“I want flow,” says Jennifer Brooks, bicyclist and community advocate. “There’s lack of consensus in the community around bicycling. We make bicyclists inhabit a lane to the ire of drivers. My dream is to have consensus, where you have drivers, bicyclists, pedestrians, all coexisting and getting where they want to go.”

The recent passing of a $10 million bond for trails, greenways, and gateways allows for a new conversation to begin about infrastructure, our built environment, and how we want to interact with it. | Limestone Post

For the past couple of years, I’ve been fascinated by the video of San Francisco before the 1906 earthquake. There is an immense rhythm and choreography to the streets at that time — streetcars, pedestrians, cyclists, horse and buggies all in a ballet of urban movement. While looking back through the lens of nostalgia can be a tool for oppression and pain, I still find that this video illustrates the potential for multiple users to engage with their surroundings. With the introduction of PACE bike-share, Bird and Lime scooter companies, and the recent passing of a $10 million bond for trails, greenways, and gateways, a new conversation opens up about how we interact with infrastructure and our built environment.

Right now, Bloomington is at a crossroads — culturally, civically, and economically. This city is in a time of immense reflection and self-discovery, not only due to citizen-led initiatives but also through City-led projects. Within the past year, the City adopted a Comprehensive Plan and a Sustainability Action Plan and is currently reviewing and updating the Urban Development Ordinance and Transportation Plan. Furthermore, city council recently passed a new fee structure to the downtown parking infrastructure. These guiding documents give the City and community a map to follow for decision making over the next ten years.

But before we go there, let’s look at our current downtown and how we interact with it. College Avenue and Walnut Street are the internal north/south “highway” system of the city. This outdated design comes from the Urban Renewal approach of the 1950s and ’60s, which was an urban planning strategy designed to uphold white/class supremacy in our cities, towns, and suburbs, fostered by redlining and the disinvestments of downtowns all across the country. As a community, we need to consider how this “highway” is used today. Does Bloomington want to encourage access to the downtown or get people through as quickly as possible? Though it’s not as obvious in Bloomington, the general design flaw of urban areas since the 1960s has been to move traffic out of downtowns and quickly to suburbs. Think about the fact that there are six full lanes devoted to moving drivers through downtown swiftly rather than helping them to engage with it, not to mention the lack of a single dedicated bike lane on College/Walnut through the main downtown area.

“Infrastructure shapes our behavior, and we get the behavior we design for,” says Beth Rosenbarger, the manager for the City of Bloomington’s Planning Services. This is demonstrated downtown by bicyclists who use Lincoln, pictured here, and Washington as through-streets to avoid car-focused College and Walnut. | Limestone Post

“Infrastructure shapes our behavior, and we get the behavior we design for,” says Beth Rosenbarger, the manager for the City of Bloomington’s Planning Services and formerly the bike and pedestrian coordinator.

So where does our bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure fit into all this? Recently, I wrote an article exploring the vast and diverse options available for riding around Bloomington. But the question still lingers: Can we be the Biking Capital of the Midwest?

To achieve that goal, this town can’t simply rely on the natural resources, state forest preserves, and surrounding parks. Recreational cycling is one small aspect of a bicycling community, and, usually, it’s one of privilege and choice. To become the Biking Capital of the Midwest, the City and community can’t just plan for it, they have to build it — more connective greenways and shared streets in which cars, pedestrians, and bicyclists all occupy their own space. Protected bike and mobility lanes throughout Bloomington (scooters and motorized skateboards: you’re fine here, just not on the sidewalks, okay?). And ideally, an east-west protected bike infrastructure similar to the north-south corridor created by the B-Line.

It’s also essential to note that vocabulary matters in this conversation as we address equity, access, and inclusion. Terms such as “cyclist” and “bicyclist” have different connotations for people — it either includes someone dressed in spandex and funny-colored socks or someone who uses a bicycle as a necessary mode of workday transportation. It is also important to acknowledge that there are “Invisible Riders,” particularly low-income bicyclists who lack representation at key decision-making discussions.

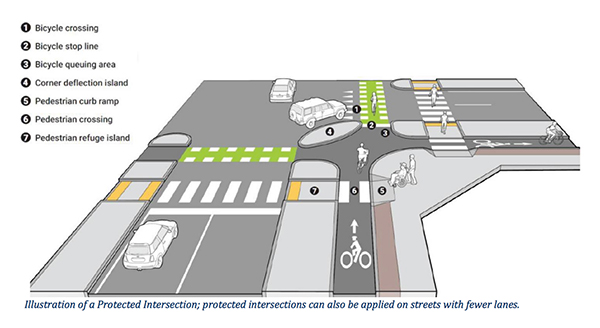

This image from the City of Bloomington Transportation Plan shows what an intersection would look like with protected bike lanes. Currently, Bloomington does not have any protected bike lanes. | Courtesy Image

According to Rosenbarger, the City hasn’t provided sufficient infrastructure needed for the daily bike commuter. “As a community, we set the mark that we want to be a Platinum Ranked Bicycling Community,” she says, referring to a designation through the League of American Bicyclists. “In 2011, we hosted the Platinum Summit — our goal was to reach that designation in 2016. If we are measuring against that, we have failed. There are certain clear metrics we haven’t hit. We are trying to move toward this [goal], but we aren’t moving there fast enough. For example, we don’t have a single protected bike lane on a single city street.”

It comes down to a series of questions around what we value — as a city and a community. In all of these plans, council meetings, and guiding documents, we say we want more sustainable approaches, more greenways, more connectivity, and more pedestrian infrastructure; yet, the car (and how we design for it) dominates every aspect of this town’s urban fabric and infrastructure. It’s time to invest in the design and infrastructure the City and community claim they want, rather than overlook the lack of bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure within city limits. Think about the ideas, such as greenways, mentioned earlier.

Change is always hard. Lime and Bird represent disruptive technologies that, in my opinion, offer more sustainable alternative transportation. While, yes, change is stressful and can create anxiety at first, it helps us think through new patterns of engagement and street use within our city, while also slowing cars down. While it takes time for things like this to settle and for a community to adjust, I believe it’s progress.

![(left) A mural by Justus Roe at the bike and pedestrian underpass at 7th Street and the Bypass. | Limestone Post (middle) Bloomington residents have recently gained access to new modes of alternative transportation, including PACE bike-share, pictured here, and Bird and Lime scooters. | Limestone Post (right) Starowitz took this photo on his commute to work. “The bike lane on College as soon as you hit the north end downtown turns into a sharrow [a shared lane],” he says. “It essentially disappears. Exactly where you want traffic to slow down, you force bicyclists to merge with ongoing traffic. Note — posted speed limit is 25 miles per hour.” | Photo by Sean Starowitz](https://www.limestonepostmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/CityBike10.jpg)

(left) A mural by Justus Roe at the bike and pedestrian underpass at 7th Street and the Bypass. | Limestone Post (middle) Bloomington residents have recently gained access to new modes of alternative transportation, including PACE bike-share, pictured here, and Bird and Lime scooters. | Limestone Post (right) Starowitz took this photo on his commute to work. “The bike lane on College as soon as you hit the north end downtown turns into a sharrow [a shared lane],” he says. “It essentially disappears. Exactly where you want traffic to slow down, you force bicyclists to merge with ongoing traffic. Note — posted speed limit is 25 miles per hour.” | Photo by Sean Starowitz

Progress isn’t possible through merely adding resources. Once again, it’s how public infrastructure is designed.

“We just can’t keep adding more bicycles to car streets and think that will increase ridership,” says Jane St. John, the consultant who worked on the IU and City partnership with PACE bike-share. “We need to make it more comfortable for people to ride bikes — though I think we need some predictability of where the bikes should go, because the idea that bicyclists can be comfortable on all streets isn’t true.”

This image was from the Allen Street Greenway project. According to the website, “This project uses temporary materials including speed cushions and bump-outs in order to reduce motor vehicle speeds and increase comfort and safety for pedestrians and bicyclists on East Allen Street. This street was identified as a Neighborhood Greenway in the Bicycle and Pedestrian Transportation and Greenways System Plan. The temporary materials and pilot installation allow for residents and greenway users to provide feedback before committing to a permanent design for the Neighborhood Greenway.” | Photo by Jim Rosenbarger

For some, this becomes a reality when biking for daily transportation. “It can be really challenging to get around Bloomington,” says Sarah Kopper, an avid bike commuter since 2004. Kopper is part of a carless family with two kids and uses cycling for transportation, not recreation. “Even though it can be difficult, at the same time, Bloomington is so compact, usually everything is within two miles for us — we were specific on where we chose to live, proximity to amenities. I’ve gotten spoiled. If I have to ride more than 5 miles, it’s a trek.”

In terms of successful progress, I think what’s missing is an outside group pushing the City to think differently about infrastructure. Essentially, the Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Commission is a “subsidized lobbying group,” says Jim Rosenbarger, member of the Bike-Ped Commission. And its projects “depend on the members and what they want to take on.” Commissions are made up of volunteer members of the public who either the mayor or city council appoint to act as an advisory committee to the City on specific projects.

While commissions have assisted the City in various capacities, outside of City Hall we don’t have a standalone group pushing for more. There is a variety of ways in which both have advantages and disadvantages. Some recent examples are the recommendations brought forth by the City Parking Commission and the IU student advocates that lobbied for the City to rename Columbus Day to Indigenous People’s Day. Another group that was instrumental in pushing the City and advocating for equitable infrastructure was our local Open Streets program, which was dismantled in 2017. Other groups exist but haven’t been vocal or active enough to make an impact on legislature.

“It’s pretty clear we have the will of City Hall and the Bike-Ped Commission to be progressive in policy and infrastructure, and maybe that will is more than most Bloomingtonians,” says Jaclyn Ray of the City of Bloomington’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Commission.

So what is the will of Bloomington? Do we want to be a Biking Capital of the Midwest? If so, we’ve got a long road ahead of us, but I guarantee it won’t take as long as building, say, an interstate through town.

How to get involved

The City is always looking for citizens/residents to join commissions — please check out the link and apply.

If you’re curious about how to bike for transportation, check out Sarah Kopper’s Family Pedals Podcast, which features interviews with families living car-free or car-lite.

The national Open Streets Project is “part advocacy project, part toolkit, part information database.”

The Project for Public Spaces, Inc. program Bike Walk, officially named the National Center for Bicycling & Walking (NCBW), has been around for decades. Their mission is to create more bicycle-friendly and walkable communities throughout the U.S. Check out their website for more info on how to get involved.

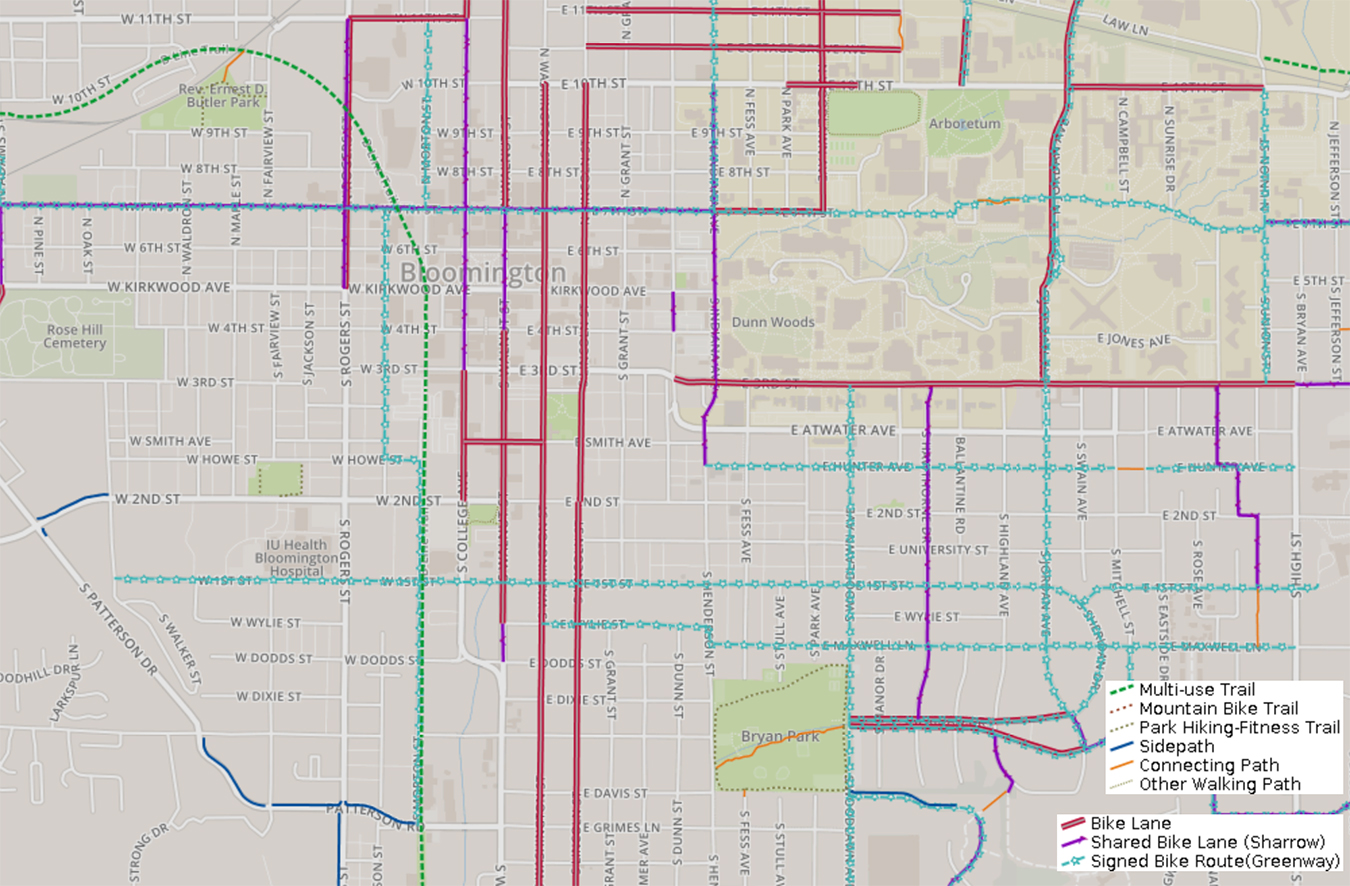

This map from the City of Bloomington shows bike and trail routes in the downtown area. Click here to see the complete version. | Courtesy image