Hoagy Carmichael holds son Hoagy Bix in the early 1940s. More recently, Hoagy Bix was in town for IU Theatre’s production of “Stardust Road: A Hoagy Carmichael Musical Journey,” and he talked with writer Michael G. Glab about growing up in Hollywood, his famous namesakes (Hoagy and Bix), and the musical that is premiering in Bloomington. | HC Series 3, Box 3, item 33. Hoagy Carmichael Collection, Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University

Try as he might, Hoagy Bix Carmichael cannot escape the music that you have to imagine is encoded in his genes.

Despite being deeply involved in preserving and presenting his famous father’s unforgettable songs for the last 30 or so years, Hoagy Bix has never felt the need to be like his father or to try to replicate the success that, for decades, made Bloomington’s own Hoagland Howard “Hoagy” Carmichael a household name.

For Hoagy Bix, Hoagy pere’s eldest child, that would have been a proposition doomed to failure.

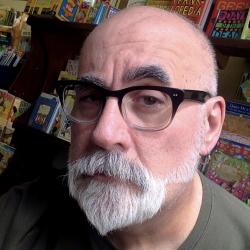

Mention a song or recall an historical event from the 1920s to the 1960s — when Hoagy was one of the big names in show business — and Hoagy Bix just might begin singing.

Named for his father and Bix Beiderbecke, Hoagy’s pal and mentor who died too soon, Hoagy Bix happens to mention the TV western Laramie, in which his dad appeared as “Jonesy” toward the end of his illustrious career. Naturally, a song line ensues:

Marry me, marry me in Laramie.

This was from a song the elder Hoagy wrote for and performed in the show back in its first season, 1959-60.

If a person has to grow up with a show-business parent — with all the attendant challenges that come with it — she or he could do a lot worse than having as a father a nice, decent, down-to-earth Indiana boy like Hoagy Carmichael. The music star, the movie star, one of the biggest names in show business in the middle of the last century, Hoagy wrote “Stardust,” “Georgia on My Mind,” and “Ole Buttermilk Sky,” among several others that are still standards in the Great American Songbook.

IU Theatre’s production of “Stardust Road: A Hoagy Carmichael Musical Journey” runs through the weekend. | Photo by Greer Ramsey-White

Hoagy Bix is in town this month to help celebrate Stardust Road: A Hoagy Carmichael Musical Journey, a production of Indiana University Department of Theatre, Drama, and Contemporary Dance. The show opened yesterday (Wednesday, August 15) and runs through the weekend.

Stardust Road traces four decades of American history through music and dance, with all 23 of its songs written by Hoagy Carmichael.

Hoagy Bix zealously guards Hoagy’s legacy. “I’m enormously proud of my father. I love the work itself. I love what he thought up all by himself. So when I do these tours or this musical, I do them because I respect the work.”

It’s just that he didn’t have to do the same work his father did. “I grew up with a lot of kids whose mothers or fathers were big stars,” Hoagy Bix says. “The [Bing] Crosby kids grew up from here to where my car’s parked. And those kids tried to be their father. That’s a mistake. Somehow, that idea passed into my head and stayed there very early on — don’t try to be that guy in the den.”

The den was in the old William Wrigley Jr. mansion on Pasadena’s Millionaire’s Row. Wrigley and his family vacated the place almost immediately after Pearl Harbor — the chewing gum magnate felt certain the Japanese would attack Los Angeles next. Hoagy, by then one of America’s most well-known songwriters and lately getting into acting and writing songs for movies, moved his brood in. Hoagy worked (and played) in the den.

“People would come to the house for dinner. Inevitably, everything would move to the den where the piano was,” Hoagy Bix says. “Dad would play a whole bunch of things and I would ask him to play ‘The Monkey Song.’” Just as inevitably, Hoagy’s guests would beg him to play “Stardust.”

Bix Beiderbecke, a cornet player and co-namesake for Hoagy Bix, photographed in 1924. | Photo courtesy of Public Domain

In telling this tale, Hoagy Bix breaks out into “The Monkey Song”:

He beat licks with his sticks to a record by Bix

Till his rhythm was the talk of all the Congo

He had a gnu playin’ the kazoo

And a jug man rounded out the combo.

Catch the mention of Bix? Hoagy had met an up-and-coming cornetist named Bix Beiderbecke around 1922 while Hoagy was still an undergrad at Indiana University. Hoagy would stick around after graduation to study law, his father, Howard, pushing him to become a lawyer. But Hoagy had other ideas. Throughout college he played piano and wrote songs, often holding court in the fabled Book Nook on Indiana Avenue where the Gables building that housed the oddly named soda shop still stands.

Hoagy graduated law school, passed the bar, and even tried to work as an attorney for a year or two. That didn’t pan out.

No longer a practicing lawyer, Hoagy decided to devote his life to his true love, music, and, well, history followed. He’d already begun working in the music industry even as an undergrad. “One of the ways that Dad made money was he would book bands for sorority dances or some other events,” Hoagy Bix says. Hoagy brought a jazz group called the Wolverines down from Chicago to play here. Bix Beiderbecke played the horn for the Wolverines. Hoagy’d been blown away by Bix’s signature melodious horn work. “Dad was sort of in awe of Bix, and one day Bix said, ‘Well, play me something.’” Hoagy played a tune he called “Free Wheelin’.”

“Bix looked at Dad, and said, ‘You may want to be a lawyer, but there’s some magic on the ends of those fingers.’”

Later, Bix would go on to record the tune, renamed by him and his bandmates “Riverboat Shuffle,” the first penned by Hoagy to be recorded.

“That’s the reason I was called Bix,” Hoagy Bix says.

“Bourbon was their soda of choice and music was what reeled them in, together,” he continues. “They couldn’t get enough of it.”

Except Bix also couldn’t get enough of his bourbon. Alcoholism probably contributed to his death from pneumonia and fever in 1931 at the age of 28.

In 1938, Hoagy’s first child was born. He named the boy after himself and his great and good friend Bix.

“My dad was told he should be a lawyer, and by the time he was 26 he was a consummate musician,” Hoagy Bix says. “He never, ever had any training on any level. Not one hour. Not acting or singing. He was a composer. He had his own radio shows. He had his own television specials. He was in a lot of movies. And never, ever had a nickel’s worth of training. He just had it.”

Hoagy Bix (front right) with his younger brother, Randy, and their father, Hoagy, and grandparents Lida and Howard in the early 1940s at Lida and Howard’s home in Bloomington. | HC Series 3, Box 3, item 29. Hoagy Carmichael Collection, Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University

And yet, as a teenager, Hoagy Bix dabbled in show business. “I worked as an assistant director for Burt Lancaster at Columbia Pictures, and that was a marvelous experience.” He did that for four years.

By 22, Hoagy Bix had even more of an urge to strike out on his own. He moved to New York City to become a stockbroker. “I did six years of it. It was hard for me,” says Hoagy Bix. “You picked up the telephone, ‘Hello? Yes. 200 Shares? Yes. Thank you, bye.’ You bought some stock, you made a little money, and you went home. That wasn’t enough for me.”

So he moved to Boston where he became a producer for public television station WGBH. That gig lasted about four years. Then the Time-Life people hired him to produce a documentary film about Life magazine’s renowned photographers. After he finished the project, he moved to Pittsburgh where he worked with another of the last century’s icons, Fred Rogers, producing Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

Still, Hoagy Bix remained unfulfilled. A few years before, he’d traveled to Montreal for the world’s fair, Expo 67, with a woman whom, he says now, “I loved dearly, so dearly.”

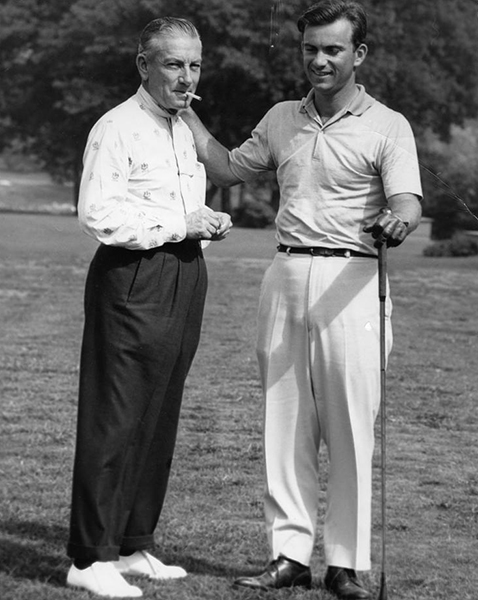

“After the fair,” he says, “we came back down through Vermont and she put a fly rod in my hand, which I’d never touched before. I was a golfer. I was actually a very, very, very good golfer. I tried to catch a fish for three days, but I realized there was an enormous amount to the sport. I knew nothing and I wanted to learn. I was a one-handicap golfer and I stopped completely and took up fly-fishing. Didn’t hit a ball for 47 years.”

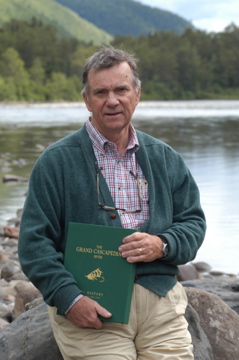

Hoagy Bix, holding “The Grand Cascapedia River,” one of several books he has authored on fly fishing. | Courtesy photo

By the mid-70s, Hoagy Bix had become so enamored with fly-fishing and so ready to launch another phase of his life that he chucked it all and decided to master making a special kind of fishing rod.

“I’d met this man, Everett Garrison, in 1968,” Hoagy Bix says. “He is considered to be one of the great rod-makers of all time.” Hoagy Bix began commuting to New York from Pittsburgh every weekend to study under Garrison. He committed to making a documentary film about the rod-maker and to write a book laying out Garrison’s techniques and secrets. “I thought, ‘This is now becoming a big part of my life!’”

Garrison died and Hoagy Bix inherited his tools. It seemed only natural for him to simply move to New York and devote himself to picking up where Garrison left off, making fly-fishing rods by hand.

Hoagy Bix made more than a hundred rods, all of them using a special, rare bamboo. “There’s only one place in the world that grows this particular species of bamboo called Arundinaria amabilis,” he says. “It’s a small area, 35 or so square miles in China. It’s fabulous. So strong and resilient. You cannot make a bamboo fly rod, successfully, out of any other natural material. If you’re lucky, out of 50 raw 12-foot poles, you’ll get 14 or 15 of them that are really good to use.”

Hoagy Bix has a couple of great lines about fishing. One of them goes like this: “Fishing is a jerk on one end of a line waiting for a jerk on the other end of the line.” Then there’s this one, from a 1982 New Yorker profile of Jim Deren, proprietor of New York City’s Angler’s Roost, a fishing gear shop: “Let me find a good fish and if I do, I’ll get a thousand dreams out of him before I catch him.”

“If I catch him,” Hoagy Bix says, “I’ll let him go. It’s not about whacking him over the head. It’s not about killing him. It’s about the experience of seeing the fish and trying to figure out how to put the hook in his mouth. Once the hook’s in his mouth, it’s over for me.

“I haven’t killed a fish since the ’90s and I’ve caught hundreds and hundreds of them. [International Game Fishing Hall of Famer] Lee Wulff said this: ‘A sport fish is too valuable to only catch once.’ Why kill him? I couldn’t do that.”

Hoagy, left, and Hoagy Bix on the golf course. | HC Series 3, Box 9, item 59. Hoagy Carmichael Collection, Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University

In the meantime, Hoagy Bix has helped establish the American Tap Dance Foundation along with the likes of dancers Gregory Hines and Tony Waag. He got involved in honoring the memory of Fred Astaire, with whom he’d become good friends while a young man in the Los Angeles area. And then there’s AmSong.

That’s the advocacy group he and a number of songwriters and their heirs founded to help protect creative property rights. “A lot of intellectual property was set to expire 75 years after it was copyrighted,” Hoagy Bix says. “Songs like ‘Stardust’ by now would be in the public domain. People could use the music and call it ‘Sawdust.’

“A bunch of us got together in Elmer Bernstein’s apartment in the Dakota building in New York. The [Irving] Berlins were there and the [Oscar] Hammersteins were there and [Stephen] Sondheim was there and I could keep going on and on. There were about 25 of us in the room. Mary Rogers stood up — Richard Rogers’s daughter — and said, ‘If we band together and work together we can bring this to the attention of Congress.’”

At the very least, the group wanted to extend copyright protections for another 20 years. “It was marvelous work for me,” Hoagy Bix says. “We’re still friends, a lot of us. Sure, it helped ensure more income for all of us, but we met a couple of people, guys in their 90s, who had already lost their own copyrights. One guy down in Nashville, a black guy, was living on Social Security because his copyrights to his songs were gone.”

Hoagy Bix and friends knocked on doors in Washington, D.C. “We worked for two and a half, three years. I learned a lot about how things work in Congress. We were in [Senator Ted] Kennedy’s office. He said, ‘I get it. This is fine. You’ve got my vote.’ So we go into the next office, Pat Leahy, senator from Vermont. We’ve got Margaret Whiting [a popular singer in the 1940s and ’50s] in the room. Margaret had a few drinks in her but she’s fine. Leahy says, ‘I’m only gonna sign on to this if Margaret sings “Moonlight in Vermont.”’ She got through it somehow. Leahy said, ‘Done. You’re all set!’

“That’s the way things are legislated — if it’s not war with China or something big.”

Hoagy Bix has a treasury of show-business anecdotes filed in his memory. There was the time Hoagy appeared with Frank Sinatra on a television variety show in the 1950s. Sinatra, by the way, like Hoagy, was never formally trained in music or acting. Otherwise, the two men were as different as night and day. “Yet they liked each other’s work,” Hoagy Bix says. “Dad was a big fan of Sinatra and Sinatra sang a bunch of Dad’s songs.”

Still a teenager, Hoagy Bix hung around the studio while his father and Sinatra worked. “Sinatra and Dad shared a dressing room. I knocked on the door and opened it. Dad wasn’t in there but Sinatra was. He turned around and looked at me, and says in a loud voice, ‘Get outta here, kid!’ And I ran!”

It wasn’t the first time Hoagy Bix ran for his life in a studio. Hoagy played a character named “Happy” in the movie The Las Vegas Story made in 1952 with Victor Mature and Jane Russell. Hoagy Bix was about 13 at the time. “Victor Mature had just come off a picture that did very, very well, called Samson and Delilah.” In the movie’s most memorable scene, Mature, as Samson, stands between two columns of the temple and pushes them apart, causing the entire structure to collapse.

“He was a big, strong, muscled guy. My brother Randy and I were there between two sound stages and Victor Mature came around the corner.”

Hoagy Bix and his brother gasped in awe.

“It wasn’t Victor Mature to us. We said, ‘There’s Samson!’ He said, ‘Who are you?’ We told him. And he reached his arms out and touched two opposing walls, Studio A and Studio B, and started to push. And we ran like thieves! We were sure those walls were coming down!”

Hoagy Bix is sharing the work of his father with a younger generation through “Stardust Road,” which features 23 of Hoagy’s songs. | Photo by Greer Ramsey-White

Hoagy also appeared in a Kirk Douglas vehicle, Young Man with a Horn, loosely based on the life of Bix Beiderbecke. Douglas’s co-star was Doris Day. “One of her first films,” Hoagy Bix says. “Dad had the first scene with her. He had to hold her hand underneath the table, she was so nervous.”

Hoagy’s was a name seemingly everybody knew — once. Now Hoagy Bix is working with a new generation, one that has to be brought slowly along to understand his father’s magic. “I have watched these kids embrace this music. The first two days of rehearsals, I thought, ‘Oh, Jesus, that guy — and maybe even that girl — is just not going to make it.’ We all were fearful, our director, Susan Schulman, our choreographer, Michael Lichtefeld, and our musical director, Larry Yurman. We were just so wrong. The kids have taken this music and this idea, gone home, and rehearsed all of this in their bedrooms until whenever, and come back prepared. That is a terrific thing. I would give my right leg, instantly, in front of you, if Dad could come to one of these performances.”

[Editor’s note: Michael G. Glab’s full interview with Hoagy Bix Carmichael can be heard today on his radio show, Big Talk, which runs on WFHB (91.3 FM, 98.1 Bloomington, 100.7 Nashville, 106.3 Ellettsville) every Thursday at 5:30 p.m. and will be available, along with podcasts of past shows, at WFHB.org. Each of Glab’s monthly profiles for Limestone Post is based on one of his Big Talk interviews and will be posted on the same day that the interview airs on Big Talk.]