facilities, and nurse practitioners. We need more nurses, more geriatricians, nurses’ aides, and personal care workers, says Dr. Kathleen Unroe, IU School of Medicine, and we need to train them for a wide range of behaviors, to work with patients at all stages of their disease. The Alzheimer’s Association projects that by 2028, more than 4 million home health and personal-care aides will be needed in the U.S. As of 2018, only 3 million were working as aides.

Years of research wasted

Even today, though, the science of Alzheimer’s is uncertain. For years, scientists focused on two theories. The original theory, identified by German psychiatrist and neuropathologist Alois Alzheimer in 1906, was grounded in the idea that amyloid protein formed plaques that strangled healthy brain cells. This became the leading theory of Alzheimer’s disease.

In the 1980s, the main protein in the plaques was discovered to be beta-amyloid that had a tendency to clump together in the brain. Beta-amyloid became the leading theory for the cause of Alzheimer’s disease.

The second focus arose in the 1990s, when scientists believed that the degeneration of another brain protein, tau, was more directly linked to Alzheimer’s disease than beta-amyloid. Tau was known to hold cell doors open to receive nutrients, and when they began to clump together those doors would close, starving the brain cells.

Despite continued research on these theories, all have failed to discern the real reason someone gets Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, in these thirty years of research, no one has been able to explain why some people with these plaques did not have Alzheimer’s disease. These discoveries made post-mortem are now more easily discovered in less invasive imaging tests like PET (positron emission tomography) scans.

But a recent investigation of a 2006 study called into question the beta-amyloid theory when researchers discovered that the study contained altered or duplicated images.

In a 2006 paper published in the journal Nature, researchers from the University of Minnesota had purified an Aβ*56 protein from the brains of genetically modified mice and injected it into rats’ brains. They found that this protein caused the rats to develop symptoms like those in humans with Alzheimer’s, confirming the beta-amyloid hypothesis for many researchers.

However, in August 2021, Matthew Schrag, a neuroscientist and physician from Vanderbilt University, discovered the altered images and reported them to Science magazine. After a six-month investigation, Science announced on July 21 that the review supported Schrag’s suspicions and raised questions about the 2006 study.

Science and Nature magazines and the University of Minnesota Medical School are reviewing these issues, but not before the study had been cited in scientific papers more than 2,300 times and was the precedent for much Alzheimer’s research over the past sixteen years. As a result, research on beta-amyloid plaques has yielded no discernible cure or successful pharmacological intervention for Alzheimer’s.

A person with this disease gradually forgets simple functions, such as how to brush their teeth, use a spoon, get out of bed, or even recognize themselves in the mirror.

Alzheimer’s research is now taking a multitude of directions, some examining the gut biome, immune system, inflammation, genetic aspects of Alzheimer’s, the impact of toxic proteins, and lifestyle and behavioral interventions. The National Institutes of Health recently funded an early-onset Alzheimer’s study and new treatments at the IU School of Medicine with $16.6 million.

IU has received funding for Alzheimer’s from the NIH for the past six years and recently received an additional $50 million grant from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). According to an article by WFIU, this grant will continue the work on the Model Organism Development and Evaluation for Late-Onset Alzheimer’s disease, a framework of research established by NIA in 2016. Despite this funneling of research cash, the search for a cure has never been more urgent.

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease

When Bloomington resident, Steve Taylor was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, he was 65. While still a banker at JP Morgan Chase, he found that he forgot banking rules, regulations, and procedures while working, making mistakes, and often forgetting that he’d made them. Taylor knew something was wrong. His bosses knew something was wrong. So he retired and began a series of neurological and cognitive tests to determine what was wrong.

The doctor, Taylor says, was impressed with his verbal abilities, something Taylor had always prided himself on. But after testing, he and his wife, Susan, were told that he had early onset Alzheimer’s disease. The National Institute on Aging defines early onset Alzheimer’s disease as occurring in someone under age 65.

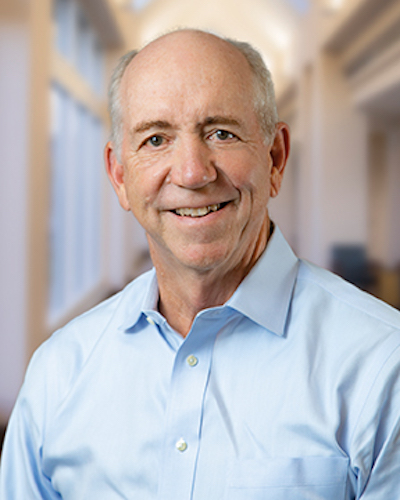

Dr. Patrick Healey of the Center for Healthy Aging at Ascension St. Vincent in Indianapolis. | Courtesy photo

Sometimes, according to Dr. Patrick Healey of the Center for Healthy Aging at Ascension St. Vincent in Indianapolis, an early onset diagnosis is challenging to make. It’s tricky, says Healey, when a person has developed greater skill sets, because the diagnosis might not be as obvious. For people with high levels of education or who are gifted intellectually, says Healey, it’s easy to attribute some changes to the typical aging process.

Healey says 80 percent of the diagnostic process depends entirely on interviews with the patient and their family. He talks to family members and the patient to find out what behaviors a person has been exhibiting — what they have and haven’t been able to do. “Basically, what I tell families is that I’m hopping on the journey with you,” says Healey, who has been a certified geriatrician since the 1990s.

Alzheimer’s behaviors can be disturbing to family and friends. When a loved one exhibits behaviors that are not typical for that person, family members can become shocked, not knowing where to turn.

“How do we inform the families that this disgusting behavior is not their fault and that their loved one is not a dirty old man?” says Healey.

Unlike other diseases, like heart disease or cancer, Alzheimer’s does not manifest the same for everyone. “One of the problems with Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia in general, is that we don’t have a [real] biomarker for the disease,” says Healey.

A biomarker is a “measurable indicator of what’s happening in the body.” For instance, increased cholesterol in a person’s blood is a biomarker for heart disease, or increased sugar in the blood is a biomarker for diabetes.

“We have scans that help make the diagnosis but are not fully verified as true biomarkers, meaning a positive scan is not enough to diagnose Alzheimer’s every time accurately,” says Healey. “In highly specialized research centers for Alzheimer’s disease, researchers have used the combination of beta-amyloid on the PET scan and blood or CSF [cerebrospinal fluid] biomarkers to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease.”

According to Dementia Care Central, there is no single blood test for Alzheimer’s that has received full FDA approval, although multiple tests are in development. “As a result, these new tests have not been available in the usual clinical setting,” says Healey. “Additionally, the new blood biomarkers should be used only in specialized memory units until we have more data on real-world patients.”

Four blood tests have received the FDA’s “breakthrough device” status: Preclivity by C2N Diagnostics, Quest AD Detect by Quest Diagnostics, Diadem’s AlzoSure Predict, and Simoa.

“How do we inform the families that this disgusting behavior is not their fault and that their loved one is not a dirty old man?” —Dr. Patrick Healey of the Center for Healthy Aging at Ascension St. Vincent in Indianapolis

Before, brain tissue was studied only post-mortem, though now, with improved technology, doctors use expensive imaging like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomography (CT), and PET scans to help diagnose dementia. A PET scan identifies amounts of beta-amyloid plaque, tau proteins, and fluorodeoxyglucose in the brain. They can even gather information from a cerebrospinal fluid test, which examines brain cell proteins in the spinal fluid.

Many researchers still believe that the beta-amyloid is the predominant hypothesis, despite the results of the 2006 study now being questioned. But it just may not be the right form of amyloid, or researchers are starting too late in the disease progression, wrote Derek Lowe in his article, “Faked Beta-Amyloid Data, What Does It Mean,” published in July in Science.

While imaging is becoming more thorough, the most critical evaluations are cognitive assessments like the GPCOG or Mini-Cog tests for cognitive impairment.

Living with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis

When Steve and Susan Taylor received Steve’s diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, it was a massive shock, a feeling like “I was having cold water dumped on our heads,” says Steve.

It was the same for Robert Hershberger, author of The Diary of an Alzheimer’s Caregiver. His wife, Dee, was diagnosed in 2015 with Alzheimer’s at age 76. “When she first had memory issues, I didn’t think it was Alzheimer’s,” says Hershberger.

Hershberger and Dee first saw a psychologist, then a doctor, and then ventured to the Mayo Clinic, where she underwent various tests. “I was just devastated,” says Hershberger. “I just fell apart. She was so steady and optimistic. She said several times that she is going to beat this.”

Living with the stigma of the disease is difficult too. For 72-year-old Lois Sauder, she knew deep down that something wasn’t right; she just wasn’t ready to admit it. “But I’ve decided I just had to make the best of it,” she says. It helps to have contact with others who share the same challenges. But even her family has struggled with the diagnosis. Since Sauder is early onset, she doesn’t appear to have what most people think is Alzheimer’s.

“A lot of people think that people with Alzheimer’s or dementia, you just sit there and can’t do anything,” says Sauder. “The majority of my husband’s family think that I don’t actually have Alzheimer’s because of how they see the stigma of disease itself. That’s their meaning of Alzheimer’s.”

Depending on what stage a loved one is in, being a caregiver is a demanding, 24-hours-a-day job. Robert Hershberger and Susan Taylor were their spouses’ primary caregivers. Hershberger tried caregivers from outside his house, but his wife didn’t like to have them in her home.

Robert Hershberger details his wife’s struggle with Alzheimer’s disease in his book The Diary of an Alzheimer’s Caregiver (Purdue University Press, 2022).

“She threw one of the gals out,” he says. “She just opened the door and pushed her out.” He finally found himself depending on family friends and church friends to help.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, 83 percent of all caregivers are family members, friends, and other unpaid caregivers. In 2021, caregivers provided an estimated 16 billion hours of unpaid assistance, valued at $272 billion, 70 percent of which family members provided.

Caregivers, primarily women, are often adamant about keeping their family member home, either out of obligation or to be closer to them. But it can be an expensive and lengthy process. Caregivers, too, can experience extreme stress, depression, isolation, financial pressure, or even personal health problems due to the care.

Since Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease, an early diagnosis may mean that a loved one needs less care, an estimated 151 hours per month. But as the disease progresses, because of increased needs and attention, caregivers may expend 283 hours per month.

A caregiver’s time also increases depending on their loved one’s condition. If they can no longer dress, go the bathroom alone, or feed themselves, they take more caregiving time. If a loved one is combative and aggressive, not only do they need more help but they can also be a danger to themselves and others. Hershberger’s wife had many episodes of combativeness and aggression.

“The minute that I turned my back on her, I would get cold-cocked on the back of the head,” says Hershberger. Dee’s aggression continued throughout her illness, finally forcing Hershberger to seek outside care for his wife.

Medications for Alzheimer’s

Right now, medications for Alzheimer’s treat merely the symptoms of the disease. Aricept, Razadyne, and Exelon are cholinesterase inhibitors that help prevent the breakdown of brain cells. However, they cannot stop the damage and eventually lose effectiveness as brain cells diminish.

Namenda regulates glutamate, the chemical that involves brain functions, and treats moderate or severe Alzheimer’s disease. These drugs, says Healey, don’t treat the symptoms very well.

One of the newest drugs on the market that is believed to slow cognition decline, abucanumab, or Abuhelm, comes shrouded in controversy. As one of the first FDA-approved drugs for Alzheimer’s on the market in the last twenty years, it has shown some improvement in cognitive impairment and a decrease in beta-amyloid. But studies have been mixed. The drug is also controversial because of its annual price, estimated at $56,000. Medicare covers it only for patients enrolled in a randomized clinical trial.

Recently, the drug lecanemab, a type of immunotherapy, was granted priority review status by the FDA. This drug has been found to slow cognitive and functional decline by 27 percent in clinical trials. The FDA’s deadline for approval is January 2023. Nearing completion of clinical trials, Roche is now studying gantenerumab, an antibody treatment targeting beta-amyloid.

But if a patient is combative or aggressive, like Dee Hershberger, medication for treating these conditions caused by Alzheimer’s is unavailable. Instead, physicians have used psychotropic drugs even though they are not specially designed for treating Alzheimer’s disease and have side effects.

“They have FDA-approved medications for cognitive and functional problems,” says Healey. “We don’t have an FDA-approved medication for behaviors.”

![Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans use radioactive tracers (radiopharmaceuticals) to assess bodily functions and to diagnose and treat disease. “In highly specialized research centers for Alzheimer’s disease,” Healey says, “researchers have used the combination of beta-amyloid on the PET scan and blood or CSF [cerebrospinal fluid] biomarkers to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease.”](https://limestonepostmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/photo-PET.jpeg)

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans use radioactive tracers (radiopharmaceuticals) to assess bodily functions and to diagnose and treat disease. “In highly specialized research centers for Alzheimer’s disease,” Healey says, “researchers have used the combination of beta-amyloid on the PET scan and blood or CSF [cerebrospinal fluid] biomarkers to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease.”

Combativeness or aggression, too, can be unsettling and may create the most significant stressor for the caregiver and the patient. No one wants to see their loved one acting aggressively. For caregivers, it can be baffling and challenging to understand this behavior when they have known that person to be otherwise.

In his book, Hershberger recounts the day when Dee’s neurologist gave her a low dose of quetiapine, an antipsychotic. He hoped it would mellow her aggression and combativeness. She had been pushing him, fighting him, hitting him over the head, pulling hair, and throwing things at Hershberger, and he was at his wit’s end.

But when Hershberger checked the side effects of the medication, he found that it could cause depression, thoughts of suicide, or death if given to someone with dementia. So he called the neurologist and expressed that the drug increased her aggression. The doctor’s office suggested he take his wife to the emergency room if “you think she is in serious trouble.”

Several studies have examined the use of antipsychotics to treat aggression for Alzheimer’s disease. A 2006 study of 521 patients examined the effect of three antipsychotics — olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone — and concluded that the adverse effects of taking these drugs outweighed their effectiveness. Another side effect is that a patient can become sedate.

Eventually, Dee went to the hospital to manage her aggression and psychotic symptoms. There they began giving her some “heavy-duty” psychotic drugs, says Hershberger.

“Everything went to pieces then. When I went to that place, she was nearly like a zombie. She was just sitting in a wheelchair doing nothing.” Dee was a zombie when she left the hospital, says Hershberger, but she wasn’t when she went in.

Moving to a more dementia-friendly place

In Bloomington, there is a movement to become more dementia friendly as a community. Staff at restaurants, retail outlets, and government offices have undergone training to learn how to understand dementia and adjust their service options to account for dementia. Recently, the Monroe County Public Library sponsored a series of dementia-friendly films. These added efforts help to ward off isolation for those who have Alzheimer’s or dementia, as well as help to decrease the stigma surround the disease.

But at some point in the disease, most caregivers need more help. The question becomes what resources are available for families when they reach this point. Dayna Thompson has been a licensed mental health provider since 2006. The Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center that she leads serves eleven counties in the south-central region of Indiana. They provide support, resources, and information to those families dealing with Alzheimer’s. They also work on a community level helping to make community spaces and businesses more dementia friendly by providing training from Dementia Friendly Indiana.

Thompson believes the idea of living with Alzheimer’s and dementia is changing, and old stigmas are disappearing.

“Historically, working with people living with dementia has been a medical approach, giving the patient resources, medications, and then basically prepare them for the end,” says Thompson. “We are trying to shift the stigma that people with dementia have nothing to give.”

Moving away from the medical-only care plan has been critical. At ADRS, patients can find support groups, nutrition direction, and education classes about managing their disease and its progress. Caregivers can also get support.

Na’Kia Jones-Clark, Endwright Center Activities & Programming Manager at Area 10 Agency on Aging, says “700 to 800 local seniors” use their services. | Courtesy photo

Area 10 Agency on Aging provides similar services, says Na’Kia Jones-Clark, Endwright Center Activities & Programming Manager in Ellettsville. “We have 700 to 800 local seniors, mostly women, with an average age of 74 to 75, using our services. They come for balance, fitness classes, daily mall walks, and even music classes.”

Many seniors are now looking to diet, exercise, and increased social engagement as a way to prevent cognitive decline. This so-called lifestyle movement has contributed to the lower incidence rate of Alzheimer’s in recent years. For instance, recently, a study found that just taking a daily multivitamin can reduce a person’s risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

A 2019 study chronicled in the journal Alzheimers and Dementia looked at 154 healthy people, 35 with mild cognitive impairment and 119 with no symptoms of memory loss but less than perfect cognitive tests. After sticking to their personalized recommendations for eating and exercise, they found that most patients showed significant improvements compared with their baseline report.

‘Death with Dignity’ laws

Despite the continuing efforts to figure out how to live with Alzheimer’s, there are people who, knowing the prognosis, do not want to continue living with it. They don’t want to burden their family, or they want to go out as themselves rather than as someone who no longer recognizes themselves in the mirror. So they decide to end their lives.

According to a 2018 Gallup poll, 72 percent of Americans believe that euthanasia should be legal and that doctors should be able to help patients die. Only eleven states have physician-assisted suicide or medical-aid-in-dying laws. These so-called “Death with Dignity” laws vary within these eleven states, but their similar requirements are as follows:

- Must be an adult

- Must be a state resident (except for Oregon, which now allows out-of-state residents)

- Must be mentally capable

- Must be able to self-administer and ingest medications

- Must have a terminal diagnosis with the prognosis of death occurring within six months or less.

Because Alzheimer’s is not considered a terminal disease and a person must be mentally capable and able to self-administer and ingest medications, it does not fall within these requirements. Despite attempts since 2017 to enact Death with Dignity legislation, Indiana has no such law.

Amy Bloom says her husband, Brian Ameche, was resolute about ending his life after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. He also wanted her to write about it. Bloom chronicles their heart-wrenching journey in her new book, In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss (Penguin Random House, 2022).

Novelist Amy Bloom’s husband, Brian Ameche, decided to go to Switzerland to end his life after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Bloom chronicles their journey before and to Switzerland in her new book, In Love: A Memoir of Love and Loss.

Bloom and Ameche had been married for thirteen years when he began to have trouble with things like using a printer or understanding a computer calendar. In the book, Bloom describes learning of the diagnosis as the moment she could feel their infrastructure crumbling.

“I think, like most people, if you are a caregiver for somebody with a dementing disease, that the diagnosis is best understood in hindsight,” says Bloom. “You recognize all the things that you’ve been noticing and accommodating, ignoring, or explaining away.”

Once Ameche received his diagnosis, he was unequivocal. He wanted to end his life. Then he asked for her help and asked her to later write about the experience. “He was so clear about his decision, unwavering and at peace with it,” she says, “that I supported it.

“I did tell him at the beginning that he didn’t have to go that way, that he could stay home,” says Bloom. “He could stay with me. I would take care of him. I would protect him or keep him home as long as possible.” But he was resolute, she says. “And I understood his decision.”

So they traveled to Switzerland to a place called Dignitas, where, for $10,000, Ameche could die with dignity. They borrowed the money and began the arduous process requiring psychiatric evaluations, multiple neurologic tests, and many other records.

In January 2020, they traveled to Switzerland. There, Ameche swallowed a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital while Bloom sat with him and held his hand.

“Dignitas was peaceful, painless, and legal, and what we were looking for,” says Bloom. “Something, somewhere I could be with him in the end.” According to Bloom, it is unfortunate and inhumane that these options don’t exist in the U.S., saying, “We really need to have these conversations in America.”

Healey, at the Center for Healthy Aging, agrees. “We have not faced it. It’s an ethical issue, but as a society we don’t offer these options, and I think that is going to be the ethical issue because there will be more and more people faced with these issues,” he says. “We will have to face that, and it will be a tough dilemma.”

Hershberger faced the same dilemma. His wife, Dee, repeatedly asked him to help her die. “I couldn’t help her kill herself,” he says. “Alzheimer’s is a slow way for somebody to die.” His own dog, he says, didn’t suffer when they had to put him down. “But here we are willing to put them [Alzheimer’s patients] through this torturous existence for years. That seems so inhumane to me.”

End-stage options for Alzheimer’s

Most people with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease do not realize that they are at the end stages of their life. By that time, their faculties have declined significantly. They may be wheelchair-bound or bed-bound, needing full-time care. Often, caregivers realize they can no longer care for their loved ones at home. Some families seek outside options like memory care units or skilled nursing care. For some, palliative or hospice care may become their final option.

IU School of Medicine’s Dr. Kathleen Unroe says more geriatricians, nurses, nurses’ aides, and personal care workers need to be trained for a wide range of behaviors, to work with patients at all stages of their disease. | Courtesy photo

According to Unroe at the IU School of Medicine, using hospice to receive palliative care services is the primary pathway for end-stage Alzheimer’s patients in a skilled nursing facility. Unfortunately, Unroe believes that “hospice continues to be an imperfect fit for people with dementia as it can be difficult to predict prognosis or life expectancy, even in the later stages of the disease.” To be eligible for a Medicare hospice benefit, says Unroe, a patient must elect hospice care.

In addition, under Medicare Part A, a patient must be certified by the hospice doctor and the patient’s doctor that the patient is terminally ill with a life expectancy of six months or less, accept palliative care, and sign a statement choosing hospice care over other Medicare-covered treatments. Medicaid patients in the nursing home must have a prognosis of six months or less for hospice services to be considered medically necessary. A Medicaid patient in a long-term care facility can elect Medicare Part A hospice benefits. If they elect to stop hospice care, they then go back on Medicaid.

If palliative care consultations were more widely available, Unroe says, they could serve more residents in nursing homes or assisted-living facilities. Along with Dr. John Cagle of the University of Maryland, Unroe is running clinical trial funded by the NIH, called UPLIFT-AD (Utilizing Palliative Leaders in Facilities to Transform care for Alzheimer’s Disease) in nursing homes to test a model for delivering palliative care.

“Our hope is that working closely with these nursing home partners and palliative care consultants, we will be able to demonstrate an impact on the quality of life and quality of care for residents with dementia and describe practical approaches for implementing palliative care in this setting,” Unroe says.

Indeed, the stigma of living with Alzheimer’s is easing, especially in the early stages. More services, drugs, and increased care options and resources are available. But in Hershberger’s last moments with his wife, “she looked me in the eye and wouldn’t let go of my hand,” he says, knowing that she was going to die. “She never opened her eyes again.”

For most patients and their caregivers, it’s the long goodbye that is the hardest, making finding that ultimate cure all the more significant.

Read more stories from our health series by Rebecca Hill:

Monroe County, IU Preparing for Monkeypox Virus

988 Mental Health Lifeline to Include System of Care

Cancer Requires a Continuum of Care — and an ‘Army’ to Defeat It

Preparation vs. Security in Preventing Mass Shootings

What Happens When an Opioid Epidemic Collides with the COVID Pandemic?