Sharon Mead, an oncology nurse navigator for the Lohano Center for Advanced Medicine at Daviess Community Hospital, has had cancer twice — once in 2007 and the second time in 2014. She had two different kinds of breast cancer and survived both. Since 1994 she’s worked in oncology, which means Mead knew cancer intimately even before she had it. But still, her life’s work is helping cancer patients every day, knowing that she too could have a reoccurrence of her cancer. “I am a cancer survivor myself,” she says. “I don’t want my patients to think that I am someone on the other side of the fence who doesn’t understand the feelings and emotions of cancer.”

Those words, “Cancer … You have cancer,” shock a person into submission and seed a fear that stays with a person forever. For some people, survival depends on the type and stage of cancer and how they work their way through the cancer to-do list. They gear themselves up for the fight. For others, it means paralyzing inaction. For everyone, however, dealing with cancer requires help. It’s not a single-issue disease. Having cancer requires a continuum of care, and an army is needed to defeat it.

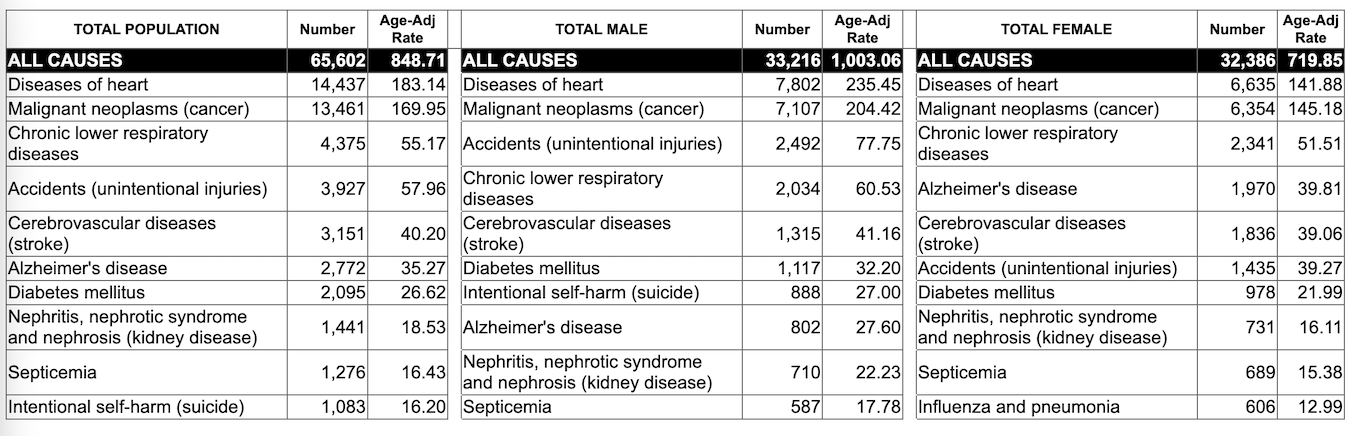

But cancer is not the curse that it once was. According to American Cancer Society Cancer Facts and Figures 2022, “The overall age-adjusted cancer death rate rose during most of the 20th century, peaking in 1991 at 215 cancer deaths per 100,000 people, mainly because of the smoking epidemic.” But since then, as of 2019, cancer rates declined 32 percent. Between 1991 and 2019, there were an estimated 3.5 million fewer cancer deaths because of progress against lung, colorectal, breast, and prostrate cancers.

Source: American Cancer Society

What caused these drops? A multitude of factors. Increased screening for cancers. People change their habits, such as quitting smoking or losing weight. Better nutrition. More exercise. Plus, research has created more encouraging treatments and surgeries. For some cancers, death is no longer the endgame. People like Sharon Mead are surviving cancer, and in fact, some people, even if they are in stage four, are managing their cancer into longer lives.

Disparities in rural cancer care

But in rural areas, the cancer story presents a different, more distressing chapter. Progress in reducing mortality rates for cancer in rural communities is slower. Rural populations have lower screening rates and higher incidence rates of preventable cancers like breast and colorectal cancer. Access to clinical trials and treatment options is limited. As a result, rural residents often don’t seek care until they have reached a more advanced stage of the disease.

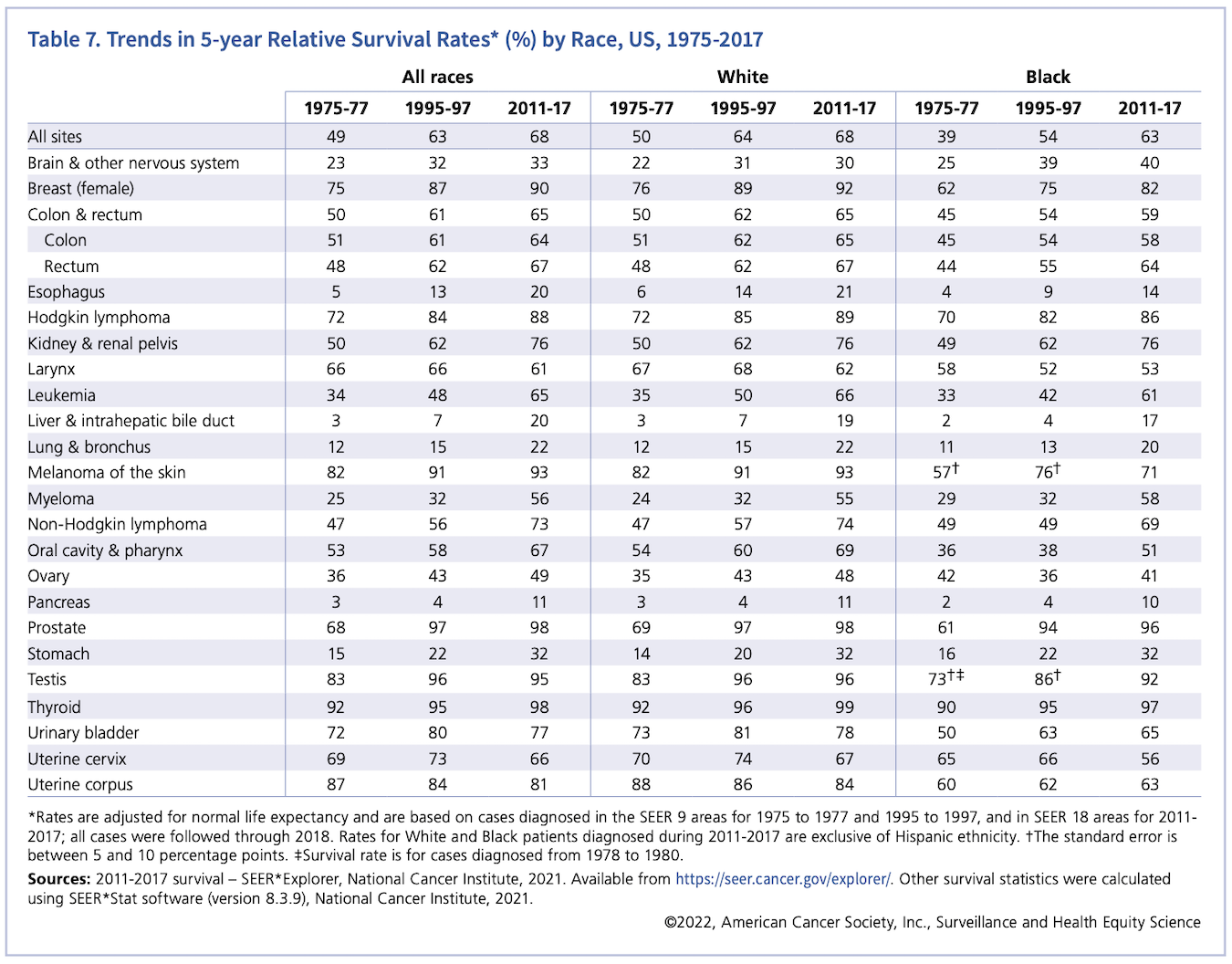

According to the 2017 Indiana Mortality Report, cancer is the second leading cause of death behind heart disease in Indiana. Looking at southern Indiana counties, the report shows that in Lawrence County, 20 percent of patient deaths were due to cancer (178.3 deaths per 100,000 people) with Orange and Brown counties respectively having 25 percent and 24 percent. According to the American Cancer Society, Indiana’s estimated cancer deaths decreased by .15 percent between 2017 and 2022, while estimated cancer deaths increased by 1.4 percent in the U.S. overall.

The Indiana Cancer Control Plan, developed by the Indiana Cancer Consortium, monitors cancer. This strategic roadmap guides statewide cancer control efforts focusing on four areas: primary prevention, early detection, treatment, and survivorship. The 2021-2022 report, using 2017 numbers, found that approximately two in five Indiana residents now living will eventually have cancer.

The report identifies these barriers as contributing to cancer health disparities in Indiana:

- Poverty (the most significant contributing factor)

- Lack of health insurance or a personal doctor or health provider

- Socioeconomic status (income, education)

- Cultural values or beliefs regarding healthcare

- Discrimination and social inequities like communication barriers

- Geographic location, including travel distance and transportation access to care

All these factors mirror telling national trends, that rural communities across the country are fighting the cancer battle on multiple fronts with fewer armaments than those in urban areas.

These factors also limit rural residents’ health literacy and healthcare-seeking behaviors, two aspects that directly relate to cancer prevention. Getting people to understand these issues is complicated and sometimes tricky. For instance, Lungcancer.net asked 800 people living with lung cancer about life after diagnosis. They found that while most people were familiar with general cancer terminology, any terminology more specific to their diagnosis could be confusing. They also found that only 44 percent of people with lung cancer sought out a second opinion. Treatments today for lung cancer are more diverse, and, therefore, awareness of treatments specific to lung cancer (like biomarker testing — a way to look at genes, proteins, and other substances to provide information on cancer) was lower.

The Ten Leading Causes of Death: All Age Groups, Indiana Residents. Indiana Mortality Report, 2017, Table 3-1. Age-adjusted rates are per 100,000 population. Source: Indiana State Department of Health, Epidemiology Resource Center, Data Analysis Team.

According to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, to understand cancer and its treatments, people must exercise their health literacy quotient. Health literacy is the degree to which people find, use, and understand information to evaluate their healthcare. Nowadays, more often than not, it requires access to a computer and broadband access to the internet.

Indiana ranks 21st in broadband availability, with more than 600,000 Hoosiers currently without access, according to Broadband Now. In a study conducted by Microsoft, only 16 percent of all households in Orange and Washington counties have broadband access. In Lawrence County, only 17 percent of households have access, whereas 36 percent of Monroe County households have access. All of this despite Indiana investing over $100 million in broadband expansion. For residents in rural areas, the question becomes how can they raise their health literacy quotient if they can’t access the information. Or even how to secure a team of healthcare experts who can guide them through the complex maze of cancer.

Navigating cancer

Cancer nurse navigators are the sherpas of cancer’s Everest. One such person is Stephanie Grubb, an oncology nurse navigator for IU Health in Bloomington. She has been in oncology nursing for eleven and a half years. As a nurse navigator, she works closely with cancer patients to help them traverse diagnosis, treatment, and care. Her job is to break down the barriers to care. Grubb clarifies and explains cancer and treatment information. She translates insurance coverage issues. She helps find supplies. For patients going through treatment, she is there to help them along. She’s even in the pre-op room before they go into surgery.

Stephanie Grubb, an oncology nurse navigator for IU Health in Bloomington, works closely with cancer patients to help them traverse diagnosis, treatment, and other resources. | Courtesy photo

“I want to make sure that my patients have the resources and support to make it as easy as possible for them,” Grubb says.

Health literacy is one of the challenges she has faced. “A lot of rural people need more education to understand the medical terms that we throw at them, so we have a good one-to-one conversation to make sure that they fully understand what is being told to them and what their treatment might entail,” she says.

But according to Mead at the Lohano Center for Advanced Medicine, some patients don’t want that information when it comes to their cancer. In her 27 years of experience, she has seen cancer fatalism creep into how her patients make their health decisions. Cancer fatalism is a belief that external forces control a person’s cancer outlook, that no matter what they do, the outcome is beyond their control.

“I have had ladies say to me, ‘I haven’t had a mammogram, and I don’t plan on getting one because the Good Lord has taken care of me all this time, and whatever comes, I will deal with it,’” she says. She has had other patients tell her, “This is going to kill me anyway, so why do the treatment?” Some people don’t make their health a priority even though they know that they should and can, she says. As a result, they may not seek out cancer screenings or even treatment.

One reason that cancer rates are declining is because cancer screening opportunities like mammograms, colonoscopies, or even regular wellness checkups combat cancer, often catching cancer early. Failing to get a screening may result in advanced-stage disease, and rural residents are less likely to get these screenings. According to the CDC, breast cancer has the highest treatment costs than any other cancer. The report also indicates that for a typical woman with employer-sponsored insurance coverage who is diagnosed with early-onset breast cancer can expect to shell out $5,800 (including premiums). But with cancer screenings like mammography, studies show that screening every two years will reduce breast cancer deaths by 26 percent for every 1,000 women screened.

Not only will screenings reduce deaths, but they also decrease the number to 29 percent of women diagnosed with advanced stage disease that has metastasized to other parts of the body. The CDC’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program provides funding to low income, uninsured, and underinsured patients for breast and cervical cancer screening. Nurse navigators like Mead often tackle these problems too.

No doubt about it: Cancer treatment is expensive. The American Cancer Society found that in 2018, U.S. cancer patients paid $5.6 billion in out-of-pocket expenses for cancer treatments. Factors that contribute to cancer costs are dictated by the type of insurance and its limits, geographic locations, and drug and treatment plans and settings. The National Cancer Institute estimates that cancer costs are projected to increase to $246 billion by 2030, a 34 percent rise based only on population growth and aging. Because a substantial number of cancers can be prevented through early screening, the Affordable Care Act requires most private insurers and Medicare to cover the cost of screenings.

But screenings not only decrease cancer costs, they also save lives. A 2019 Journal of Clinical Oncology review of cost effectiveness of breast cancer and prevention found that “investments in prevention, screening, and treatment have together reduced cancer mortality by 27 percent over the last quarter of a century.”

Travel for treatment

In recent years, access to these screenings has become easier with mobile screening units for cancer. But if rural residents do not have mobile screening availability, their only option is to travel. Travel for screenings. Travel for tests. Travel for treatment. Sometimes, travel and everything that comes with it, like gas money, transportation, time off of work, and even drivers, are the biggest obstacles stopping the cancer patient from getting screenings or treatment.

Recently, the goal of local providers has been to move care and support services closer to the patient — by consolidating cancer care services in Bloomington to the new IU Health Hospital and the opening of the new Cancer Support Community South Central Indiana (CSC-SCI).

Cancer Support Community South Central Indiana, 1719 W. 3rd St. in Bloomington, offers free programming for those with needs beyond clinical care: wellness classes, art therapy, individual counseling, patient and family support groups, transportation assistance, and more. | Photo by Limestone Post.

The opening of a south-central Indiana branch of Cancer Support Community resulted from a four-year conversation between the Bloomington Health Foundation, Indianapolis’ Cancer Support Community, and IU Health. After the discussion, says Eric Richards, CEO of Cancer Support Community Central Indiana, “it became very clear that we could be a conduit to accomplish the goals that the Bloomington Health Foundation and the community wanted to attain, which was to expand on IU Health’s work through the Olcott Center on complementary services and broaden those services offered in the region.”

With a $20,000 grant from the Bloomington Health Foundation (BHF) to support virtual programming during the pandemic, CSC-SCI started its operations. Covering an eleven-county range in southern Indiana, it provides complementary cancer support services like support groups, wellness programs, survivorship assistance, and other programs to the Bloomington and south-central Indiana areas.

A subsequent $260,000 startup grant from BHF in July 2020 funded CSC-SCI for a year and will create in-person programming at 1719 W. 3rd St. in Bloomington. An additional $1.2 million, five-year grant will fund the physical location, staff, and programs for CSC-SCI, says Heather Robinson, chief operating officer of BHF. It’s a significant move, says Robinson, that magnifies BHF’s history of funding cancer care through the Hoosiers Outrun Cancer event, which has been funding community cancer services since 2000. In 2021, Bloomington Health Foundation licensed Hoosiers Outrun Cancer to CSC-SCI.

But like any healthcare system throughout the U.S., funding cancer care is a big need, especially in Monroe and surrounding counties, says Michelle Gilchrist, CEO of Bloomington Health Foundation. If nonprofits and volunteers in a community are not able to help with cancer support services, then rural hospitals often must pick up that slack. And with the continuing closing of rural hospitals, this becomes tricky.

Michelle Gilchrist, CEO of Bloomington Health Foundation | Courtesy photo

Shifting of Cancer Care Services in Monroe County

So how does a community like Bloomington and its surrounding counties face this big need while still trying to remain local care providers? It’s one of the biggest challenges that BHF faces as a foundation, Gilchrist says. That is why the BHF has partnered with Cancer Support Community. “We are committed to improving cancer care in our community, including the south-central region,” says Gilchrist. “One way that we can do that is to invest a million-plus dollars to get the right organization here to deliver the right kind of high-quality services.” Gilchrist joined Bloomington Health Foundation in September 2021 after spending the previous five years as CEO of the National Foundation for Transplants.

Bloomington Health Foundation has been a critical partner in transitioning these cancer-care services from the Olcott Center to CSC-SCI, says Richards. The Olcott Center is now closed, and by this summer its staff will complete the transition of its nurse navigation teams to the new Bloomington IU Hospital, with its complementary services going to CSC-SCI.

“IU can now focus on nurse navigation, and we are handling the complementary services,” Richards says, adding that the complementary services go hand in hand with traditional cancer treatments. “Quality of life and mental health is critical for good cancer outcomes,” he says.

Previously an oncology social worker, Katie Tremel is now the program manager for CSC-SCI. For Tremel, the recent shift in services has been smooth. “The Olcott Center staff provided patient referrals and were great with follow-up to any questions I may have had,” says Tremel. She’s also cultivating relationships with regional infusion centers (where patients receive chemotherapy) and oncology practices while working with IU Health’s nurse navigation teams.

Tremel has found that many rural patients face obstacles when seeking care. Things like illness, lack of family and friend support, or declining services in nearby counties impact cancer patients’ care in rural areas. But the biggest hurdle that CSC-SCI patients face is transportation, says Tremel. Patients outside of Bedford, Martinsville, and Bloomington must travel to get infusion and radiology services. “So, if they live in Mitchell, they have to drive to Bedford,” says Tremel.

But what if you don’t have the money, car, gas, or driver to travel to another town for your treatment? Fortunately, for people who live in Lawrence County, they can call upon the all-volunteer organization Lawrence County Cancer Patient Services.

Volunteer Supported Cancer Services

Created in 1994 with a single anonymous donation, Lawrence County Cancer Patient Services (LCCPS) helps 160 to 190 Lawrence County cancer patients a year by providing transportation help, food money, and even cancer support items like seat belt buddies that protect a cancer patient’s chemotherapy port site when driving. Teena Ligman, a cancer survivor herself, is the patient coordinator. She is in charge of breaking down cancer treatment barriers in Lawrence County and coordinating with local health providers and other cancer patient services like CSC-SCI in Bloomington.

With forty volunteers and a board of directors, LCCPS raises money to help Lawrence County cancer patients get their treatment. “Gas cards are one of the biggest things that we do,” says Ligman. Recently she received a call from one of her patients who needed a gas card to get to her doctor in Hamilton County the very next morning so she could find out if her cancer had spread. When Ligman learned that the mail hadn’t yet delivered the patient’s card, Ligman got in her car and drove the gas card to her.

This patient was lucky. She had a family to make the drive with her. But if she didn’t, Ligman would have found her a driver like she’s done for countless others. “I think that no one should have to face really bad things alone,” says Ligman. “Some people have no choice because they don’t have a family. So, we try to find a team for them.”

With forty volunteers, Lawrence County Cancer Patient Services (LCCPS) helps up to 190 Lawrence County cancer patients a year by providing transportation help, food money, and cancer support items. Teena Ligman, the patient coordinator, says LCCPS hosts annual Celebration of Life luncheons, like the one above, with their patients. | Courtesy photo

According to Ligman, cancer care in a rural area is a matter of coordinating services. An infusion center may be located in a neighboring county, and the patient’s doctor may be located in Bloomington or even Indianapolis, so they need a hotel room for an overnight stay. Or a patient may need nutritional supplements like Ensure or Boost to keep their strength up during treatment. “Many of the specialists are in larger cities,” says Ligman. “Many people don’t have either funding with lower income or confidence or ability to see a specialist in a large city, which requires a long drive and an overnight stay if it wasn’t for our group helping them.”

As a former cancer survivor, Wilma Sage at Orange County Cancer Patient Services found out about LCCPS while working as an oncology nurse in Bloomington and Bedford. As a resident of Orange County, she knew Orange County didn’t have the same services but needed them. “I just felt like someone should start one in Orange County,” says Sage.

So after enlisting the help of her aunt and a friend, they all agreed to give it a try. Since July 2019, they have helped up to 100 Orange County residents get their cancer treatment by providing similar services to their residents.

“We cover Paoli, Orleans, French Lick, and other small towns in Orange County,” says Sage.“We offer gas cards and give them to patients to help them get to their appointments. We donate wigs after chemotherapy and prostheses and bras after surgery. We also give food cards and medical supplies, some of which are donated.”

“Cancer patients appreciate what you do for them,” says Sage. “We have lost a lot of family and friends who have had cancer and seen what they have gone through. I feel that we made a difference in that area.”

Tremel is not aware of similar cancer-patient-services programs outside of Lawrence and Orange counties. While volunteers such as Ligman and Sage have stepped up and created these services to help their county residents, cancer patients are not so lucky in other counties.

One reason is that volunteers run these organizations. So, no volunteers, no organizations like those in Lawrence or Orange counties. Sharon Mead knows this well. She tried to develop such an organization in Daviess County, but people didn’t show up. So, Daviess County relies on the American Cancer Society for online support chats and groups and wellness advice. That’s why future growth plans of CSC-SCI may include sublocations in communities throughout the region, says Richards of Cancer Support Community Indiana. “I would love to see four centers throughout the region similar to what we have currently in five years from now,” Richards says.

IU Health Cancer Services

With a presence in south-central Indiana, IU Health meets cancer diagnosis and treatment needs with chemotherapy infusion and radiology centers in Bedford, Bloomington, Martinsville, and Paoli. Ted Jackson is the service line administrator for IU Health Southern Indiana Physicians Hematology/Oncology and Radiation Oncology. While based in Bloomington, he serves as the administrator with all the providers in oncology and other specialty areas, along with Dr. Mohan Shenoy. Jackson meets weekly with managers of each facility to address cancer care in these facilities.

Ted Jackson, service line administrator for IU Health Southern Indiana Physicians Hematology/Oncology and Radiation Oncology | Courtesy photo

One of their main focuses is making sure that they take care of patients closer to home. For instance, “We might have a Paoli patient who is receiving chemo treatments at Bedford,” Jackson says. “But while you are doing those treatments and need hydration, that patient doesn’t need to go to Bedford for IV hydration. They can go to the infusion center at Paoli for hydration.

“I had a patient who was being treated in Bloomington,” Jackson says. “It was her birthday, and she had a number of doctors’ appointments, so she was driving back and forth from Bedford to Bloomington. When I told her that she could get her infusion in Bedford, where she lived, and still keep her doctor in Bloomington, she started crying,” because now she could spend more time with her grandchildren.

Oncology patients are often concerned about the concept of time. Will I have enough time with family? With friends? “We have a better understanding of what ‘systemness’ means, “says Jackson. “We are really trying to concentrate on patient-designed care.”

The new IU Health Bloomington Hospital opened on December 5, 2021, at 2651 E. Discovery Pkwy., just off of the State Road 45/46 Bypass. Previously, cancer care services were scattered in various locations in Bloomington. But with the new hospital, the long-term plan is to have all of their cancer services provided on the Bloomington campus while still maintaining oncology, infusion, and radiation services in Bedford, Paoli, and Martinsville. “Being able to have a succinct, efficient, multidisciplinary approach in one location is a great goal for that campus,” says Jackson.

The Olcott Center’s former nurse navigator program is now part of the new IU Hospital, Jackson says. “We are moving the nurse navigators who handle breast cancer to be closer to their patients. We will also move our other nurse navigators to have them in the infusion center and our oncology clinic.” Nurse navigators will serve as a conduit and advocate for bridge-support services like those offered at CSC-SCI, says Jackson. By summer 2022, the nurse navigator program will be situated at IU Bloomington Hospital.

One of the most challenging aspects of cancer care in rural areas is ensuring that wellness programs and screenings are available. IU hopes to provide added coverage in those areas with hematology and oncology physicians in the coming months, Jackson says.

“I think that moving forward, we will see more direct collaboration with primary care physicians within Southern Indiana Physicians and even outside of it to share capabilities, capacities, and make connections, so patients are aware,” Jackson says. “I recently talked to someone, a 40-year-old, who had a colon cancer risk. They had a colonoscopy, and they found a low stage cancer. He was able to get it taken care of right away.”

Connecting primary care providers with specialists

Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) is a program that connects teams of interdisciplinary specialists with primary care teams. As a way to elevate cancer care in Indiana, the Cancer Prevention and Survivorship ECHO program at Indiana University boosts the knowledge of oncology teams, healthcare providers, and rural primary care physicians who have cancer care questions.

Project ECHO is like having an encyclopedia of experts at one’s fingertips. Operating as a virtual lecture and case management vehicle, physicians and other healthcare providers meet virtually with oncology experts within the Indiana University and IU Health arenas.

The new IU Health Bloomington Hospital opened in December on the northeast side of town. The long-term plan is to have all cancer services provided on the Bloomington campus while still maintaining oncology, infusion, and radiation services in Bedford, Paoli, and Martinsville. | Photo by Limestone Post

Using a hub and spoke model, the Cancer Prevention and Survivorship ECHO includes oncologists, social workers, Indiana State Department of Health representatives, and other folks who look at the cancer continuum from different angles. These represent the hub. The spokes are are rural physicians and providers looking to better manage cancer care for their patients. The two groups come together in an all-teach and all-learn manner.

“For providers trained by ECHO, they are trained to look at the cancer continuum, and if they have a question about the patient, they can bring it to the Cancer ECHO to learn how to deal with a particular issue to decide whether they can deal with it locally or not,” says Andrea Janota, interim director of the Center for Public Health Practice and the IUPUI ECHO Center.

Since those who have survived cancer face a unique set of healthcare needs, the Cancer ECHO is now identifying those needs and creating best practices for them. The key, says Tyler Severance, an IU Health pediatric oncologist, is helping physicians and providers identify the problem. “We think of cancer as a continuum that includes preventing cancer, which is something as simple as getting a vaccine, using sunscreen, and screening tests,” says Severance.

These screenings aid early detection, better treatments, better supportive care, and long-term surveillance, all of which help increase the survivorship rate of cancer. The American Cancer Society’s Annual Cancer Facts 2020 found that the five-year cancer survivor rate has risen from 39 percent to 70 percent since the 1960s.

According to Cancer.gov, as of 2019 (the year for which the most recent data is available), 16.9 million cancer survivors were living in the U.S. Severance and his Cancer Project ECHO team recognize that survivorship is a critical aspect of the post-treatment cancer care continuum, saying that they are just beginning to scratch the surface of what patients and their families are going through. But what is survivorship?

Life expectancy is growing

Cancer.net says, “Cancer survivorship has two common meanings: having no signs of cancer after finishing treatment and living with, through, and beyond cancer.” A person gets cancer and gets treated. Cancer goes away. Then the patient waits. But imagine that wait. Will it come back? Will it be worse? When will it come back?

Sharon Mead knows those feelings well. A recent scare reminded her all over again of the fear of cancer. For every cancer survivor, survivorship is a time of waiting and wondering.

As CSC-SCI’s Tremel says, “Someone diagnosed with cancer can tell you that who they were before and who they are after is not the same,” she says. “Survivorship is hard. You may have had cancer and beat cancer, but you are always a survivor and living with what it is.”

Still, survivorship requires a long-term plan.

“I think that there is a sense that once cancer is cured, you are in remission, there is a sense that you have won,” says Severance. Providers now are recognizing there is more to it. Many people cope with the emotional aspects of cancer and the aftereffects of cancer treatments. Cancer treatments like radiology, chemotherapy, and others may have long-term impacts. Breast cancer survivors often seek even multiple breast-reconstruction surgeries when treatment finalizes.

While cancer survivorship may be the last piece of the cancer continuum, says Severance, “survivorship starts at diagnosis. It’s a team-based approach.” It’s a care continuum that needs an army to defeat even after the cancer is gone. In fact, according to Richards, CSC-SCI serves more survivors than active cancer patients since most active cancer patients are focused on their treatment. With specially tailored programming, they reach survivors, their families, caregivers, and even kids of survivors.

So, while cancer may not necessarily be a death sentence, says Ligman, it doesn’t have to ruin your life. Cancer screenings and treatments are improving. Nurse navigators and cancer support services fight cancer stressors. Life expectancy among cancer survivors is growing. While rural residents by virtue of their circumstances and surroundings may, at times, be at a disadvantage, their survival chances increase in Bloomington and south-central Indiana.

[Editor’s note: The ribbon cutting for the new Cancer Support Community South Central Indiana will be from 1 to 4 p.m. on Tuesday, March 29, at 1719 W. 3rd St. in Bloomington. Visitors can tour the new building, meet the staff, and learn about the free programs of support for those facing cancer.]

The Bloomington Health Foundation is an underwriting partner of Limestone Post. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs in Bloomington and neighboring communities.

The Bloomington Health Foundation is an underwriting partner of Limestone Post. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs in Bloomington and neighboring communities.

Hoosiers Outrun Cancer

For the past twenty years, Hoosiers have been running to fund cancer care services in Bloomington and southern Indiana. The 5K event, Hoosiers Outrun Cancer, was the brainchild of Karen Knight and Dorothy Ellis. One evening twenty years ago, they were walking, trying to figure out how they could help a friend who had been recently diagnosed with cancer. So they created a 5K race to raise funds for cancer services. Rumor has it that IU coach Bob Knight actually named the event Hoosiers Outrun Cancer.

For the past twenty years, Hoosiers have been running to fund cancer care services in Bloomington and southern Indiana. The 5K event, Hoosiers Outrun Cancer, was the brainchild of Karen Knight and Dorothy Ellis. One evening twenty years ago, they were walking, trying to figure out how they could help a friend who had been recently diagnosed with cancer. So they created a 5K race to raise funds for cancer services. Rumor has it that IU coach Bob Knight actually named the event Hoosiers Outrun Cancer.

Since then, the race has morphed into a significant fundraiser for the Bloomington Health Foundation, raising more than $280,000 in 2021 with all donations going toward cancer support services in Bloomington and south-central Indiana. In 2021, they licensed the race to the new Cancer Support Community South Central Indiana, located at 1719 W. 3rd St. CSC-SCI provides complementary cancer support services like wellness programs, support groups, yoga, cooking, and other programming, some of which are virtual.

The annual event often has more than 5,000 attendees and 100 individual and business partners. It presents several team awards and offers a 1-Mile Kids Fun Run/Walk event. This year it will be held on September 24, 2022, at IU Memorial Stadium. Virtual options will be available. For more information, check out hoosiersoutruncancer.org.

—Rebecca Hill