“I’m a Midwestern gal.”

That’s Zaineb Istrabadi speaking, not some corn-fed, flaxen-haired, small-town prom queen. Istrabadi came to that conclusion after spending some 14 years working and living in New York City. She was born in London, England. Grew up in Baghdad, Iraq. She speaks five languages. In one of those languages, the word for God is “Allah.”

She’s the apotheosis of the self-congratulatory moniker we used to hang upon ourselves, we Americans: This, our elementary-school civics teachers proudly told us, is the melting pot.

Make no mistake: Zaineb Istrabadi is, most assuredly, a Midwestern gal. But, like almost every ethnic or alternately hued émigré to this country, she’s encountered her share of people who wish she’d go back to wherever she came from.

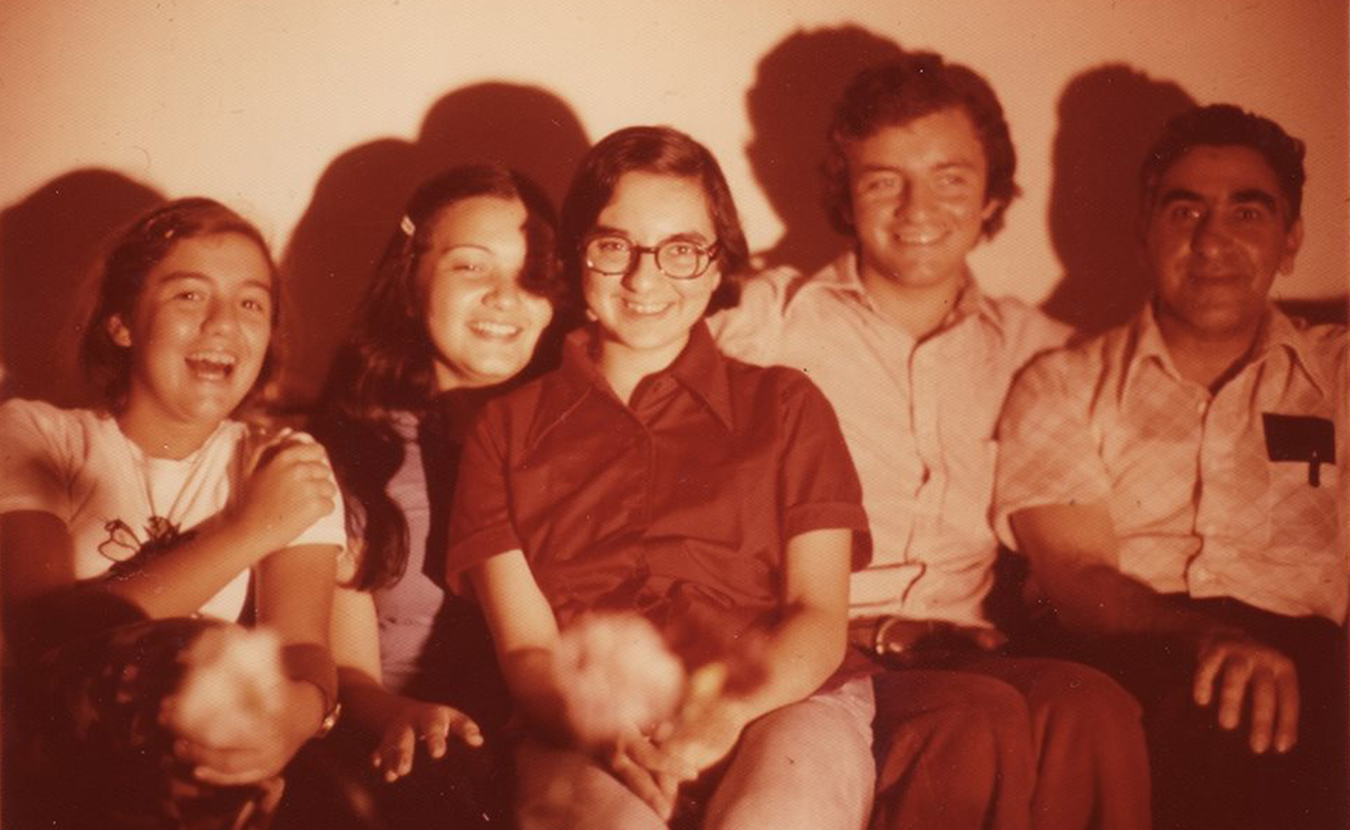

Zaineb, center, with her brother, Feisal, and their mother, Amel Amin-Zaki, at BLU Boy Café & Cakery a few years ago. | Courtesy photo

Zaineb Istrabadi comes from one of Bloomington’s most storied families. Her father, Rasoul Istrabadi, was the city’s first municipal engineer, hired in 1972 when the new mayor, Frank McCloskey, and an upstart Democratic city council pledged to professionalize city services and departments. Zaineb’s brother, Feisal, is a respected professor of practice at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law, as well as director of the Center for the Study of the Middle East. Her mother, Amel Amin-Zaki, was a Shakespearean scholar who studied at a couple of other bastions of Midwestern academia, the universities of Wisconsin and Michigan. Now, Zaineb has settled in as a longtime teacher of the Arabic language as a senior lecturer in IU’s Department of Near Eastern Languages & Cultures, and she gives presentations to schoolchildren and civic groups about the Arab world and Islam.

She is, I suggest, a woman of the world.

“Perhaps, yes,” she says. “I certainly would like to think so. We’re all human beings. Our blood is red. I don’t care about the superficiality of skin color. And I like to treat people the way I like to be treated, namely with respect.”

Her parents were both ethnic Iraqis. Iraq, of course, is an Arabic-speaking country although other languages are spoken there. Before sitting down to interview Istrabadi, I asked a number of friends, “What is an Arab?” None could say with any level of precision.

“We have a hard time saying as well,” Istrabadi says. “The most basic response is: An Arab is anyone who says they are an Arab. For some, an Arab is somebody who is of Arab blood. In other words, they can trace their ancestry back to some Arab tribe. I can’t do that, for example, but I consider myself an Arab. I speak Arabic. I dream in Arabic. I swoon to Arabic music and songs. Some Arabic poetry makes me weep in a way that English or French poetry doesn’t. I’m culturally an Arab but actually I’m a mongrel. I know for a fact that I’m part Kurdish, I’m part Turkman, and there are a couple of drops of Arab blood. Who knows, maybe there’s Greek in me. After all, Alexander the Great went though the area.

“The bottom line for me is it’s a cultural thing, not a national thing. I was born in England. I have a British passport, so I am one of Her Majesty’s loyal subjects as well.

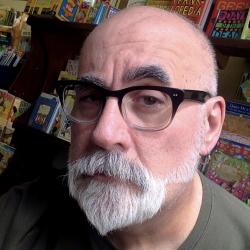

Istrabadi, pictured here driving friends, is a longtime teacher of the Arabic language as a senior lecturer in IU’s Department of Near Eastern Languages & Cultures. | Courtesy photo

“I’m an anglophile. I went to a British school when I was in Baghdad. After I was taught the existence of God, I was taught about Shakespeare.

“I’m originally Iraqi but I’m also American.”

The melting pot.

That didn’t matter when, four and a half years ago, Istrabadi received a couple of startling messages from her bank. She and her mother (whom Zaineb was taking care of following a debilitating stroke) had been customers of the same bank through several changes of ownership. By 2014, it was owned by one of the four biggest banking corporations in America. That summer she got a phone call from Chase Bank.

“They said that our business was no longer welcome,” Istrabadi explains. The call was followed up by a letter from a Chase regional office, telling her the same thing. Istrabadi phoned Chase’s local branch manager as well as the regional office. “I kept asking, ‘What have we done?’ Nobody could tell me what the problem was. And then it finally came to me that it was because of our background. My brother also had been kicked out of Chase. And then we discovered that many of us, friends in Michigan and New York and elsewhere, had also been kicked out of Chase.

In 2014, Istrabadi and other members of her family were told by Chase Bank that they could no longer bank there. She says, “I think about it every time I drive by a Chase.”| Courtesy photo

“I’m pretty loyal. I always go to the same grocery store. I get gas at the same station, et cetera. I told the bank manager — it wasn’t his fault — ‘I feel like I’ve been on a boat called America for 44 years and somebody grabbed me and threw me overboard.’ And I was weeping.”

I wrote about the incident on my blog, The Electron Pencil. I called a Chase spokesperson for an explanation. That person told me Zaineb was “a politically exposed person, according to our regulators.” Since her brother Feisal had worked for the Iraqi government — he served as Iraq’s ambassador to the United Nations following the fall of Saddam Hussein — he and she would be considered risky customers, according Chase’s interpretation of the federal regulations it operates under. It wouldn’t be worth Chase’s trouble to make sure they weren’t funneling their money into causes or organizations that might be harmful to America.

“And they come and tell me this in 2014?” Istrabadi asks. “Am I supposed to put my money in a mattress?”

She didn’t have to resort to that. In fact, the local Chase branch manager apologetically offered her a tip. “I was sent by the manager of Chase to Fifth/Third Bank and was greeted there as if I were a queen. That, of course, made me cry as well,” Istrabadi says.

Nevertheless, the incident sticks with her. “I think about it,” Istrabadi says, “every time I drive by a Chase.”

Istrabadi experienced early preparation for discrimination. She was part of the first graduating class of Bloomington High School North. Before that campus opened, she attended what’s now called BHS South.

“The first semester when I was at South,” she says, “I stepped off the bus and I got spat upon while being called a ‘dirty AY-rab.’” The student who spat on her was a classmate, and “he was going to be on the bus with me twice a day, going to school and then returning home. I think he did it on a dare. I just went inside and washed my face.

“Talk about being terrorized! For the rest of the year, I never knew when he might do that again.”

What gives her the resilience to go on after such indignities? Istrabadi says she loves people, especially her IU students who, in fact, voted her the Student Choice Award for Outstanding Faculty Member in 2005. “I love them,” she says. “I never got married so I never had any children. I see my students in class four times a week. They become members of my extended family. I really care about them — not just what they do in my class but I care about their well-being and insist that I’m not there just to teach them Arabic but to help them through their college years.”

Could it be her faith that helps her survive and forgive? The tenets of Islam, to be sure, help her nurture those qualities in herself. But another faith helps as well.

Istrabadi, center in glasses, attending Bloomington’s Resistanbul at Sample Gates. | Courtesy photo

“I was reading The Cloister Walk by Kathleen Norris,” Istrabadi says. “She is affiliated with the Dominican Order [of the Roman Catholic Church]. She has not taken vows, but, when she needs to get away and get centered, she goes to the monastery. The Dominicans treat anyone who walks into their monastery as if it is the person of Jesus Christ. I found that deeply touching. Actually, I’m getting goosebumps as I say this. So I try to practice this with everyone.”

I remind Istrabadi of Jesus Christ’s words: Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of my brothers, you did for me. She nods vigorously. Then we toss around the idea that the line would be amended today to include sisters, transgender people, and so many others.

“Human beings,” Istrabadi says. “I also extend it to animals. Whereas in the old days I might have killed a mouse, now I try to catch it and take it outside. I do it consciously because we’re supposed to be kind to animals as well.”

She laughs. “I do have trouble with spiders, though, but I’m trying to be kind to them as well.”

I tell her she has love in her heart.

“I hope so,” she says. “Ultimately, it’s the only thing that lasts.”

***

Zaineb Istrabadi lived a lot of life before she wound up in Bloomington as a teenager.

“Most of us living in exile, most of the Iraqis living abroad, have a reason for living abroad — to save our lives,” she says. “My parents, had they stayed in Iraq, at best they would have been jailed because they refused to join the Ba’ath party. They were invited to and they said, ‘No, thank you. We are not involved in politics.’ The attitude of the Ba’ath party was if you’re not with us, you’re against us.”

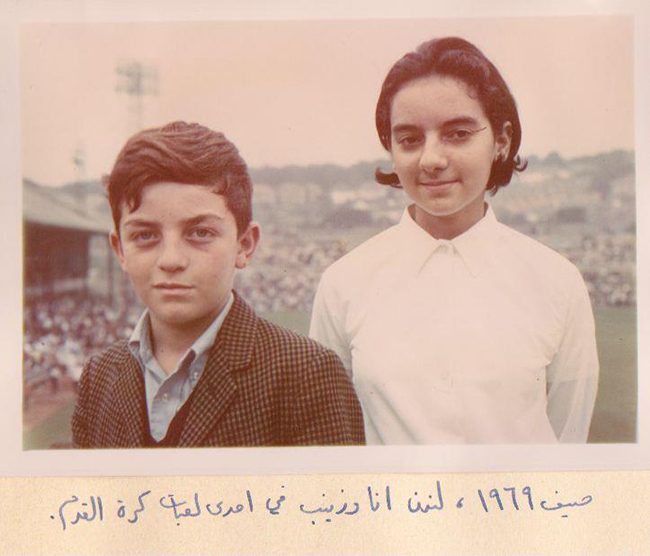

Istrabadi (right) with her cousin Omar Al-Farouk Salem Al Damluji at a Manchester United v. Crystal Palace soccer match in 1969. | Courtesy photo

Rasoul Istrabadi and Amel Amin-Zaki left their native Iraq to study in the United States. Rasoul had studied engineering at the University of Baghdad and came to the U.S. to continue his studies at Louisiana State University on a Fulbright scholarship. Amel was also awarded a Fulbright, earning her master’s degree at the University of Wisconsin. She went on to study at Michigan, where she met Rasoul. The two married in Ann Arbor, then returned to Iraq. The Ba’athists had taken over Iraq for good in 1968, eleven years before the party gave rise to Hussein. The Istrabadis got out while the getting was good.

“We came here and settled in Bloomington in 1970. My mother wanted to get her Ph.D., so we came here to IU,” Zaineb says.

After graduating high school, Zaineb studied biology at IU. “Every parent wants their son or daughter to become a doctor,” she says, laughing. “I had done very well in the sciences in high school. Then they got a little harder at IU. In organic chemistry, it became clear I couldn’t memorize things. Fate indicated to me that I would wind up killing my patients if I became a doctor.

“Then came the realization that I always loved the humanities.”

She went on to earn her Ph.D. in Near Eastern languages and cultures, writing her dissertation on The Principles of Sufism.

She moved to New York in 1986 to work as the research and administrative coordinator for the noted public intellectual and Columbia University professor Edward Said.

“He was a renaissance man,” she says. “He knew about English literature and Arabic literature — because he was a Palestinian. He was a cultural critic, a literary critic, a music critic. He tried to open my ears and my mind to Wagner but I absolutely refused. I don’t care for Wagner and, regretfully, my brother is now into him.” She laughs.

“In fact, there was a three-day conference about Wagner at the Columbia campus [in 1995],” she continues. “Dr. Said and Daniel Barenboim [the noted pianist and conductor] put it together. It was marvelous, just amazing.”

Istrabadi was still working for Said at the time. As time went by, she was becoming more and more disgusted with the situation in Iraq. “The Arab student organization [at Columbia] invited the Iraqi ambassador to the United Nations to speak. In other words, the Ba’athist representative, representing Saddam’s government! I was so outraged…, well, I raised Cain. I made phone calls and emails and the organization came back and said, ‘If you can find somebody at this late date to have a debate with him, we would accept that.’ So I called my brother, and said, ‘Do you want to do it?’ He was practicing law at the time in northern Indiana.”

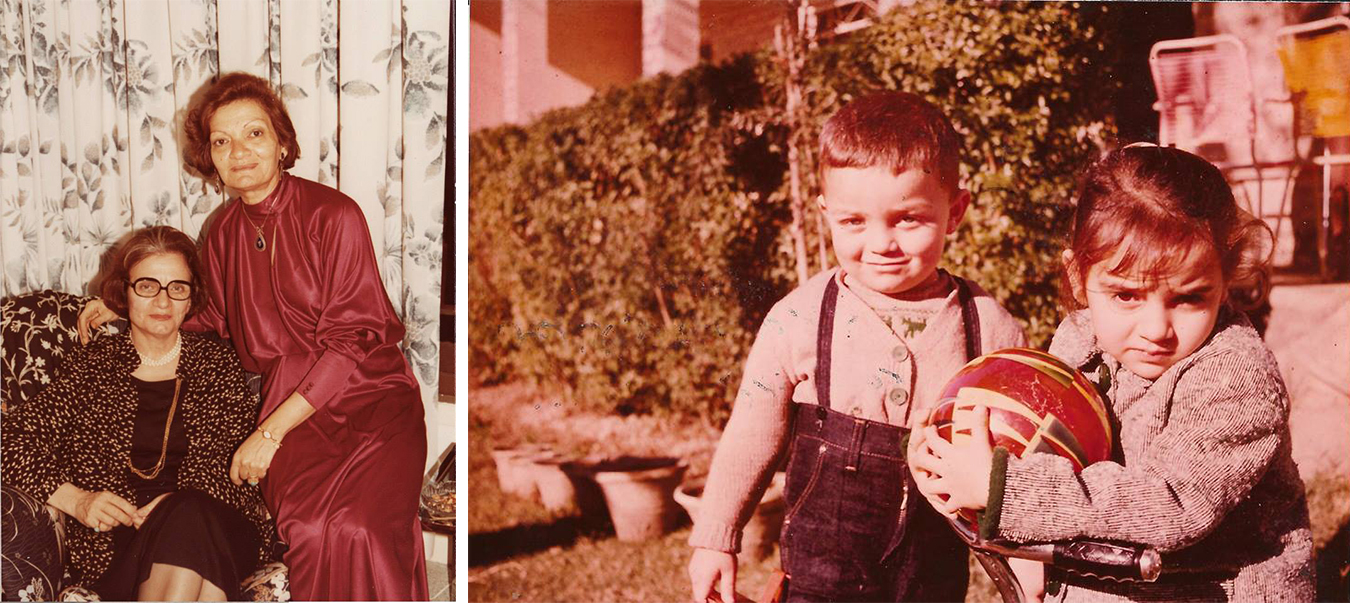

(left) Istrabadi’s mother, Dr. Amel Amin-Zaki, right, and Amel’s sister, Dr. Laman Amin-Zaki, in Abu Dhabi, 1979. (right) Zaineb and her cousin Omar in 1959. | Courtesy photos

Feisal agreed to the debate. Zaineb’s entreaty and Feisal’s decision had implications: “My mother blamed me for getting him involved in the opposition [to the Hussein regime],” she says. The elder Istrabadis had assiduously avoided confrontation, and now their son was throwing himself into the fray. “It was a risk to his life and to others involved in it,” Zaineb says.

After Saddam’s fall, Feisal himself would go on to become the new Iraq’s ambassador to the UN. He also helped write the country’s new constitution, concentrating on civil and human rights.

Amel Amin-Zaki suffered a debilitating stroke soon after the millennium turned. Zaineb came home to take care of her (Rasoul died in 2006; Amel would die in 2016). “I came back to Bloomington in 2001, in May,” she says.

“I was wondering what I was going to be doing, and then 9/11 happened. Frankly, it’s thanks to 9/11 that IU needed somebody extra in the Near Eastern Languages and Cultures Department. So I came aboard in October of 2001.”

She’s been teaching Arabic here ever since. Zaineb especially likes teaching the introductory course to the language. She’s been involved with countless organizations for Islamic-American amity. She sat on the city’s Diversity Committee and was the faculty advisor to IU’s Muslim Student Union.

The lover of Arabic poetry has herself penned a couple of published verses in the Arabic-American English-language magazine Al Jadid (The New). One is entitled “Whither I Turn.”

Her life has taken many turns, but now it seems unlikely she’ll ever turn away from Bloomington and America.

“This is my home,” she says. “I’m a Baghdadi Hoosier.”

[Editor’s note: Michael G. Glab’s full interview with Zaineb Istrabadi can be heard today on his radio show, Big Talk, which runs on WFHB (91.3 FM, 98.1 Bloomington, 100.7 Nashville, 106.3 Ellettsville) every Thursday at 5:30 p.m. and will be available, along with podcasts of past shows, at WFHB.org. Each of Glab’s monthly profiles for Limestone Post is based on one of his Big Talk interviews and will be posted on the same day that the interview airs on Big Talk.]