Since the election of Donald Trump to the White House in 2016, much of the journalistic and academic spotlight has been focused on how Trump’s ascension to the presidency is reshaping the national Republican Party and the degree to which the nationalist and nativist forces unleashed during the 2016 campaign will reshape American politics in coming electoral cycles.

As president, Trump has become the de-facto leader of the GOP. Although by most accounts Trump governs more like a traditional conservative, his populist and anti-immigrant rhetoric is driving the Republican Party to the political extremes. Trump’s words and executive actions have also, in many ways, radicalized the Republican base. Since taking federal office, more than 30 moderate and traditional Republican conservatives have either resigned or forfeited reelection, including Speaker of the House Paul Ryan. This has paved the way for more Trump-like politicians to participate in — and potentially win — upcoming electoral contests.

Yet, the 2016 election was not just consequential for the Republican Party. The 2016 Democratic primary campaign and subsequent convention held in Philadelphia revealed deep divisions within the ranks of the party leadership regarding the policy platform of the party. It also exposed the widening differences of opinion among the Democratic base as to whether the party should follow a more progressive economic agenda or continue to engage in the politics of the “culture war” over polarizing social issues such as racial equality, LGBTQ rights, reproductive rights, and immigration.

Bernie Sanders won 22 primary contests during 2016. This greatly increased the political influence of the progressive wing of the party. Although Clinton and the Democratic Party leadership attempted to bridge the divide between more traditional “establishment” Democrats, progressives, and party activists, deep fissures within the party over policy priorities continue to function as an obstacle to party unity.

Mark Fraley, chair of the Monroe County Democratic Party. | Courtesy photo

Recent developments in the national Democratic Party are impacting liberal and Democratic voters, politicians, and candidates in the state of Indiana. These developments raise many questions.

How are Indiana Democrats responding to shifts in the policy stances of the Republican Party — especially on issues related to race, minority rights, and economic nationalism? And to what degree are the divisions within the national Democratic Party reflected and mirrored by local liberal and progressive circles?

And now that the Indiana primaries are over, how will Indiana Democrats respond to the negative stereotypes associated with the Democratic Party? How will Indiana Democrats cope with or fight against the new politics of white ethnic nativism? Will Indiana Democrats reach out more to rural, blue-collar, and working-class Hoosiers, or will candidates and officials continue to concentrate on the party’s urban strongholds across the state? What is the significance of Bernie Sanders’ primary victory in the state, and what does that victory mean for the upcoming 2018 midterm election?

Mapping the political terrain

Over the past two decades, Indiana has achieved a reputation as a conservative bulwark in American politics. The state has passed some of the most conservative legislation in the nation on abortion, refugees, immigrants, and LGBTQ rights. Indiana has become a repository for conservative policy experimentation as the state’s conservative leadership has implemented legislation aimed as excluding minority groups from the state’s economic and social life. The chair of the Monroe County Democratic Party, Mark Fraley, explains that “Indiana is tough terrain for liberals and Democrats. Republican efforts at redistricting and gerrymandering have been very effective in the state of Indiana, which has made it difficult if not impossible for Democrats to compete. Additionally, the current political climate across the state is not one that favors Democrats.”

Yet, taking a broader historical view, Democrats in Indiana have experienced significant moments of electoral, legislative, and policy successes. Indiana Democrats controlled the Indiana House of Representatives for 13 of the past 25 years. State Democrats controlled the state governorship from 1992 to 2005. In 2008, Barack Obama narrowly defeated Republican challenger John McCain, carrying the state for the Democratic Party. More recently, Democratic candidates for the Indiana governorship and U.S. Senate performed rather well: Democrats John Gregg (Governor) and Evan Bayh (Senate), although both defeated, won 45 percent and 42 percent respectively of the popular vote in the state. Even more progressive candidates have won popular support in the state. During the 2016 Democratic Primary, self-proclaimed Democratic Socialist Bernie Sanders defeated Hillary Clinton, capturing 52 percent of the primary vote in the state.

Nonetheless, there appears to be a growing disconnect between the state Democratic Party and the voting public. In recent years, Democrats suffered from a series of debilitating stereotypes — cast as elitist, globalist, internationalist, and detached from the realities and lived experiences of the American working class. In his last press conference as president, Barack Obama noted that “People feel as if they are not being heard. Democrats are characterized as coastal, liberal, latte-sipping politically correct out-of-touch folks.” Polling conducted in 2017 suggests that the majority of the Americans question the degree to which Democrats understand the real problems facing working Americans.

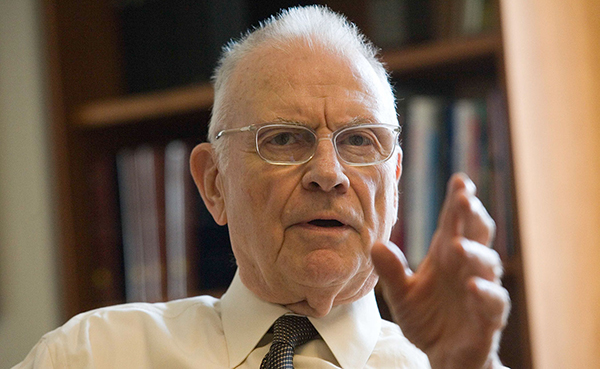

Former Indiana Congressman Lee H. Hamilton. | Courtesy photo

The gravitation of many working-class voters to Trump and other conservative candidates arguably cost the Democrats the election, especially in Midwestern swing states such as Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio. Evidence appears to be mounting that negative views of the Democratic Party and its ability to represent working class interests is, in part, a component part of this recent trend. Trump’s message of economic populism resonated with many constituencies that typically trend liberal, including union members, individuals with a university-level education, and women.

Complicating further the Democratic agenda, both in Indiana and beyond, is the racialization of Trump’s economic message and the emergent politics of white ethnic nativism (also known as white ethnic majoritarianism and white nationalism). White nativism is a political ideology where, in part, individuals feel that state institutions and welfare goods should serve only the majority, but that majority is often defined in rigid ethnic or racial terms.

The reemergence of white nativism in American politics post-2016 present Democrats with a number of challenges, given the emerging reputation of the Democratic Party as a party of minorities. “The new politics of white nativism pose a number of risks for the Democratic Party as it attempts to bring white voters back into the party,” says former Indiana Congressman Lee H. Hamilton. “There is a widespread perception among many that the Democratic Party has abandoned white people. Given that whites make up more than 70 percent of the population, this is a big challenge for Democrats. More and more people feel as if African Americans and Latinos dominate the party.”

Examining Indiana politics more closely

In addition to the branding issues facing Democrats, the party is deeply divided over which policy positions should take priority. On the one hand, the establishment wing of the party — those circles and political cliques long dominant in the party, led notably by Joe Biden, John Kerry, Chuck Schumer, Nancy Pelosi, and the Clintons — maintains a longstanding preference to engage in the politics of the “culture” war and the furthering of a socially and culturally progressive platform on the separation of church and state, women’s health issues including access to abortion services, and LGBTQ rights.

On the other hand, a more economically progressive wing led by Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren remains committed to a resurrection or reinvigoration of New Deal-era programs in addition to new legislation aimed at bolstering and expanding the American welfare system as a means of protecting working-class communities from adverse economic developments.

Today, it is unclear which direction the party will go: Will it sustain its culturally liberal policies or move in a more economically progressive direction — as recent candidate selection, especially in Indiana, suggests — or perhaps both? Either way, we can expect both policy platforms to experience significant issues, especially in Indiana, given its particular dynamic composition.

Ann DeLaney, former chair of the Indiana Democratic Party. | Courtesy photo

First, the state’s Democratic Party leaders and elected officials have already coalesced around an entrenched set of policy positions that trend significantly more conservative than those of the national party leadership. This is, in part, due to the role that state Democrats play as an opposition force in an area dominated by conservatives. “There are those who identify with Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — the more progressive wing of the party,” says Ann DeLaney, former chair of the Indiana Democratic Party. “But there are also many who are very conservative Democrats in the state — many who are much more conservative on economic issues than Hillary Clinton.”

DeLaney continued by noting, “In the state of Indiana, Democrats have such little power that the differences among the competing wings of the party are toned down. Countering the Republican supermajority is simply more important than in engaging in drawn out debates with each other. The need for Indiana Democrats to counter the policy moves of the Republicans forces state Democrats to be more united and cohesive.”

Second, Indiana’s overall political culture is one that does not favor many policies emanating from within the ranks of the liberal opposition. It shapes attitudes toward what individuals want and expect from government, and those policies are understood as the best for fostering and creating a “good society.” Such attitudes are influenced by two distinct yet interrelated dynamics, both undergirded by forces of political and ideological conservatism.

Hoosiers are fiercely individualistic and the political culture of the state is characterized by high levels of distrust in government. This individualism often translates into hostility or resentment for government policies that appear intrusive into the social or economic lives of individuals. Such a climate does not favor the kinds of progressive economic policies proposed by many Democrats. Government in this context is only understood as “good” when government functions and operates in sharply limited ways. Research has shown that highly individualistic political cultures like that of Indiana spend fewer resources on community goods such as education and healthcare.

Nonetheless, more Hoosiers may be won over to the Democratic cause if Democrats continue to show that government intervention can produce higher levels of social welfare. “It is true that many Hoosiers are skeptical of government and suspicious of government power,” says Fraley. “To me, the best way to show voters the benefits of government is to demonstrate and uphold good governance at the local level. Democrats need to continue to build strong mayors, strong townships, and strong city councils and demonstrate both competency and compassion. Democrats need to show people at the local level — where people are the closest to government through issues such as infrastructure, water quality, housing, and education — that Democrats have solutions to pressing problems. Whatever its flaws, local government is a place to come together to solve shared problems and build a strong community.”

Indiana’s political culture is also marked by a high degree of traditionalism. In traditionalistic political cultures, individuals feel that the role of government is to ensure, maintain, and defend traditional social relations by limiting the impact of cultural, social, or even technological change. In this sense, Indiana culture is marked by a distinct provincialism: that is, an aversion to outsiders and suspicion directed against government as an agent for social change. The kinds of culturally progressive policies supported by the Democratic Party, such as women’s rights, LGBTQ protections, or refugee resettlement, challenge the boundaries of traditional concepts of community.

Fraley says, “To me, the best way to show voters the benefits of government is to demonstrate and uphold good governance at the local level.” | Limestone Post

Throughout Indiana’s political history, community outsiders have long been non-whites, including African Americans and Native Americans, as well as immigrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers. At present, the state remains a prime location for white ethnic majoritarianism and racial agitation. For instance, 30 different white supremacist, anti-Muslim, or anti-LGBTQ groups operate in the state. Indiana Public Media reports that Indiana ranks 11th in the country in the number of white supremacist and anti-minority groups operating in local communities. Paoli, Evansville, Connersville, Terre Haute, Lafayette, Auburn, South Bend, and Indianapolis are all centers for white nationalism, the home of hate groups that sponsor marches, distribute racist literature, and promote anti-minority propaganda, protests, and public rallies. Although Indiana ranks among the least diverse states in the Midwest (87 percent white), a steady increase of non-whites into the state has coincided with a sharp uptick in the number of hate groups.

Although political culture in the state of Indiana is not one in which many Democrats can succeed politically, the party nonetheless serves as an important check on conservative policies. “Indiana Democrats have been very critical of deteriorations in the racial climate or moves by Indiana Republicans to promote racist policies such as the English Official laws of the 1980s, Pence’s refusal to settle refugees in the state, or Trump’s support for racially exclusionary policies,” says DeLaney. “Indiana Democrats fight hard against racist policies in the legislature and in the courts. Indiana Democrats are very united in this fight. Indiana, like most other states, has become more diverse in the past decade. There are over 100 languages spoken in the Indianapolis public school system. Racially antagonistic policies are simply out of step with reality.”

Looking forward

Among the largest challenges facing the Democratic Party in the Trump era will be courting working-class whites who appear — at least for now — to be firmly in the conservative camp. “Trump understood better than Clinton and other Democrats that whites are unhappy with the political system, felt marginalized and bypassed,” says Rep. Hamilton. “Trump skillfully played on the resentment of white communities toward demographic, social, and cultural change. It isn’t right to say that Clinton or other Democrats were unaware of it, but I don’t think that Democrats fully appreciated the intensity of it.”

De-emphasizing divisive cultural issues may prove to be a successful strategy. For instance, Rep. Hamilton noted that “Democrats need to focus on uniting the different factions of their party and the electorate. You don’t do that by emphasizing divisive issues like abortion and transgender rights. Democrats need to better position themselves not as a party of the establishment, but a party helping all people — regardless of race, class status, gender or sexual orientation — to get ahead in American economic life.”

Others, such as DeLaney, see no need for a drastic shift in the party platform. “It’s important to remember that we had a majority in the [national] election. We still have that majority. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote,” she says. “There is no need to change the fundamental doctrines of the party in order to reach out more to working class people. Some things we will not be able to do: change our stance on gun control or abortion. We can win back many white voters, but there are some ‘white’ issues with which we cannot contend. We cannot change our policy stance on some issues important to many white voters. We can, however, deliver more on those economic needs of Americans — many of which are white — with the right economic message.”