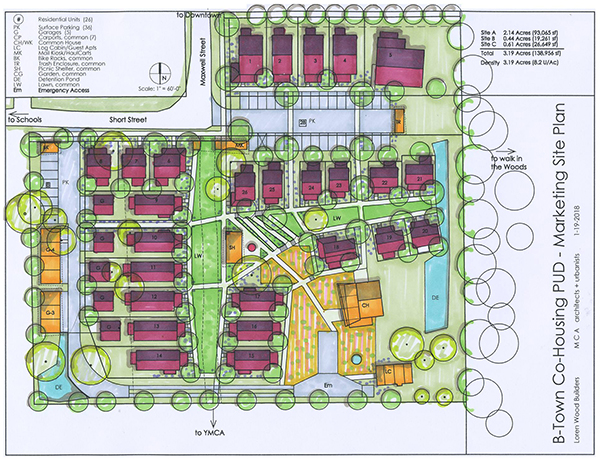

The Bloomington Cohousing Project is planning a collaborative housing community on the south side of Bloomington, where homeowners will live in individual houses but share other common amenities. Writer Michael Glab talks to co-founder Marion Sinclair and builder Loren Wood in his latest Big Mike’s B-town. The project has grown significantly since this early rendering was created, with even more amenities designed to foster community, with shared green space, gardens, buildings, and other features. | Courtesy image

She’s a retired nurse. He’s a former high school math teacher. Together, they’re hoping to form the first cohousing community in Indiana.

If all goes well, Loren Wood and his crew will turn over the first spadeful of dirt within days. And Marion Sinclair will be there, watching as her dream community begins to become a reality.

A more recent rendering of the Bloomington Cohousing site. | Courtesy image

Marion is the idea person, one of the co-founders of the Bloomington Cohousing Project. Loren, owner of Loren Wood Builders, is the person who’ll make Marion’s idea real. He came to this party a few years after Marion and her cohorts had begun noodling, cajoling, and crossing their fingers that one day they’d create a neighborhood just like the old ones of our collective, fuzzy memory. One where informal aunts and uncles, grandmas and grandpas, watch over all the neighborhood kids. Where different families get together for meals. Where the neighbor down the block might bring over some homegrown squash. Where people know each other by name. In short, a neighborhood pretty much unlike those most of us have ever known in 2018 Bloomington or any other small or big city in these United States.

The ideas behind cohousing — or collaborative housing — have been around at least since the time of Plato, who wrote about his vision of an ideal cooperative community. Thomas More’s Utopia, written in 1516, describes a community where neighbors dined, played, studied, and worked together. A Swedish author named Carl Jonas Love Almqvist in 1835 wrote of a “Universal Hotel” where residents shared labors and upkeep and, again, meals.

In the mid-20th century, several Swedish collectives started cohousing communities. Finally, in the early 1960s, the modern version of cohousing communities began springing up in Denmark. They spread throughout Scandinavia and then into the rest of mainland Europe. By the 1980s, cohousing developments were being formed in Canada and the United States. Today, there are many such communities in this country.

Marion Sinclair has been spearheading the Bloomington Cohousing Project for years. Design is moving along, with periodical updates from Loren Wood Builders. Group meetings such as this one will continue once the project is completed. | Courtesy photo

“There are about 160 built cohousing communities in the United States and many more in the planning processes,” Marion Sinclair says. “They are mostly on the east and west coasts, and Colorado’s a big state for cohousing as well. The Midwest hasn’t gotten so many.”

The planned development on 3.5 acres off South Maxwell Street will be Bloomington’s — and Indiana’s — first.

“I got interested in cohousing in the ’90s,” Sinclair says. “I was really taken with the idea. It’s a wonderful combination of having your own private life but having community there, also, when you want it. Ecologically, it just makes more sense to have a lot of shared amenities.

“I started groups here in Bloomington and each time we got a little farther. The last group, we started planning the community more and more.

“A friend, Janet Greenblatt, and I went ahead and bought a site that came up for sale,” Sinclair says. “It just seemed like it would be a perfect location. We moved ahead somewhat on it, but it was very difficult to form a stable group that was willing to put in the time and money to actually make this happen. It was sort of based on a dream at first. People are cautious about that.

“People also kept asking ‘What’s it gonna look like?’ ‘How much is it gonna cost?’ We didn’t have those answers.”

Sinclair and her friend Janet Greenblatt purchased the initial 2.5 acres near the YMCA and Bloomington Community Orchard on the south side of town. | Courtesy photo

Sinclair and Greenblatt had purchased the first 2.5 acres of undeveloped land bounded by the YMCA, a Montessori school, and some woods. The parcel of land is a stone’s throw from the Bloomington Community Orchard. Sinclair and the several dozen people who’d expressed varying levels of interest in joining the community started making collective decisions. Cohousing communities are democratic in that sense.

What Sinclair’s groups lacked was real money to get the project off the ground.

“Janet and I decided it was getting difficult and we weren’t moving ahead like we wanted to,” Sinclair says. “We decided we’d better get a developer to invest with us.”

One Sunday morning, somebody put the bug in Loren Wood’s ear. “I attend the Unitarian church periodically,” he says. “A year and a half ago, after service, a woman I’d known for years in the community approached me, and said, ‘Hey, I’m a part of this little housing community that we’ve been trying to get off the ground. It’s just sort of stalled out. I think you might be able to help us move the ball forward somehow.’

“She was a friend of mine, so I agreed to meet with them. I wasn’t particularly excited about it. I’m not a developer. I don’t consider myself a developer.”

So Wood met with the core group, the latest iteration of the several groups Sinclair had organized. The group already had been in discussions with the city and had submitted preliminary plans for approval. “They had an original design and some maps and renderings of houses,” Wood says.

“I’d never heard about cohousing. I didn’t know what it was. It sounded like, maybe, a commune,” he says.

Sinclair can clear up that misconception. “On a commune, you usually have income sharing,” she explains. “In cohousing, you generally lead your own life. You own your own house. So in that way it’s more traditional but you share a lot, too. You have a lot of common space so that you don’t need so much individually.”

Several dozen people are interested in living at the Cohousing Project property. These future community members get together for events at their future home, such as this community picnic. | Courtesy photo

Cohousing homes usually are a bit smaller than the average American home. The houses in Bloomington’s planned community will be arranged around a common green space with parking on the periphery. Residents will have to walk from their cars to their homes, with many passing their neighbors’ homes and, it is hoped, tightening their social bonds. There also will be a large common house with a big kitchen and dining room where the neighbors will gather for community meals (residents as a group will decide how often to have community dinners — the norm is at least one a week; all the homes feature full-sized kitchens). The common structure will also house, if the group so decides, a library, a child care center, a crafts room, a performance space, and other types of amenities that engender togetherness.

Residents will be collectively responsible for upkeep of the common house and the green space. They’ll tend a community garden. The group will own the rakes, the hoses, the shovels, and the lawn mower.

This was all new to Wood.

“I was skeptical,” he says. “But I was really excited by the land that they had. It just seemed very special. That intrigued me. And then the concept of smaller homes and a connected neighborhood. It was unique and different and spoke to the values that our company has placed over the years on this concept of building community.”

Loren Wood of Loren Wood Builders purchased the Bloomington Cohousing Property while he develops what he plans to be more than 30 houses in the space. | Courtesy photo

“We were a little burned out, working on the project for a few years,” Sinclair says. So she and Greenblatt sold their chunk of land to Wood. In the meantime, the parcel had grown by about an acre — Sinclair and Greenblatt snapped up a contiguous piece of land immediately after it became available — so Wood had to submit an updated Planned Unit Development (PUD) document to the city planning department. The city council approved that PUD in June and right now is passing judgments on the final permit applications.

Greenblatt, by the way, has dropped out as an active member of Sinclair’s planning group, although she still remains somewhat interested in buying into the community when it’s built — according to Sinclair, Greenblatt loves her current home.

“One of the underpinnings of a cohousing community is you’re designing the structure of the neighborhood to facilitate community,” Wood says. “Parking on the periphery so, as you walk to your home, you have to walk by your neighbors’ homes — not driving into your garage, shutting your garage door, and shutting yourself up in your private castle.”

The residents of the community will form a homeowners association, which some might recognize as a potential recipe for friction.

“Of course, there’s always going to be differences between people, but we, our group, has developed a mission statement which states our goals and our values,” Sinclair says. Prospective buyers will have to sign the statement, promising to honor the group’s rules and goals. “That’s how you know the people you’re going to live with have the same basic values. The group develops its own rules of how the community runs. In a regular neighborhood, you don’t know at all who’s going to be living around you.”

There are a few existing structures on the property, including this cabin, which will be fixed up and become one of the community’s homes. | Courtesy photo

Both Sinclair and Wood came to this moment from unexpected backgrounds. Sinclair, who grew up in Indianapolis, moved to Bloomington with her then-husband in 1977. Her husband spent his days running the couple’s landscaping business. Sinclair searched for ways to feel more at home in her new town.

“I wanted to get a part-time job so we could spend some time apart and I could get to know some people in the community,” Sinclair says. “I always thought it would be fun to work in a hospital, so I got a part-time job as a nursing assistant, and I said, ‘I like this — I might as well be a nurse.’ So that led to my nursing career. I worked at Bloomington Hospital for 34 years, 31 years as a nurse.”

Loren Wood, then a teacher, hit this town in the mid-1990s. “I taught at Aurora Alternative High School,” he says. (The school has since closed.) “We worked with kids who had not been successful in traditional school settings. That was why I’d gone into education. I wanted to work with kids who’d struggled.”

During summer vacations, Wood worked for builders and — devouring every book on the subject he could — taught himself the basics of construction. “I had this idea I would build my own house someday.” Eventually, he took a leave of absence from the Monroe County Community School Corporation, borrowed some money, and built a spec house for a private customer. “Within a month, I knew I wasn’t going back anytime soon to teaching.”

He opened Loren Wood Builders in 2010.

Both Sinclair and Wood have done their homework on cohousing, reading all available books and articles on the topic and independently visiting numerous cohousing communities in the U.S. Between them, the two have visited existing cohousing communities in Asheville and Durham, North Carolina; Boulder, Colorado; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Nashville, Tennessee. Both have visited with groups still planning their communities.

Wood, standing in center, speaks with residents on a common green path during a tour of Greyrock Commons in Fort Collins, Colorado. The Greyrock Commons design is similar to the planned design of the Bloomington Cohousing project. | Courtesy photo

When Sinclair and Greenblatt were considering selling their land to Wood, they wanted to be sure he’d move the project ahead in the way they’d envisioned. Many cohousing groups own the land from the get-go, as Sinclair and Greenblatt had owned their piece of property. Wood had his own idea. “Loren thought he would prefer to buy the land outright,” Sinclair says. “I think he didn’t want to get involved in group decisions on every little thing, which can slow the process down. But we were convinced that he wanted to do what we had planned.”

As a rule, the groups that start cohousing communities take on all the financial risk — if no one buys homes there, the group is stuck. In this case, Wood is taking on the risk. His reputation around town as a builder and a fair business person is sterling. [Editor’s note: Wood says the homes will range in size from 800 to 1,600 square feet and start around $250,000.]

Once the homes are built and the residents form the homeowners association, they alone will set rules for the community and make decisions. The latest iteration of Sinclair’s cohousing groups has a Meetup page with some 170 members. Of that total, Sinclair says, there are “a handful” of people she’s fairly certain will be buying homes in the new community. “We’re all wanting to see Loren’s community, how close it matches what we want,” she says. “We think it will.”

When asked if she’ll be an evangelist for the community once Wood builds the first few homes, Sinclair laughs. “I’ve been an evangelist for this for a long time! So I’ll probably keep right on going,” she says. Sinclair pledges to be an unofficial sales agent for the homes, visiting with prospective buyers or inviting them over to her new place.

One reason Sinclair is drawn to the cohousing idea is she’s facing the same near-future as millions of aging Americans. She loves her big home in Prospect Hill, but the place is getting a bit much for someone of her years to handle. For instance, she loves gardening. “But it’s a lot of work. I’m really going to enjoy having a bunch of neighbors to do the gardening with.

A rendering of one of the smaller homes coming to the property. Wood says the homes will range in size from 800 to 1,600 square feet and start around $250,000. | Courtesy image

“Everybody says, ‘Aw, I can’t believe you’re really going to sell your house.’ It was built around 1865 to ’70 and it’s a really neat old house, but it’s too big for me anymore. As I age, I need a smaller place.”

Grading and excavation will begin as soon as the city council approves Wood’s work permit applications. He expects to begin building the first homes by the end of winter and hopes to have move-ins before the end of 2019. Wood envisions more than 30 homes on the site. The Bloomington Cohousing Facebook page posts regular updates on the project’s progress.

“It’s a fun way to live,” Sinclair, the evangelist, says. “And the spontaneity — the sociability is very spontaneous. You don’t have to call and make play dates for your kids. And it’s very supportive of elders and children. You have mentors for the children. You have grandparents right there.”

One early Scandinavian cohousing advocate once wrote in a newspaper article: “Children should have 100 parents.”

“It works that way for the kids,” Sinclair says. “There’s a lot of babysitters around. And it’s a great place for elders who sometimes are isolated. The elders are great mentors for the children and the children are great companions for the elders. It’s a great place for families. There’s a lot of support.

“They talk about cohousing being the new old-fashioned neighborhood. I’m looking very forward to it and I think it’s going to be a joyful, fun place to live.”

[Editor’s note: Michael G. Glab’s full interview with Marion Sinclair can be heard today on his radio show, Big Talk, which runs on WFHB (91.3 FM, 98.1 Bloomington, 100.7 Nashville, 106.3 Ellettsville) every Thursday at 5:30 p.m. and will be available, along with podcasts of past shows, including last week’s interview with Loren Wood, at WFHB.org. Each of Glab’s monthly profiles for Limestone Post is based on one of his Big Talk interviews and will be posted on the same day that the interview airs on Big Talk.]