Bloomington is some 4,500 miles from Zurich, the same today as it was in the year 1916. But that winter, the distance between the two may as well have been measured in light-years.

In January of that year, Hugo Ball, a writer in exile from Germany, had convinced his friend Jan Ephraim to close his sleepy stube, the Holländische Meierei Café, and transform it into a nightclub. It would be a “third place” for artists, writers, and intellectuals who could engage in loud, lively discussions about the world and culture while enjoying avant-garde performances on its small stage. So, on February 1st, Ephraim threw the doors open for the fabled Cabaret Voltaire.

Carmichael in costume. He was in William “Monk” Moenkhaus’s inner circle of Dadaists who would often perform absurdist plays at the Book Nook. | Photo courtesy of Indiana University Archives of Traditional Music

The ragtag gang cooked up Dada, the world-shaking “anti-art,” anti-war, anti-bourgeoisie movement. Dada spread around the world even as the thrilling, mythical scene at the original Cabaret Voltaire petered out within a year.

But a Hoosier-flavored Cabaret Voltaire knock-off took root in downtown Bloomington, just off the Indiana University campus, in the early 1920s.

***

In 1914, young Bloomington-born William Moenkhaus, son of an Indiana University entomologist, found himself enrolled in a Gymnasium (prep school) in Zurich. While there, the teen was impressed by the burgeoning Dada scene.

America’s entry into World War I in 1917 caused his father to bring him home to Bloomington. Young William enrolled at IU in 1921, where he excelled at music composition. There, he struck up a fast friendship with Hoagy Carmichael. Hoagy called William “Monk.” Monk called himself “Wolfgang Beethoven Bunkhaus,” a pseudonym under which he published poetry and plays. The two and a coterie of like-minded musicians and oddballs hung out at the Book Nook on Indiana Avenue across from the IU School of Law.

The IU campus in the early 1920s was hot for “Negro” jazz, even as the Ku Klux Klan was experiencing a rebirth in Monroe County. The freaks and geeks at the Book Nook listened to jazz as they gobbled 15-cent sandwiches and swigged illegal “hooch.”

Monk was six feet tall and gaunt. He wrote poetry and essays for the IU literary quarterly, The Vagabond. It’s not known if Monk had ever met Romanian-born poet and performance artist Tristan Tzara while in Zurich, but the seminal Dadaist was a brilliant star of Cabaret Voltaire. He’d penned the Dada Manifesto in 1918. “Nothing is more delightful,” Tzara wrote, “than to confuse and upset people.”

Richard Sudhalter, author of the Carmichael biography, Stardust Melody, describes Monk’s writings as “lampoons of everyday situations and conversations, private jokes and improbable exchanges — echoing Tzara’s view that the absurd should hold no terrors because, seen objectively, life itself seemed absurd.”

Sudhalter paints a picture of Monk as “wraith-like” and “spectral,” spouting and writing made-up words and inside references that stunned the Jazz Age college kids who flocked to the Nook. Hoagy, in one of his several autobiographies, wrote of Monk: “Through his Dada and surrealistic nonsensical writings, he became a campus character. … As his writings progressed, he became the founder and chief spokesman of a campus cult which he named the Bent Eagles.”

The Bent Eagles held court at the Nook. As Monk wowed the crowd with his wit and insights, Hoagy plinked away at an old piano in a corner.

Historian Thomas Clark, in his book Indiana University, Midwestern Pioneer, wrote, “It was at the Book Nook that a segment of jazz was gestated and born.”

Hoagy himself has claimed he wrote the American classic “Stardust” at the place. He wrote in another of his memoirs, Sometimes I Wonder, “I sat down on the spooning wall at the edge of campus … and whistled a tune that became ‘Stardust.’ … I ran to the Nook, fearful of spilling the tune. … ‘Got to use your piano, Pete.’”

Monk (back row, center) became the chief spokesman of a group of absurdist artists he named the Bent Eagles. Carmichael wrote on the back of this photograph: “Some more crazy musicians from Indiana. Moenkhaus in fur collar, Eddie Wolf with bow and arrow.” | Photo courtesy of Indiana University Archives of Traditional Music

That was Book Nook proprietor Pete Costas, who ran the place with his two brothers. The Costas boys rented the first floor of the glazed white-brick, gabled structure that now houses BuffaLouie’s.

In the spring of 1924, legendary cornetist and composer Bix Biederbecke came to town with his touring band, the Wolverines. WFIU’s David Brent Johnson told the tale in a 2012 piece on his Night Lights blog (“The Road to Stardust: Hoagy Carmichael and Bix Beiderbecke in 1924”). Hoagy and Bix took to each other immediately. The two and other musicians rode on a flatbed truck on weekend nights, pushing off from the Nook and playing jazz in front of the fraternity and sorority houses along East 3rd Street. Afterward, Hoagy and Bix would lie “on the floor of Hoagy’s Kappa Sig house,” drinking illegal booze and listening to Stravinsky’s “The Firebird.” They’d wake up in the morning, stinking of alcohol, and head right over to the Nook to reconnoiter with Monk and the rest.

Hoagy called the Nook “King Arthur’s Round Table, a wailing wall.” Sudhalter wrote, “To watch [Carmichael] … was to behold a man possessed by a purity of expression wholly consonant with the ‘manifesto’ of Cabaret Voltaire days.”

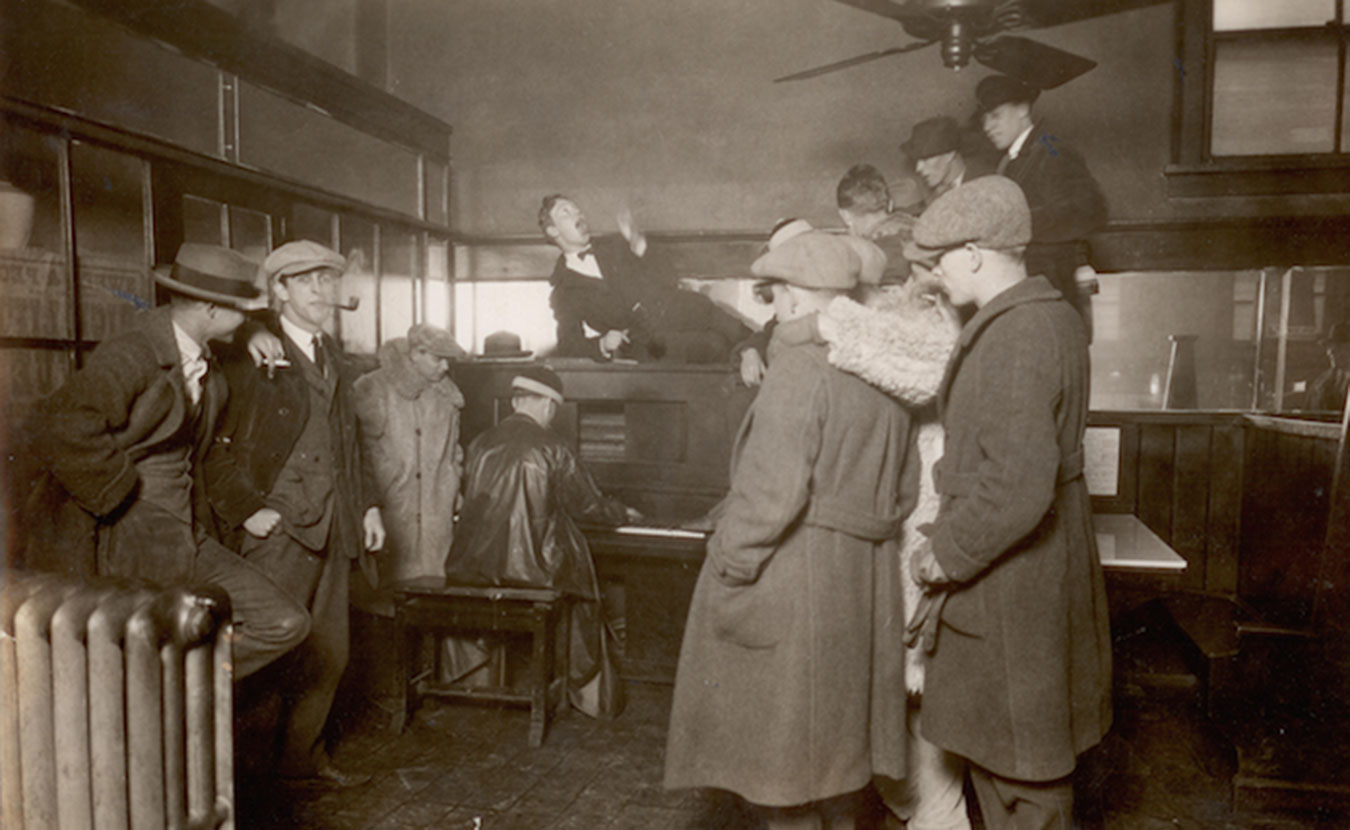

The Nook scene often resembled a mini-riot. According to Carmichael (via Sudhalter) the Bent Eagles spent their days and evenings “pelting one another with empty grapefruit rinds, stroking the creamy surfaces of meringue pies or throwing them, face down, on the floor, ‘just to hear the sound’; carrying on ear-splitting, explosively monosyllabic exchanges. …”

Hoagy once wrote of Monk’s — and by extension, the Bent Eagles’ — world view: “Why take it so seriously? Why not tear down everything that Man has accomplished? Why go in the same old rut?”

Monk was a brilliant, almost transcendent student, but he lacked direction. He filled out a form for his permanent student record estimating he’d graduate sometime around 1950. In fact, he failed a Hygiene class in his senior year, preventing him from graduating with his peers in 1926.

By then, town and university officials had grown weary of the hell-raising, illegally boozing denizens of the Nook. In 1927, the Costas boys were charged with operating a public nuisance. They were found guilty and fined $500, with Pete earning a suspended 30-day sentence in jail.

Two weeks later, Pete held a mock “commencement,” thumbing his nose at the authorities and giving Monk the “graduation” he deserved. There were celebrity guest speakers, IU faculty members wearing their colors, and diplomas in Coke-ology and Nook-ology. Hoagy, who had graduated in 1925, led a marching band dressed in robes and fezzes to the dais on Indiana Avenue. Monk was given a Doctor of Discord degree. (Hoagy received the same honor the next year.)

The bash was so popular, with at least a thousand in attendance, that Costas made it an annual affair. A Pathé newsreel of one year’s “commencement” even played in theaters around the country.

Carmichael (front, with cornet) leads the parade to a mock “Commencement” at the Book Nook in 1928. | Photo courtesy of Indiana University Archives of Traditional Music

Hoagy earned a law degree in 1926 and went to work for a local firm. He didn’t do much legal work, preferring instead to write songs and play gigs whenever he could.

Monk finally graduated with high distinction, for real, in 1929. He went on to study at the Detroit Conservatory. Two years later, he died of a ruptured stomach ulcer.

The year Monk died, 1931, the Costas’s landlord ousted them, closed the Nook, and opened a restaurant called The Gables. By then, Hoagy was well on his way to fame. The old Zurich home of Cabaret Voltaire was still more than 4,500 miles away.

Monk

William Moenkhaus — aka William Beethoven Bunkhaus, Lena Gedunkhaus, Oscar Humidor Martin, Roland McFeeters, or just plain Monk — had an important influence, musically and philosophically, on Bloomington-born Hoagy Carmichael, who would later write such jazz standards as “Stardust,” “Georgia on My Mind,” “Skylark,” and scores of others, including the Oscar-winning “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening.” Monk, on the other hand, was winner of Indiana University’s prestigious Grace Porterfield Polk music scholarship and had musical talent said to be “of the pure lineage of Bach and Mozart.”

But Monk was also a disciple of Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp, and other founders of the Dada “anti-art” movement in Europe. As an IU student, Monk effectively imported Dada to Bloomington, making its home the Book Nook soda shop on Indiana Avenue. Monk, Hoagy, and their friends held court at the Nook, a scene of “overheated discussion and spontaneous, often outrageous behavior (with hot jazz as both a soundtrack and counterpoint),” wrote Richard Sudhalter in his Hoagy biography, Stardust Melody. The book was published in 2002, more than 20 years after Hoagy’s death and 70 years after Monk’s. Both Hoagy and Monk are buried in Bloomington’s Rose Hill Cemetery.

The following poem was published in IU’s literary magazine, The Vagabond. Very likely, though, Monk began composing and reciting it at the Book Nook. Think back to the 1920s … a short, wiry guy playing jazz on the piano in the corner of a crowded soda shop … the smoky room filled with noisy students … a tall, gaunt man stands in the middle of the crowd, his “spectral” features gathering everyone’s attention. … As the piano plays, he recites …

The Years Have Pants!

by William Beethoven Bunkhaus

The years have pants! Yon

Helmet of the sunburn gone,

Lingering odors of the dead

Who yesterday the wigwam fed.

’Tis not the grave of Hermann Burt

Whose life was like an ugly wart,

Fold up the trumpet which he drove

And pour the music in the stove!

’Twas his to live and now to die.

Who remembers not the pie

That each and every evening went

Into a mouth that now lies bent?

A tear or two, then from us sweep

The memories of men who sleep.

Long live the drunken alphabet!

The time for us has not come — YET.

No Replies to "Dada a la Bloomington — a 1920s ‘Anti-Art’ Hotbed"