Editor’s note: Beth Edwards spent the last five years of her life dedicated to writing, photographing, and shooting documentary footage about Hoosier environmental issues for the Indiana Environmental Reporter.

Beth Edwards

Edwards and her colleague Enrique Saenz were hired by The Media School at Indiana University in 2018 to establish a statewide environmental news publication under the auspices of a university-wide initiative, Prepared for Environmental Change. They started from scratch and developed IER into a respected source for environmental news both around the state and nationally. By the time IER closed, due to a lack of funding, in 2023, its staff had won more than 30 state and national awards. Edwards placed first in contests with the Society of Professional Journalists, Indiana Pro Chapter; Woman’s Press Club of Indiana; and National Federation of Press Women. Her documentary about coal ash, “In the Water,” was screened at the Indy Film Fest, at the Lulea International Film Festival in Sweden, on WFYI public television, and by groups around the state.

Edwards made a significant contribution to the understanding of environmental issues in her home state. She died at age 45 of natural causes at her Bloomington home in June 2023, the same month IER closed.

Limestone Post has chosen these four stories that represent some of the best of Edwards’s work, and which are still relevant today:

Coal Ash: The Poison Seeping into Indiana Water (2023): As a shipment of toxic waste from an Ohio train wreck sparks concerns in Indiana, lawmakers support lenient rules on coal ash, which could threaten the waters of Lake Michigan. Jump to the Coal Ash article.

A Question of Scale (2020): Farmers and environmentalists debate the impact of confined animal feeding operations on the environment and on people’s health. Jump to the article A Question of Scale.

Contaminated Ground (2020): Amid alarming cancer cases, Martinsville residents rally to keep their water clean, decades after a dry-cleaning business polluted the city’s downtown. Jump to Contaminated Ground.

Jobs vs. Health? Controversial Coal-to-Diesel Plant Would Be First in U.S. (2019): A grassroots group in southern Indiana fights against the construction of a plant that could cause significant pollution in a small community. Jump to Jobs vs. Health.

Photos by Beth Edwards unless otherwise noted.

Coal Ash: The Poison Seeping into Indiana Water

published March 6, 2023

News that toxic waste from the Norfolk Southern train derailment in February 2023 in East Palestine, Ohio, would be shipped to a landfill in Roachdale, Indiana, has rung alarm bells with everyone from local residents to Gov. Eric Holcomb, who has ordered testing of the waste for possibly dangerous levels of dioxins.

Yet an equally poisonous substance, present in far greater quantities in communities around Indiana, has received much less attention, with the Indiana Legislature refusing this session to even hear bills that would regulate its safe disposal: coal ash.

The toxic material left over after burning coal for electricity has been found in groundwater at every Indiana facility where coal was burned for electricity, largely as a result of poorly regulated storage that has led to toxins seeping through the soil. It contains harmful chemicals such as boron, lead, mercury and arsenic, and poses the possible risk of blood vessel damage, anemia, neurological and cardiovascular problems, as well as cancer in the skin, bladder, liver and lungs.

NIPSCO’s Michigan City Generating Plant

Among multiple areas of concern to environmental justice groups and residents, one has risen to the top of the list in terms of urgency: the possible leaking of coal ash from the Northwest Indiana Public Service Co. generating plant in Michigan City into Lake Michigan, which supplies water to 10 million people in Indiana and neighboring states. Seawalls with a limited lifespan are the only barrier between toxic coal ash ponds and the lake, where increasingly high water levels are being fueled by climate change.

“If we have an environmental disaster on the shores of Lake Michigan, it will be irreparable,” Susan Thomas, director of legislation and policy for environmental justice group Just Transition Northwest Indiana, said in a news conference in December. “We will never be able to claim back our Great Lakes ecosystem, our beautiful source of wonder and recreation and our drinking water.”

EVALUATING A CLOSURE PLAN

NIPSCO’s Michigan City generating station lies on 123 acres of land that stretches along the south shore of Lake Michigan and the western edge of Michigan City.

The plant began operating in 1931. From 1931 to 1950, NIPSCO built steel pile barriers along the border of the property next to Lake Michigan and Trail Creek. Using a mixture of coal ash, sand and soil, it created “made land” behind the walls, which are up to 40 feet deep.

Steel pile barriers bordering the Michigan City Generating Plant | Photo by Timeless Aerial Photography, courtesy of Just Transition Northwest Indiana

NIPSCO used the made land to expand out toward the lake, building parking lots, additional structures and coal ash ponds.

In 2018, the company announced its plan to close the station and move toward more renewable forms of energy. It began removing coal ash from the station in April 2022, trucking the ash from the ponds to a lined landfill at Schahfer Generating Station in Wheatfield.

The current closure plan includes removing the ash from the five ponds located on the made land but doesn’t include removing the made land itself, even though it, too, is contaminated. That means some ash would stay in place, directly beside Lake Michigan, the drinking water source for around 10 million people.

Since the plant closure was announced, residents have become increasingly concerned about the methods proposed to remove the on-site coal ash, as well as the safety of the site itself.

“NIPSCO was ready to pull the wool over our eyes and leave us with an inheritance that lasts thousands of years. Millions of tons of toxic coal ash waste is fouling our air and water as we speak,” said Ashley Williams, executive director of Just Transition.

Just Transition Northwest Indiana Executive Director Ashley Williams speaking at a rally in front of the EPA in Chicago. | Photo by Matthew Kaplan

In a statement to the Indiana Environmental Reporter, NIPSCO communications manager Tara McElmurry said the Indiana Department of Environmental Management and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have approved the cleanup plan as a first step and will determine what additional steps may be necessary to ensure the long-term safety of the community and the environment.

She said the intent of the current work is to address the primary source of the known groundwater impacts in accordance with the environmental regulation in place.

“The primary source is believed to be the ash ponds — 100 percent of which is being closed by removal,” McElmurry said.

McElmurry said NIPSCO believes having access to clean water and clean air is an essential right.

“Protecting the environment is also a vital component to achieving the long-term economic viability of any community,” she said. “Significant progress has been made in recent decades to improve environmental quality in our region and our state. And, while efforts are ongoing, there is much success to point to. Our current work to remove coal ash material and close our coal ash impoundments at our remaining coal-fired electric generating facilities — which are planned for retirement by 2026–2028 — represents another positive step forward.”

FAILING SEAWALLS?

Despite the company’s claims about protecting the environment, residents remain skeptical about how much the company was willing to do to protect residents from pollution.

In June 2022, Just Transition and its partner agencies held a town hall meeting in Michigan City to discuss the results of a report by national environmental law firm Earthjustice on the stability and integrity of the steel sheet seawall that separates the coal ash from Lake Michigan.

The report was commissioned out of frustration. Thomas, who is also the press secretary for Just Transition, explained at the meeting at the Michigan City H.O.P.E. Community Center why the group reached out to Earthjustice.

Just Transition NWI director of legislation and policy Susan Thomas speaking at a rally in front of the EPA in Chicago | Photo by Matthew Kaplan

“As you know, the lake is at record high levels. In the town I live in next to here, we lost a parking lot. In Chicago an entire trail along the lake, swept away,” Thomas said. “When we saw this happening, we thought, ‘Oh my God, what is happening to the pit over by the lake?’ We had people coming to us and saying, ‘We see waves going over there [over the seawall into the coal ash pond].’”

Just Transition reported these observations to both IDEM and the EPA, providing drone footage (starting at 1:11) showing the waves cresting over the top of the seawall.

The footage led to a more recent inspection of the seawall by IDEM, but Just Transition still had concerns.

“No one has been connecting the dots at these agencies,” Thomas said.

Earthjustice engaged a Canadian firm, Burgess Environmental, to review the assessments that NIPSCO, IDEM and other agencies commissioned to assess the stability and integrity of the steel sheet pile barriers that separate the ash from Lake Michigan.

The report found three main areas of concern: The steel sheets do not stop the seepage of contaminated water into Lake Michigan; corrosion has and continues to undermine the integrity of the walls; and movement of the walls has been and continues to be significant.

“Corrosion of up to 25 percent of steel sheet thickness has been measured. Ultimately, the steel sheet pile all will corrode and fail if it is left in place,” said Gordon Johnson of Burgess Environmental.

Johnson also pointed out that coal ash causes an accelerated corrosion rate.

“The resulting loss of thickness at the joints of the sheet pile wall increases the overall permeability of the structure, and corrosion at the face of the steel sheet reduces the strength and bending resistance of the barrier,” he said.

Thomas said Just Transition members have had to become citizen scientists because IDEM and the EPA are moving so slowly.

“This is a ticking time bomb. We don’t have time to move slowly,” she said. “We need this cleaned up right now.

“It’s not a question of if the wall will blow, it’s when.”

McElmurry at NIPSCO, however, said the seawalls remain stable and don’t pose an imminent threat. She said an in-depth assessment of the walls rated the structure as “fair,” which means all primary structures are “sound” with some level of expected deterioration but nothing to significantly reduce their ability to provide shoreline protection.

“The seawall structures were intended to provide armoring for the shoreline along the lake and the creek, and they support the overall operations of the generating station,” McElmurry said. “The walls were never designed to provide an impermeable seal from water, and the known groundwater impacts are being addressed by the cleanup work.”

Residents are unhappy with the extent of NIPSCO’s cleanup efforts, but the company is still making them and other customers pay for it, asking the Indiana Regulatory Commission to approve a $20-per-month rate increase across the board.

Just Transition organized an in-person meeting with the Indiana Office of Utility Consumer Counselor in Michigan City to give residents a chance to comment on the rate increase. The OUCC is the state agency charged to represent ratepayer interests.

After the meeting in Michigan City, the agency recommended that the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission deny the NIPSCO rate increase.

“This is an unjust and unethical hike that shifts the burden away from billionaire industrial consumers [NIPSCO has the highest rate of industrial consumers in the U.S. at 60 percent] and onto the backs of the residential and smaller consumers already struggling with high costs of energy, fossil fuels and inflation,” Thomas said of the proposal. “The last rate hike shifted the burden off of industry by 19 percent onto consumers in 2018/19. NIPSCO is trying to turn a profit off of this by qualifying this as capital cost when it’s actually an operations and maintenance expense that should be accounted for. Further compounding the problem is that it doesn’t cover complete removal of all the toxic ash at the site: only 10 percent is being excavated while 90 percent is slated to remain indefinitely on the lake.”

Thomas said other solutions, such as securitization options, could provide for the complete removal of the toxic coal ash without further burdening ratepayers.

“Plus, if the aging steel wall holding it all back gives way, the cost will be far, far higher than taking care of this issue now,” she said.

NIPSCO said the rate increase is necessary to cover the $40 million project cost. Indiana and the federal government do allow energy providers to recover “reasonable costs” associated with federally mandated projects.

The utility is proposing to spread the costs through 2032 with a $0.30 increase per month in an effort to reduce the impact on customers.

The commission will announce its decision this summer.

CLOSING A LOOPHOLE

Having worked at both the local and state levels to bring awareness to how a coal ash spill could affect Lake Michigan, in December Just Transition tried to appeal at the federal level.

“The two communities where these toxic coal ash pits sit are environmental justice communities, largely Black, largely Brown and low income. We’re asking the EPA to help us change the law to protect these communities and to protect Lake Michigan,” Williams said.

In December, the organization and members of other environmental and activist groups delivered a petition with more than 2,000 signatures and a joint letter from 50 organizations in the Great Lakes Region to the EPA Regional Office in Chicago, urging it to make utilities complete a full clean closure of coal ash on their properties.

Just Transition Northwest Indiana members delivered a petition with more than 2,000 signatures and a joint letter from 50 organizations in the Great Lakes Region to the EPA Regional Office in Chicago in December 2022. | Photo by Matthew Kaplan

Williams said the current Coal Ash Rule doesn’t mandate the removal of legacy coal ash. She urged the EPA to close the loophole before a coal ash spill destroys the lake.

“Time is not on our side. With each passing day, we fear, ‘Will this be the day that the seawall finally blows in Michigan City?’ Will our community be the victims of yet another environmental catastrophe that could have been averted?” Williams said.

“Half of our population, the majority of them residents of color, struggle to meet their basic needs. We in Michigan City and our families can’t get them [back] nearly 100 years of living and breathing toxic coal pollution. But we refuse to be complicit in the destruction of our futures.”

Pastor Jacarra Williams of New Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Michigan City, spoke to the crowd that gathered when the petition was delivered.

“To not say anything means I agree with everything going on, and I do not agree with it,” he said. “So, I’m here to voice my opinion and say it’s time for NIPSCO to stand up and take accountability for their actions. It’s time to stand up and do the right thing. This doesn’t just affect us in Michigan City, but it affects all of our sisters and brothers because it’s not a white issue. It’s not a black issue. It’s not a Hispanic issue. It’s an issue of humankind.”

A delegation of five members delivered the petition to the EPA. Just Transition is waiting for a response.

In the meantime, Just Transition continues to hold legislative action meetings and to urge people on social media to call Senate Environmental Affairs Committee chair Sen. Rick Niemeyer to request bill hearings.

Just Transition and others lobbied for two bills this legislative session that could have helped make the NIPSCO plant in Michigan City more secure. Both bills died in committee.

Senate Bill 399, authored by Sen. Rodney Pol, D–Chesterton, would have established a state policy that favors recycling coal ash and banning it from being stored in a flood plain, touching ground water or being left in an unstable area.

House Bill 1190, authored by Rep. Pat Boy, D–Michigan City, would have required the removal of coal ash to a lined landfill or for recycling for beneficial use. Air monitoring would be required during the removal process.

“I’d like somebody to listen to my bill and actually make it a priority,” Boy said early in the session. “I’ve been through it twice. Last year the chair of the committee asked for a summer study and that was denied. They’re not looking at it as a problem. They’re kind of burying their heads in the sand.”

Instead, lawmakers are ensuring that coal ash regulations are as lenient as they can legally be.

House Bill 1623 would prohibit IDEM from making any rules for a proposed state coal ash permitting program that are more stringent than federal regulations. The bill passed the Indiana House of Representatives and will now be considered by the Indiana Senate.

If the bill passes, any regulations concerning coal ash would most likely have to come from the federal level.

Members of Just Transition said no matter what happens, they will continue to fight for environmental justice across the state.

“The time is now for our communities to not just survive, but to truly thrive,” Ashley Williams said. “To dream of all the things that our city can be, that it deserves to be, without a toxic waste dump in our backyard.”

A Question of Scale

Farmers, environmentalists debate impact of confined animal feeding operations

published August 11, 2020

Editor’s note: This article won first place for green/environmental writing in the 2021 Indiana Woman’s Press Club awards; first place for environmental reporting in the 2021 Society for Professional Journalists, Indiana Pro Chapter awards; and first place for specialty articles, green/environmental in the 2021 National Federation of Press Women Communications Contest.

Surrounded by rolling green hills, Richard and Janet Himsel’s farmhouse in Danville, Indiana, just west of Indianapolis, was idyllic for many years.

But a few years into their retirement, new neighbors moved in across the street in the form of 8,000 pigs.

The Himsels, longtime pig farmers themselves, have changed their way of life because of fumes from the large-scale confined animal feeding operation, or CAFO. They no longer open their windows. Janet has given up gardening. The grandchildren don’t visit as much anymore, and the value of the Himsels’ property has plummeted.

A suit filed by the Himsels and another couple against the corporations that run the hog farm, one of which is owned by another branch of the family, may go to the U.S. Supreme Court. Their story is a clash of the old ways versus the new — the small family farm versus large-scale corporate agriculture.

Supporters of large-scale farming say the efficiencies of the system result in lower food costs, while using less land, energy and water than conventional farming methods. They say there’s room at the table for a variety of pork-rearing practices.

But others, including environmentalists at the state level, say so-called factory farms are bad for the land and for the local food system that keeps traditional family farms alive.

“CAFOs didn’t make farms more profitable, it really just reduced the margins,” said food systems analyst Ken Meter, president of Crossroads Resource Center and a consultant for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency. “By having a lot of animals that could be raised at a lower price, it put pressure on every farmer to lower their prices, which lowered markets for all farmers in the state.”

Illustration by Sophia Chryssovergis

A MODEL OF EFFICIENCY

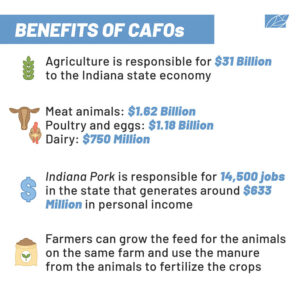

Agriculture is a big business in Indiana, contributing $31 billion to the state. Of that, $3.55 billion comes from animal and animal product production.

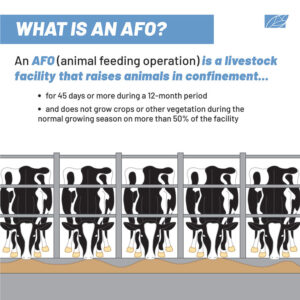

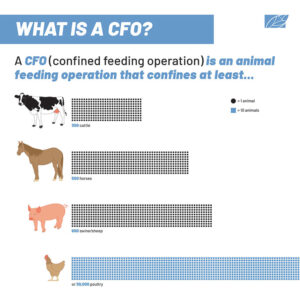

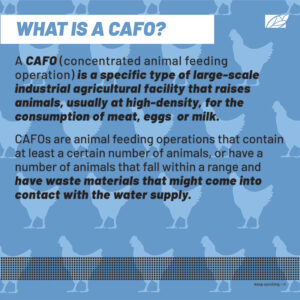

Today, more than 85 percent of the livestock in Indiana are raised in a CFO, or confined feeding operation. These large-scale industrial barns house thousands of animals, allowing farmers the ability to control the environment in what they believe is a more efficient way of raising livestock.

More than 1,800 farms in the state have a CFO on their property. Of those, 796 are the more intensive CAFOs, or confined animal feeding operations.

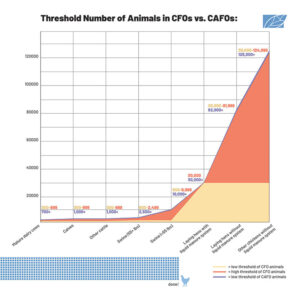

The difference between a CFO and a CAFO is size. All farms with at least 300 cattle, 600 swine or sheep, 30,000 poultry or 500 horses in confinement are CFOs. Those that allow for 1,000 cattle, 10,000 swine less than 55 pounds, 82,000 laying hens or 55,000 turkeys are CAFOs, which are subject to additional state regulations.

For the past several decades, farmers nationwide have been encouraged to specialize and also to industrialize, which has led to the rise in CAFOs.

“Confined livestock has a long history. Indiana started regulating it clear back into the early ’70s, even before there was a Clean Water Act,” said Josh Trenary, executive director for Indiana Pork. “The concept of bringing pigs indoors isn’t new, it’s just there used to be a lot more smaller barns dotting the landscape than there are now.”

Trenary said the fewer, larger barns allow farmers to produce more pork with fewer resources, leading to lower consumer costs and also a smaller environmental footprint.

“We’re raising hogs on roughly 76 percent less land, 25 percent less water, 7 percent less energy and 7.7 percent lower carbon emissions per pound of pork than ever before. That’s good for everybody,” he said. “Confined hogs are housed in temperature-controlled buildings and are very comfortable for the animals. Confined hogs do not need to dig a hole in a pasture and create a self-made swimming or cooling area.”

Indiana Sen. Jean Leising, chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee, says properly managed confined feeding operations enable farmers to meet the demand of meat in the U.S.

“Outdoor production of swine causes serious erosion and environmental issues and produces few animals,” she said.

Pig farms can be organized in a few different ways. Farmers can be independent operators, meaning they own the whole business, or they can partner with other farmers or corporations to raise the pigs.

In such corporate partnerships, the farmer owns the land and equipment and provides the labor and care for the pigs, but doesn’t own the animals. In return, the other party pays for antibiotics, veterinary care and feed. Sometimes, the farmer is given exact instructions on care and incentives for meeting or exceeding goals. However, each contract is unique.

Illustration by Sophia Chryssovergis

Trenary said attention to feed types, genetics and building design means the commercial industry can continually learn to do more with less on a larger scale.

“You’ve got to have safe, affordable food that’s plentiful, and you want to be able to produce that food as efficiently as possible to minimize the environmental impact for producing that protein,” Trenary said.

But he doesn’t think one kind of pig operation should supplant another. There’s a reason for the wide variety of systems for raising pork, he says, and he understands the market for niche or organic products.

“You still need the ability to raise and process those types of products,” he said. “It’s also going to typically be not as efficient and a little more expensive to the consumer. So, you got to have a suite of options to be able to accommodate every consumer.”

HOW A CAFO SAVED A FAMILY FARM

Nick Tharp never thought of farming as a professional option. He studied a related field at Purdue University, but he didn’t think he would be the one doing the actual farming.

Then he met his future wife, Beth, whose parents own Legan Livestock and Grain in Putnam County.

The Legans bought their farm in 1989 and raised sows on outdoor lots. In 1997, they decided to switch to a CAFO in order to be more competitive and to provide better care for their animals. They built a second CAFO just before Nick and Beth’s 2010 graduation from Purdue.

“They expanded our farm, which allowed us the opportunity to come back and farm with her parents here, and gave them the ability to continue to farm,” Tharp said.

The Tharps are now equal partners with the Legans in the farm.

Tharp says a CAFO has allowed the families to focus on the health and performance of the animals. Before his in-laws brought the sows inside, each sow was weaning eight to nine pigs per litter. Now they are up to 12 to 13 pigs per litter, increasing their profits and becoming more efficient.

Illustration by Sophia Chryssovergis

On the Legan farm, corn and soybean crops, raised via a no-till system to preserve soil structure, provide feed for the pigs. In turn, pig manure fertilizes those crops, creating an ecosystem the farmers can fine tune. For example, if Tharp notices the fertilizer is lower in one element, he tweaks the crop to produce higher-nutrient manure.

“Part of it is to then being able to capture those nutrients in the manure and getting that nutrient applied to where the growing crops need it,” Tharp said. “That’s allowed us to look at utilizing that as a resource that it is. We can really look at the production of that crop and be able to precisely utilize that nutrient to the best of our ability.”

Tharp not only helps run a large-scale pig production farm that sends pork all over the U.S. and the world; he also has a small local meat production business.

After neighbors asked where they could buy the pork he produced, Tharp decided to offer a frozen product platform. He works with health officials and a local state-inspected processor to make sure he’s following regulations.

“It’s really kind of blossomed from there,” he said. “We have people in neighboring counties that are coming. They want to be able to put a face with the farmer that is producing that protein, and so it allows us to fill that need, that desire of the consumer at that level.”

Tharp now also offers lamb and chicken and has partnered with a neighboring farmer who raises beef.

He understands people might have concerns about CAFOs, but says his farm operates under core values such as stewardship of the land and animals, and of the people who work at the farm. His family also believes in being an asset to the community, sponsoring math bowl and Little League teams, providing ham to neighbors for the holidays and having a community picnic on the farm in the summer.

“We’re trying new things, looking at different management practices with the pigs, just to continue to do better at what we do, each and every day,” Tharp said. “We want to be proactive and really be involved and be a good neighbor, and that’s something that’s important to us.”

SAFETY CONCERNS — FOR ANIMALS AND HUMANS

While large-scale operations may be efficient and productive, they also raise concerns about animal welfare, water quality issues, antibiotic resistance and smell.

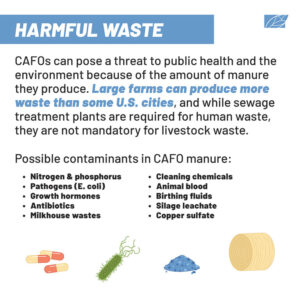

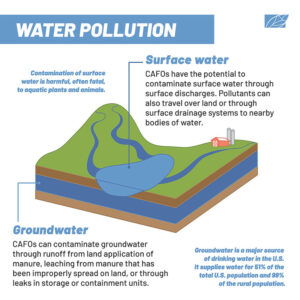

“A mature dairy cow is going to produce the equivalent of urine and feces as roughly 14 people,” said Kim Ferraro, senior staff attorney and agriculture policy director for the Hoosier Environmental Council. “They’re producing a lot more waste than humans do, and we’re not regulating that waste the way we do human waste.”

CAFOs’ facility design, manure handling and storage and monitoring are all regulated through the Indiana Department of Environmental Management. Anyone wanting to start or expand a CAFO must apply for a permit, have all plans reviewed and be approved by IDEM before beginning construction.

Illustration by Sophia Chryssovergis

The owner is required to notify all residents within a half-mile radius of the proposed location, adjoining property owners and the county commissioners for that location. Every permit is open to a 33-day public comment period, where citizens may voice concerns or ask questions about the proposed CAFO.

IDEM visits each CAFO once every five years for a compliance check. If a complaint is filed against a farm, IDEM will follow up and, if necessary, start an investigation.

Manure from a CAFO must be tested annually, and soil testing must be done every four years, in accordance with state laws.

One of the main concerns about CAFOs is manure and manure storage.

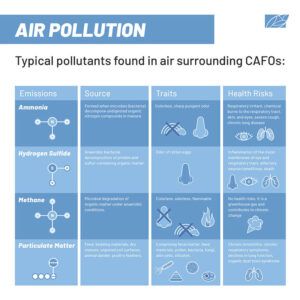

“Livestock waste gets to be stored in massive outside waste lagoons that are unlined,” Ferraro said. “That waste then can overflow into surface waters, leach into the ground, and, as it decomposes, that’s a lot of really noxious and dangerous air pollutants in the air like ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and others.”

Hydrogen Sulfide is a colorless, flammable gas that produces an odor like rotten eggs. It is produced by the bacterial breakdown of the animal waste. It can cause sore throat, headaches, nausea and insomnia.

Ammonia is also a colorless gas that produces a strong odor. It is naturally produced by microorganisms in the manure. Ammonia can also cause burning sensations and irritation to the nose, lungs, throat.

CAFOs are exempt from the federal Clean Air Act, and in June of 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency adopted a rule exempting farms from reporting under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act.

In the IDEM CFO guidance manual, there are five approved floor/liner options for a manure storage structure, from an earthen floor to a 5-inch concrete liner with reinforced steel.

Most farmers use manure from their CAFOs as fertilizer for crops, either on their own fields or on other farms, reducing the amount of chemical fertilizers.

The state has strict regulations regarding the application of manure, such as avoiding weather conditions that could lead to runoff, amounts that can be applied, and the operator who is applying it.

However, even with state restrictions, manure is getting into the water.

In 2018, IDEM released a state water and assessment report. Of the 62,547 miles of water designated for recreational use/full body contact in Indiana, only 32,848 miles were tested for possible contamination. Of those, 24,687 showed the presence of E. coli. That means 75 percent of the waterways tested and 40 percent of the total, even without full testing, contained E. coli.

Illustration by Sophia Chryssovergis

The same report lists sources of impairment. Animal feeding operations (nonpoint source) have impacted 10,600 miles; permitted runoff from CAFOs, 1,889 miles; and livestock (grazing or feeding operations), 6,345 miles. That adds up to 18,834 miles of Indiana’s waterways.

Trenary says the risk of the E. coli source being from livestock is mitigated by strict regulation of manure storage and application.

“Manure isn’t allowed to leave the barn site unless it is being land applied at agronomic rates, and IDEM requires the farm to have enough land to meet these requirements,” he said. “Both rate and predominant method of application [injection] help to lessen the risk of manure making it to surface water both from surface runoff and tile drainage. This has obvious environmental benefits but also means that the nutrients from the manure are properly placed to be utilized by the crop as fertilizer.”

FROM FRESH AIR TO FOUL

The Himsels are no strangers to manure.

In 1938, Richard Himsel’s father, Arthur, bought 26 acres of land in Danville and began to raise crops and livestock, including pigs in the open air. Richard joined him and took over the operation of the farm after Arthur’s death.

“The most important thing the young pigs and hogs need is to be on the ground, in the dirt,” Himsel recalls his father saying.

But with their pigs in the field, the Himsels never encountered the kind of stench that now wafts past the farmhouse where Richard was born.

In 2013, Himsel saw a notice in the paper regarding a hearing before the Hendricks County Plan Commission to have the land across the street rezoned and approved for CAFOs use.

The Himsels went to the meeting.

“The whole community was there. They were all objecting to it,” he said. “Not only me, even though I was the closest. There are a lot of people in the neighborhood that had health issues, and everyone had a real strong inkling that this thing would be a detriment to the value of their property.”

Despite community concerns, a spokesperson for the property owners, assured the residents they were using new technology and state-of-the-art environmental protections to keep odors and possible discharge at bay.

Illustration by Sophia Chryssovergis

“One of the representatives said this is a new kind of innovation and odor would never be that strong, and there’s a good chance you wouldn’t even smell it,” Himsel said. “Well, he was right. We did not smell anything for three whole days, and then after that it started.”

In September 2013, CAFO owners — one of whom is Richard Himsel’s first cousin — built two 33,500-square-foot buildings with ventilation fans, slatted floors and concrete pits to collect and store 4 million gallons of liquid waste from 8,000 confined hogs.

“I have a lot of throat problems, if I breathe a lot of it,” said Himsel. “I lose my voice. My wife had a lot of problems getting used to it, and for a while she stayed with our daughter in Indianapolis because she couldn’t live here.”

The large ventilation fans needed in a CAFO to help with environmental control for the pigs pull the odors out of the building. Himsel said they blow the stink and the fumes across the neighborhood.

“We’re 79 years old. We’d like to move to town, get a condo or something, because to keep up this piece of property, it takes a lot of work,” said Himsel, who retired in 2000 and rents his land to a tenant. “I had to accept another job to try and survive because the value of our property has been decreased so much. It took away our retirement. Some people say it’s 60 percent. I can tell you it’s closer to 100 percent value loss.”

In 2016, the Himsels and another couple, the Lannons, decided to sue the owners of the CAFO with the help of the Hoosier Environmental Council. The suit eventually made it to the Indiana Supreme Court in January of this year, but the court voted 3-to-2 in the CAFO’s favor.

“It was a really close call, so we were almost there, but we’re taking it to the U.S. Supreme court now,” Ferraro said. “So, it’s still an ongoing case.”

The right to farm

Citizens living near CAFOs have little to no legal protection. State and federal laws regulate nutrient pollution from CAFOs, but not air pollution or odor.

Indiana has two laws that protect factory farm owners. The Right to Farm Act prevents owners of factory farms from being sued by neighbors who feel their land or health might have been harmed by farm practice. The act is meant to encourage agriculture production and allow farmers to work without fear of being sued.

In 2014, Indiana lawmakers passed Senate Enrolled Act 186, which states, “The Indiana Code shall be construed to protect the rights of farmers to choose among all generally accepted farming and livestock production practices, including the use of ever changing technology.”

The Himsels are challenging these laws in their suit, saying they violate their equal protection and due process rights and amount to an unconstitutional taking of their property rights.

“The federal constitution and our state constitution prohibit the government from passing any law or taking any action that would take away someone’s private property without just compensation,” Ferraro said. “That’s called a taking, and it’s unconstitutional. We’re going to take that to the U.S. Supreme Court now.”

Himsel said neither government officials nor attorneys have visited their home.

“Nobody has come to our property and looked at our situation to see what we actually face, what we put up with,” he said. “So, we keep fighting it, and keep fighting and working for things.”

FOOD AS A COMMODITY

Ken Meter is a one of the most experienced food system analysts in the U.S., having conducted economic analyses of local food networks in 40 states, including Indiana.

“Once you transform food from a community function into a commodity, you separate the farmer from the consumer, and you start growing for what the market will bear, rather than what your neighbors need for food,” Meter said.

The majority of crops raised in Indiana, like corn and soybeans, are grown for livestock feed, not human consumption. The state has 15 million acres of farmland, and 90 percent of what is grown or produced is exported to other states or countries.

Which means 90 percent of the food eaten in Indiana is imported to the state at a loss of $14.5 billion to the state economy.

Illustration by Sophia Chryssovergis

Meter said for a long time people treasured the idea of larger, more industrial farms because they appeared to represent progress. In reality, he argues, CAFOs didn’t make farms more profitable.

“You can’t argue from the data that CAFOs are good financially for the state of Indiana,” he said. “They were good for some farmers who adopted at certain times, that had more favorable conditions. But they haven’t created a more lasting, more sustainable agriculture in the state.”

Meter estimates that if every consumer in Indiana bought $5 a week from local farmers, that would generate $1.75 billion for the state and farmers of Indiana.

Ferraro said economies of scale and unfair market competition mean global companies can create efficiencies that local farmers can’t compete with.

“So, they control the markets, they control the price that gets paid, they control all aspects of production, and so the little guy can’t compete, and it’s kind of the Walmart effect, just unfair competition. And that is all because of policies that we have in place that have allowed that to happen,” said Ferraro.

The Indiana State Department of Health and Board of Animal Health issued a joint statement to the Indiana Environmental Reporter about farm size.

“Indiana laws do not create an advantage or disadvantage for farms of any size,” the statement said. “Most farms in Indiana are independent. There are over 56,000 farming operations in Indiana and 96 percent of those farms are family owned and operated. In fact, the state offers a number of programs to assist smaller and startup farmers who grow, raise, package or produce products in Indiana.”

But Ferraro believes a CAFO shouldn’t be called a farm.

“In fact, I don’t even like the term factory farm. I don’t like calling them a farm in any way. They’re not,” she said. “They’re an industry. They should be regulated like an industry because they have an industrial scale with an industrial pollution impact. Yet, they’re regulated as if there’s somehow a bucolic little farm with cows running out in the pasture. They need to be regulated responsibly and required to control their emissions and impact just like every other industry is.”

She believes regulation would result in improved technologies and reduced pollution, as well as increased public awareness that would enable consumers to make educated choices about the food they buy.

“It’s been my experience that most people, when they find out that this is where our meat, poultry and dairy come from, they don’t want to buy that stuff,” she said.

But she acknowledges people with lower incomes often don’t have a choice.

“Buying responsibly typically means a higher cost, and so education alone isn’t going to do it,” she said. “It still has to come from a policy legislative perspective.”

Illustration by Sophia Chryssovergis

ROOM AT THE TABLE?

Pig farmers have been hit especially hard by COVID-19, but Tharp believes you have to have a little faith as the market fluctuates.

He would like to keep the business viable not only for now, but also in case one of his daughters might want to take over the farm one day.

“Having the opportunity to produce food for the world and really look at how we can utilize the resources we’ve been blessed with is pretty cool to me,” he said.

Trenary believes raising pork isn’t limited to just one option.

“There’s a variety of ways to raise pork, and there’s room for everybody,” he said. “I get frustrated with kneejerk value judgments I hear based on one production technology over another or one production philosophy over another. There’s room for everybody out there and markets for everything. There’s a reason things shake out proportionately like they do, and it creates a lot of opportunity in our rural communities.”

Ferraro agrees there need to be more opportunities in rural communities, but she thinks the system also needs work.

“We have to go back to a diversified food system that supports local communities and small farmers,” she said. “Otherwise, we continue on with big ag getting bigger and using local resources to benefit and grow food for other countries, in other states and at the expense of those local communities.”

Contaminated Ground

Amid alarming cancer cases, Martinsville residents rally to keep their water clean, decades after a dry-cleaning business polluted the city’s downtown

published July 7, 2020

Once known as the City of Mineral Water for the healing power of its spring-fed spas, Martinsville, Indiana, now faces the specter of health threats caused by the contamination of its water supply.

For the past 20 years, slow-moving groundwater plumes contaminated with potentially dangerous chemicals have seeped into the city’s municipal well field and drinking water plant. Although the city added carbon filters 15 years ago to clean contaminants from the main plume, the problem is far from resolved.

Now residents are slowly waking up to an understanding of what that contamination might mean for their well-being. They want to know if it has any connection to clusters of rare forms of cancer in the city, in both adults and children.

“When you look at this situation, you know you’re sitting on top of a potential powder keg,” said Tom Wallace, a retired environmental engineer, who worked on the B-1B Strategic Bomber program with Rockwell International and is now chairman of the Morgan County Democratic Party.

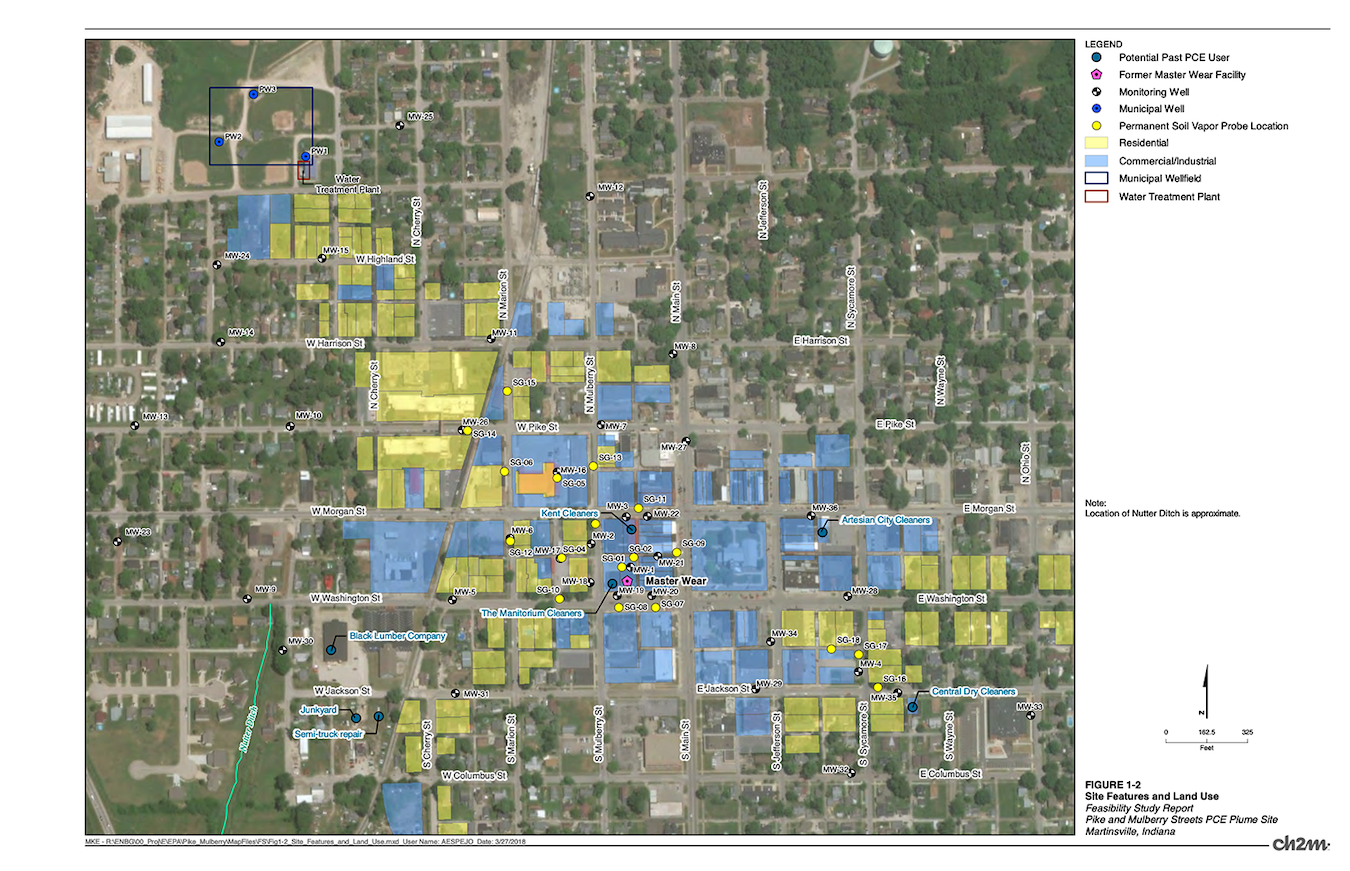

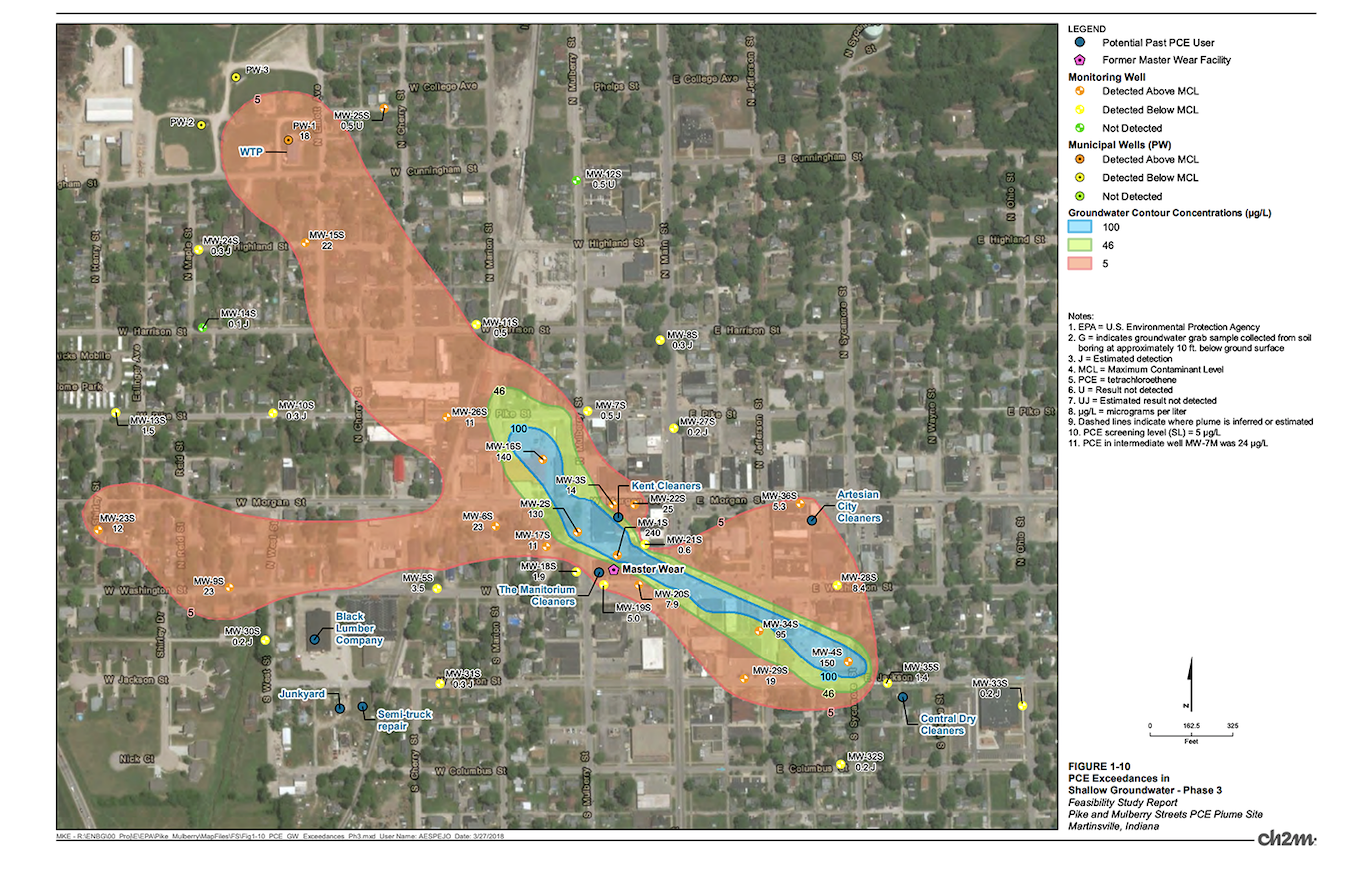

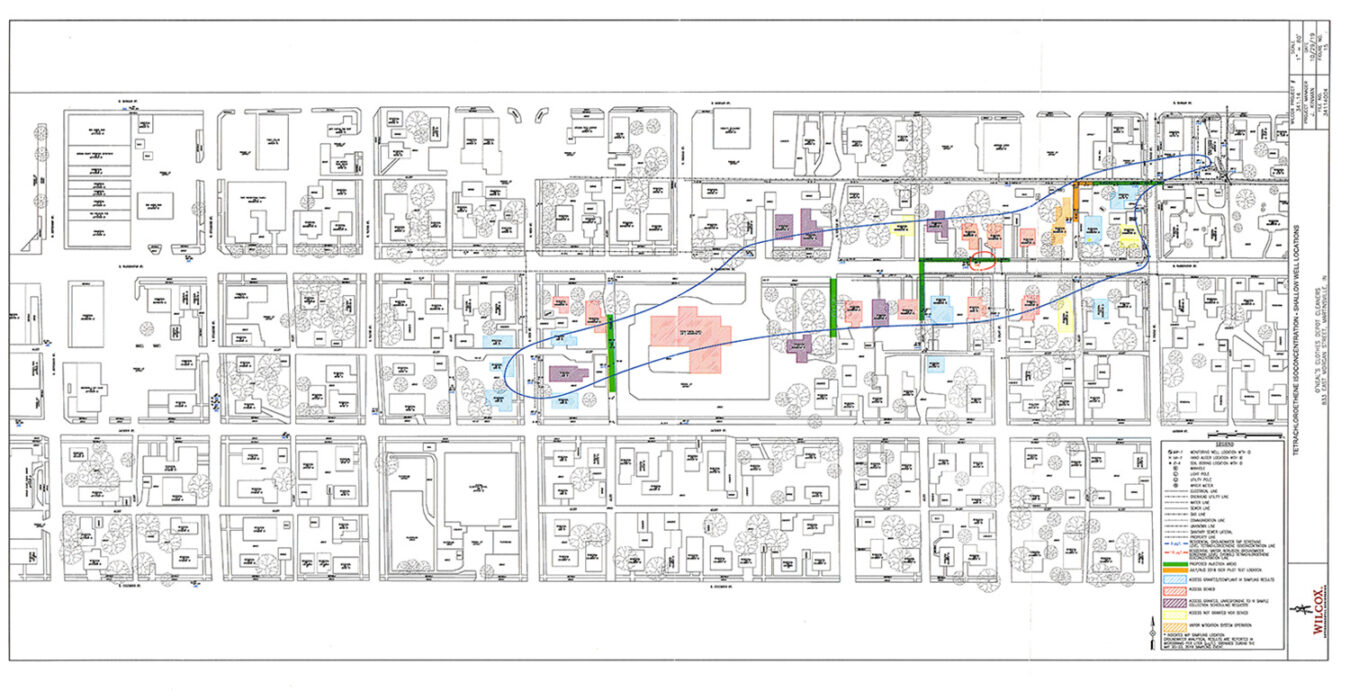

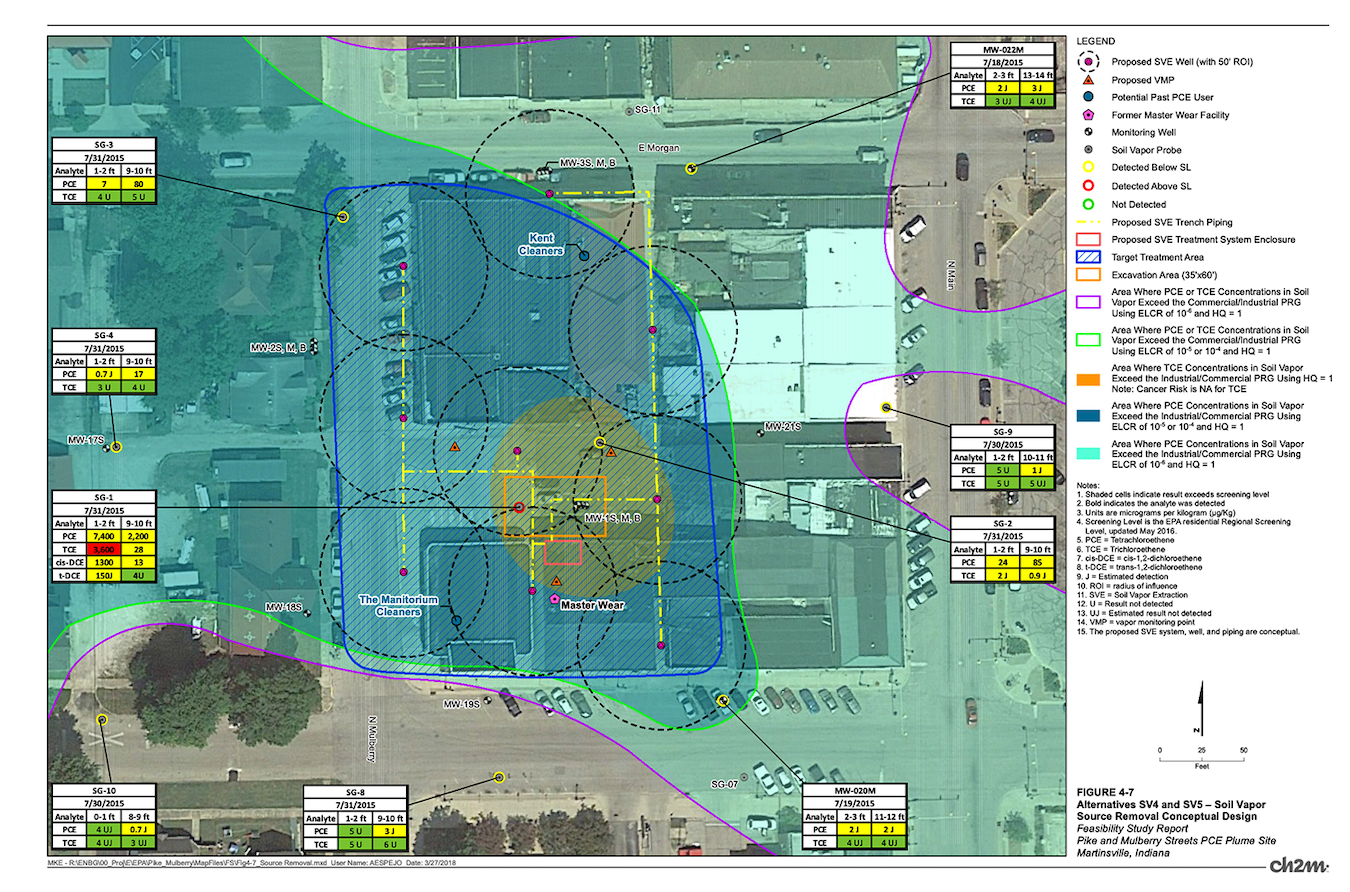

The main 38-acre plume is centered near the intersection of Pike and Mulberry streets in downtown Martinsville and extends to the city’s municipal well field and drinking water plant. It is contaminated with tetrachloroethylene, or PCE, and trichloroethene, or TCE. In 2013, this plume was added to the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Priorities List and designated a Superfund site.

Although the city has been filtering contaminants from the plume for several years to make the water safe for residents, the contamination is increasing, requiring filters to be changed more frequently. In addition to the Superfund site, four more plumes have developed in the town. Only one has been treated.

courtesy of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Wallace is originally from Martinsville and moved back to town around twenty years ago. When he learned about the contamination four years ago, he began to do his own research. He asked questions at city council meetings, set up a Facebook page to share information he gathered and even ran for mayor.

He is concerned not just about health issues, but also about the city’s liability.

In the past year, largely due to Wallace’s efforts, several citizens have come together to participate in health studies, run for local government offices and knock on doors in an effort to get the word out about the site and to effect change that would lead to the cleanup of their town.

“I know what we need to do, and I’ve got to do it a step at a time — put a brick in here, so we have a solid foundation as we go on,” said Wallace, who owns an antique store just off the town square and is also currently running for Indiana State Senator from District 37.

Tom Wallace speaking at an event in February 2020, where results of a pilot health study were discussed with the community of Martinsville.

Martinsville Mayor Kenneth Costin, who took office in January, installed new carbon filters to try to stabilize the well-water system.

“Martinsville’s municipal water is safe to drink, and all testing has concluded that it is,” he said. “The carbonization filtering that we do for removal of the contamination effectively removes the PCE to an undetectable level.”

Costin said the city will continue the carbonization process for all the city’s drinking water even after new wells are in operation, once the city raises money to build them.

But Wallace, who is a community partner for the EPA remedial site cleanup, is concerned that the city isn’t yet meeting the necessary safety standards.

courtesy of the EPA

“This is maybe getting a little picky, but when you look at the EPA, there are two standards,” he said. “There is the public health standard, where the concentration is zero. Then there’s another standard, which is the industry and cost factor standard, and that is what the city is in compliance with.”

Wallace described the industry standard as essentially an efficiency rating for industrial equipment.

“If you went to Walmart and bought an air purifier that says it’s 99 percent efficient, that’s what they are working to, but it has nothing to do with public health,” he said.

A DECADES-LONG PROBLEM

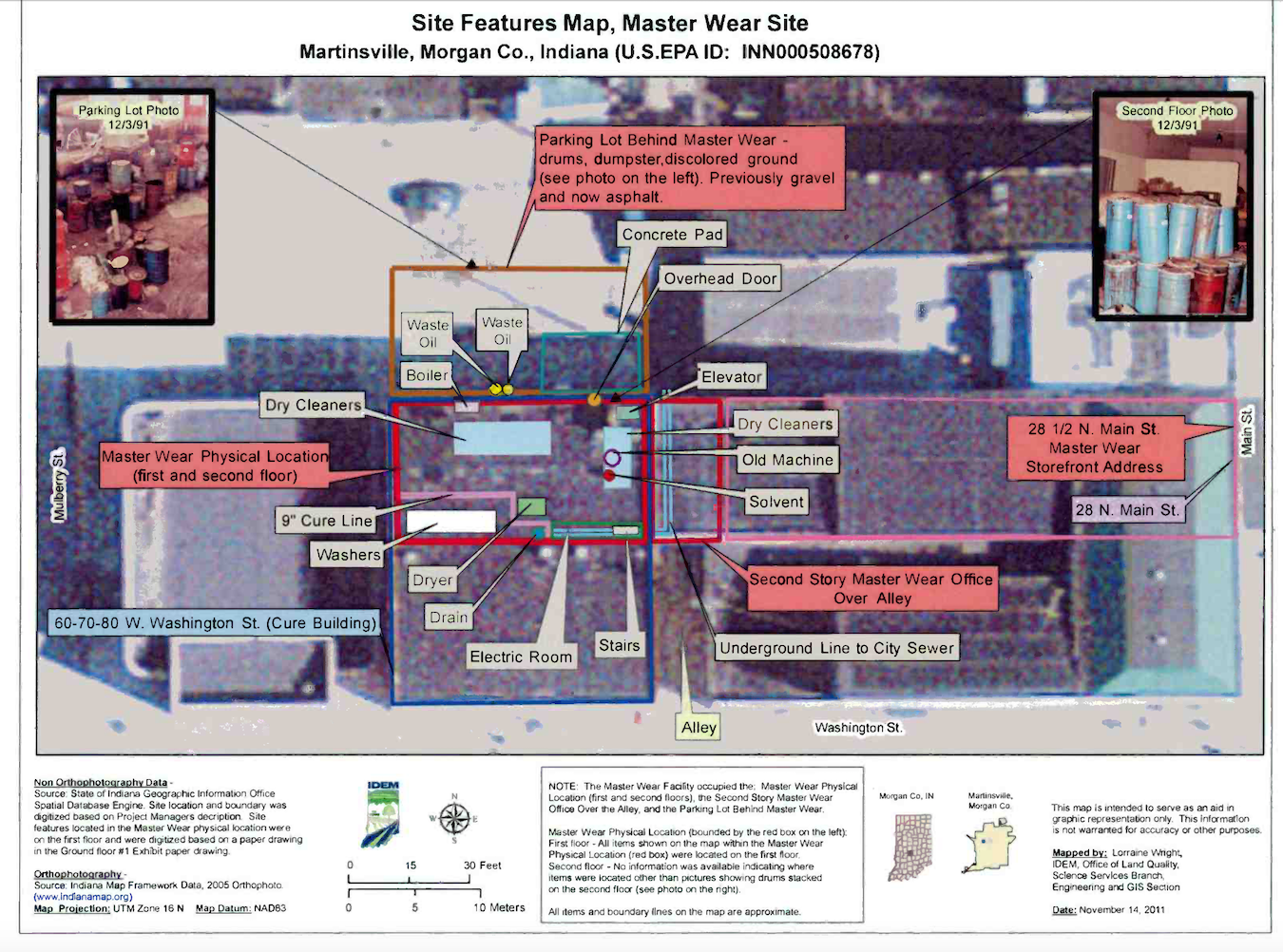

The EPA believes the potential source of the PCE contamination is the former Master Wear dry cleaner that operated from 1986 to 1991 at 28 N. Main St. Multiple complaints of illegal dumping and mishandling of waste drums at the facility were reported to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) from 1987 to 1991.

In 1991, the Martinsville Fire Department responded to a fire at the facility caused by a leak from the chemical processing equipment. The same year, the Martinsville wastewater treatment plant filed two complaints with IDEM against the Master Wear facility, alleging that it was generating more waste product than it was reporting, based on increased water usage. It also alleged Master Wear was discharging oil into the sewer system.

It wasn’t until December 1991, a month after Master Wear closed, that IDEM conducted a complaint investigation under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. The investigation report documented forty-four 55-gallon drums located behind the MasterWear building, with seven labeled as “perchloroethylene.”

courtesy of Indiana Department of Environmental Management

The ground in the area behind the building was described as being discolored with contamination. An additional 86 drums were found unsecured in various parts of the building containing a number of chemicals and waste. The facility is located less than half a mile from the municipal well system.

In 1992, Detrex Corp. removed an additional 275 gallons of perchloroethylene from the site. It wasn’t until 1998 that the last of more than 7,400 gallons was finally removed from the property.

In February 2002, the city first detected PCE in Municipal Well 3. The city has three wells, serving 15,000 residents. By November of the same year, the levels exceeded the EPA Maximum Contaminant Level, or MCL, of five parts per billion.

An EPA map showing levels of PCE within the Superfund site plume

The City of Martinsville asked IDEM to perform a site investigation on the well in late 2002, which took two years to complete, and began activated carbon filtration in 2005.

Between 2003 to 2008, the EPA conducted a time-critical removal action of the Master Wear facility to address contamination in the soil, groundwater and soil vapor. It installed treatment systems that used pressurized air and vacuum methods to remove contaminated gases in the source area.

These systems were shut down in 2008, and by 2010, testing indicated the concentrations of PCE had increased again, including in the municipal well field (before carbon treatment). Due to these high concentrations, the EPA put the site on the National Priorities List in 2013.

Wilcox Environmental Engineering map of the O’Neal Plume in Martinsville

Currently, the only remediation in Martinsville is at the O’Neal plume. The company responsible for the plume, O’Neal’s Clothes Depot Cleaners, is using its insurance to cover remediation by Wilcox Environmental Engineering.

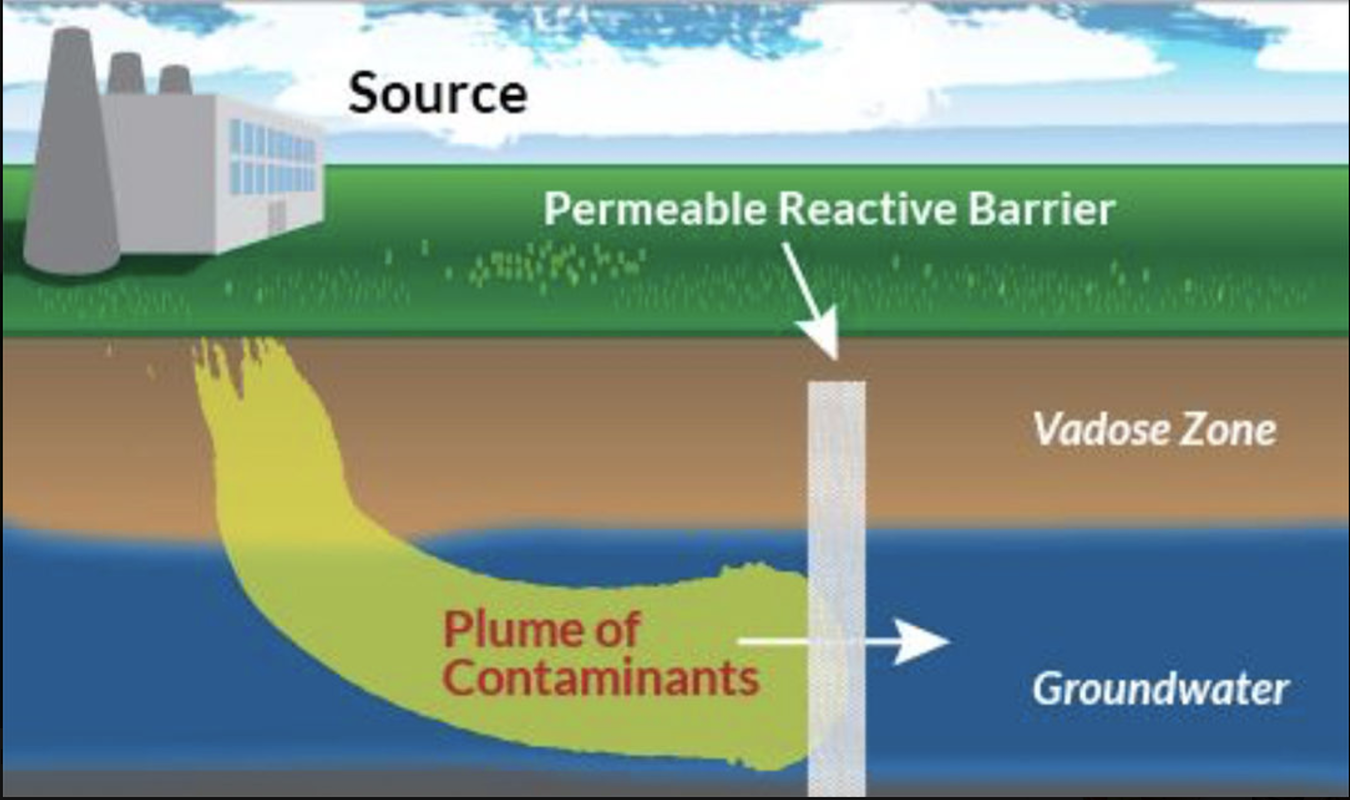

Wilcox is using a product called PlumeStop, which is liquid activated carbon. The product is injected into the ground and forms a permeable barrier that destroys contaminants and allows groundwater to flow through unencumbered.

Illustration of PlumeStop courtesy of Wilcox Environmental Engineering

In February, Jeremy Kinman, the associate technical director of Wilcox, spoke at a community meeting in Martinsville regarding a 2018 pilot test at the O’Neal site that used PlumeStop.

“You will see a drastic and massive drop in PCE concentrations, not in weeks or days or months or years, we’re talking hours. It is immediate,” he said.

Testing at the O’Neal site later this month will reveal whether the treatment has been successful.

“The results of this could be crucial for the planning of the remediation program of the Superfund site and potentially the other three sites within the city limits,” Wallace said. “ The EPA appears to be open to reviewing newer technological methods for remediations, such as is in place at the O’Neal site.”

As Martinsville moves toward remediation of the Pike Street plume, the EPA is lowering cleanup standards for PCE and TCE. In a statement regarding the new draft risk evaluation of TCE, the EPA said it didn’t find an unreasonable risk to the environment under any conditions of use, provided safety directions are followed.

Using the EPA’s Superfund Site Search tool, Indiana Environmental Reporter found more than 1,000 of the EPA’s 1,335 sites on the National Priority List were contaminated with TCE.

According to the EPA, PCE exposure can result in kidney dysfunction, behavioral changes, central nervous system damage and reproductive health damage, including menstrual disorders, altered sperm and birth defects.

The EPA has classified PCE to likely be carcinogenic to humans by all routes of exposure. Studies have shown links between dry-cleaner workers exposed to PCE and bladder cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma.

According to the Indiana State Department of Health, 2018 Cancer Facts and Figures, Morgan County has the highest rate of cancer in the state, adjusted for population.

A STUDY REVEALS HEALTH PROBLEMS

Two years ago, Sa Liu, an environmental health scientist specializing in exposure assessment, moved to Indiana from Berkeley, California, to become an assistant professor in the School of Health Sciences at Purdue University.

Dr. Sa Liu discussing the results of her pilot health study in her office at Purdue University

A colleague suggested she study vapor intrusion, and her research led her to Tom Wallace and to conducting a small-scale health study in Martinsville.

Wallace and Martinsville resident Tim Adams, a retired brigadier general, became the community partners for Liu’s study. Adams has a master’s degree in public health from Harvard University and a Ph.D. in environment/toxicology from Duke University and was the commanding general of the U.S. Army Public Health Command.

The city hired Adams’s company, Adams Public Health Consulting, to work with Wallace and the EPA on the remediation plan.

In December 2019, the research team began collecting information from the homes of twenty volunteers, including samples of tap water, air from inside the home and one component that had not been previously examined.

Dr. Tim Adams was hired by the city of Martinsville to work with Tom Wallace on the Superfund remediation plan.

“What is new for this study that was not previously done before is the third component, that I consider very important, which is to measure people’s internal exposure using biomarkers in the exhaled breath,” Liu said.

Liu said although the initial problem stems from ground water contamination, vapor intrusion into indoor air is a potential exposure pathway, and toxic substances could show up in breath samples.

In February, results from the pilot study were released during an open community meeting, which over 100 people attended. Liu announced that PCE was found in 100 percent of the ten tap water samples taken, and in 60 percent of indoor air samples, with three samples not having a detectable PCE level.

And 100 percent of 39 exhaled breath samples tested positive for PCE.

Liu listens as an audience member asks her a question during a Martinsville community meeting in February.

Liu said the first step after the testing was to compare the preliminary results to known regulatory levels. That’s difficult to do for exhaled breath samples because relevant reference levels don’t exist. High levels of PCE have been found in breath samples from workers in dry-cleaning shops, but that’s not directly comparable.

“What we detected in the individuals living in Martinsville, how this level compares, whether the level indicates any potential health effects or risk, there is no data to support that yet,” Liu said.

Wallace said results of EPA and IDEM testing in Martinsville conducted on private property have not been made public.

“But during the course of that, they did do ambient air studies around town, and we do know that there are spots around town where just walking through, the vapor intrusion is so bad, you’re breathing PCE as you’re walking down the street,” Wallace said.

Liu identified one high PCE concentration in a residence in downtown Martinsville, in the area of the Pike Street plume, where her team conducted indoor air sampling and breath testing.

“It exceeded the action level limits, so we communicated the result with the health department, EPA and IDEM to see what type of actions they would take,” she said.

THE HIGHEST CANCER RATES IN INDIANA

In Indiana, cancer rates released in 2018 stood at about 470 per 100,000 people. In Morgan County, the rate was 537 per 100,000, the highest in the state. The county’s rates of prostate, breast, lung, and colon and rectal cancer all were higher than the state rate, as was its overall mortality rate from cancer.

In addition, six adults in Martinsville have been diagnosed with a rare type of cancer known as gastrointestinal stromal tumor, or GIST. GISTs make up less than 1 percent of gastrointestinal tumors.

According to the National Cancer Institute, the incidence rate of childhood cancer in Morgan County is 17.7 per 100,000 residents. The state average is 18.5 per 100,000. Morgan County is listed as one of the top 25 counties in the state for incidences of childhood cancer, and several cases have emerged that appear to be connected to environmental causes.

In February, it was announced that Martinsville will be taking part in the national Child Health Inventory Resilience Prevention (CHIRP) study. Parents will fill out a fifteen-question online survey about their child’s health, and the results will provide information on the association between chronic childhood diseases and a number of stressors and exposures. The study will help provide a baseline for childhood exposure in Martinsville and allow it to be evaluated against the national average.

One Martinsville resident who has been directly affected by cancer is Deborah Corcoran. On November 10, 2015, her daughter, Sydney, was diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma on her spinal cord. Corcoran was told by her daughter’s neurosurgeon and oncologist the cause was environmental — a gene mutation triggered by chemical exposure.

That night, Corcoran began researching, and at 2:45 a.m., she discovered her house sat on top of two plumes.

“Until I exposed it, no one knew about it,” she said.

Deborah Corcoran’s daughter survived her battle with cancer. Her experience has turned Corcoran into an activist, and she now works tirelessly with Adams and Wallace.

She is now working tirelessly to help Liu, Wallace and Adams with community outreach, research and anything else that is needed, including going door-to-door in the Pike St. plume area to get volunteers signed up for the health study.

“I don’t want anyone else to die from cancer. I don’t want another parent to hear, ‘Your child has cancer.’ That’s the most horrible thing in the world as a parent or your child to have to endure. But if I can help stop this, that’s what I’m going to do,” said Corcoran, whose daughter has since recovered.

Another woman hoping to make a difference is Kathy Thorp, a retired nurse. She is currently running for Morgan County coroner so she would be in a position to keep better track of cancer deaths and, as coroner, she would have the ability to list cause of death due to environmental concerns and conduct an investigation.

Kathy Thorp is currently running for Morgan County coroner and is a volunteer with Hoosier Action, doing community outreach on the EPA Superfund site.

“I feel it’s important. I feel I can make a change,” said Thorp, who is on disability and Medicaid after health problems forced her to retire. “I feel great now, and if it takes something like this for me to get something accomplished, then that’s my mission in life and I want to do that.”

THE FINANCIAL COST

Steps taken to improve water quality in the city have led to increased costs for residents. In 2012, water rates were increased by 40 percent to help pay for carbon filters and a new municipal well-water system, but the filters were never installed. It’s not clear how the rate increase, which would have generated about $6 million from 2012 to 2020, has been used on the water system.

Recently, sewer rates were raised by 69 percent, and the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission approved a 14 percent increase that would be implemented in three phases over the next three years.

“As in nearly every town, the infrastructure continues to naturally erode, and the ongoing replacement of thousands of feet of distribution piping takes place in Martinsville every year with these funds,” said Costin.

Wallace is concerned that the money generated by the 2012 rate increase has not been spent on the water system.

“We are looking at millions of dollars that have been generated, and we have nothing to show for it,” he said.

NOT THE ONLY TOWN?

Wallace has always had a plan. Even when no one was listening or thought he was perhaps being dramatic, he was methodically and patiently working to help not only his community, but others as well.

“When I spoke with Dr. Liu before even beginning the Purdue study, I said, ‘You cannot come in and just do health testing,’” Wallace said. “There is a huge socioeconomic element here. There’s the education factor you have to take into consideration, and if you’re going to have a successful program, you are going to need to factor that in.”

Wallace said social anthropologists also are involved in Liu’s study.

“One of my very first conversations with Purdue about doing this was that we are not the only town like this,” he said. “There are hundreds of them out there, and nobody knows what to do.

Liu and Thorp discuss the results of the Purdue health study in February.

“If we do this right, and we do the proper testing step by step, the proper anthropological and sociological aspects, the environmental justice aspects of it, we will have a nice, concise template that any other city can just pick it up and plug in the pieces. You have this type of contamination, this how we did it, this is how you go ahead and do it for your town.”

Liu and Wallace recently were selected for a $75,000 Showalter Foundation grant to study the effects of low-level, long-term exposure of PCE on children, fetal and childhood development, and neurological impacts.

The money will be awarded July 1, with the study to be completed by July 31, 2021.

Meanwhile, Wallace and Tim Adams have been reviewing the EPA’s draft for final remediation. They said they have an open dialog with the city, with Adams serving as a technical intermediary between the city and the EPA.

Adams is currently writing remediation expectations and procedures that he and Wallace would like to see incorporated in the EPA plan, which would include the PlumeStop technology.

“The EPA plan now is a limited test remediation of approximately two acres, with periodic testing over a five-year period to determine effectiveness of their bio-remediation technology and then expanding to other areas of the Superfund site,” Wallace said. “You are talking about a potential 11- to 34-year duration using their plan, after being subjected to this situation for the last twenty years, that approach was not received well.”

The EPA’s current conceptual design for possible methods of soil vapor removal.

Currently, Wallace and others are working on procuring grants for several other projects, such as testing private well water near the Superfund site and around the town. They want to create a map that lists all of the known cancer cases in town — so far, they have plotted 148 people — to see if there are any similarities between cases. And they want to establish a program for local high schools that would teach students how to do air monitoring and take water and breath samples.

Unlike before, townspeople are actively seeking out Wallace to answer questions about the Superfund site, and word about the Superfund site itself seems to be spreading.

“I went to get breakfast this morning, and a man stopped to ask me about well water. That was an hour conversation,” Wallace said this spring. “I went to get lunch, and the waitress and I had another long discussion. So people are talking.”

The EPA’s final draft remediation proposal for the Pike Street plume is scheduled to be released this summer. A public comment period will follow before the EPA’s final review. Once an order is issued, the EPA will determine funding and oversight of the cleanup.

Realistically, remediation work and cleanup wouldn’t begin for 18 to 24 months at the earliest. Then the process, depending on which cleanup methods are chosen, could take anything from 9 to 34 years to complete.

Wallace said the remediation could offer many green vocational job opportunities to people in

the area, and he is looking for possible training funds.

Keeping momentum and community involvement is important to Wallace, as he stresses this is only the beginning, and people will need to be involved for the duration.

“The biggest element to overcome is the developing culture in this country of willful ignorance by the government and the public,” Wallace said.

“The belief that someone’s cultivated ignorance is as good as any science or technology belies not only common sense, but when viewed at this point in time when the ability to learn, gather information, analyze data, and share is greater than it ever has been, is absurd. There has never been a better time in our history for an educated, informed public, and yet, we are faced with willful efforts to disenfranchise science and maintain a stasis that leads to regression.

“All positive action has to come from the bottom up, from the people in the streets.”

Jobs vs. Health? Controversial Coal-to-Diesel Plant Would Be First in U.S.

published February 13, 2019

Editor’s note: In August 2023, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management notified the developer of the coal-to-diesel plant in Dale, Indiana, that its permit was no longer valid. Mary Hess, a grassroots activist opposing the plant, called Beth Edwards’s story “instrumental” in helping draw attention to the controversy.

DALE, Indiana—Mary Hess sits at her kitchen table wearing a bright yellow “No C2D” shirt, making notes on her laptop, rapidly listing off air emission statistics to the person on the other end of her phone as though she were a scientist, not a retired postal worker.

Hess is preparing for an Indiana Department of Environmental Management listening session regarding the air permit for the proposed Riverview Energy coal-to-diesel, or C2D, plant in Dale, Indiana, about 90 miles south of Bloomington. She’s helping a fellow member of Southwestern Indiana Citizens for Quality of Life fine-tune the statement she would be reading later that night at the Heritage Hills High School in Lincoln City.

“Last night I got to bed before midnight for the first time in a month,” Hess said. “I had just dozed off when somebody in our group had texted me just after 11 p.m. I have gotten texts or phone calls at 2 o’clock in the morning. I keep thinking, ‘Oh, can we coast after this?’ But I know we can’t. We can’t let our guard down.”

The high school auditorium ended up overflowing with 400 people both for and against the proposed plant.

Dale, a town of about 1,500 people in Spencer County, sits along Ind. 231 between Jasper and Lincoln City. It’s a peaceful rural community, where everyone knows and looks out for one another.

Early in summer 2017, rumors started going around town of an industrial plant that might be built. Definitive answers were hard to find, and town board members waited until all the permits for construction were passed before making an announcement on January 25, 2018. Having passed the town’s permit process, Riverview is now waiting for IDEM to release its decision on an air quality permit for the plant before construction can begin.

A “No C2D” sign in a yard in Dale, Indiana.

Since the plant was announced, residents of Dale and the surrounding area have been divided on whether or not it would be good for the community. Along the town’s streets, “No C2D” and “Friends of Coal” signs perch on adjacent lawns.

“It is unfortunate as to the amount of animosity that has risen among friends and neighbors due to differing opinions either in favor or against the plant,” said Kathy Reinke, Spencer County Regional Chamber of Commerce executive director during her statement before the IDEM listening committee. “It seems it’s been more divisive than even when we were dealing with Trump vs. Hillary.”

Kathy Reinke, Spencer County Regional Chamber of Commerce executive director, spoke in favor of the plant at the IDEM listening session on December 5, 2018.

MORE JOBS, HIGHER WAGES?

Coal-to-diesel technology has been around since the 1920s and is currently being used in China, South Africa and Russia. However, if the Dale plant is built, it will be the first time the technology has been used in the U.S.

Coal-to-diesel plants have been proposed before in other states, including South Carolina, Alaska and Kentucky, but all have eventually been canceled. The Dale plant was originally proposed in Vermillion County in 2010. But the project didn’t advance, and Riverview turned instead to Dale, which Merle said is ideally situated because of its access to coal mines, transportation networks, water and natural gas.

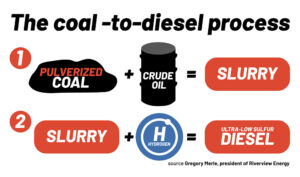

Riverview’s coal-to-diesel process would pulverize coal and mix it with an oil such as crude oil, creating a slurry. Hydrogen, from natural gas, would be added to this slurry, creating ultra-low-sulfur diesel.

Ultra-low-sulfur diesel reduces the amount of airborne sulfur emissions that cause smog, as opposed to regular diesel. It’s also more efficient, meaning heavy machinery could run longer on one gallon of the ultra-low-sulfur diesel than on regular diesel.

Illustration by Alexa Chryssovergis

Riverview Energy president Gregory Merle, a member of the National Coal Council whose family has been in the coal business for six generations, said byproducts of the process would be put to good use. Coal ash would be sold for use in construction rather than stored in potentially hazardous coal ash ponds. And elemental sulfur would be used as an agricultural product.

One of the key reasons many Dale residents support the plant is because they see the potential for higher-paying jobs in the area, both at the plant and also in other sectors.

Indiana coal mines supplying 1.6 to 1.7 million tons of the coal for this plant would put an additional 150 coal miners to work and help offset a 4-million-ton loss of coal due to federal and environmental regulations, according to Indiana Coal Council president Bruce Stevens.

“A coal miner will make $80,000 to $100,000 annually,” Stevens said. “You don’t have those opportunities in a lot of other sectors in that part of the state.”

Boilermaker Timothy Broomfield agreed.

“Right now in the Dale area, there are jobs available, but they pay minimum wage or just above,” he said. “That really isn’t a sustainable amount for a person to raise a family on.”

But Hess is skeptical. She said hiring signs are common in the community, at businesses such as Spencer Industries or Best Chairs, and the unemployment rate is low.

“It doesn’t make sense. We don’t have the people to fill the jobs we’ve got,” she said.

The Riverview plant initially would supply about 2,000 construction jobs, along with 225 permanent jobs including petroleum engineers, maintenance workers and safety monitors.

Mary Hess began Southwestern Indiana Citizens for Quality of Life with other Dale residents who opposed the plant because of health concerns.

People in the community are hopeful these jobs might entice younger people who have left Spencer County to return. However, Hess says that isn’t what she has heard.

“Part of what the development corporation says is they’re bringing this in so kids will stay,” she said. “We are also hearing from millennials who have moved away. The reason they don’t come back to Spencer county is because of the environment. It is more about health of their kids and for their selves.”

HEALTH PROBLEMS A “MATHEMATICAL CERTAINTY”

According to Riverview’s own air permit application, the plant would release around 2.2 million tons of carbon dioxide, 225 tons of carbon monoxide and 120 tons of sulfur dioxide annually.

The proposed site of the plant is within a mile of a nursing home and within two miles of an elementary school.

IDEM reviewed the application, and in its 1,229-page preliminary findings report found it would have “no significant impact on human health.”

Hess doesn’t buy that argument.

“When you consider there is going to be 60 tons of hazardous air pollutants — including carcinogens like benzene, toluene, and hexane released, and you’ve got 2.2 million tons of carbon every year out of this plant — how can that be insignificant?” she said.

The proposed site of the Riverview Energy coal-to-diesel plant in Dale.

Indiana ranks as the sixth worst polluter in the U.S., according to the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory. Rockport, 23 miles south of Dale, ranks 18th out of the 50 worst polluting towns in the country.

During the IDEM hearing in December, 47 people spoke against the plant and seven in favor. However, the audience was equally divided between pro-coal and no-C2D shirts. Residents on both sides were passionate in their comments. IDEM is still reviewing 200 pages of testimony from the hearing, as well as other comments.

“I’m very disappointed I have to be here tonight because that means you all aren’t doing your jobs,” resident Joseph Nickolick told the IDEM authorities at the hearing. “Your job is to protect the environment, not to be the Better Business Bureau. The word ‘management’ in your name says it all. You think you can manage pollution and you can’t. Any pollution is too much. It has a cumulative effect.”

At the IDEM listening session on December 5, 2018, Dale resident Joseph Nickolick spoke against the plant being built, saying IDEM wasn’t doing its job in protecting the environment.

Dr. Norma Kreilein, a pediatrician who has been practicing in southwestern Indiana for 30 years, also spoke at the hearing and said she is already seeing problems in her patients that she attributes to pollution.

“This area is disproportionately burdened already,” she said. “I see a lot of the complications of pregnant mothers’ high blood pressure, delivering early children and delivering sicker children with respiratory issues because of the stress in the womb. Autism and attention deficit disorder, anxiety, stillbirths, just more of everything and more severe than what we should be seeing.”

Dr. Norma Kreilein spoke about the health effects of pollution on children before an IDEM listening committee on December 5, 2018.

In September a study released by the National Academy of Sciences linked lower intelligence to air pollution, especially in boys. Additionally, a previous study from the peer-reviewed journal BMJ Open found that even lower levels of pollution were associated with increases in mental illness in children.

According to the Indiana Department of Education, the state average for students in special education classes is 15 percent. For the 2017-2018 school year, Rockport Elementary had a 28 percent special education rate, Chrisney Elementary School 23 percent, and David Turnham Education Center in Dale 16 percent. Indiana defines special education eligibility to include autism, learning disabilities such as ADHD, and severe anxiety issues.

Kreilein said it’s a mathematical certainty pollution from the Riverview plant will affect the community’s health.

A sign greeting visitors to Spencer County, Indiana.

“Indiana tends to operate by the rule of if the tree falls in the forest and nobody hears it then there’s no sound,” she said. “You know if we don’t monitor and measure, then nobody’s sick, and there’s no impact.”

FINDING A BALANCE

Merle said Riverview is complying with all current environmental regulations.

“We’ve come a very long way in reducing these harmful pollutants that people are afraid of, and regulations are in place,” he said. “There are monitoring requirements, and IDEM and the EPA exist to insure we continue to develop our economy and our society in a way that is not detrimental to our health.”

Riverview President Gregory Merle believed the plant would be a great opportunity not only for Dale, but for the United States as well.

Broomfield said he wants clean air and water for his children, and having read through the IDEM permit, he feels confident in the steps Riverview is taking to ensure compliance.

“I work in these industries, I build the pollution control systems in these industries and I know that we can have good paying jobs and we can have clean air at the same time,” he said.

Steve Hurm, another boilermaker who attended the IDEM hearing, said, “This is what people have been wanting for about 50 years now. This facility uses coal but doesn’t burn coal. And so, when they try to compare it to some of the other facilities around here that are burning coal, it’s apples and oranges. It’s a different type of plant.”

Stevens of the Indiana Coal Council agrees there is a need for health and safety regulations, but said there also needs to be a balance.

“In the previous federal administration, it seemed as though we were getting poked in the eye every day by something new rolling out of one of the federal agencies,” he said. “While the boot of the federal government isn’t on our throat these days, there are many things that were passed that were very onerous to our industry, that we’re still dealing with and having to come to terms with.”

A “Say Yes to C2D” sign in Dale, Indiana.

One of the rules that has hit Indiana coal production the hardest has been the EPA’s Mercury and Air Toxics Standards, which set a national limit on mercury emissions and reduced emissions of sulfur dioxide and fine particles from coal-fired power plants. Some of the older plants in the state decided not to upgrade their systems to meet the new requirements and either shut down the plant or switched to natural gas. This caused a drop in the need for coal within the state.

“I think there are many things that can be generated from coal, not just electricity,” Stevens said. “It just has a bright future if it is given a chance to stand on its own. As one individual told me recently in regard to the Riverview plant, he said, ‘Coal is becoming too valuable to burn.’”

NOT GIVING UP

On January 25, 2019 the Lincolnland Economic Development Corp. held its annual board member luncheon at the Spencer County Youth and Community Center in Chrisney. LEDC president Tom Utter has been spearheading the Riverview plant project in Spencer County.

Tables were set with statuettes of Abraham Lincoln sculpted from coal as centerpieces and coal-shaped chocolates as treats for attendees.

A statuette of Abraham Lincoln sculpted from coal at the Lincolnland Economic Development Corp. annual meeting in 2019.

The main speaker at the event was Riverview president Gregory Merle, as well as Bruce Stevens of the Indiana Coal Council and Terry Seitz, a representative for Indiana Sen. Mike Braun.

“The finalization of this investment in a coal-to-diesel plant marks a significant achievement for both Spencer and Dubois counties,” said Seitz, reading from a statement from Braun. “While on the campaign trail, what I heard repeatedly from coal miners was they wanted someone in Washington that would represent them and their interests. Someone that would keep the industry strong and advocate for them. I intend to be that voice.”

Merle said it was important for him to be present to show gratitude for the community’s support for Riverview.

Members of the Southwestern Indiana Citizens for Quality of Life also attended the luncheon, and after it was over, several members spoke with Merle.