[Editor’s note: Monroe County Public Library Community Librarian Christine Friesel contributed to this article by providing dates and key information from city records regarding the life of Edwin Fulwider and his family.]

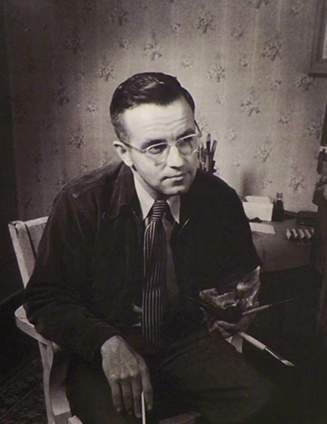

Fulwider was born in Bloomington in 1913 and grew up to be an esteemed artist. However, he’s been largely forgotten in his hometown. | Photo courtesy of Covington Fine Arts Gallery

At the Monroe County History Center on 6th and Lincoln streets, there is a comb-bound, photocopied manuscript of a peculiar memoir by an artist named Edwin Fulwider. A search for this book online or through the international library catalog WorldCat, however, yields no results, and it seems not to exist at all. The text was published by a now-defunct vanity press out of Idaho in 1989, ironically named Keepsake Press. In 2017, while compiling research for the Monroe County Timeline, Christine Friesel, the community librarian at the Monroe County Public Library (MCPL), accidentally discovered the artwork of Fulwider. As a librarian for MCPL’s Indiana Room, Friesel says she often has chance interactions with little-known pieces of local history, but Fulwider was a particular surprise: “I was just amazed that I had never seen his work despite living here 25 years.”

Why it seems so few residents of Bloomington (myself included, until meeting Friesel) are familiar with Edwin Fulwider’s work is what makes the memoir a peculiar object — which isn’t necessarily to say uncommon. Living in Bloomington, one often makes contact with local ephemera — artwork, tapes, zines, books — that may be important, poignant, and beautiful for a time, before disappearing. It can be, at once, odd and totally unremarkable to see an object or a person flirting so closely with obsolescence. Though perhaps, as Friesel points out, it is striking when a person who became and remains quite esteemed in the art world is largely forgotten by his hometown.

Edwin Fulwider was born in 1913 and grew up in what is now Bloomington’s Prospect Hill neighborhood. After studying at the John Herron School of Art in Indianapolis, Fulwider taught at the Cornish School of Allied Arts in Seattle. He worked alongside many important modern-regionalist painters of the time, including Thomas Hart Benton, while Benton was painting The Indiana Murals for the 1933 Chicago’s World Fair, and Henrik Mayer, Fulwider’s college mentor. In 1939, his painting Dead Head showed at the San Francisco World’s Fair, and, shortly after, the work was published in Life Magazine. He also worked as an instructor, professor, and eventually chairman of the Department of Art at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Fulwider’s memoir, which was inspired after an impromptu visit to his hometown in 1986, explores his adolescence in Bloomington during the interwar period nearly one hundred years ago.

Fulwider grew up in a house on the corner lot of West 3rd and South Jackson streets. It is on a hill, which was perfect for Fulwider’s mother to keep tabs on everyone in the area. | Limestone Post

A young Fulwider

Edwin Fulwider grew up with his two brothers, Bill and Lawrence, in a house on the southwest corner of West 3rd and South Jackson streets. His father owned and operated the Fulwider Lumber Company, which once stretched a full city block south of 3rd Street between South Madison Street and the Monon Railroad (the block was most recently home to High Speed Tire). His mother was a homemaker with whom Edwin shared a fraught relationship.

Fulwider spends much of his childhood exploring his father’s lumberyard and mills. His memories of the company provide epoch-marking details of a booming late-industrial era — giant steam boilers, horse-drawn carts, a large workforce of skilled craftsmen — just prior to the Great Depression.

Their house (525 W. 3rd St.), perched on a hill, overlooked the lumberyard and several familiar blocks westward and to the north. “Being on a corner lot had many advantages,” writes Fulwider. “Third street jogged about a hundred feet south on Jackson Street before resuming its western destiny…. This was a marvelous feature for mother because her kitchen window looked right out on West Third and she could see for blocks, thus commanding a tremendous power over the activities of Third Street West and all its peculiarities.” Fulwider’s descriptions of the house, a “fortress” as he calls it, with its “commanding views,” are apt for a young man growing up during a period of profound war. He would watch the approach of summer storms and followed along during a string of arsons when “every night someone’s house burned.”

At a young age, Fulwider fostered interests in art, architecture, travel, and trains — unusual pastimes for a boy at the time. He became particularly enamored with the rail system, memorizing the trains’ schedules and timing their interval stops as they crossed through town, especially while he was bored in class.

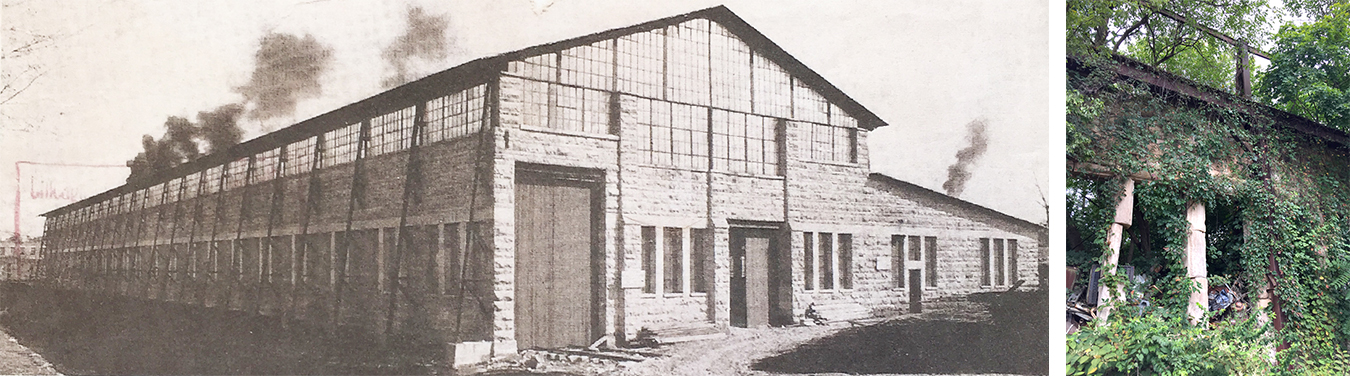

There’s a chapter dedicated to a shopping trip to Indianapolis he took with his mother and grandmother on a passenger train, as well as a detailed depiction of the scenery along the way. He also spent much of his time drafting and building furniture for himself in the family lumber mill. Recognizing this early faculty, Fulwider’s father helped Edwin earn a summer apprenticeship with the drafting office at the Shawnee Stone Company, a massive limestone mill between West 7th and 11th streets on North Rogers. (Shawnee eventually merged with Central Oolitic Stone Company; the location is currently home to Bloomington Iron & Metal, where remnants of the mill can still be seen along the B-Line Trail.) That summer of 1930, Fulwider says the company had three important contracts: The Gulf Oil Building in Pittsburg, The Bell Telephone Building in Nashville, Tennessee, and the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

Molly Carr

[Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from Fulwider’s chapter on his teacher Molly Carr and his third grade classroom, which was located at Old Central School, south of the square on College Avenue, where Courtyard by Marriott stands now. The excerpt shows Fulwider’s love of architecture, art, and trains and also the details and care that Bloomington’s builders put into their work at the time. Grammar and spelling have not been corrected.]

Old Central School was located just south of where the Monroe Convention Center stands today. The back of the school overlooked the Monon railroad, now the B-Line Trail. Pictured here in 1907, the school was built in 1873 and was torn down to build a parking lot in the 1950s. | Photo courtesy of the IU Archives

Central was an example of pure Victorian Architecture of the finest kind, with all the features of a Mansard roof high above the three stories, with those wonderful ornate dormers much like on the Tinker Mansion, and a classic tower with a Mansard top which commanded a view of all Monroe County. This colossus … backed up to the Monon Railroad and was directly across the tracks from father’s lumber yard. … I have used it thousands of times in my paintings. It can be seen sticking up in backgrounds in almost all of my victorian towns and skylines. My appreciation of Architecture, even before I knew it was “Architecture,” and my interest in the railroad so far transcended anything I could possibly get out of school that it made me a misfit.

Molly [Carr] reined supreme in a room on the back side, second floor, affording a clear and beautiful view of the Monon and all the great trains that chugged up the one percent grade through town. Oh, what magnificent sights, those trains with their 2-8-4 locomotives fresh from Baldwin and a heroic Casey Jones at the throttle with his arm resting on the window sill, a foot proped up on the boiler head and a cigarette in his mouth. This was my downfall.

Molly went home and told my mother that Edwin would never do well. “All he does is look out the window at the trains.” “He pays no attention to his reading and arithmetic, he is nothing but a dreamer and loafer.” … Little did they suspect all my minute understanding of the inner workings of the railroad, my extensive knowledge of the scheduling of trains, assignment of crews, and all the important functions involved in the operations of the Monon. I really could predict with almost perfect accuracy the engineers and firemen that would be on each individual train. I knew how they alternated days due to the length of their runs. My expertise in such matters was completely wasted on my mother and Molly and everyone else. … I was occupied with worthwhile projects like plans for big bridges for railroads, or tunnels, nothing small. I was sure I would be a great Civil Engineer and go west and build that big railroad to the sky, or find a new low level pass through the Rockies, nothing so stupid as that damned arithmetic we had in third grade. Hell. I knew all about that long ago at the mill. …

(left) Fulwider worked in the drafting office of Shawnee Stone Company (also known as Central Oolitic Stone Company), located between West 7th and 11th streets on North Rogers, in the summer of 1930. | Photo courtesy of Bloomington Iron & Metal; (right) Remnants of the stone mill can still be seen today. | Limestone Post

1920s Bloomington

Though Fulwider forged his own niche in Bloomington, he describes himself as a lonely outlier in a city he often found dull and unsophisticated. In one particular chapter, “The Band Concert,” Fulwider remembers parking downtown every Saturday evening with his family to watch a large brass band play on the courthouse lawn. He ridicules the bandleader for having no sense of aesthetics or knowledge of music history.

![Edwin Fulwider's 1931 senior photo in the Bloomington High School Gothic Yearbook. Monroe County Public Library Community Librarian Christine Friesel says, "He graduated with other famous locals, including Ross Lockridge, Jr., Edwin Farmer [of the <a href="https://www.facebook.com/FarmerHouseMuseum/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Farmer House Museum</a>], and Fred Easton [a St. Charles Catholic priest]. Many others in that class were pillars of the local small business," such as the Sare family and Canada family. | Public domain](https://www.limestonepostmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/1931-Bloomington-High-School-Gothic-Fulwider-cropped.jpg)

Edwin Fulwider’s 1931 senior photo in the Bloomington High School Gothic Yearbook. Monroe County Public Library Community Librarian Christine Friesel says, “He graduated with other famous locals, including Ross Lockridge, Jr., Edwin Farmer [of the Farmer House Museum], and Fred Easton [a St. Charles Catholic priest]. Many others in that class were pillars of the local small business,” such as the Sare family and Canada family. | Public domain

Even as a young boy, Fulwider views the local concert as a pitiful and second-rate affair. He remembers how the position of the lights on the band’s sheet music would blind his father, forcing him to listen with his eyes closed and often fall asleep, once nodding off onto the car horn during a tune. Regardless, Fulwider includes sparkling imagery of the concerts:

However, the band had a unique place in the social structure of the town. The weekly free concert on the Courthouse lawn drew record crowds. Unlike many towns, ours had no bandstand but rather a high bank on the south side of the Courthouse yard, with a bank of steps leading down to the street which provided an ideal place for the band to perform. This arrangement put the band several steps above the audience who occupied the sidewalk or street, in parked cars or folding chairs provided by the people themselves, or in some cases by the local mortician.

In 1922, Fulwider’s parents sold their family home on 3rd and Jackson for a house on the corner of East 7th and North Lincoln streets. He believes the move, underpinned by his mother’s desire to move up in society, was to blame for the sudden erosion of his family’s happiness. He claims they could never adjust to the new affluent neighborhood where “eastside heathens” were. Growing up on the west side, predominantly occupied by families of manufacturing workers, Fulwider had long grown skeptical of “University people.” This opinion emerges in memories of his grandmother’s boarding house, which provided full food and laundry service to its 25 boarders of IU graduate students, faculty, and the eccentrically unwed. Fulwider praises his grandmother’s staff and criticizes the tenants’ false pride and “intellectual snobbery.” Fulwider would also blame the university’s “hostile environment” for the disappearance and death of a young student, Esther Beck. Beck, who was the daughter of a university professor in a prominent Bloomington family, was found frozen to death in a nearby pasture during a town search. Fulwider writes:

In our small college town there was a constant bickering between the town and gown. The citizens of the town were at odds with the intellectuals at the university. The townspeople did not understand professors who lived in the clouds away from reality, living off the taxpayers and for what good? And anyway, the college was getting too big, nearly two thousand students. Anyone knows it is impossible to educate that many people at one time. The whole thing should be closed down and the land turned back to tillage. From this limited atmosphere, Esther Beck disappeared.

Fulwider’s introspection into this familiar tension between “town and gown” is made rich by his many experiences living across a broad gamut of Bloomington’s neighborhoods and their relative socio-economic classes: the west-side white working-class neighborhoods as a child, the east side’s university population and upper-middle crust as a teenager, and the impoverished northwest region as a young adult. After graduating from the Herron School of Art in Indianapolis and touring Europe on a travel scholarship, Fulwider returned to Bloomington with his fiancé, Ellen Kathryn “Katy” Ham. For the first sweltering summer, they lived in the attic of his grandfather’s old home on 3rd and Madison, which had been left to his Aunt Ida, a painter whom Fulwider greatly admired. At the time, he and Katy were unemployed and looking for work. According to the 1936-1937 city directory, Edwin and Katy moved into Edwin’s former home at 302 E. 7th Street where his mother still lived. (Edwin’s mother and father separated, though remained married all their lives. According to the 1940 census, Edwin’s mother is renting a room in the 7th Street house alone, and Edwin’s father has moved in with his sister Ida; however, it is unclear if Edwin’s father has already moved out by the time Edwin and Katy return in 1936.)

(from left) The Fulwider family moved from their house in what is now Prospect Hill to this house at East 7th and North Lincoln streets, in what Fulwider considered the more affluent side of town where professors “lived in the clouds away from reality.” As an adult in the late 1930s, Fulwider returned to Bloomington and lived in a house on the “wrong side of the tracks,” in what is now Maple Heights. | Limestone Post, center photo courtesy of the Monroe County History Center

In the spring of 1937, Katy became pregnant with their first child. Fulwider found employment in Indianapolis and, according to his memoir, began renting a studio at the corner of 6th and Walnut (above what is now the restaurant Samira), before losing his job and moving in with his mother directly after the birth of their child. City records indicate that Fulwider began renting the house on West 15th Street in 1938 (though he says 1937 in the memoir), and that he and Katy were still living with his mother at 302 E. 7th St. during Katy’s pregnancy and the birth. He seemed to savor his independence, as he quickly glosses over living with his mother, and remarking once that he took pride in renting the house on West 15th Street, which was notoriously “on the wrong side of the tracks,” both literally and figuratively. The memoir ends suddenly in the close of that year: On Sunday, December 26, the day after Christmas, Katy had their first child, Edwin Jr., in a hospital in Indianapolis. On Monday, the day after their son’s birth, Edwin writes that he was laid off from work.

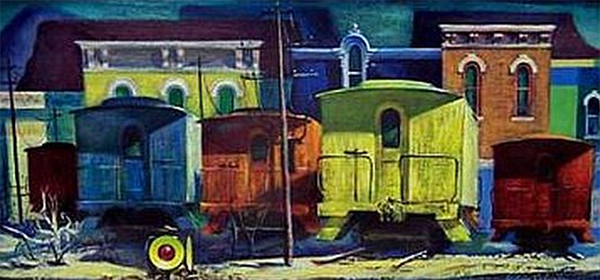

Trains and familiar Bloomington architecture frequented Fulwider’s work, such as this painting, called ‘Sidelined #399.’ | Photo courtesy of Covington Fine Art Gallery

No matter the tumultuous end of Edwin Fulwider’s life in Bloomington, we can gather from his paintings that his head remained “full of trains.” The artwork he would go on to make articulates railroads, train stations, and city structures of the American Midwest and Mid-Atlantic, in the style of his fellow modern-regionalist artists: abstracted imagery, bright blocks and smears of primary colors, and a certain fascination with subjects of modern technology and American primitivism.

In a rare visit, Fulwider briefly returned to Bloomington in 1986 and writes that he is satisfied to see his family’s former homes still relatively unchanged and in good repair, and is aggrieved by the absence of the great lumberyard and Shawnee Stone Company. He writes in the foreword: “This is the subject of this narrative, a revisit into a past that can never happen again. … The world has changed, and this way of life is gone forever. It is recorded here more as a curiosity than anything else, a record of an era by a participant, one of the few left to tell the story.” In the succeeding chapters, however, it becomes clear that this memoir is more than just “a record by a participant.” Fulwider’s historicizing and objective posturing often folds under emotional duress: He becomes suddenly angry and embittered toward the people from his past, as if, in remembering, he slips back into the figure of this young and picaresque boy again — too agitated to be soothed by his mother, still too agitated to be soothed by time. This effect, however startling, tends to make Fulwider’s memories feel all the more immediate and alive.

Fulwider’s artwork is widely accessible, housed across numerous museums and private collections, as well as viewable online. This document of his (and our) past, and its many reflections in his lasting artwork, together form a rich landscape of local art, life, and history to be explored as a community. For those of us, like myself, who lived in Bloomington many years then moved away, perhaps for just a time, Fulwider’s expression of just how complex it can feel to go home — all at once arousing and boring, illuminating and confusing, painful and effortless — is not easy to forget.

The Trains

[Editor’s note: The following is from Edwin Fulwider’s book, A Memoir, published in 1986. This chapter is on Bloomington trains, especially the Illinois Central [I C] Railroad that Fulwider would sometimes take to Indianapolis to go shopping with his mother and grandmother. He tells of the various stops and sights along the way, as they hop on at the bridge near North 12th Street between College and Walnut and head north through Unionville, Helmsburg, and Bargersville. Fulwider also mentions the Monon Railroad, which had a station on the same block that WonderLab Science Museum is now. Grammar and spelling have not been edited. He begins with his “pilgrimage” to Bloomington in the 1980s.]

This photo looking north over Bloomington from the roof of Bloomington High School was taken in 1915, just two years after Edwin Fulwider was born. The street at the bottom is 2nd Street between College and Walnut. | Photo courtesy of IU Archives

The next stop on my pilgrimage was the I C Depot, or rather I should say the site of the Depot, the main structure had been torn down. However, the freight station was still standing and was being used as a “station” by the train crews who had to have someplace for a phone connecting them with the dispatcher, wherever he was. This structure was located on what had been almost the north edge of town, about three blocks nearer than Kenwood, my aunts home. It was between Walnut and College Avenues, very high above the streets with bridges over both. The station perched on a high earthfill made it a dominating structure in the north end of town. Actually, Bloomington is a hilly city and the height of the station was not as noticeable as it might otherwise have been. Unlike the Monon Railroad, this station was quite a ways from downtown. It was as though it had been an afterthought. The I C was late in coming to Bloomington, which necessitated its almost suburban location.

Our little I C station was perfection in the art of Railroad Architecture. Never had man so eloquently expressed beauty and function-following-form than in this little jewel. It was beautifully proportioned with balance in the span and design of the corbels supporting the projected roof which extended shelter almost to the tracks. This was repeated in the covered passageway between the passenger depot and the freight station, an integral part of any depot complex. An ornate ramp and cover were provided from the street and parking lot to the elevated depot. This was all built before the automobile, when parking was no problem except for a few horse drawn cabs and hacks that met the trains each day to take passengers to the various hotels or restaurants. Families met their own passengers with their own rigs, or mostly just walked, a common practice in those days.

In the station was the Railway Express office, a unique method of shipping packages too big for the U.S. Mail Parcel Post, but too small for freight. The Express service was fast, just like passenger train service, and very popular. It succumbed later with the passenger train business, and was a tremendous loss of service to mankind.

Our depots were great meccas at train time. Anyone free at the moment could go to the station to see who arrived or departed, what the drummers were selling these days, and also the latest news from the big city by word of mouth from the train crew, or the newspapers that came in from the capitol city, copies of which were rushed to the local newspapers for copying into the evening edition.

Edwin watched the I C Railroad from his classroom windows at the McCalla School near East 10th Street and North Indiana Avenue. | Photo by Nyttend

Our other railroad went north and south through town and was called the MONON. … I watched the Monon from the big victorian windows of Central School, and later when we moved across town I watched the I C from the large plain windows of McCalla School, where I was regarded as just as much an idler as I had been at old Central.

I went to McCalla School each morning in anticipation of about nine o’clock when the little “Accommodation” train left the I C Station to go to Indianapolis. My interest in small passenger trains began with this little consist of a Pacific locomotive — a real high wheeler, a baggage car, a combination car whose passenger compartments were divided between a smoker and non-smoker sections, sometimes another passenger car, and even a second one if there was a ball game at the college. This little engine puffed itself across my view as it left town trailing its coaches and a plume of steam and smoke. In man’s inevitable progress from premordial ooze to the so called civilization of today, there has probably never been anything as fascinating as the little local or accommodation train that made all the stops, hauled all sorts of local freight from milk cans to mail sacks. Sometimes even a long box, a special Railway Express shipment with high priority. So it was, the day had begun auspiciously with these profound observations, now I had to buckel down for a few minutes of study to await the local freight from the east, torn all the while by having to watch both the window and old Ben Johnson who by this time had his measure of me. …

Young Edwin’s trips to Indianapolis with his mother and grandmother included a ride over the Shuffle Creek trestle in Unionville. | Photo by Nyttend

We often rode the little morning train to Indianapolis. Mother and Grandma Robertson would go to the city to shop, which usually meant they were taking the day off. I would get mother to write me an excuse so I could go with them and we would leave around nine o’clock on the accommodation train. As I passed near the school, I would walk to the back of the train and lean out the back door and thumb my nose at old Ben Johnson. To a boy growing up with trains in his head, this was a trip of a lifetime. After leaving town it was all new, the railroad unlike the roads, cut right across fields and streams, through barnyards and forests, regardless of property lines. It always took the shortest route even if people had to move over a little bit to accommodate. Unionville was the trains first stop, if it was flagged. If there were no passengers or express the train proceeded. We usually sailed right through and then came the big highlight … we would soon go through the only tunnel on the railroad. I always looked forward to this. I would be standing in the rear vestibule, with only a small folding screen to keep me from falling out the rear door. This screen was only about thirty inches high, just enough to keep a drunk or a child from falling out of the car onto the speeding tracks below. This was standard procedure for small trains without observation cars and though seemingly dangerous, really felt quite secure. I would take my station here as we approached the tunnel which became obvious when we entered a deep cut, then suddenly overhead became dark and we were in the tunnel with the light from the portal rapidly diminishing as it became more distant. This lasted only a short time, the tunnel was not long, maybe three or four city blocks, then we would bust out into daylight, the east portal would rapidly disappear in the distance and we would be back in people’s backyards and hog lots again. However, there was another big thrill to come almost immediately and that was the high Shuffle Creek trestle. The road had two such high ones, the Richland Creek Trestle near Bloomfield, 157 feet high and 2295 feet long, the highest, and Shuffle Creek 75 feet high a little shorter, both stoutly built of steel and quite spectacular. As we rumbled across this structure the metal wheels on track amplified the sound and the vibrations reverberated throughout the length of the bridge which was about one-fourth mile. After the trestle we soon came to the little settlement called Trevlac, named after the locating engineer for the railroad who’s name was Calvert. Trevlac spelled backwards. Then on to Helmsburg the only railroad stop in Brown County. There was always a modicum of business here because all mail and freight to the Brown County seat had to be brought through this station and then freighted over to Nashville by horse drawn dray. After a few minutes for this exchange we were on our way again. Morgantown, next stop, a large metropolis compared to Helmsburg, but not so big but what you could see both ends of town from the train station. More transactions, then Bargersville from which it was a straight shot to Indianapolis. All other hamlets and villages got their mail by the pick-up arm and hook that snatched it from the moving train. The whole trip was about 47 miles to The Indianapolis Union Station and took about an hour and a half which was regarded as damn fast in those days.

The Indianapolis Union Station was only three blocks from the center of the city. All shopping could be done by walking from one store to another in an area of one city block. We would have dinner (Never lunch, in those days) at a big cafeteria or restaurant, one of the main reasons for the trip, and then seemingly kill more time in the stores until time for the return train home. …

The return trip was a playback of the morning journey, everything in reverse order, until we arrived at our picturesque little station just at dark. As we approached home with the lights of our town showing brightly, everything seemed a little different and not quite so big as it had that morning because I had been to the city and had grown a little. …

The Monon, the railroad that ran by our mill and north and south through our home town, was the subject of great fascination to me as I grew up. Not only did I watch it out the windows of old Central School, but it was constantly in our lives as we heard its laconic whistle in the night and as we observed it on our trek back and forth from school to the mill and home. This was the culmination of the great age of the steam locomotive, the most powerful engines ever devised were just coming into use on the steep grades of the Monon through our town and indeed throughout the southern Indiana route of this fabulous little railroad.

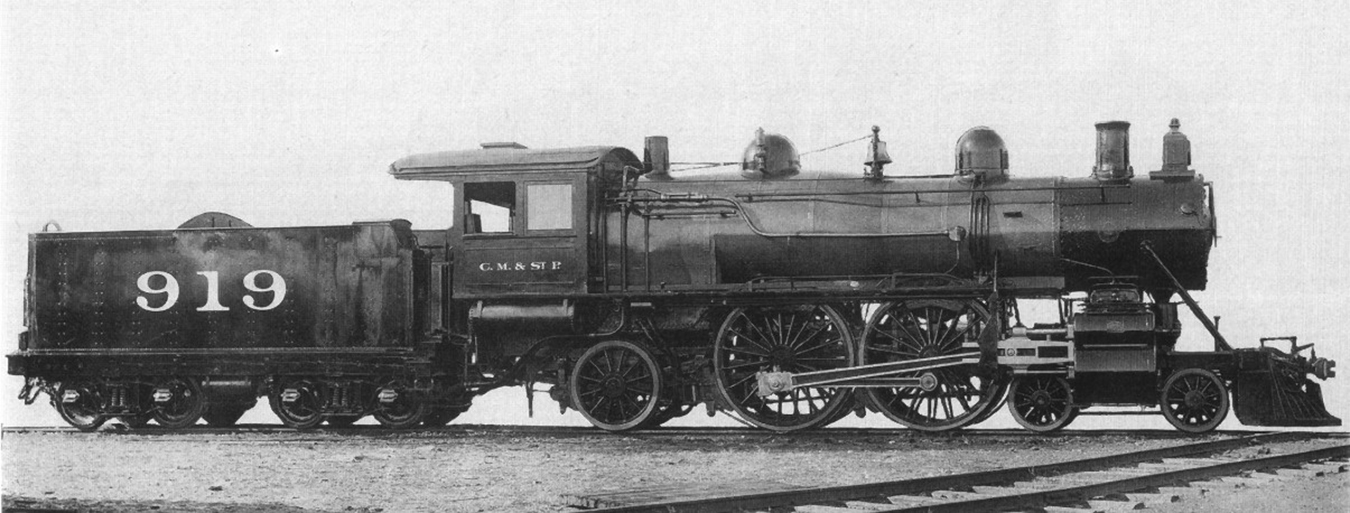

A 4-4-2 Atlantic type Pennsylvania Railroad Train, similar to the one in this photo, would come through town on its way to French Lick, Indiana. | Public domain

We were thrilled each afternoon when the crack passenger train whistled through never stopping. It was a special through-train from New York City to the Spa at French Lick Springs, in southern Indiana. It was operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad and used our little railroad on a trackage agreement for those miles involved from Indianapolis to French Lick. It had no scheduled stops, and consisted of a small Atlantic type locomotive of the typical Pennsylvania Railroad design, with the 4-4-2 wheel arrangement so characteristic of that classification. In addition, a baggage car and one coach that had been cut out of the New York to St. Louis express at Indianapolis. It was the only train allowed to negotiate our streets and crossings at any speed. And though it had slowed considerably, it went through town at what we thought was a thrilling pace, with whistle blaring, steam and coaches trailing behind. The engineer fascinated us with his head out the window and his goggles covering his eyes and looking straight ahead never noticing us little boys that waved frantically as he whizzed by. He knew he was making a thrilling passage and laid it on as thick as he could. This was the moment when we all decided we would be railway engineers when we grew up.

Our little line averaged a train every twenty-eight minutes in the daytime which gave us exposure to trains of all kinds. Especially thrilling were the northbound freights, climbing the grade under full steam with a heavy consist and whistling at every crossing. At night I lay in bed and listened to the whistles and clocked the trains through each crossing until they were over the hill and out of hearing. There can never be anything that can capture the imagination of a small boy more than a steam locomotive. …

[Publisher’s note: Want more of Bloomington’s history? Check out Limestone Post’s “A Sense of Place,” an art magazine commemorating Bloomington’s and Monroe County’s bicentennial. Our first print edition is available at these local stores and online.]