My son Samuel was nearly two and a half when he learned to walk, still mastering how to balance himself and move his feet forward. His physical therapist with First Steps had arranged for Samuel to get a reverse walker: a tiny, toddler-sized metal frame with wheels and handles to grip.

At age two and a half, Samuel was eager to explore the world beyond his home, with the independence offered by his walker and the safety provided by sidewalks. | Courtesy photo

The initial freedom of our home’s hallway became routine after a few weeks. As with any toddler, the world beckoned. In the mild April weather, Samuel ventured down the driveway to the sidewalk. Turning left, he gripped the walker and eagerly hurtled himself down the block. I hustled behind him to keep up.

With the independence offered by his walker and the safety provided by sidewalks, he excitedly traveled nearly a mile from his home. Finally, he slowed when he reached his unvoiced destination: the playground at Bryan Park.

Samuel was learning to walk, but it was more than that, too. He was moving himself from the private space of his home and family to the public space of the sidewalk, the neighborhood, and the local park. He was not only exploring the world around him, but he was becoming a visible part of it as well.

Invisible Neighbors

There is a long history in this country of housing and exclusion, creating walls both real and virtual between “us” and “them.” Why do we allow people to become invisible in our community? Who are our invisible neighbors?

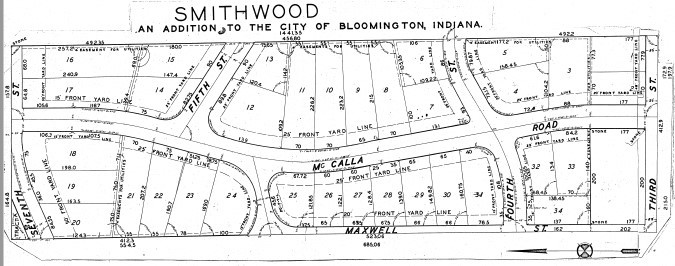

Housing discrimination was once more explicit and personal. Starting in the 1920s and ’30s, real estate documents regularly included discriminatory racial housing covenants that were legally accepted and enforceable. Racial covenants often still exist in present-day home deeds, although they are now illegal and unenforceable, thanks to the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Today, zoning that restricts neighborhoods from building anything except a single-family detached home — widespread in cities and suburbs nationwide — is increasingly recognized as an exclusionary legal tool that achieves de facto discrimination. Examinations of the impacts of single-family zoning highlight problems such as an artificially restricted housing supply that pushes up housing prices, limited housing options that exclude lower-income and Black families, and environmental impacts, such as more sprawl and automobile dependency.

‘No Negro, Mulatto, Chinese, Japanese, or person of any race or mixture of race except the members of the pure white race shall acquire title to any lot or building.’ Source: Smithwood Plat, Bloomington, 1947

More recently, state and local governments that are seeking to add to neighborhood housing options have been eliminating exclusive single-family zoning, including Minneapolis, Oregon, and Berkeley, California.

Many others are tentatively exploring how to do this, including the update of our own City of Bloomington’s zoning code, the Unified Development Ordinance (UDO). Bloomington’s UDO provides the regulations to implement the adopted Comprehensive Plan, which provides a long-range plan for the city’s land use and development through 2040. The UDO will guide development incrementally over the next 15 to 20 years. The final step, this spring, is the update to UDO Official Zoning Map, with review by the public and the city’s Plan Commission and Common Council. The first Plan Commission public hearing is scheduled for the March 8, 2021.

These proposed zoning updates are not without debate, locally or elsewhere. Community members raise concerns about changing the character of the neighborhood, whether housing values will go up — or if property values will drop, sufficient space for parking cars, and whether opportunities for homeownership will increase or dwindle.

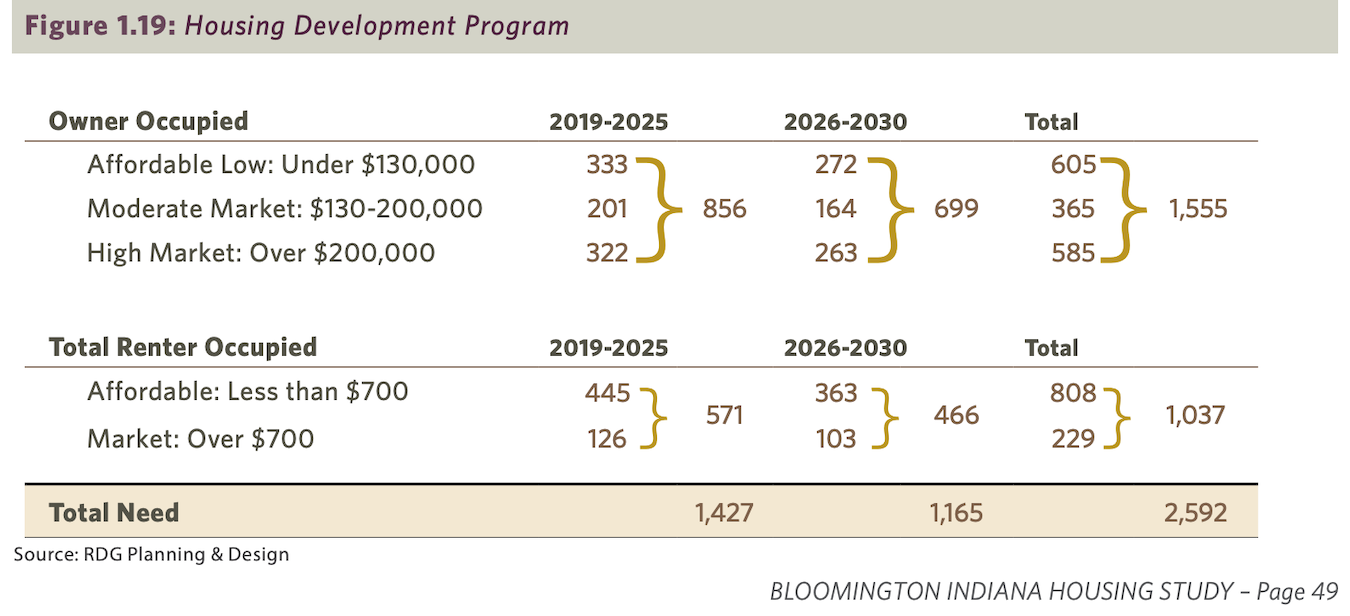

Yet, Bloomington continues to grow and thrive — and with it, demand for housing. According to the Bloomington Housing Study, produced by a consultant for the city and published in July 2020, in the next decade the city will need 1,555 new for-sale homes and 1,037 new rental homes for a wide range of incomes and affordability.

According to the Bloomington Housing Study, published July 2020, in the next decade Bloomington will need 1,555 new for-sale homes and 1,037 new rental homes for a wide range of incomes and affordability.

According to “Working Hard, Falling Behind: A Report on Affordability,” by the Bloomington City Council’s Affordable Living Committee (on which I participated), the City of Bloomington has convened at least three task forces over the past 25 years to look at the problem of affordable housing. In that period, housing supply has not kept pace as the population has grown — and housing prices have gone up while wages have remained flat.

Producing enough housing to meet predicted demand — especially in a useful mix of types, prices, and locations — is key to addressing local housing challenges. We can’t have affordable, accessible housing if we don’t have enough homes for everyone, as Shane Phillips notes in the book The Affordable City: Strategies for Putting Housing within Reach (and Keeping It There).

So, where will this housing go? Who will build it? How can the city encourage and support meeting these target goals? These are the questions that we, as a community, must consider.

Updating zoning to allow more residential diversity in our neighborhoods isn’t going to solve housing challenges with speed or simplicity — but it is an important step in the right direction.

“I think it’s harder for folks to see the discriminatory aspect of single-family zoning here in Bloomington, in part because we’re so white here: four percent Black population versus ten percent for the state as a whole,” says Dave Warren, with Neighbors United Bloomington/Monroe County. “But people don’t think about what our population might look like if Bloomington hadn’t instituted single-family zoning about three decades ago.”

I’m grateful to the generosity of those who have shared their housing stories here, and originally on NeighborsUnited.info. While these housing stories are true, some names, pronouns, and images have been changed in the interest of privacy. These are only a few housing stories. There are so many more stories in our community that are still invisible.

Making Neighbors Visible

Alex: The support of neighbors and living near friends

Alex works for Indiana University and has rented in core neighborhoods around Bloomington for the past ten years. They consider themselves a “relatively privileged white person.”

When Alex first moved to Bloomington, they had a difficult time finding housing. Many apartment buildings wouldn’t rent to Alex — because they were not a student.

Alex finally landed a rental home in Bryan Park and fell in love with Bloomington. Living solo, they paid $850 per month plus utilities for a two-bedroom, one-bath house with “quirks.”

Later, to save money on rent, Alex found two roommates and moved to Prospect Hill. There, each roommate paid $400/month plus utilities.

Next, Alex moved to an apartment in Maple Heights and has now lived for several years in Green Acres. Alex is tired of moving and wants to own their own space.

But Alex worries that they can’t afford the mortgage payments with an annual salary of $60,000. Even the lowest-priced homes in the core neighborhoods — which often start at $250,000 — still need lots of work.

Alex will continue to rent in these neighborhoods while saving for a down payment because they want to live close to downtown, to walk and bike to work. Alex likes the walkable streets and the support of neighbors, and they want to live near friends.

“I want to simply be able to hang items on the wall without fear of egregious costs at the end of my lease. I don’t have wealthy parents who can help with a down payment. I have student loans, I’m saving for retirement, and I live frugally.” —Alex, Green Acres

Sam: Living on the outer limits

Sam has lived in Bloomington/Monroe County since 2000 and has both owned and rented here. Rent has always been higher than the cost of Sam’s mortgages.

Even with a social services salary in the higher range for Bloomington, Sam has only been able to buy outside of the city limits or just on the edge.

“I would love to have the option to bike, use public transportation, or walk, but have not yet been able to afford a home with those options. I am horrified that in a town with so many resources those in power make the choice to make housing unaffordable and inaccessible to so many.” —Sam, Broadview

Housing Goes Missing

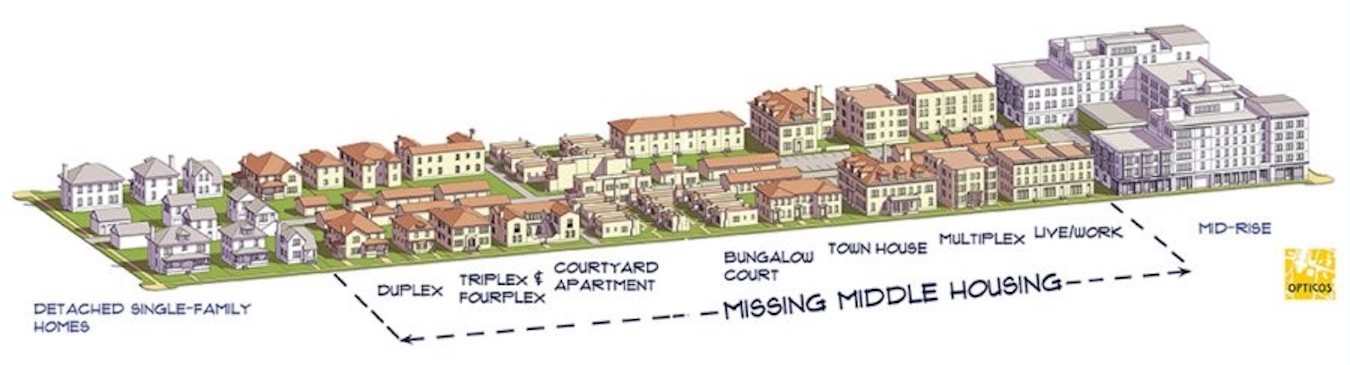

Some of the housing we need can be readily tucked into existing walkable neighborhoods. Early 20th-century neighborhoods often accommodated a mix of compatible housing options — single-family homes as well as duplexes, fourplexes, cottage courts, and courtyard buildings. But in the decades since World War II, residential development in Bloomington, as in much of the country, has focused on single-family detached homes or large apartment buildings.

The historic small-scale multiunit or clustered housing types, often called “Missing Middle Housing,” a term coined by architect and urban designer Daniel Parolek, is ready for a return. Missing middle housing can respond to shifting household sizes and meet the growing demand to live in walkable communities that are close to transit, jobs, schools, and more. Adding back more missing middle housing also adds more homeownership and rental housing choices that are less expensive than a single-family detached home.

‘Missing Middle Housing’ represents the middle scale of buildings between single-family homes and large apartment or condo buildings. | Illustration courtesy Opticos Design

Yet, several significant demographic shifts have changed how and where Americans live. The number of “nuclear family” households — with two parents and kids — has been shrinking, while demand for multigenerational living and aging in place is rising. Unfortunately, the nation’s real estate, propelled by restrictive zoning that favors larger single-family homes, hasn’t kept pace with demand for a broader range of more affordable and diverse housing options.

In the Bloomington Housing Study’s “Housing Affordability and Availability Analysis,” the report indicates that “Young professionals often noted difficulty in finding units affordable that met their specific needs.” Sixty-nine percent of millennials (age 23-38) say they are open to a smaller home as long as it meets their needs. Making it easier to add duplexes, triplexes, or other missing middle housing in Bloomington can help provide needed options.

A recent study from the Urban Institute has also shown that neighborhoods with a mix of housing types (i.e., single-family homes, duplexes, multifamily buildings) not only promote more racial and income diversity but also offer households greater stability in economically uncertain times.

Making Neighbors Visible

Kris: Accessibility challenges

It can be exceptionally challenging to find an affordable, wheelchair-accessible place to live, on a bus line, and with safe access to a bus stop.

Kris has had cerebral palsy since birth and has spent their life using braces, crutches, and now a motorized wheelchair to get around. They depend on the public transit system for transportation and must organize their life around its boundaries, hours, and rules.

A friend of Kris’s shared their experience finding a new place when they were in urgent need of housing.

One place, a one-room studio with cinderblock walls, was barely accessible. But it was affordable, well maintained (though way overpriced for a studio), and available right away. Kris had to have a friend co-sign, because their credit score was too low.

The Bloomington Housing Study (2020) predicts that the city will need more than 1,000 rental units and more than 1,500 owner-occupied homes in the next decade. B-Line Heights (pictured), an affordable rental housing project on North Rogers Street, has 34 units. | Limestone Post

But the studio had no sidewalk access to get to the nearest bus stop, 20 minutes away. This meant that in order to go anywhere, they had to arrange 24 hours in advance for a special bus to pick them up, and had to pay extra for this door-to-door service. This limited their mobility severely and meant that they usually only left to go to work and come home. No more spontaneous outings, running to the store and back, visiting a friend. Every move had to be planned in advance.

Finally, after an unreasonable amount of confusing communication, mixed messages, mistakes, frustration, and tears, Kris found an accessible, affordable unit to rent. They had to purchase their own washer and dryer, which they did through a predatory lender, but overall, it was a better place to live. Access to public transportation, and proximity to the B-Line Trail, has increased their mobility and access to the grocery store.

Kris has had to navigate these systems their whole life, and will continue to do so, day by day. Right now, they are dreaming of homeownership and have looked often at trailer parks and houses, trying to find something within city limits, hoping for some sort of rent-to-own/buy-on-contract situation. They aren’t sure when they will have the down payment or credit score they need to purchase a home.

Jan: Building equity in the neighborhood

Jan’s parents were able to purchase their first house because they added an apartment to the basement. The rent from the extra unit helped pay the mortgage — and allowed Jan’s hard-working parents to accumulate wealth and invest their money. Their parents often looked for a tenant who could do after-school care for Jan and their sister, and they would offer a discounted rent in exchange. Jan’s special-needs sister eventually moved into a duplex so she could live semi-independently as an adult.

Jan enjoyed growing up in a neighborhood where people of all ages, incomes, colors, and cultures would mix together. She shared many things with neighbors — like playing in backyards, gardening, celebrating holidays, childcare, making art, getting haircuts, and even meals.

“In my mind, saying ‘yes’ to plexes includes saying ‘yes’ to different definitions of ‘family,’ to allowing for more equitable access to wealth accumulation, and to the possibility for differently abled people to live safely and semi-independently in downtown neighborhoods. I think our neighborhoods would benefit, not suffer, from the thoughtful expansion of options for multifamily housing.” —Jan, Bloomington

Housing in a College Town

Yet, housing takes on an additional layer of complexity in a city like Bloomington with a large university. IU’s first dormitory, on the Seminary Square campus, opened in 1838. IU construction of new residence halls grew rapidly post-World War II, but then tapered by the 1960s, fostering demand for off-campus housing options as baby boomers entered college and made a mark on the local housing market.

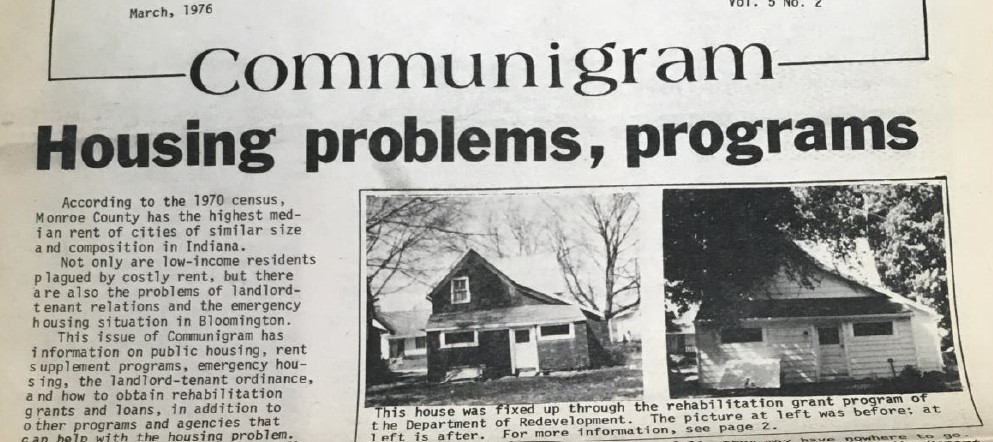

High housing costs and insufficient emergency housing have been issues in Bloomington for more than 50 years. Source: Communigram, Monroe County Community Action Program, March 1976

According to the 1970 census, Monroe County had the highest median rent of cities of similar size and composition in Indiana. Other issues included managing landlord-tenant rights and responsibilities, and insufficient emergency housing in Bloomington.

Today, IU has the capacity to house about 13,000 students on campus, or slightly less than one third of the total student population.

The City of Bloomington, like local governments in many other college towns, must regularly evaluate how to balance the need for housing for students living off campus while also maintaining the quality of life and affordability for long-term residents.

Municipalities around the country with significant university populations can deploy a variety of tools to help manage these needs, including zoning codes, rental ordinances, university policies, community land trusts, and collaborative agreements between schools, the city, or a community civic organization.

Making Neighbors Visible

Adria: A place for a meaningful, young adult life

For Adria and others living with disabilities, walkable neighborhoods and transit options near downtown Bloomington offer easy access to necessities like grocery stores, emergency services, and pharmacies. | Courtesy photo

Adria was diagnosed with multiple disabilities at birth. Driving is not a viable option, and will never be. In 2008, just before her senior year in college at Brescia University in Owensboro, Kentucky, she moved to Bloomington to attend a transitional independent-living skills program for young adults with autism spectrum disorder and learning disabilities.

She returned to Brescia to finish her senior year. After graduation, she explored where she could move to enjoy a meaningful, young adult life. Her checklist:

- Nearby necessities like grocery stores, emergency services, and pharmacies

- Accessible to people with disabilities

- Pedestrian friendly

- Public transportation

- Social opportunities for young people

It turned out that downtown Bloomington met all of these requirements, so she chose to return after graduation. Her family could help support the high cost of living.

“For those with disabilities, the easy and affordable access to the things that a small city offers — many of which are day-to-day necessities — should not only belong to those in the upper-middle class but to all as a given right regardless of income. Nationwide, one in four Americans with a diagnosed disability live at or below the poverty level. We have got to make Bloomington a more equitable city for all people to live and enjoy life.” —Adria

Dave: Moving out of the city

When Dave and Rachel moved to Bloomington in 2009, they were able to buy a small townhouse in the Sherwood Hills complex on the south side of town. Neighbors were a mix of young and old, retirees and working professionals, graduate students, Black, white, Hispanic, Asian.

They could walk two minutes to a #1 and #4 bus stop, or about ten minutes to a #7 bus stop. They had one car that they hardly used because of the proximity to transit.

Then two kids came along (and all the things that go along with two kids). Dave and Rachel needed a little more room.

When they put their condo up for sale in 2017, it was one of the few affordable units on the market. They received three full-price offers within 24 hours. (Three years later, the same condo is still one of the more affordable ownership opportunities in the city, but it’s now selling for more than 30 percent more.)

But Dave and Rachel quickly found they were priced out of anything remotely close to any of the city’s walkable neighborhoods. They made offers on two different houses that fell through. Other homes in their price range would have required tens of thousands of dollars in work to make them safe and livable.

Finally, they found a place: a single-family home that they love, in Monroe County, west of I-69. Their neighborhood also includes many new duplexes, occupied by homeowners and renters, home to families young and old.

“Double-digit percent increases in home prices every year might sound great, but it’s only great if you’re lucky enough to be in the minority of people in Bloomington who already own a home. For renters or would-be buyers, those increases just mean fewer options and more folks moving further away.” —Dave, Monroe County

Needed: More Equity for Residents’ Voices

Bloomington has 65 neighborhood associations that are spread throughout the city. However, these are private organizations that choose their own boundaries and bylaws — and they do not include all city residents.

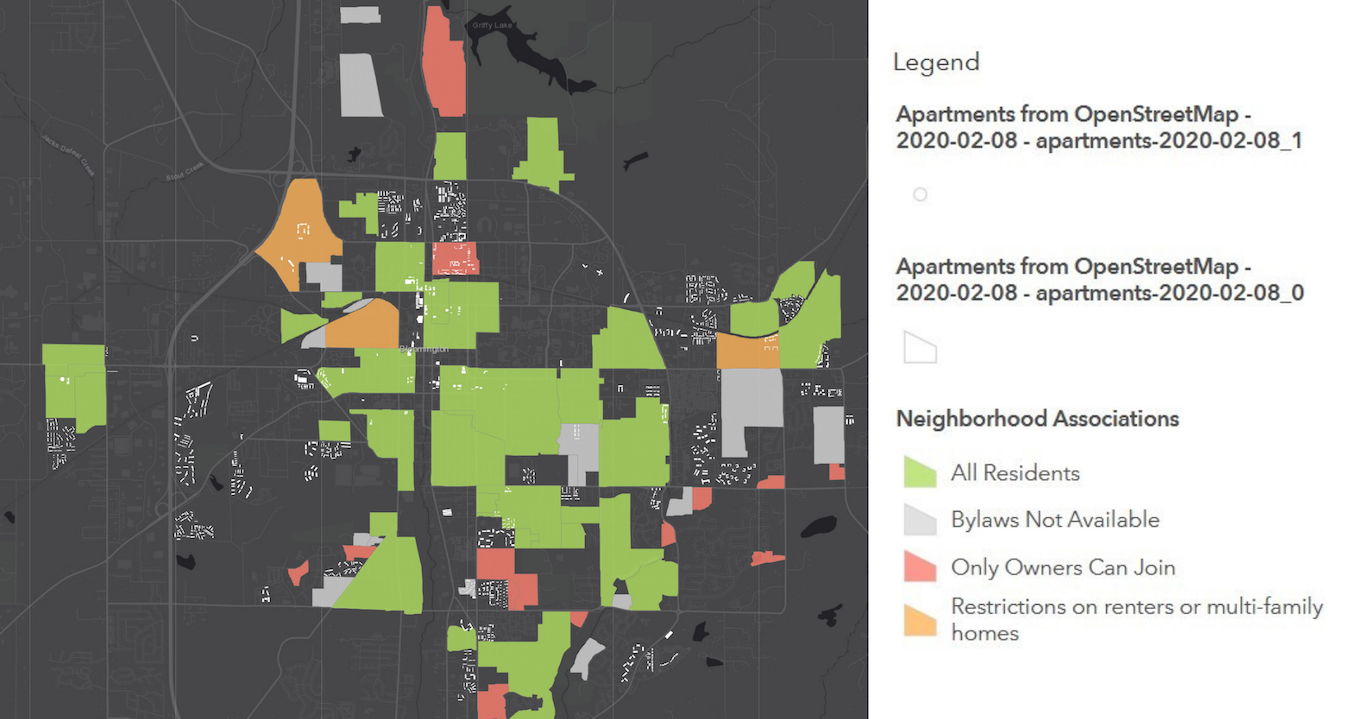

Neighbor Associations and Housing Equity, a StoryMap with interactive images and descriptive text created by Mark Stosberg, shows how Bloomington’s neighborhood association boundaries bypass many of the city’s multifamily properties. In addition, an examination of neighborhood association bylaws (also linked in the map) shows how some associations have restrictions or exclusions on renters or multifamily homes.

Yet, feedback on local land uses and zoning questions frequently comes via neighborhood associations. The staff of the City of Bloomington’s Housing and Neighborhood Development Department (HAND) provide neighborhood associations with tools and resources to facilitate communication between neighborhoods and city departments. HAND’s Neighborhood Services program offers technical support services to neighborhood associations within the city limits of Bloomington.

“In neighborhood associations, it often felt to me like our voices didn’t matter as much as homeowner’s voices. As renters, we were the residents the homeowners wished were not there. Never mind that some of them own rental property themselves — sometimes in the same neighborhood,” according to K., a resident of McDoel Gardens.

So, it’s critical to understand that these associations don’t represent all residents of Bloomington. What they primarily represent are non-apartment dwellers — in a city where the population is 65 percent renters.

This StoryMap, ‘Neighborhood Associations and Housing Equity StoryMap,’ by Mark Stosberg, illustrates neighborhood association boundaries compared to rental properties. It highlights a pattern of exclusion of many large apartment buildings throughout the city. Apartment buildings are white, neighborhood associations are colored and labeled in the legend. | StoryMap by Mark Stosberg. Sources: neighborhood data from City of Bloomington; apartment data from OpenStreetMap.

(left) In northeast Bloomington, the Eastern Heights Neighborhood Association surrounds, but does not include, the Meadow Park Apartments. (right) Sherwood Oaks and Sunny Slopes Neighborhood Associations are colored green because any resident may join — as long as they live in the boundaries of the association. Peppergrass Neighborhood Association is in red to indicate only property owners are eligible to belong. Numerous apartments are shown along South Walnut Street Pike. | StoryMap by Mark Stosberg. Sources: neighborhood data from City of Bloomington; apartment data from OpenStreetMap.

Making Neighbors Visible

Tim: The price of living in a historic district

Tim arrived in Bloomington in 1982 to attend Indiana University. He has experienced a variety of housing options over the past four decades, each reflecting different times in his life and what he could afford at that time. The past 38 years included sleeping in a closet in an Elm Heights summer sublet, a post-divorce single room in a rooming house in the Old Northeast neighborhood, and presently a small two-bedroom home on the Near West Side.

Having rented in several core neighborhoods, Tim dreamed of having a small house close to downtown where he could walk or ride his bike to work, businesses, and events. Historically, many families in these neighborhoods had boarders and extended family members who shared their homes. Many of the old plexes that dot these neighborhoods were built to cater to a varied population of workers, students, and residents who wished to be near downtown.

In 2000, Tim was able to purchase an older home through an affordable home buying program. His down payment came from leveraging his meager savings with a grant and family support.

But homeownership — especially of an old house in a core neighborhood — isn’t for everyone. Tim’s older home has required many repairs that became more costly because they also needed to comply with restrictive historic guidelines and covenants.

“All of these experiences have informed my opinion that there continues to be a need for diverse housing options in core neighborhoods. As some folks push for continued single-family-only zoning under the auspices of retaining the ‘old’ neighborhood, they should keep in mind that it doesn’t reflect the true history of the neighborhood.” —Tim, Near West Side

Baby Steps

We are fortunate that Bloomington and Monroe County are a big draw for people and employers. But if we don’t make it easier to add more housing options, the growing population will keep spreading out, eating up more rural land in the county. Plus, adding the opportunity for more households in Bloomington’s more walkable, transit-connected neighborhoods can support a more sustainable economy and reduce car dependency.

Removing exclusionary zoning is also a land use policy that is still under local control. The State of Indiana has repeatedly preempted the ability of local governments to adopt equitable housing policies. A successful strategy to achieve affordable and accessible housing must be a multipronged effort that leverages local capacity to address housing supply, stability, and subsidy. For example, to address critical housing issues, the American Planning Association’s recently revised Housing Policy Guide encourages robust community engagement, an equitable planning process, and exploration of innovative ideas for housing finance.

Ultimately, reauthorizing duplexes and other small-scale multifamily housing in Bloomington’s neighborhoods is a relatively modest step to fulfill actual housing needs.

To tackle these challenges, Bloomington and Monroe County need to draft a comprehensive housing strategy, backed by a strong, diverse coalition of public officials, policy makers, planners, developers, advocates, renters, and homeowners.

“Over the last several decades, housing costs in Bloomington and Monroe County have been making headlines,” says Vauhxx Booker, an organizer with Neighbors United Bloomington/Monroe County. “An increasing number of households are scrambling to pay their mortgages and rent, and an ever-growing number of residents face the uncertainty of eviction — or even homelessness. While our local governments cannot solve all these challenges, they do have a critical role in addressing them. Smart governance can help mitigate these effects and provide a measure of relief to many in our community.”

It won’t be easy, but we’ll have even bigger housing issues related to affordability, accessibility, racial inequity, and climate change challenges later if we don’t tackle necessary changes now. And the pandemic has magnified the urgent need for housing stability.

Samuel: Taking the bus home

Samuel is now 18. He loves jazz, opera, Facetime with friends, and is a big Green Bay Packers fan (Colts, too). He can tap out a message on his phone for people who don’t understand American Sign Language.

Deborah Myerson (left) and Samuel, who is now 18. He loves jazz, opera, Facetime with friends, and is a big Packers fan (Colts, too). | Courtesy photo

He has been walking unassisted since he was four, but he still needs help with other daily living skills like bathing, dressing, and cooking. In addition to walks in the neighborhood, he also loves to take the bus. Where we live in Elm Heights, we are fortunate to live near the #4 and #5 bus lines that can take him downtown to the library, east to the shopping mall, or south to the Winslow Sports Park for baseball games.

Samuel can live with us as long as he wants, but he is also eager for more independence. As he gets older, it would be great if he could live nearby, perhaps in half of a duplex with a roommate. Never one to be shy, he welcomes being a visible part of the community.

Together, we can create an inclusive community — and never allow anyone to be invisible again.

[Editor’s note: The City of Bloomington Plan Commission will consider the adoption of a new Zoning Map at a public hearing on March 8, 2021, at 5:30 p.m. Members of the public may attend via Zoom with this link.]

For Further Reading

The Affordable City: Strategies for Putting Housing Within Reach (and Keeping it There), by Shane Phillips. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2020.

Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today’s Housing Crisis, by Daniel G. Parolek, with Arthur C. Nelson. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2020.

Where We Live: Communities for All Ages: 100+ Inspiring Ideas from America’s Community Leaders, by Nancy LeaMond. New York: AARP, Time Inc. Books, 2018.