He’s often known as “Mr. Two Time.” A two-time Indianapolis 500 winner, two-time International Race of Champions winner, and two-time IndyCar season champion, Al Unser Jr. is racing royalty. As the son of the famed Al Unser and nephew of Bobby Unser, Al Unser Jr. grew up on the fumes from Gasoline Alley, fostered under the tutelage not only of his father and uncle but also racing legends like Mario Andretti, Emerson Fittipaldi, Dale Earnhardt, Roger Penske, and others. Growing up in racing, a kid like Unser got used to living life at speeds over 200 miles per hour.

On the racetrack, Unser lived life on the edge. But he has not translated his racing success off the track, where a history of alcohol and drug abuse has followed him for most of his career.

In March, Jade Gurss (left) and Al Unser Jr. greeted fans and signed their book, ’A Checkered Past,’ at Morgenstern Books in Bloomington as part of a book tour throughout Indiana. | Limestone Post

His recent book, A Checkered Past (Octane Press, 2022), tells a multifaceted story about Unser. With co-author Jade Gurss, whose other books include Dale Jr. Download, Driver #8, and Beast, Al Unser Jr. delves into the Unser family and their place in the racing world and their influence on his racing career.

The book begins with the younger Unser holding a loaded gun to his head. In 2012, on his 50th birthday, Unser decided to commit suicide, saying that he’d reached a crisis point. He’d become a drug addict and alcoholic. He was retired from racing, fired from the Indy Racing League as an official, and was in the midst of a deep depression. As he says in the book:

“It’s like falling down the rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland. I had been able to pull myself out of the hole a few times. Now I wasn’t able to climb out.”

He doesn’t say in the book why he didn’t go through with it, but even now, that past dominates Unser’s story. Charged in 2007 and 2011 with driving under the influence, and in one of those cases a misdemeanor hit and run, Unser has avoided actual jail time for charges. His most recent DUI was in 2019 when Unser reportedly lost his balance in a field sobriety test and rolled down an embankment. For this charge, Unser got his driver’s license suspended for a year, received a 365-day sentence that was suspended, and was required to do 480 community service hours.

Even in telling his own story, Unser is elusive about his personal life. We don’t know how it impacted his family, his children. As subsequently reported in a Motorsport magazine article, “Al Unser Jr.: Fall from grace,” we don’t know why Al Unser Sr., upon receiving a draft copy of A Checkered Past, never acknowledged it to his son. Though the younger Unser freely admits he wasn’t “made for jail,” and that rehab or Alcoholics Anonymous didn’t work for him, he often seems unaware that he hasn’t been held fully accountable for his actions.

The final chapter of his book finds him committed only to the simple goal: “I want to live a life led by Jesus.” That, he says, is his solution to his addiction.

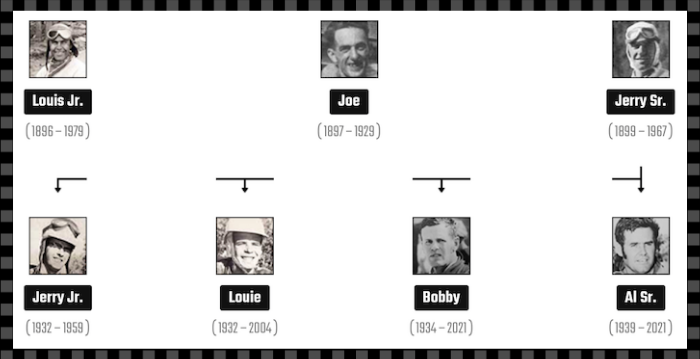

Unser’s book, though, is at its finest when it covers the racing world. Anyone who knows even a little about racing knows the impact of the Unser family on the sport. Winning the Indianapolis 500 nine times, they are stalwarts in the racing world, a standard to which race car drivers even today aspire. The photos on their family tree literally show men in racing goggles and helmets as early as 1915. So racing is in their blood.

In A Checkered Past, you get a lap-by-lap account of Unser’s racing career with some of his personal life thrown in. And while his racing world is a thrilling ride, the reader knows only what Unser wants us to know about his personal life and how, if at all, it connects with his racing life.

A racing dynasty begins

The Unser saga starts in Colorado at the base of Pikes Peak in 1915, where three Unser brothers, Louis Jr., Joe, and Jerry (Al Jr.’s grandfather and great uncles), are the first to scale the famous peak in a motorized vehicle. The brothers conquered the treacherous climb of 14,114 feet on dirt and gravel roads with sharp hairpin turns. In 1916, the first Pikes Peak Auto Hill Climb event was created.

Racing is an Unser tradition. This image from their family tree (courtesy of the Unser Racing Museum) shows several members in racing goggles and helmets. In 1915, Al Unser Jr.’s grandfather Jerry and great uncles Joe and Louis were the first to scale the 14,000-foot Pikes Peak in a motorized vehicle. The next year, the Pikes Peak Auto Hill Climb (now the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb) became an annual event.

In 1978, on his 16th birthday, Al Unser Jr.’s father gave him a birthday card with the inscription, “Happy Birthday. We’re going to Pikes Peak this year.” In family tradition, the younger Unser tackled the peak over the course of several days, first running the bottom section, then the middle, and finally the top segment of the peak on the third day.

According to Unser, “I almost drove it off the road several times, which would have meant tumbling down the side of the mountain like a rag doll! I don’t know how many times I almost crashed.” He finished the race, but admits in the book, “I was way too immature.”

From an early age, Unser knew he was destined for racing, despite saying his father never pushed him. But the racing life is all that he has ever really known. Even from the very onset of A Checkered Past, Unser makes the shocking statement that both his father and uncle Bobby lived by the mantra “It’s not cheating if you don’t get caught.”

They lived to win by any means. The phrase applied to racing, but also to life itself. If you don’t get caught, what’s the problem with cheating with your race car or on your wife.

Throughout the book, Unser never elaborates or even shares any incident where cheating was involved either professionally or personally by his father or uncle. What he does detail is the relentless push to win, at all costs, at racing, an attitude that Unser inherits and pursues throughout this racing career. In 2021, Unser’s father Al, uncle Bobby, and first cousin Bobby Jr. all died within seven months of each other.

Al Unser Jr. and his wife, Shelley, moments before the 1991 Indianapolis 500. He would finish 4th in the race.

For those who casually watch racing, how a race car driver is built from the ground up is often not part of their consideration. Those fans merely want to see an exciting race. But what they may not know is the learning curve that racers must master. One of the fascinating aspects of A Checkered Past is its intimate details of learning to race. Al Jr. gets his start by racing go-karts at nine years old. Reading about those “pointers” from his father and uncle are some of the most interesting parts of the book, as the younger Unser figures out the value of the “line” (the fastest way around every corner) and what a corner apex is (the point on the inside of the corner where you can apply the throttle again).

Race car drivers also have to figure out what type of racing they want to pursue, for the choices are many. Unser also describes how he had to define what style of racer he was going to be. Was he going to race like his father or his uncle? Like Uncle Bobby, who wanted to be the fastest thing on the track because, Unser writes, “in his era, the cars weren’t very reliable, so he wanted to be leading if his car broke.” Or like Unser Sr., who believed that leading at the end of the race was when it mattered the most. As Al Jr. puts it, “He would tell me, ‘There is only one lap you want to lead. The last one. The rest is a waste.’”

Finding his own path

From the beginning, Unser Jr. experimented with racing styles from stock car to F1 to IndyCar. But one thing he always had was an innate sense for the car, and it stayed with him for the rest of his racing career.

“I tried to take the best of Uncle Bobby and the best of Dad and meet in the middle. I tried to have Uncle Bobby’s willingness to throw it all out there but have my dad’s temperament and consistency. If I could get the best of both worlds, that’s what I tried to do throughout my career.”

In 1971, Unser’s parents divorced, which had “strong repercussions” in his life, he writes. He bounced back and forth between his mother’s and father’s homes, with his father providing a more disciplined household when he was home. His older sister Debra died in a dune buggy accident in 1982, and Mary, the oldest sibling, died of a brain aneurysm in 2009. All these incidents, Unser says, are part of his depression and were an extensive part of his therapy and rehabilitation.

Al Unser Sr. with his second wife, Karen Sue Unser, in 2015 at the 500 Festival in Indianapolis. | Photo by Sarah Stierch, via Wikimedia Commons CC BY 4.0

As the only son, Unser admits he was spoiled by his mother and could get away with anything — playing his mom against his dad. “Women taking control of my life — taking care of everything — started early for me,” he writes.

But with his dad, racing became the incentive to toe the line.

“There were days when I would get out of school, and Dad would already have the go-kart loaded in the back of the truck. I’d put my schoolbooks in my bedroom, and we would go to the track. We had to lift the kart over the fence because it was closed. We’d fire it up, and I’d pull onto the track.”

By age eleven, Unser was racing sprint cars, high-powered open-wheel racing cars designed to run on a short oval track, much like the quarter-mile dirt oval at Bloomington Speedway, and other area tracks. Then after high school, he entered the World of Outlaws series for sprint cars. The outlaw label, he says, applies to “racers who would travel across the country like gunslingers, finding big-money races where they could win cash and trophies from the locals.” Unser met his first wife, Shelley Leonard, during these races. “Blonde hair. Big eyes. Great smile …” he recalls. “She was beautiful. Simply beautiful.” He married her in 1982 and divorced her in 1999. She died in 2018 of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

At Unser’s debut at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1981, he drove a 1968 Ferrari Daytona. “A gorgeous car. A brilliant car,” he says.

The first time I drove the car in practice, I realized it had a speedometer. In that era, there was no Bus Stop chicane. You’d go down the backstretch right into the high-banked NASCAR Turn Three. As I got to the end of the back straight, I glanced down to see I was going 180 miles an hour. That scared the shit out of me! I came back to the pits and begged, ‘Please tape over the speedometer. I don’t want to see it.’ I was fine as long as I didn’t know how fast I was actually going.

Unser’s debut in Formula Super Vee was with Rick Galles’s racing team in 1981 at the Charlotte Motor Speedway. On his father’s advice, he moved into CART (Championship Auto Racing Teams, a predecessor to today’s IndyCar series) in 1982, winning the series in 1990. Though he continued with Can-Am (Canadian-American) racing, he says, the focus in 1982 “was always on becoming a top contender in CART.” He ran his first Indy 500 in 1983, also competing in the International Race of Champions (IROC), winning in 1986 and 1988 as the first IndyCar driver to win an IROC championship.

As for any race car driver, the ultimate draw is the Indianapolis 500. Unser was twenty years old the first time he raced at Indy, in 1983, qualifying 5th and finishing in 10th place, while racing against his father, who finished 2nd. The race left him with considerable emotions as a first-time driver. It was uplifting and, at the same time, depressing, he says.

The immortals had become mortal. Foyt, Johnny Rutherford, Johncock, Andretti. They were just like me. … I had them on a pedestal. They were racing legends carved in stone. But now? Only men. Flesh and blood. To me, it was profoundly sad.

For the Unser family, years of racing at “the Brickyard,” as Indy is known, ultimately translated into nine wins: four for Al Unser Sr., three for Bobby Unser, and two for Al Jr. About winning the Indy 500 in 1992 for the first time, he says:

You just don’t know what Indy means. It meant so much, but even now, I can’t put into words what Indy means. The pain and the suffering and the joy and the happiness of all the years. My uncle Jerry lost his life there before I was born. The pressure of who my uncle and dad were, and what they had accomplished in this race. … Early the next morning, when we were taking the traditional winner’s photos on the yard of bricks with my family, my crew, and the Borg-Warner Trophy, it began to settle in my brain. Only then can you start to understand what has been accomplished.

For the Unser family, the Indy 500 is the ultimate prize that drove them to compete even against each other. One of Al Jr.’s wins is still remembered as one of the closest margins of victory in the history of Indy racing. He retired from IndyCar racing in 2004.

A victory lap

By detailing Unser’s racing experiences, A Checkered Past takes a victory lap on his career. The reader feels as if they were at the race with the roar of a car at 200-plus miles per hour, taking their breath away. The book gives the reader a real sense of what it is like to grow into racing as a profession and the challenges required to stay on top. It also excels at distinguishing between the variety of racing series (like Formula One, NASCAR, and IndyCar), venues, and team owners that make up the racing world and their impact on a racing life.

Al Unser Jr. grew up “on the fumes from Gasoline Alley” at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, writes Rebecca Hill. Before entering his first Indy 500 in 1983, Unser says he held racing legends like A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, and Johnny Rutherford “on a pedestal.” | Limestone Post

Without a doubt, racing is a sport that only a select few can do. A Checkered Past makes it clear throughout the book that Al Unser Jr. has an innate sense for the car and the road on which he is racing, even from an early age.

Once I had learned that in the go-kart, I could apply it to anything. I could see it. I don’t know why, but it came easy. Also, I learned the feel of a race car, the balance of it, whether it was pushing the front or loose in the back, or if the engine sounded off-song. If the kart needed a different gear ratio, I could recognize that.

But what Al Unser Jr. doesn’t seem to have is a sense of what life is like after the car is driven into the garage. The speed of racing translates into his personal life and living his life at the same speed was his frequent downfall.

An admitted drug user, Unser acknowledges that he was professionally never held accountable for his drug use. He rationalizes, “If IndyCar had the same intense and robust drug testing policy it has now, it might have helped me kick the drugs at a younger age.” Drug use, too, permeated his household — his wife, Shelley, with cocaine addiction. Unser believed that because he had marijuana, she had permission to have her drugs within the home.

To this day, I believe if I were not a pot smoker, then no other drugs would have been allowed. Shelley and I would have been ‘against’ drugs. She would look at me and say, “You have your drug. I have my drug.”

Unser and Shelley divorced in 1999, with Shelley convincing the judge that Unser was a “danger to her and the kids.”

“My four kids hate me,” Unser says in the book. He was served with a restraining order that, Unser writes, prevented him from seeing the kids. According to an ESPN article by Robin Miller, the restraining order was issued over alleged abuse against Shelley. The article also reports that his four children would become scared when Al Jr. drank too much. The same article reports several incidents where Unser was violent when drinking. In the book, we never get a sense how their drug and alcohol use, from Al or Shelley, impacted the household. When Shelley showed up drunk at the racetrack, or “my place of work,” says Unser, that was the final straw for him. It was Shelley’s drug use that Unser claims in the book ended the marriage. Not Unser’s. Since Unser had been able to keep it off the track, he was, in his mind, in the clear and the divorce was no fault of his.

The Unsers had four children. Throughout the book, the reader learns virtually nothing about his four kids and their participation in his life, racing, or at home, or the impact of the divorce on his children. Yes, a restraining order is in place. But we never know what kind of order it is. Is he prevented from seeing the kids at all — not even with supervised visits? Does it last forever? The reader never knows. We only know what Unser tells the reader. While he regrets not being a better father, it is Shelley again whom he blames.

My kids loved me one day and hated me the next day. To this day I have an estranged relationship with my kids, especially my daughters. It hurts me deeply. Shelley painted everything as my fault. I was the devil, and she was the angel who never did anything wrong.

In A Checkered Past, we see two Al Unser Jrs. — one who is successful at racing and another who fails at his personal life. But they never connect.

In A Checkered Past, we see two Al Unser Jrs. — one who is successful at racing and another who fails at his personal life. But they never connect.

When Unser finally retires from racing in 2004, his personal life overtakes him, and he can no longer cope, no matter how many rehab centers he visits. The starting gun of his racing life and stardom saves him from the clanging door of an extended jail stay. But it is replaced, in 2012, with a gun pointed to his head, a trigger never pulled.

Unser concedes numerous times in the book that he recognizes that he has a disease, even sharing it publicly in 2007. But what he never admits is that he is responsible for controlling any outcomes of that disease. With two prior arrests, he was arrested again in Avon, Indiana, in 2019.

I pled guilty to the charges in August [2019]. My attorney made a deal with the court for community service instead of jail time. I got 363 days of probation and 480 hours of community service. I also received a one-year suspension of my driver’s license but was granted special privileges to continue driving to work. I was relieved about no jail time. I couldn’t have handled that. I’m not made for jail.

Unser now stays clean by relying on his faith in God, he says, to provide him with the strength he needs to manage his addiction, conceding that he’d tried everything else — rehab, AA, Soberlink, and “anything that I could find.” None of it worked, he says. So he believes that he had to give Jesus a serious try.

In my race car, I sought perfection. I lived it. I breathed it. Some days I achieved it. But it was a much bigger struggle outside of the race car. The substances took me away from the pain of not being perfect. They cause a lot more pain in the process. I still strive to be perfect, but I don’t have to be. I thank God for my imperfection.

In the end, Gurss and Unser write a book that racing fans will enjoy. It tells the story of a race car driver and a man — one who wanted perfection on the track and the other who couldn’t find perfection off the track. Unser concedes that he is not done yet. He has been sober since 2019. He has a new partner who, he says, “accepts” him. He is currently the director of competition for the Formula 4 team Future Star Racing, helping young race drivers learn the value of the checkered flag.

A checkered past or not, Al Unser Jr. is a survivor who’s only just beginning.

Thank you to our Underwriter!

This article was underwritten by Morgenstern Books. You can find A Checkered Past by Al Unser Jr. and Jade Gurss at Morgenstern’s online shop and in the store at 849 S. Auto Mall Rd. in Bloomington.

Morgenstern’s is Indiana’s largest independent bookstore. We thank them for their support!