That to the domestic sphere, only, did the functions of womanhood belong; that woman had, and could have, no legal existence, apart from her husband; that she could not engage in business on her separate account, that her separate earnings belonged to her husband; that woman, from the delicacy of her nature, was unfitted for the activities of the sphere occupied by men. Such of these fictions as became a part of the law are rapidly disappearing, and few if any of them exist in Indiana. —Indiana Supreme Court, 1893

The Indiana Supreme Court wrote this when it proudly ruled in 1893 that Antoinette Dakin Leach, a Sullivan County woman, could practice law in Indiana. While the Indiana constitution said that any lawyer had to be a voter, and impliedly male because women couldn’t vote, the Indiana Supreme Court ruled this didn’t mean women couldn’t be attorneys.

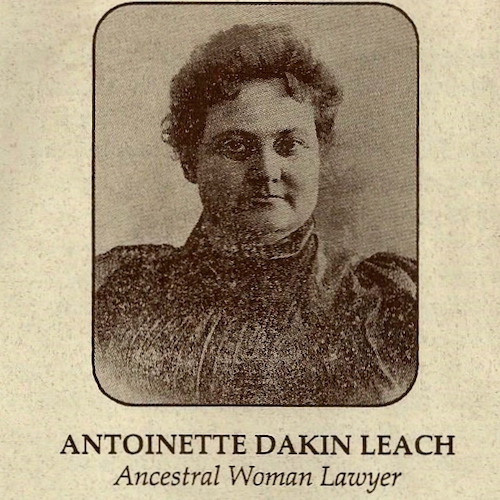

This photo of Leach, “Ancestral Woman Lawyer,” was included in a pamphlet “Celebrating the Indiana Centennial of Women in the Law, 1893-1993” from the Indiana State Bar Association | Image courtesy of the Sullivan County Historical Society

Emboldened by Leach’s success, a Tippecanoe County suffragist, Helen Gougar, became a lawyer as well, and in 1897 she petitioned the court to let her vote. Many male legal scholars agreed with Gougar that Leach’s case set a precedent that granted women a constitutional pathway to the vote. But women’s voting was a sphere too far in 1897. Ability to earn a living as one chooses is a right, said the Indiana Supreme Court. Voting is a privilege. Privileges are conferred, said the court, and nobody had conferred that privilege to women in Indiana.

Fast forward 125 years from Indiana’s first female lawyer to the elections of 2018, nearly 100 years after Hoosier women got the right to vote. Monroe County became one of the few Indiana counties to have a female majority in their circuit court bench, with eight of the nine judges being female. Monroe County elected its first female chief prosecutor, and, in 2019, Bloomington attorney Betsy Greene was voted by her peers as the best lawyer in Indiana.

Owen County has the first all-female bench in the Indiana county court system, with the Hon. Lori Quillen and Hon. Kelsey Hanlon. Lawrence County’s head judge is a woman; the Hon. Andrea McCord has held this seat since 2008. Nearly forty years after the first woman was appointed as the first state appellate court judge (the second-highest level in the state court system), Indiana Supreme Court Justice Loretta Rush became the most powerful judge in the state, the first time that position has been held by a woman.

The future is female, and both women lawyers and women voters — and, one could argue, all Americans — owe a debt to Antoinette Leach.

“The right to woman to earn an honest living whether it be from necessity or ambition, is an inalienable right to her as an American citizen, as a human being, and the rough justice of the world has discovered what her abilities are,” she told women in the June 4, 1902 edition of the Indianapolis News. Women “must practice as a man does,” in law and other areas of their lives. “One must be industrious, honest, faithful and loyal, work like a horse, and live like a hermit.”

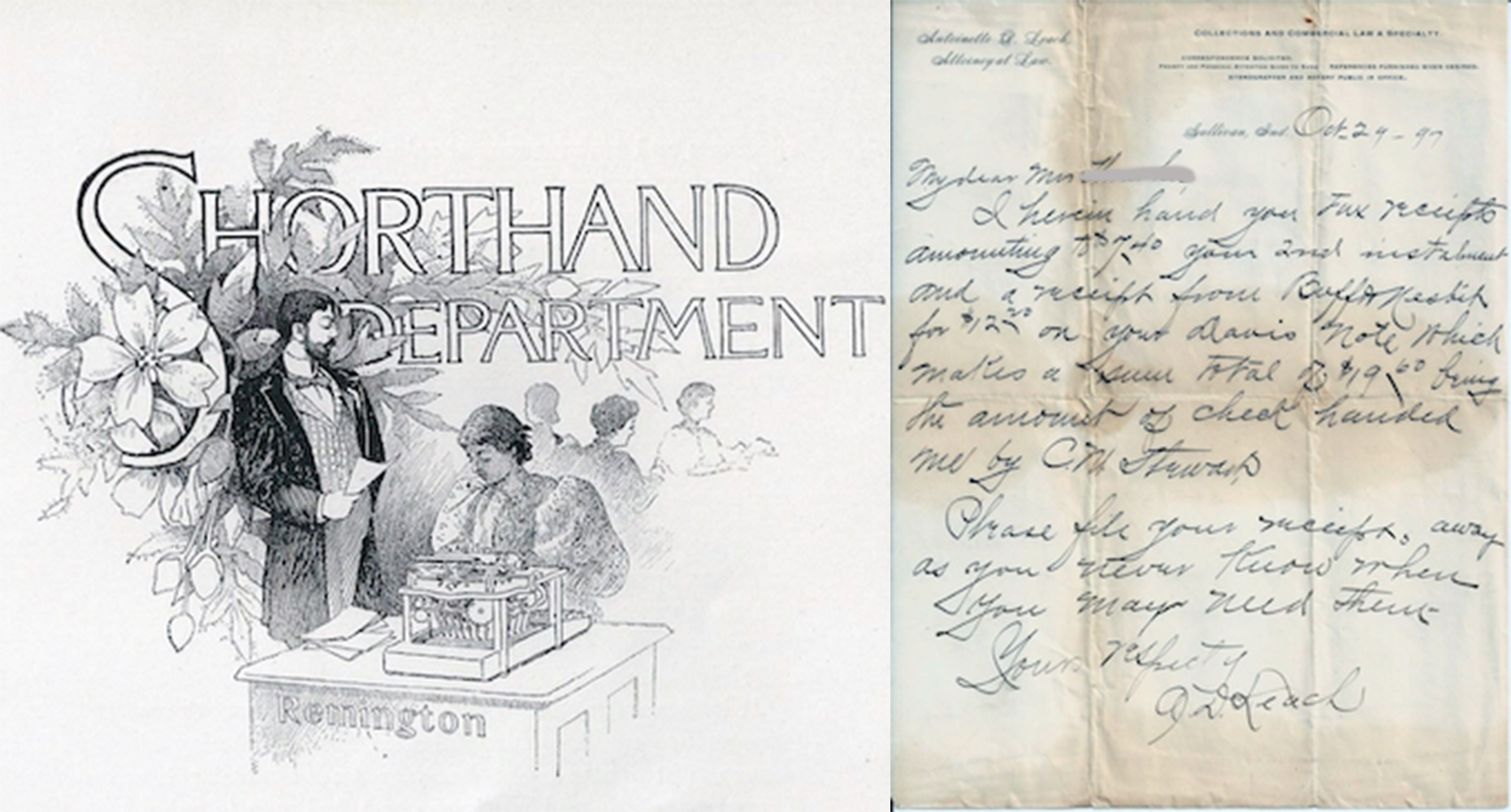

(left) From a pamphlet advertising a business college that Leach started after she became a lawyer. (right) A client letter Leach wrote on October 29, 1897: “I herein hand you Tax receipts amounting to $7.40. … Please file your receipts away as you never know when you may need them.” | Images courtesy of the Sullivan County Historical Society

Despite her tough talk, Leach was not a hermit. She published a monthly magazine called Woman Citizen, started local suffrage associations, chaired the otherwise-all-male Progressive Party in Sullivan, and attended every statewide suffrage meeting. She was in the first Indiana delegation to attend the annual convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), held in Louisville, Kentucky, in October 1912. The president of Indiana’s delegation, Anna Dunn Nowland, noted Leach was spending “all her time on suffrage.”

In 1911, Leach presented a bill to the Indiana legislature giving women the right to vote, according to Nowland’s address to the NAWSA.

“Mrs. Leach, author of the bill, the officers of the Suffrage Association, and many friends, zealously watched the bill in its progress,” said Nowland to the convention. “[Leach’s bill] passed the committee by a unanimous vote, passed the second reading before the House without amendment, but when brought forward for the third reading, it was laid on the table, because as the Hon. Speaker stated, ‘There is no time to consider such foolish questions.’”

The 1911 Speaker of the House, despite his stagy disdain, was not dismissing an unheard-of idea. It was common to consider women’s suffrage and table it; Indiana’s all-male legislature considered female suffrage ten times in the 20 years between 1897 and 1917. A bill allowing women to vote in municipal, school, and special elections passed in 1917. An Indianapolis businessman sued, arguing taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay for extra poll workers or the special polling stations for women that this law required. The Indiana Supreme Court agreed and killed the bill by February 1918. Indiana women wouldn’t get the vote until after the country ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.

After ridicule at Indiana’s statehouse in 1911, Leach must have enjoyed the energy and uplift of the NAWSA convention with likeminded women from across the country, which included Jane Addams, Emmaline Pankhurst, Anna Howard Shaw, Alice Paul, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Dorothy Dix, and Katherine Hepburn’s mother, Katherine Houghton Hepburn. At the convention, activists taught political tactics, “interesting the uninterested,” and raising money. They discussed initiatives on rights for divorced women to their children, pay equity, the abolition of child labor, and “sex hygiene,” among other issues. The women topped off this week of getting stuff done by going to Mammoth Cave.

Origins of the ‘woman militant’

Leach was born Antoinette Dakin in Wooster, Ohio, in 1859. Her father died when she was only a few months old, and her mother married an Owen County man named Brighton who moved the family to Gosport, Indiana, when she was young. The Brighton family is still prominent in Gosport, according to Judge Quillen, who is an Owen County native and had a Brighton descendant as her sixth-grade teacher.

“I imagine she had to be fairly independent at a young age,” says Tom Frew of the Sullivan County Historical Society. Leach was also ambitious, “born that way, I guess,” says Frew. She attended a private academy, and after graduation at 16, she taught for four years until she went to college at Wesleyan University in Dayton, Ohio. There she met her husband, George Leach.

According to Frew, the Leaches had an unusual relationship for the time. Antoinette and her husband agreed that she could pursue any professional career she chose. In 1884, after the birth of her second and last child, she moved to Knoxville, leaving the children with her mother, to get a law degree from the University of Tennessee, only the fifth woman in the United States to get a law degree, according to a Baltimore Evening Sun story on Leach, published January 31, 1911. Back in Sullivan, Leach continued her studies at Detroit’s Sprague Correspondence College of Law and worked as a law clerk for local attorney John Bays, who would serve as her lawyer before the Indiana Supreme Court in her petition to become an attorney. Antoinette was also the court reporter for Judge John Briggs, the Greene-Sullivan circuit court judge who denied her initial petition for bar admission.

In 1884, when selling alcohol was still legal in Sullivan County, Antoinette and her husband, George, built the Arcade Saloon. Later, after the county became dry, George ran several illegal bars called “blind tigers” and was arrested a few times. He had to declare bankruptcy, and Antoinette’s successful law practice saved the family finances. The Arcade Saloon now houses the Sullivan County Historical Society. | Photo by Diane Walker

Frew says the Sullivan County male attorneys respected her work and submitted letters supporting her admission to the bar. After her admission, he says, she had no problem getting clients, in part because Sullivan County’s coal mines had started to produce. Shortly after, 34 towns sprang up in Sullivan County, some of them no more than a saloon/dance hall. Such booms produced criminal clients for Antoinette, according to Frew, but her law office letterhead shows that she specialized in “Commercial Law and Collections,” a shrewd specialty in a burgeoning town. Antoinette also started a co-ed business college that taught bookkeeping, shorthand, typing, banking, and “methods of office practice,” among other things.

George Leach ran several illegal bars called “blind tigers” in Sullivan County, which was a dry county from the late 1880s into the early 1900s. Patrons asked to see a blind tiger, Frew says, and were led into a room where there was liquor under a drawing of a tiger. “During working hours, he was doing his own thing, and she would do hers, and neither would interfere,” laughs Frew. “George Leach got arrested quite a few times. She was kind of working with the law, and he was working outside the law.”

In 1884, when serving alcohol was still legal in Sullivan County, George and Antoinette built the Arcade Saloon, which now houses the Sullivan County Historical Society. Antoinette’s successful law practice saved the family finances, because George had to declare bankruptcy after a crackdown on blind tigers.

George and Antoinette loved each other devotedly, according to Frew. George may have known he had a star on his hands, as newspapers started covering the exploits of his ambitious and unconventional wife. National news services in 1896 picked up Antoinette’s serving as the first female delegate at a statewide political convention east of the Mississippi. Her male colleagues concealed her gender by registering her as “A. Leach” and providing a male alternate in case she was booted. Newspapers all over the country recorded that Leach put up with the smoky back rooms and voted as a Silverite, a movement which favored a free silver monetary policy as opposed to the gold standard — a hot-button topic of the times.

Leach was passionate about the law and used it as a template for her life. In the 1902 Indianapolis News story in which she encouraged women to practice like a man, she wrote, “I do not want to be understood as encouraging the study of law … to the detriment of marriage, for I consider marriage and motherhood the loftiest ambitions of a woman’s life — but there is so much waste of time in most women’s lives that might be turned to better use, and that is why I encourage the study of law, for no other study will bring a woman in such harmony with her husband, home, and heaven as the law.”

Leach presented quite radical ideas for the time in this article. She went on to write that when a woman married, she should “take a writ of garnishment on your husband’s household, and if at any time he replevins or moves to quash your writ, you will be able to negotiate a settlement, and in five hundred years from now the world will be better for your having lived in it.” A “writ of garnishment” is an old-fashioned term for a legal order for payment, so she’s suggesting metaphorically that women start their marriages from a position of power, economic and otherwise, and if a husband disagrees, or “moves to quash” that assertion of power, married women can still reach equality.

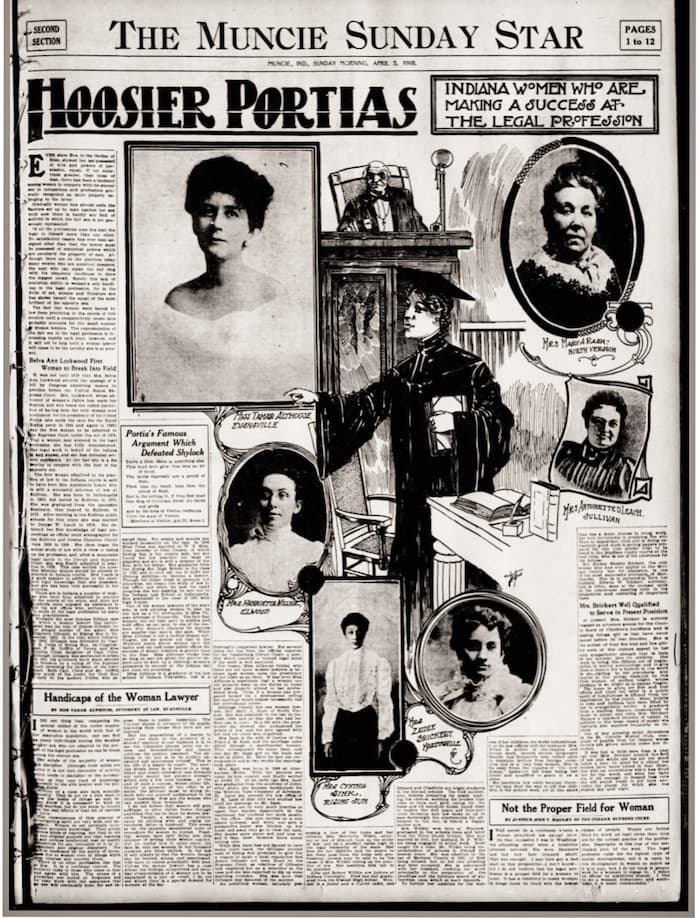

A photo of Leach (far right column, bottom) appeared on the front page of ‘The Muncie Sunday Star’ on April 5, 1908. The feature was titled “Hoosier Portias: Indiana Women Who Are Making a Success at the Legal Profession.” One of the three articles, written by Indiana Supreme Court Justice John V. Hadley, was headlined “Not the Proper Field for Woman.”

Though her ideas were published, not everyone was comfortable with women’s equality and exercise of power in marriage, at the ballot box or in the courtroom. Leach’s photo appeared on a front-page feature in The Muncie Sunday Star on April 5, 1908, which was completely devoted to “Hoosier Portias.” One of the three articles in this feature was written by a “Miss Tamar Althouse, Attorney at Law in Evansville.” Unlike Leach, Althouse sold out her sex, writing, “The minds of the majority of women lack discipline.” Indiana Supreme Court Justice John V. Hadley wrote the second article about Indiana’s female lawyers, headlined, “Not the Proper Field for Woman.” Perhaps because Leach’s opinions did not mesh with the rest of the front-page articles, the final article, written by a staff reporter, did not quote Leach but noted blandly, “Mrs. Leach is a good speaker in addition to the excellent legal knowledge that she possesses and she has been very successful in her practice.”

Newspapers in Baltimore and Tacoma, Washington, reported on her unsuccessful candidacy for the Indiana legislature in 1910. The Indianapolis Star wrote in November 1912 that as the elected chairman of the Progressive Party she was the first in the state to send in election results. In its February 11, 1911 article, the Fairmount News headlined, “Look for Fight in the House,” as Leach spoke for women’s voting rights, leading a gathering of 200 women in the Indiana House. The South Bend Tribune reported on the same legislative session, characterizing Leach as “the woman militant” at whom a “good many representatives laughed outright, to the discomfiture of the more gallant members and the chagrin of the skirted enthusiasts.”

Leach was apparently not too chagrinned. The Brazil (Indiana) Daily Times wrote in October 1914 that she and Nowland were posting women watchers at every voting place in Indiana to persuade each voter to pass female suffrage.

Leach’s Legacy

George Leach died in December 1919, and in failing health herself at 60, Antoinette went to live with her daughter in Binghamton, New York. In a savage irony, Antoinette wasn’t able to vote even after the 19th Amendment was enacted in 1920 because she hadn’t lived in New York long enough to establish residency. She did, though, watch her daughter go to the polls in 1920, according to a 1960 feature article about Leach in the Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin.

“I’m sure it killed her,” said Leach’s granddaughter, Georgia Mathis, of Antoinette’s not being able to vote. “Mom [Leach’s daughter] hadn’t lifted a finger for suffrage, but she’d lived in New York long enough to vote.” Antoinette died in June 1922, before the next presidential election. Mathis said that she herself voted every year. “Grandma would turn over in her grave if I didn’t.”

If voting is powerful for women, so is the practice of law. One hundred and twenty-six years after Leach began her practice as a lawyer and her career as a political activist, the power and presence of women lawyers have increased exponentially, mostly in the past thirty years.

Judge Quillen echoes Leach’s legacy when she says, “You’ve got to have enough discipline and determination to know that even if someone says no, that you’re entitled to it, you’re worthy of it, and if you work hard enough you will get it.”

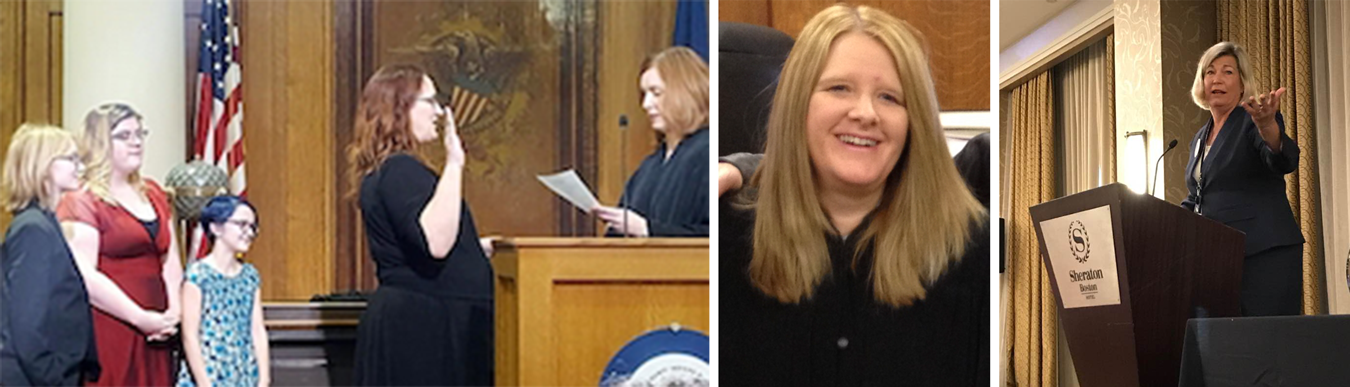

Quillen graduated from law school in 1989 in a class that was 35- to 40-percent women. Betsy Greene, a founding partner in Greene and Schultz Trial Lawyers, says her graduating law class in 1982 was about one-third female. In 2016, The New York Times reported that women made up the majority of U.S. law students for the first time.

Since Greene and Quillen began their careers, discrimination has waned but was poisonous and obvious during the start of their practice. Greene relates a story in which an older male lawyer was on the opposite side of her in a jury trial. Greene says, “I was 5’11, and I wore heels, and I was a lot taller than him. ‘Little lady,’ he would call me, ‘Le-e-etle lady.’ Finally I told him, if you call me that in front of the jury, I’m going to call you ‘old man.’ And then he quit.”

In 1989, Quillen did her “character and fitness interview,” an ethics interview required before admission to Indiana’s bar, with an Owen County attorney. “He wanted to make it very clear that we didn’t need any women attorneys in this county to practice,” she says. “And he wanted to make sure I wasn’t coming back here.” She laughs: “I think he would be quite upset to know that I’m now serving as a judge of the Owen Circuit Court.”

Nevertheless, women attorneys have found their way, as Antoinette Leach suggested they might when she wrote about “the rough justice of the world” revealing women’s talents. Greene thinks there are even some things women lawyers may do better than men. “Listening is a huge skill when you’re doing cross or direct [examination in the courtroom], and I think listening is something women do pretty well.” Before she became a lawyer, Greene waited tables, a profession that’s almost 70 percent female, according to public federal data. Presenting evidence to a jury is like waiting on a table of six, she says. “You’ve got to figure out what they want and give it to them.”

Judge Catherine Stafford, one of the female judges elected to the Monroe courts in 2018, had her own law practice before moving to the bench. She believes women can be more diplomatic in redirecting clients, even in an emotional area like family law.

“Any human will get defensive when being told they’ve done something wrong, especially when it’s about their children or their family. And when they have in fact been wronged by the other spouse but they have to be nice, that’s a very difficult expectation,” she says. “[Clients] would say, ‘How many times do I have to turn the other cheek?’ and I would say, ‘Forever, for always. You just have to keep turning it because your kids are worth it.’ And when you say it like that, they get it.”

(left photo) Judge Catherine Stafford (center), being sworn in by Judge Holly M. Harvey on January 1 at the Monroe County Courthouse with her son, daughter, and step-daughter watching. (center photo) Judge Lori Quillen of the Owen County Circuit Court. (right photo) Attorney Betsy Greene in 2017, accepting the Marie Lambert Award from the American Association for Justice Women’s Trial Lawyer Caucus in Washington, D.C. | Courtesy photos

Has equality been attained?

Women have arrived as lawyers in the sense that no one is surprised to walk into a courtroom with all female lawyers and a female judge, says Stafford. But Greene, Quillen, and Stafford agree that women lawyers have not completely arrived.

All mentioned that women lawyers are not always paid as much as men. Quillen says this affects the non-lawyer court reporters (some of whom are men, but the majority of whom are women) who do highly skilled work and administrate the judge’s court but are equally slighted in pay because it’s considered a woman’s job.

Greene says there are fewer opportunities for women to become corporate lawyers and CEOs, and women may be risk averse in starting law firms because they need a paycheck and may not get paid for their work until after a trial or settlement. Stafford notes that easily accessible and affordable child care is rare, and this can be a struggle particularly for women.

Progress for both men and women means having women and their concerns visible in the legal profession, from Leach to the present, according to Greene and both judges. Greene teaches her trial skills to male and female attorneys every year, alongside her own mentor, retired Morgan County Judge Jane Craney. Stafford, who was first sworn in as an attorney in Minnesota, tells an anecdote about then-Chief Justice Kathleen Blatz of the Minnesota Supreme Court, who emphasized family to all attorneys.

“[Chief Justice Blatz] was a rock star,” says Stafford. “All of us young female attorneys wanted to be her. She was cool, she was smart, she was organized.” Blatz didn’t appear at the ceremony, but an associate read a note from her that stuck with Stafford: “It said, ‘My son has a 102-degree fever, and so, as a mom, I’m staying home with him today. If it is all right for the chief justice of the state supreme court to stay home with her son when he’s sick, it is okay for every one of you to stay home with your kids when they are sick, and you should do so.’”

“That making it okay, and that making it a norm, to be both a parent and a lawyer, to be a person and a lawyer, that has stuck with me my whole career,” says Stafford. “She just gave us such a huge blessing by saying that.”

Stafford says she will be thrilled if her 9-year-old daughter or 12-year-old son go to law school. Quillen’s daughter is in her first year of law school, and Greene’s elder daughter was just accepted to law school. All of them have benefited from Leach’s legacy as the first female attorney in Indiana, but Quillen says Hoosier women also remember her legacy as a fighter for women’s rights.

“It’s not been that long when you look back at when we’ve had those votes,” Quillen says. “Certainly we need to get out and do that more, fight for what we believe in.”

[Update: On May 20, 2019, Judge Andrea McCord, mentioned above as the presiding judge in Lawrence County, was sworn in to the U.S. Indiana Bankruptcy Court, Southern District of Indiana. She is only the second female bankruptcy court judge in Indiana. The first, Judge Robyn Moberly, won 2018’s Antoinette Dakin Leach award.]